The weather during June and July was appalling, very wet and cool. However, summer returned temporarily mid-July so we grabbed that rare opportunity to visit two castles in North Yorkshire, around 62 miles south from home.

Richmond Castle (founded in the 1070s) and 12th century Middleham Castle (just 10 miles south of Richmond) in Swaledale and Wensleydale respectively, are among the most important castles in the north of England, perhaps in the country as a whole. They simply exude history! The former was at the heart of one of the largest post-Norman Conquest estates; the other was the boyhood home and later power base of one of England’s most notorious kings.

I have to admit to being a little disappointed initially with Richmond Castle. Until viewed from the south (which we did as we headed to Middleham, but could not stop because of parking restrictions), it’s not easy at ground level to appreciate just how magnificent it must have been in its heyday.

Richmond Castle from the south, with the residential accommodation on the right, and the later Keep behind.

Richmond Castle from the air, clearly showing the size of the enclosure which must have been full of other ‘temporary’ buildings when the castle was originally occupied. The residential accommodation is in the top right corner, with the Cockpit Garden beyond.

The original castle was built by Alan Rufus (a cousin of William I, the Conqueror) after 1071 but it wasn’t until the 12th century that the magnificent Keep was added.

An artist’s impression of how the castle must have looked not longer after its foundation in the late 11th century.

By the middle of the 16th century the castle had become derelict, but was revived centuries later and a barracks was built along the western wall in the 19th century, as well as a cell block adjoining the keep. In fact the castle was occupied during the Great War (1914-18) and housed conscientious objectors, with some kept as prisoners in the cell block.

I’m not going to describe in detail the history of Richmond Castle here. There is much more information on the English Heritage website, where you can also find a detailed site plan.

From the roof of the Keep there are magnificent views over the castle enclosure and to all points of the compass around Swaledale and the town of Richmond itself. The castle stands to one side of the market place.

The residential block (Scolland’s Hall), on the southeast corner of the enclosure is contemporaneous with the late 11th century curtain wall, but service buildings were added around 1300.

To the east of this area lies the Cockpit Garden (mainly yew shrubs and lawn) surrounded by walls built in the 12th century and some of uncertain age. English Heritage has developed an ornamental section on the north side.

On the eastern wall there is a small chapel, dedicated to St Nicholas and dating from the late 11th century.

The 19th century barracks block has long since been demolished, but a cell block adjoining the Keep, also from the 19th century still stands, and via steps on to its roof provide easier access to the first floor of the Keep rather than the very narrow and steep spiral staircase in the southwest corner of the ground floor.

There is an excellent exhibition on the floor above the visitor entrance and shop. I wish I’d taken more time to look at the various posters, especially those dealing with the incarceration of conscientious objectors in WW1. Read all about their fate on the English Heritage website.

But we’d already decided to move on to Middleham Castle, and having enjoyed a picnic lunch beside the River Swale (reportedly one of the fastest-flowing rivers in England), that’s precisely what we did, crossing over the bridge that replaced an original medieval one.

Middleham Castle is much more impressive, and it’s remarkable how much has survived the ravages of the centuries.

Middleham Castle from the southwest, probably from the site of William’s Hill where an original fortification was constructed shortly after the Norman Conquest.

From the moment you walk through the impressive gatehouse, it’s impossible to ignore the grandeur of this castle, which was more a palatial residence than a fortification.

Close by the castle are the remains of an early castle, probably constructed after the Norman Conquest in 1066. Known as William’s Hill, it can easily be seen from the top of Middleham’s south-east turret as the cluster of trees on the skyline in the image below.

Construction of the stone castle began in the later 12th century, and was extended over several centuries. In 1260, the castle passed into the Neville family, one of the most powerful in the kingdom. Richard Neville (1428-1471), the 16th Earl of Warwick and 6th Earl of Salisbury came to be known as ‘Warwick the Kingmaker’ given the power and influence he wielded.

Middleham’s central keep was one of the largest of any castle in the country, and the oldest part of the castle. There are extensive basements with kitchens, above which were the main hall and family apartments. Surrounding the keep is a curtain wall, with several towers, only one of which is round, the Prince’s Tower on the southwest corner.

English Heritage has a detailed ground plan of the castle on its website. There is also a comprehensive historical account here and illustrations of how the castle must have looked in its heyday. It certainly has the feel of a family residence, a show of wealth and opulence. One feature that English Heritage highlights in its introduction and on ground plan is the large number of latrines, with some dedicated latrine towers. It seems that no-one was ever caught short at Middleham.

The original entrance to the castle was on the east side, but this was changed around 1400 to a gatehouse on the north wall. The entrance to the keep is via a modern stairway to the first floor. As I ascended those stairs I imagined what it must have been like all those centuries ago as guests arrived at the castle and were escorted to their rooms. And ascending to the top of the south-east turret gives a wonderful view over the ruins and the wider landscape of Wensleydale.

Surrounding the central keep on the north, west and south sides, are a series of chambers that must have once been accommodation for staff.

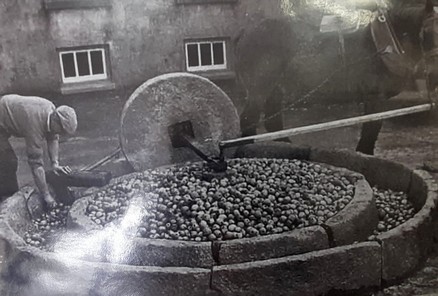

One interesting feature inside the south wall is a large circular ‘trough’, and a raised circular platform next to it. While the left hand feature in the image below is described as ‘ovens’ on the ground plan, there is no description for the trough.

The ovens and ‘trough’ from the south-east turret.

Both date from the 16th century when, apparently, the local folk were allowed into the castle to use the ovens and the trough. I had to ask, and the best guess is that the trough was a cider press, perhaps as shown in this illustration.

Richard, Duke of Gloucester (1452-1485) was the youngest brother of Edward IV, who spent his boyhood at Middleham (along his elder brother George, who was created Duke of Clarence). The Kingmaker’s two daughters Isabel and Anne grew up at Middleham. Isabel married Clarence, and Anne married Gloucester.

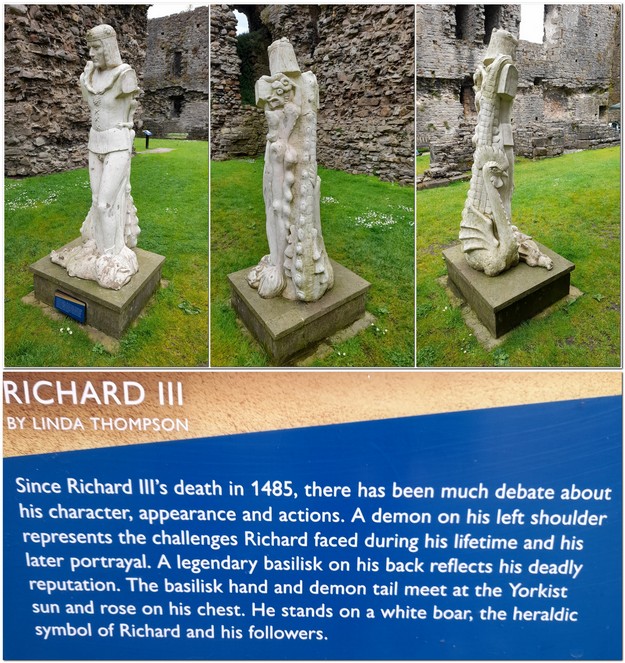

Middleham became Gloucester’s northern stronghold, a base from which to gain power and eventually the crown, becoming King Richard III in June 1483. There is a commemorative statue of Richard just inside the castle.

He was defeated by Henry Tudor (who would become King Henry VII) at the Battle of Bosworth Field (the last significant battle of the Wars of the Roses) in August 1485, where he was killed. And disappeared from history so to speak until his body was discovered beneath a car park in Leicester in 2012-13.

Two castles in one day. Being just a few miles apart it was an easy excursion for us from North Tyneside, and well worth the journey south. A highly recommended day out!

Neither castle has dedicated parking. In Richmond we chose the Fosse Car Park just below the castle. I think it was £3 for 4 hours. There is parking available in the Market Place beside the castle, but I believe it’s more time limited. In Middleham, we parked in Back Street just outside the castle, where there was space for just a handful of vehicles. Parking would be trickier, I guess, on a busier day.

Photo album for Richmond Castle

Photo album for Middleham Castle

of Scotland (right) who was Henry’s brother-in-law, had crossed the border with an army of some 30,000 aiming to draw Henry’s troops northwards, thereby cementing his commitment to the

of Scotland (right) who was Henry’s brother-in-law, had crossed the border with an army of some 30,000 aiming to draw Henry’s troops northwards, thereby cementing his commitment to the