As you exit the Tyne Tunnel south on the A19, there’s a road sign on the right, pointing left  towards South Shields, Jarrow, and Hebburn on the A185, and a brown sign for Jarrow Hall and St Paul’s, with the English Heritage logo (right) prominently displayed. A road we’d not been down until last week.

towards South Shields, Jarrow, and Hebburn on the A185, and a brown sign for Jarrow Hall and St Paul’s, with the English Heritage logo (right) prominently displayed. A road we’d not been down until last week.

St Paul’s is a part-Saxon church and ruins of a Saxon-medieval monastery, dating from the 7th century, which surely must be one of the most significant sites for early English Christianity. It has been an active site of worship for over 1300 years.

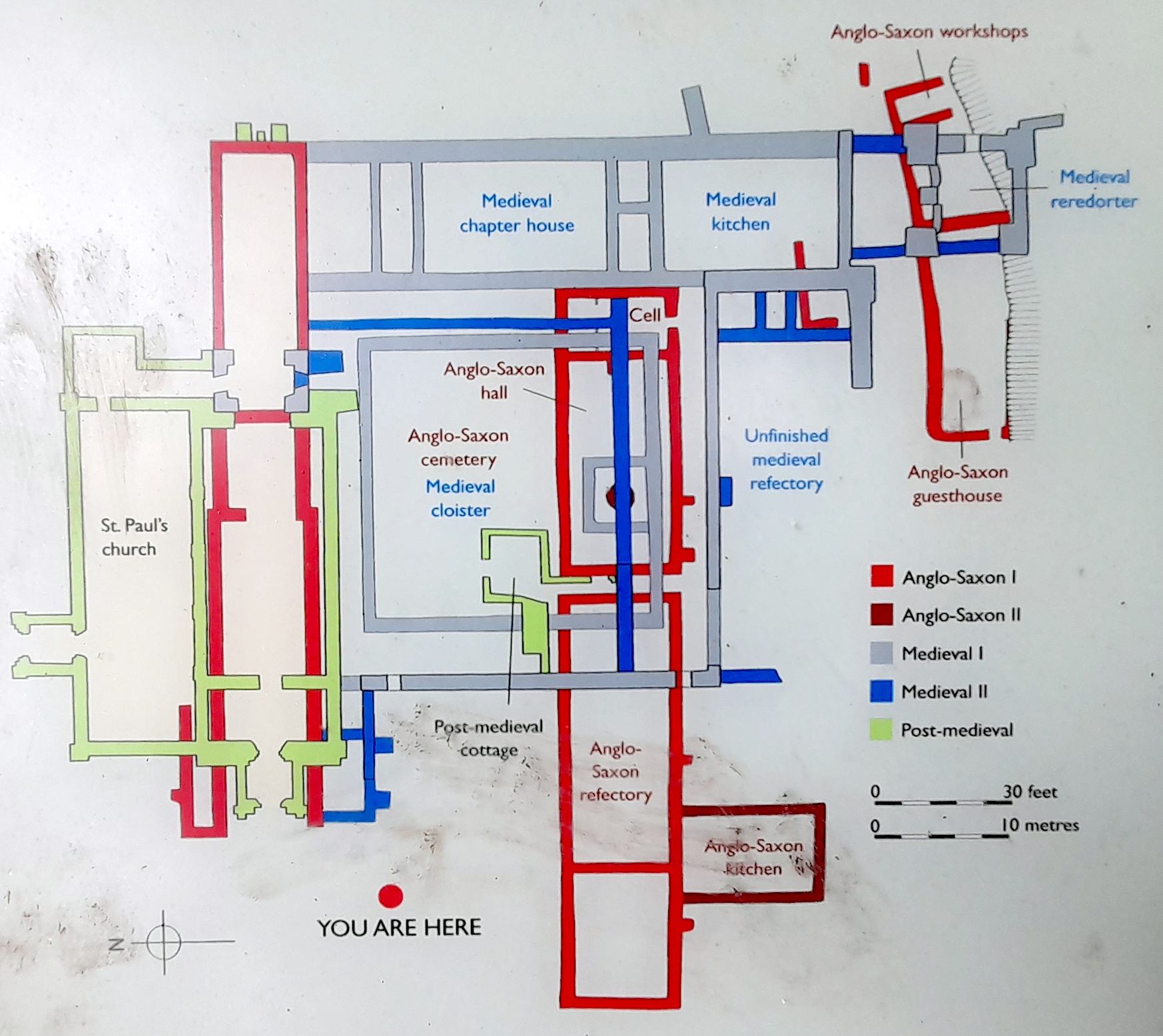

The site was excavated by the late Professor Dame Rosemary Cramp of Durham University (who died in April this year) between 1963 and 1978. Today, flat stones mark out the Anglo-Saxon monastery, and cobbles the later medieval buildings.

The church and monastery were built on land given by King Ecgfrith of Northumbria in AD 681, beside the River Don, on the south bank of the River Tyne, into which it flows (map). The community was founded by Benedict Biscop (right) an Anglo-Saxon abbot from a noble Northumbrian family, who had also founded—seven years earlier—St Paul’s twin, St Peter’s (below) on the north bank of the River Wear at Monkwearmouth (map).

The church and monastery were built on land given by King Ecgfrith of Northumbria in AD 681, beside the River Don, on the south bank of the River Tyne, into which it flows (map). The community was founded by Benedict Biscop (right) an Anglo-Saxon abbot from a noble Northumbrian family, who had also founded—seven years earlier—St Paul’s twin, St Peter’s (below) on the north bank of the River Wear at Monkwearmouth (map).

Steph and I had first come across the name of Benedict Biscop when we visited the National Glass Centre in Sunderland in November 2022. In AD 674 Biscop had sought help from craftsmen from Gaul to make windows for St Peter’s, which is close by the glass center.

So why is St Paul’s so significant? Having entered the monastic life, aged seven, at Monkwearmouth around AD 680, and transferring later to St Paul’s at Jarrow, their most famous resident was Saint Bede (often known as the Venerable Bede). Although traveling to other ecclesiastical communities around the country, Bede essentially spent his life at Jarrow, and died there around AD 735. He is now buried in Durham Cathedral.

Portrait of Bede writing, from a 12th-century copy of his Life of St Cuthbert (British Library, Yates Thompson MS 26, f. 2r).

Bede is considered one of the most important teachers and writers of the early medieval period, his most famous work being Ecclesiastical History of the English People written about AD 731. In 1899, Pope Leo XIII declared him a Doctor of the Church, a rare accolade indeed.

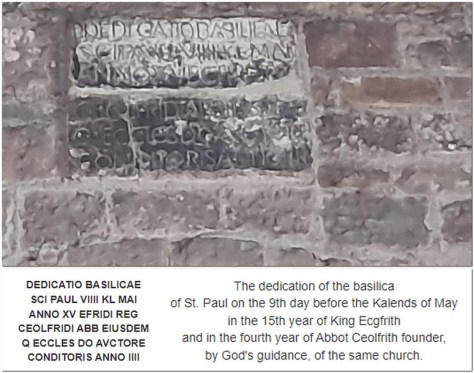

So what is there to see at Jarrow¹? St Paul’s was dedicated on 23 April 685, but the only surviving Saxon section is the chancel.

The Victorian north door, with west door (and main entrance today) on the right.

The rest was added or refurbished by the Victorian architect Sir George Gilbert Scott in the 1860s. In the nave of the church the foundations of the original church can also be seen in a window placed in the floor.

The Anglo-Saxon chancel on the right. A belfry was added in the 12th century.

Click on the image below to open a larger version.

The dedication stones can be seen above the arch leading into the chancel which is the only surviving section of the original Saxon church.

The ruins alongside the church are quite extensive and date mostly from the 11th century. And, like all other ecclesiastical communities it suffered during the Dissolution of the Monasteries during the reign of Henry VIII. Here is a selection of some of the photos I took during our visit. I have put all of them (including images of the English Heritage information boards) in this photo album.

Northumbria was certainly a cradle of Christianity in England. To the south of St Paul’s and St Peter’s stand Finchale Priory and Durham Cathedral on the banks of the River Wear. North and northeast in the heart of the Northumberland landscape stand at least two medieval chapels at Edlingham (dedicated to St John the Baptist) and Heavenfield (dedicated to St Oswald), and the early Christian pilgrimage site of Lady’s Well, Holystone.

¹ I must take this opportunity to recognise the very friendly and knowledgeable volunteers inside St Paul’s who made us feel most welcome.