Imagine a little corner of Birmingham, just a couple of miles southwest of the city center. Edgbaston, B15 to be precise. The campus of The University of Birmingham; actually Winterbourne Gardens that were for many decades managed as the botanic garden of the Department of Botany / Plant Biology.

As a graduate student there in the early 1970s I was assigned laboratory space at Winterbourne, and grew experimental plants in the greenhouses and field. Then for a decade from 1981, I taught in the same department, and for a short while had an office at Winterbourne. And for several years continued to teach graduate students there about the conservation and use of plant genetic resources, the very reason why I had ended up in Birmingham originally in September 1970.

Potatoes at Birmingham

It was at Birmingham that I first became involved with potatoes, a crop I researched for the next 20 years, completing my PhD (as did many others) under the supervision of Professor Jack Hawkes, a world-renowned expert on the genetic resources and taxonomy of the various cultivated potatoes and related wild species from the Americas. Jack began his potato career in 1939, joining Empire Potato Collecting Expedition to South America, led by Edward Balls. Jack recounted his memories of that expedition in Hunting the Wild Potato in the South American Andes, published in 2003.

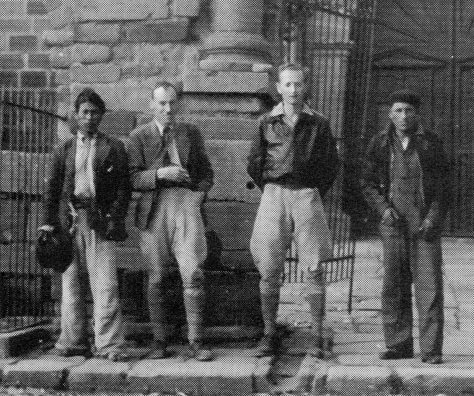

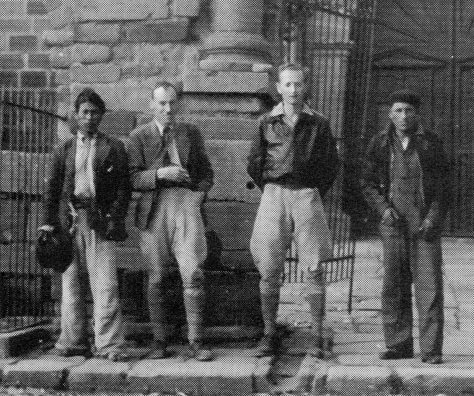

29 March 1939: Bolivia, dept. La Paz, near Lake Titicaca, Tiahuanaco. L to R: boy, Edward Balls, Jack Hawkes, driver.

The origins of the Commonwealth Potato Collection

Returning to Cambridge, just as the Second World War broke out, Jack completed his PhD under the renowned potato breeder Sir Redcliffe Salaman, who had established the Potato Virus Research Institute, where the Empire Potato Collection was set up, and after its transfer to the John Innes Centre in Hertfordshire, it became the Commonwealth Potato Collection (CPC) under the management of institute director Kenneth S Dodds (who published several keys papers on the genetics of potatoes).

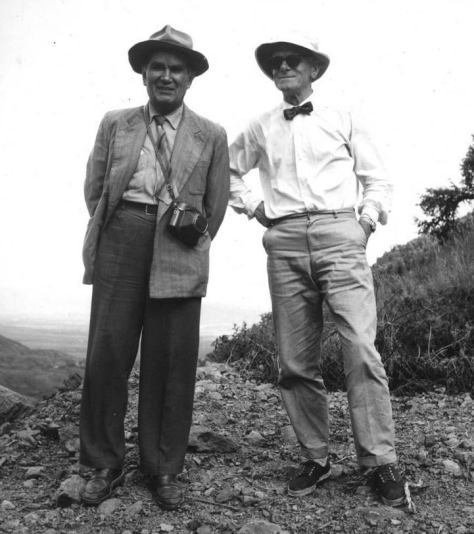

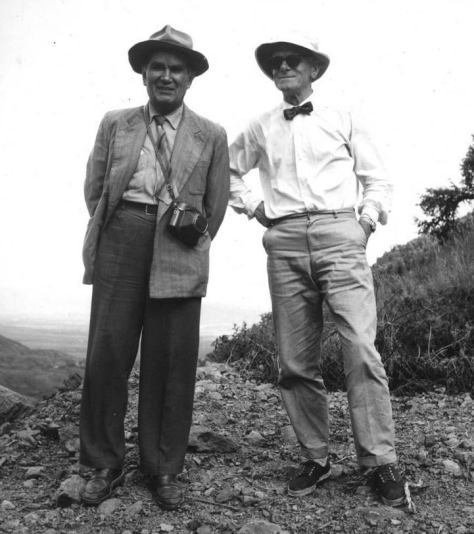

Bolivian botanist Prof Martin Cardenas (left) and Kenneth Dodds (right). Jack Hawkes named the diploid potato Solanum cardenasii after his good friend Martin Cardenas. It is now regarded simply as a form of the cultivated species S. phureja.

Hawkes’ taxonomic studies led to revisions of the tuber-bearing Solanums, first in 1963 and in a later book published in 1990 almost a decade after he had retired. You can see my battered copy of the 1963 publication below.

Dalton Glendinning

The CPC was transferred to the Scottish Plant Breeding Station (SPBS) at Pentlandfield just south of Edinburgh in the 1960s under the direction of Professor Norman Simmonds (who examined my MSc thesis). In the early 1970s the CPC was managed by Dalton Glendinning, and between November 1972 and July 1973 my wife Steph was a research assistant with the CPC at Pentlandfield. When the SPBS merged with the Scottish Horticultural Research Institute in 1981 to form the Scottish Crops Research Institute (SCRI) the CPC moved to Invergowrie, just west of Dundee on Tayside. The CPC is still held at Invergowrie, but now under the auspices of the James Hutton Institute following the merger in 2011 of SCRI with Aberdeen’s Macaulay Land Use Research Institute.

Today, the CPC is one of the most important and active genetic resources collections in the UK. In importance, it stands alongside the United States Potato Genebank at Sturgeon Bay in Wisconsin, and the International Potato Center (CIP) in Peru, where I worked for more than eight years from January 1973.

Hawkes continued in retirement to visit the CPC (and Sturgeon Bay) to lend his expertise for the identification of wild potato species. His 1990 revision is the taxonomy still used at the CPC.

So what has this got to do with the EU?

For more than a decade after the UK joined the EU (EEC as it was then in 1973) until that late 1980s, that corner of Birmingham was effectively outside the EU with regard to some plant quarantine regulations. In order to continue studying potatoes from living plants, Jack Hawkes was given permission by the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (MAFF, now DEFRA) to import potatoes—as botanical or true seeds (TPS)—from South America, without them passing through a centralised quarantine facility in the UK. However, the plants had to be raised in a specially-designated greenhouse, with limited personnel access, and subject to unannounced inspections. In granting permission to grow these potatoes in Birmingham, in the heart of a major industrial conurbation, MAFF officials deemed the risk very slight indeed that any nasty diseases (mainly viruses) that potato seeds might harbour would escape into the environment, and contaminate commercial potato fields.

Jack retired in 1982, and I took up the potato research baton, so to speak, having been appointed lecturer in the Department of Plant Biology at Birmingham after leaving CIP in April 1981. One of my research projects, funded quite handsomely—by 1980s standards—by the Overseas Development Administration (now the Department for International Development, DFID) in 1984, investigated the potential of growing potatoes from TPS developed through single seed descent in diploid potatoes (that have 24 chromosomes compared with the 48 of the commercial varieties we buy in the supermarket). To cut a long story short, we were not able to establish this project at Winterbourne, even though there was space. That was because of the quarantine restrictions related to the wild species collections were held and were growing on a regular basis. So we reached an agreement with the Plant Breeding Institute (PBI) at Trumpington, Cambridge to set up the project there, building a very fine glasshouse for our work.

Then Margaret Thatcher’s government intervened! In 1987, the PBI was sold to Unilever plc, although the basic research on cytogenetics, molecular genetics, and plant pathology were not privatised, but transferred to the John Innes Centre in Norwich. Consequently our TPS project had to vacate the Cambridge site. But to where could it go, as ODA had agreed a second three-year phase? The only solution was to bring it back to Birmingham, but that meant divesting ourselves of the Hawkes collection. And that is what we did. However, we didn’t just put the seed packets in the incinerator. I contacted the folks at the CPC and asked them if they would accept the Hawkes collection. Which is exactly what happened, and this valuable germplasm found a worthy home in Scotland.

In any case, I had not been able to secure any research funds to work with the Hawkes collection, although I did supervise some MSc dissertations looking at resistance to potato cyst nematode in Bolivian wild species. And Jack and I published an important paper together on the taxonomy and evolution of potatoes based on our biosystematics research.

A dynamic germplasm collection

It really is gratifying to see a collection like the CPC being actively worked on by geneticists and breeders. Especially as I do have sort of a connection with the collection. It currently comprises about 1500 accessions of 80 wild and cultivated species.

Glasshouse for the CPC at the JHI

Solanum neorossii, 2n=2x=24, from Argentina

Solanum neorossii

Solanum schenckii , 2n=6x=72, from Mexico

Solanum pinnatisectum, 2n=2x=24, from Mexico

Solanum lignicaule, 2n=2x=24, from southern Peru

Solanum jamesii, 2n=2x=24, from Mexico and southern USA

Solanum circaeifolium, 2n=2x=24, from cloud forest in Bolivia

Solanum brevicaule, 2n=2x=24, from Bolivia

Solanum acaule, 2n=4x=48, a high altitude species found in Peru, Bolivia and Argentina

Solanum lignicaule, 2n=2x=24

Sources of resistance to potato cyst nematode in wild potatoes, particularly Solanum vernei from Argentina, have been transferred into commercial varieties and made a major impact in potato agriculture in this country.

Safeguarded at Svalbard

Just a couple of weeks ago, seed samples of the CPC were sent to the Svalbard Global Seed Vault (SGSV) for long-term conservation. CPC manager Gaynor McKenzie (in red) and CPC staff Jane Robertson made the long trek north to carry the precious potato seeds to the vault.

Jane Robertson and Gaynor McKenzie

Potato reproduces vegetatively through tubers, but also sexually and produces berries like small tomatoes – although they always remain green and are very bitter, non-edible.

Tubers of farmer varieties from Peru

Berries of Solanum brachycarpum, 2n=6x=72, from Mexico

We rarely see berries after flowering on potatoes in this country. But they are commonly formed on wild potatoes and the varieties cultivated by farmers throughout the Andes. Just to give an indication of just how prolific they are let me recount a small piece of research that one of my former colleagues carried out at CIP in the 1970s. Noting that many cultivated varieties produced an abundance of berries, he was interested to know if tuber yields could be increased if flowers were removed from potato plants before they formed berries. Using the Peruvian variety Renacimiento (which means rebirth) he showed that yields did indeed increase in plots where the flowers were removed. In contrast, potatoes that developed berries produced the equivalent of 20 tons of berries per hectare! Some fertility. And we can take advantage of that fertility to breed new varieties by transferring genes between different strains, but also storing them at low temperature for long-term conservation in genebanks like Svalbard. It’s not possible to store tubers at low temperature.

Here are a few more photos from the deposit of the CPC in the SGSV.

Waiting to go inside the vault

With SGSV manager Åsmund Asdal

CPC boxes safely on the shelves

I am grateful to the James Hutton Institute for permission to use these photos in my blog, and many of the other potato photographs displayed in this post.

Rice is such a fascinating crop you might want to understand a little more. And there’s no better source than Rice Today, a magazine launched by the

Rice is such a fascinating crop you might want to understand a little more. And there’s no better source than Rice Today, a magazine launched by the