A recent visit to Chartwell, the family home of wartime Prime Minister Winston Churchill (he became Sir Winston, a Knight of the Garter, only in 1953) has left a deep impression on me.

It’s not that I’m unfamiliar with Churchill’s contribution to national life and politics over decades. His life must be one of the most thoroughly documented of any statesman in this country. Not least because of the various memoirs that he wrote, from his early adventures as an army officer in India and South Africa to his long life in politics, and the many biographies penned about him.

At Chartwell, that history becomes tangible. So many personal possessions, awards, and other memorabilia fill the house. There’s a real sense of connection with the great man.

At Chartwell, that history becomes tangible. So many personal possessions, awards, and other memorabilia fill the house. There’s a real sense of connection with the great man.

During his lifetime Churchill attracted his fair share of controversy, and in some respects that has not waned. I’m no apologist for Winston Churchill. What is incontrovertible, however, is the crucial role that he played in securing victory over Nazi Germany during the Second World War. He took the helm of government when the nation demanded decisive leadership. Oh, for such a leader today!

A visit to Chartwell was at the top of the list of National Trust properties during our recent holiday in Kent and East Sussex.

Chartwell lies on the southern outskirts of Westerham in Kent, just five miles west of Sevenoaks (see map).

Chartwell is a rather unprepossessing redbrick house. I’m sure the Churchills did not purchase it (in 1922) for its ‘looks’. More for the views south over the Kent countryside from the terrace (off Lady Churchill’s sitting room on the ground floor), or from the walled garden, which are truly spectacular on a fine day.

However, there was once feature of the house that did catch my attention. From a distance, the columns either side of the front door look like stone. On closer inspection, they are clearly carved from wood.

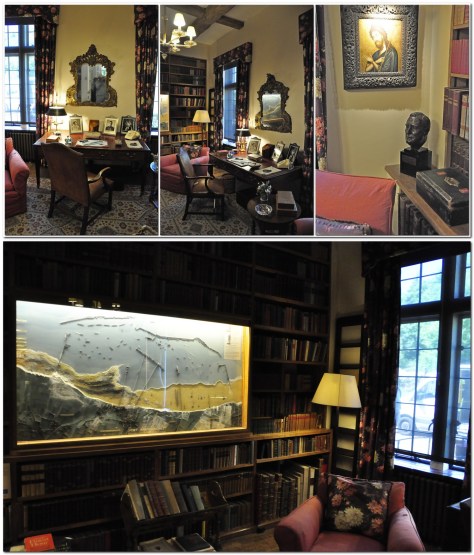

Inside Chartwell, however, is a different matter. This was a family home, and we can see it today more or less as the Churchill family lived there in the 1930s. Lady Churchill and one of her daughters advised the National Trust how the rooms should be presented. Much of the furniture is apparently original to the house.

Inside Chartwell, however, is a different matter. This was a family home, and we can see it today more or less as the Churchill family lived there in the 1930s. Lady Churchill and one of her daughters advised the National Trust how the rooms should be presented. Much of the furniture is apparently original to the house.

On the ground floor, there are three rooms open to the public: Lady Churchill’s Sitting Room; the Drawing Room; and the Library.

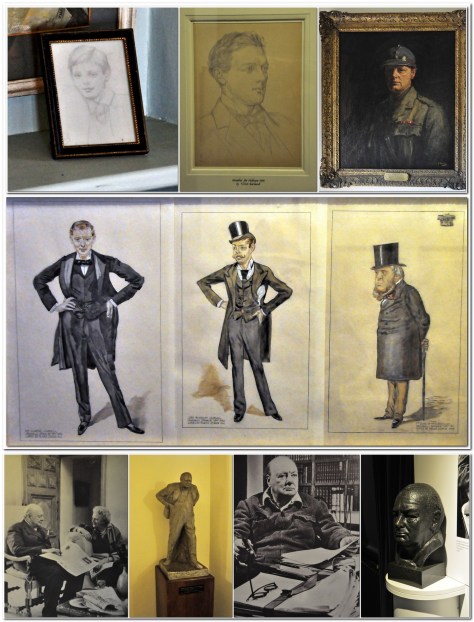

Above the fireplace in Lady Churchill’s Sitting Room is a fine oil painting of her husband of 57 years, one of many paintings and sketches around the house.

Above the fireplace in Lady Churchill’s Sitting Room is a fine oil painting of her husband of 57 years, one of many paintings and sketches around the house.

There’s a door leading out on to the Terrace from this sitting room.

There’s a door leading out on to the Terrace from this sitting room.

The Drawing Room is the ‘jewel’ of Chartwell, and it’s not hard to imagine the Churchills entertaining the great and the good in this room.

Over the fireplace is a painting of Colonist II, the French grey thoroughbred colt that Churchill purchased in 1949 when it won its first race for him, and seventeen more during its twenty-four race career.

Over the fireplace is a painting of Colonist II, the French grey thoroughbred colt that Churchill purchased in 1949 when it won its first race for him, and seventeen more during its twenty-four race career.

On the opposite wall, a 1902 painting, Charing Cross Bridge, by Claude Monet, was gift to Churchill. There is also a large painting of Lady Churchill. On a side table behind the sofa stands a large crystal cockerel (probably made by the famous French glassmaker René Lalique) that was a gift to Lady Churchill from Charles de Gaulle.

Also on the ground floor is the Library (not a large room), with two significant exhibits: a bust of US President Franklin D Roosevelt, and a large model (hanging on the wall) of the Port of Arromanches, one of the artificial harbours that played an important role in the Allied invasion of Europe in 1944.

Moving to the first floor, two rooms, Lady Churchill’s Bedroom and Churchill’s study are open to the public. Two other rooms contain exhibits of the many awards and gifts that Churchill received, and the uniforms he wore.

There are some exquisite Potschappel porcelain figures in the bedroom, but what caught my eye in particular, on a desk at the foot of the bed, are two small framed photographs. One shows his third daughter, and fourth child, Marigold who died in 1921 aged two. The other, equally small photograph is purported to be the last photo taken of Churchill shortly before he died in 1965.

In an Anteroom outside the bedroom there’s a cabinet of Dresden porcelain (one with a portrait of Napoleon, a face seen throughout the house; Churchill was a great admirer of Napoleon), and a wall covered in signed photos. I managed to take photos of two significant figures from the war: General (later Field Marshal) Sir Bernard Montgomery and General Charles de Gaulle.

In an Anteroom outside the bedroom there’s a cabinet of Dresden porcelain (one with a portrait of Napoleon, a face seen throughout the house; Churchill was a great admirer of Napoleon), and a wall covered in signed photos. I managed to take photos of two significant figures from the war: General (later Field Marshal) Sir Bernard Montgomery and General Charles de Gaulle.

In the Museum Room, Churchill’s Nobel Prize for Literature (1953) citation and medal, his Honorary US citizenship, and many, many other awards and gifts, too many to mention individually are on display.

Napoleon sits proudly in the center of Churchill’s desk in the Study. On one side of the room, against the wall, stands a mahogany lectern at which Churchill would work, standing up, dictating to one of his secretaries. He apparently had a small army or researchers helping him with his prodigious literary output. Among the most precious artefacts, hanging from the ceiling, is a Union Jack flag, given to Churchill by Earl Alexander of Tunis, who became Supreme Allied Commander Mediterranean. This flag was hoisted over Rome, the first Allied flag flown over a liberated city in Europe.

Napoleon sits proudly in the center of Churchill’s desk in the Study. On one side of the room, against the wall, stands a mahogany lectern at which Churchill would work, standing up, dictating to one of his secretaries. He apparently had a small army or researchers helping him with his prodigious literary output. Among the most precious artefacts, hanging from the ceiling, is a Union Jack flag, given to Churchill by Earl Alexander of Tunis, who became Supreme Allied Commander Mediterranean. This flag was hoisted over Rome, the first Allied flag flown over a liberated city in Europe.

The Dining Room, on the lower ground floor, overlooking the garden, is simply furnished, with two round tables. Churchill insisted on round tables as they encouraged conversation. I commented to another visitor that we could do with a few more round tables in Parliament these days.

The Dining Room, on the lower ground floor, overlooking the garden, is simply furnished, with two round tables. Churchill insisted on round tables as they encouraged conversation. I commented to another visitor that we could do with a few more round tables in Parliament these days.

There is also a painting of William Ewart Berry, Viscount Camrose. Why?

In July 1945, even before the war with Japan had ended victoriously for the Allies, a General Election was held in the UK. Churchill was booted out of office. Extraordinary really, considering the experiences of the previous five years. Worse still for Churchill personally was that he was bankrupt. And to sort his financial predicament he was faced with selling his beloved Chartwell. That’s when an anonymous group of seventeen wealthy individuals¹, headed by Lord Camrose, came to the rescue, and purchased Chartwell for the nation, with the proviso that the Churchills could live there as long as they wished. The names of these benefactors were eventually published in a newspaper; there’s also a plaque with their names at Chartwell.

The National Trust took over Chartwell in 1946/47

Churchill’s studio just below the house is full of many of his oil paintings. This became a serious hobby, and after leaving office in 1945 he thought of selling up and moving to the south of France, and paint all day long.

Many of his paintings that line the studio walls depict Mediterranean scenes.

The gardens and grounds are extensive.

Another of Churchill’s hobbies was brick laying, and he constructed part of one of the walls of the Walled Garden near the Studio.

From the terrace at the top of the Walled Garden is one of the best viewpoints in the whole of Chartwell.

We had arrived to Chartwell just after the café opened at 10 am, and enjoyed a welcome cup of coffee before exploring the gardens. Entry to the house itself is by timed ticket. We opted for the 11 am entry. This system ensures that, with a normal flow of visitors through the house, nowhere becomes particularly congested.

I was amazed that photography was permitted throughout the house and studio. Please look at the more extensive album of photos that I took.

Chartwell had long been on my bucket-list since I read (about 15 years ago or so) an excellent biography of Churchill by Roy Jenkins. Mission accomplished!

Chartwell had long been on my bucket-list since I read (about 15 years ago or so) an excellent biography of Churchill by Roy Jenkins. Mission accomplished!

The visit to Chartwell was undoubtedly the highlight of our holiday in East Sussex and Kent. The NT staff and volunteers were very welcoming—as always—and knowledgeable. Always ready and keen to answer any question, however mundane. They make each visit so much more interesting and worthwhile.

Quebec House in Westerham

After we left Chartwell, en route to Ightham Mote, we stopped briefly at Quebec House in the village of Westerham, less than two miles north from Chartwell.

Quebec House was the childhood home (then known as ‘Spiers’) of General James Wolfe, victor of the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, also known as the Battle of Quebec in 1759 in which he lost his life. It was a major turning point in the Seven Years’ War.

Quebec House was closed unfortunately, but we did manage to wander around the exterior and take in the splendour of this 16th century town house. Its current look dates from the mid-1600s.

¹Lord Camrose

Lord Bearstead

Lord Bicester

Sir James Caird

Sir Hugo Cunkiffe-Owen

Lord Catto

Lord Glendyne

Lord Kenilworth

Lord Leathers

Sir James Lithgow

Sir Edward Mountain

Lord Nuffield

Sir Edward Peacock

Lord Portal

J. Arthur Rank

James de Rothschild

Sir Frank Stewart

Loved this! Thanks for sharing…have you been to Hyde Park–FDR’s family home on the Hudson River? A favorite of mine…

LikeLike

Hi Denise – no, I haven’t. We’re traveling along part of the Hudson later this year, but probably won’t have time for that visit.

LikeLike

Actually, I just looked where it was and we are staying one night in Poughkeepsie, less than 5 km away. Given the itinerary I have planned still not sure if we could fit this in.

LikeLike