A billion lives, it is said.

Official portrait of Norman Borlaug for his Nobel Peace Prize.

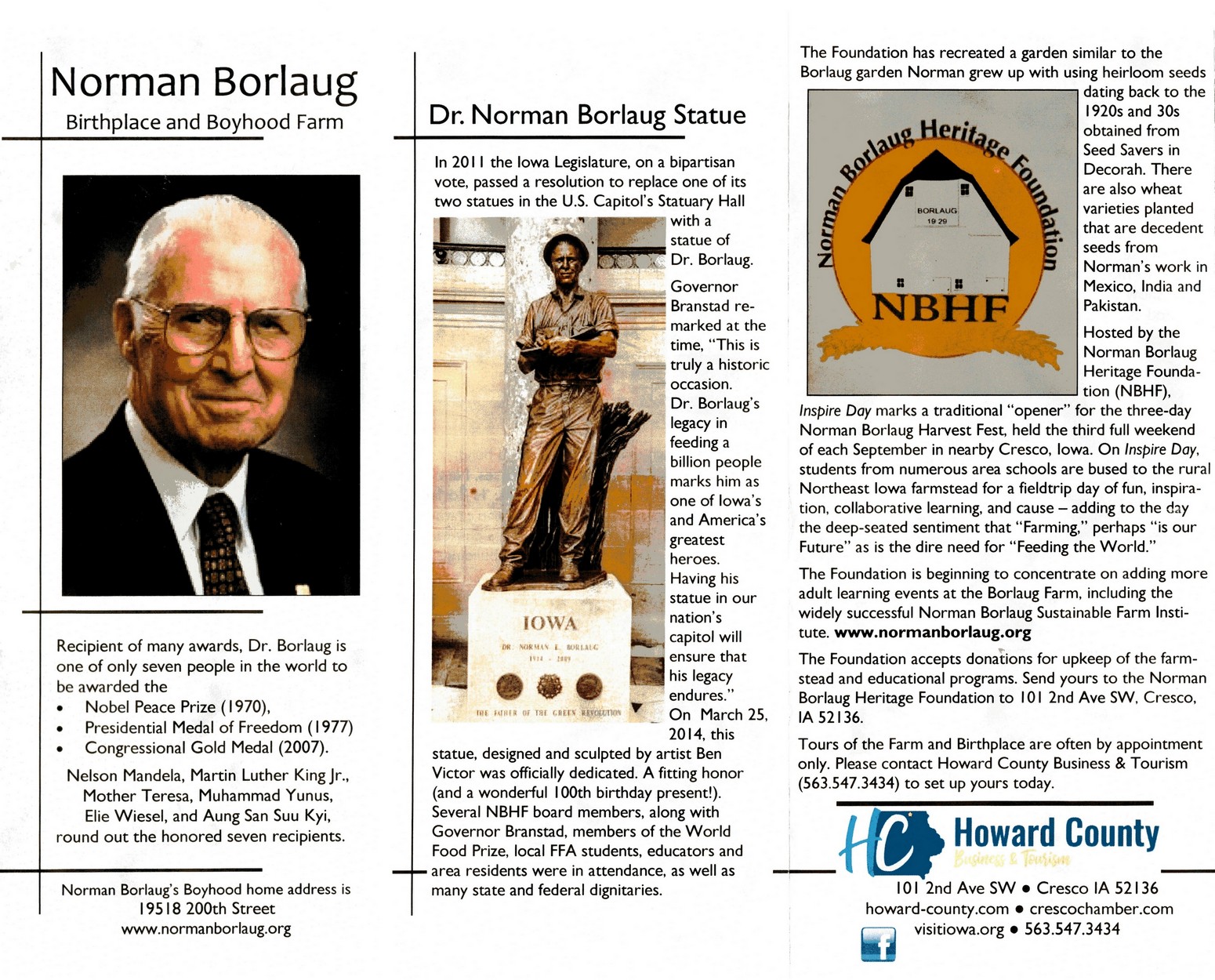

And that man was Dr Norman Ernest Borlaug (1914-2009), an agricultural scientist from northeast Iowa, whose research to develop short-strawed and high-yielding varieties staved off predicted widespread famines in the 1960s.

It was the beginning of an international effort to enhance agricultural productivity that endures to this day through the centers of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research or CGIAR, one of which is CIMMYT¹ (the International Center for Maize and Wheat Improvement in Mexico) where Borlaug spent many years as Director of the International Wheat Improvement Program (now the Global Wheat Program).

It was the beginning of an international effort to enhance agricultural productivity that endures to this day through the centers of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research or CGIAR, one of which is CIMMYT¹ (the International Center for Maize and Wheat Improvement in Mexico) where Borlaug spent many years as Director of the International Wheat Improvement Program (now the Global Wheat Program).

Dr Borlaug was awarded the 1970 Nobel Peace Prize for his work to promote global food supply, an act that contributes greatly to peace. And for having given a well-founded hope – the green revolution.

The expression “the green revolution” is permanently linked to Norman Borlaug’s name. He obtained a PhD in plant protection [from the University of Minnesota] at the age of 27, and worked in Mexico in the 1940s and 1950s to make the country self-sufficient in grain. Borlaug recommended improved methods of cultivation, and developed a robust strain of wheat – dwarf wheat – that was adapted to Mexican conditions. By 1956 the country had become self-sufficient in wheat.

Success in Mexico made Borlaug a much sought-after adviser to countries whose food production was not keeping pace with their population growth. In the mid-1960s, he introduced dwarf wheat into India and Pakistan, and production increased enormously. The expression “the green revolution” made Borlaug’s name known beyond scientific circles, but he always emphasized that he himself was only part of a team. (Source: www.nobelprize.org).

You can read his Nobel Prize lecture here.

Almost thirty years later, Borlaug returned to Oslo and reflected (in this lecture) on the progress that had been made since his 1970 Nobel Peace Prize.

He received many other awards in addition to the Nobel Peace Prize, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom (1977) and the Congressional Gold Medal (2006), one of only seven individuals worldwide to receive all three awards².

His is one of two Iowa statues in the US Capitol’s Statuary Hall, unveiled in 2014 and replacing one of the state’s existing statues. It was sculpted by Benjamin Victor. A duplicate stands on the University of Minnesota campus in St Paul, outside the building named in his honour.

His is one of two Iowa statues in the US Capitol’s Statuary Hall, unveiled in 2014 and replacing one of the state’s existing statues. It was sculpted by Benjamin Victor. A duplicate stands on the University of Minnesota campus in St Paul, outside the building named in his honour.

He founded the World Food Prize in 1986, a prestigious, international award given each year to honor the work of great agricultural scientists working to end hunger and improve the food supply.

It was initially sponsored and formed by businessman and philanthropist John Ruan Sr with support from the Governor and State Legislature of Iowa. Since 1987, there have been 55 laureates from 21 countries.

On 9 June 2017, Steph and I were on the last day of a 10 day road trip that had taken us from Atlanta, Georgia down to the coast at Savannah, then up through South Carolina, North Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, West Virginia, Kentucky, Illinois, Missouri, Iowa, and back to the Twin Cities in Minnesota. Almost 2800 miles.

We’d spent our last night in a suburb of Iowa City before setting off north to St Paul the following morning. In a little under 3 hours, we found ourselves in Cresco, the county seat of Howard County (just south of the state line with Minnesota) in the lovely Bluff Country that encompasses northeast Iowa, southeast Minnesota, and southwest Wisconsin.

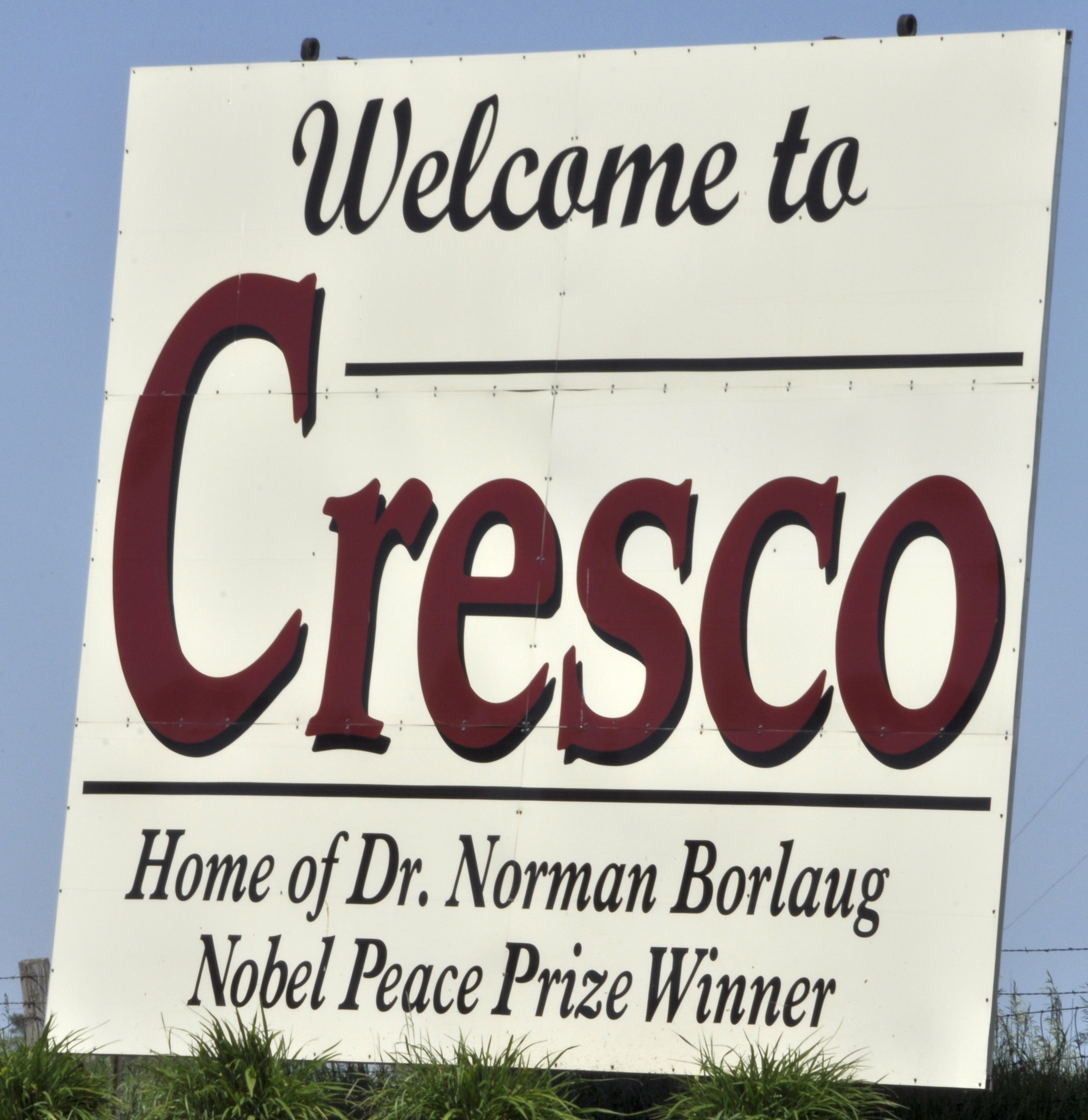

On the eastern outskirts of Cresco we came across this large billboard beside the road.

Anyway, as I stopped to take a photograph, I recalled having caught a glimpse—some miles south of Cresco—of a signpost to the ‘Borlaug Birthplace Farm’. Well, being somewhat pressed for time (and having another 180 miles to complete our journey to St Paul), we didn’t turn round and explore.

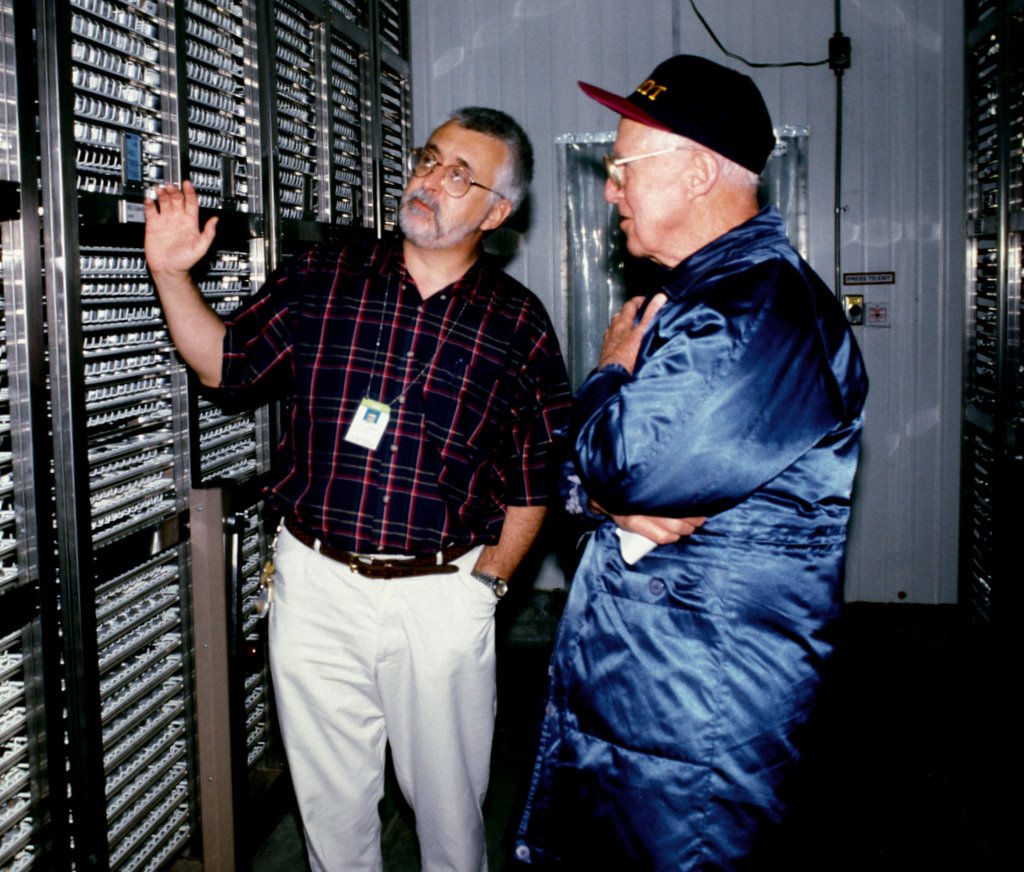

So it was just a vague hope that someday I might return, since I had met Dr Borlaug in April 1999 when he visited the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI, another of the CGIAR centers) in the Philippines where I was working at the time. It was a hope recently fulfilled.

Explaining how rice seeds are stored in the International Rice Genebank to Nobel Laureate Norman Borlaug

Earlier this year, I had contacted Seed Savers Exchange in Decorah, Iowa asking if Steph and I could have a ‘behind-the-scenes’ visit during our vacation in the USA, a vacation we have just returned from. It was then I discovered that Cresco was just a short drive west from Decorah, and I contemplated whether a tour of the Borlaug Birthplace and Boyhood Farms might be feasible.

So I contacted the Norman Borlaug Heritage Foundation (NBHF, set up in 2000) and very quickly received a reply that NBHF board members would be delighted to arrange a tour.

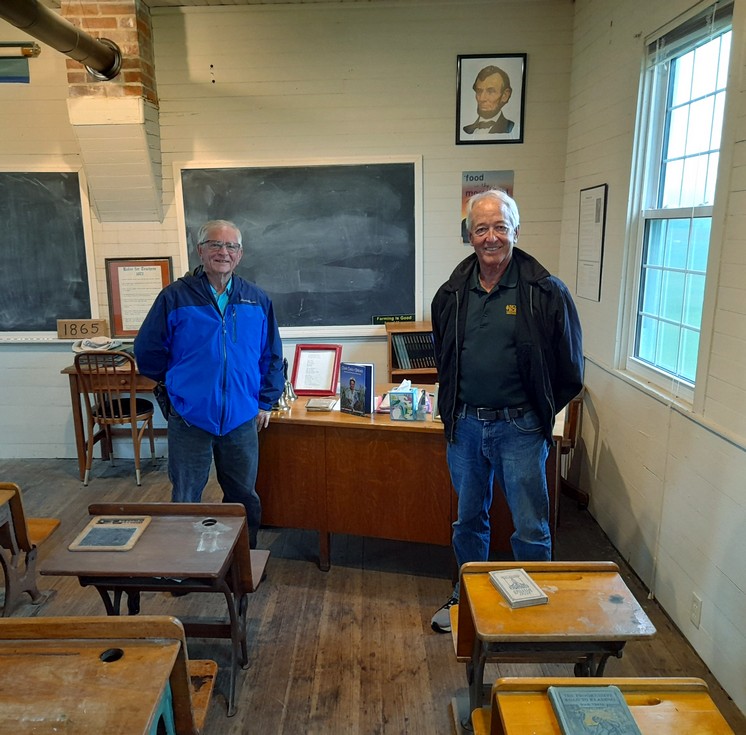

And that’s what we did on 3 June, setting off from Decorah in time to meet up with board members Tom Spindler (Tours) and Gary Gassett (Co-Treasurer) at the Borlaug Boyhood Farm.

NBHF board members Gary Gassett (L) and Tom Spindler (R) in the old school room on the Borlaug boyhood farm site.

Norman Borlaug came from humble beginnings, the great-grandson of Norwegian immigrants in the late 19th century.

Norman’s grandparents, Emma and Nels (and others of the Borlaug clan) settled in the Cresco area. They had three sons: Oscar, Henry (Norman’s father, second from left), and Ned.

Norman’s grandparents, Emma and Nels (and others of the Borlaug clan) settled in the Cresco area. They had three sons: Oscar, Henry (Norman’s father, second from left), and Ned.

Henry married Clara Vaala, and after Norman was born on 25 March 1914 in his grandparents house, the family lived there for several years. Norman had three younger sisters, Palma Lilian, Charlotte, and Helen (who was born and died in 1921).

The house is currently not open for visitors, as several parts are undergoing extensive repair and renovation.

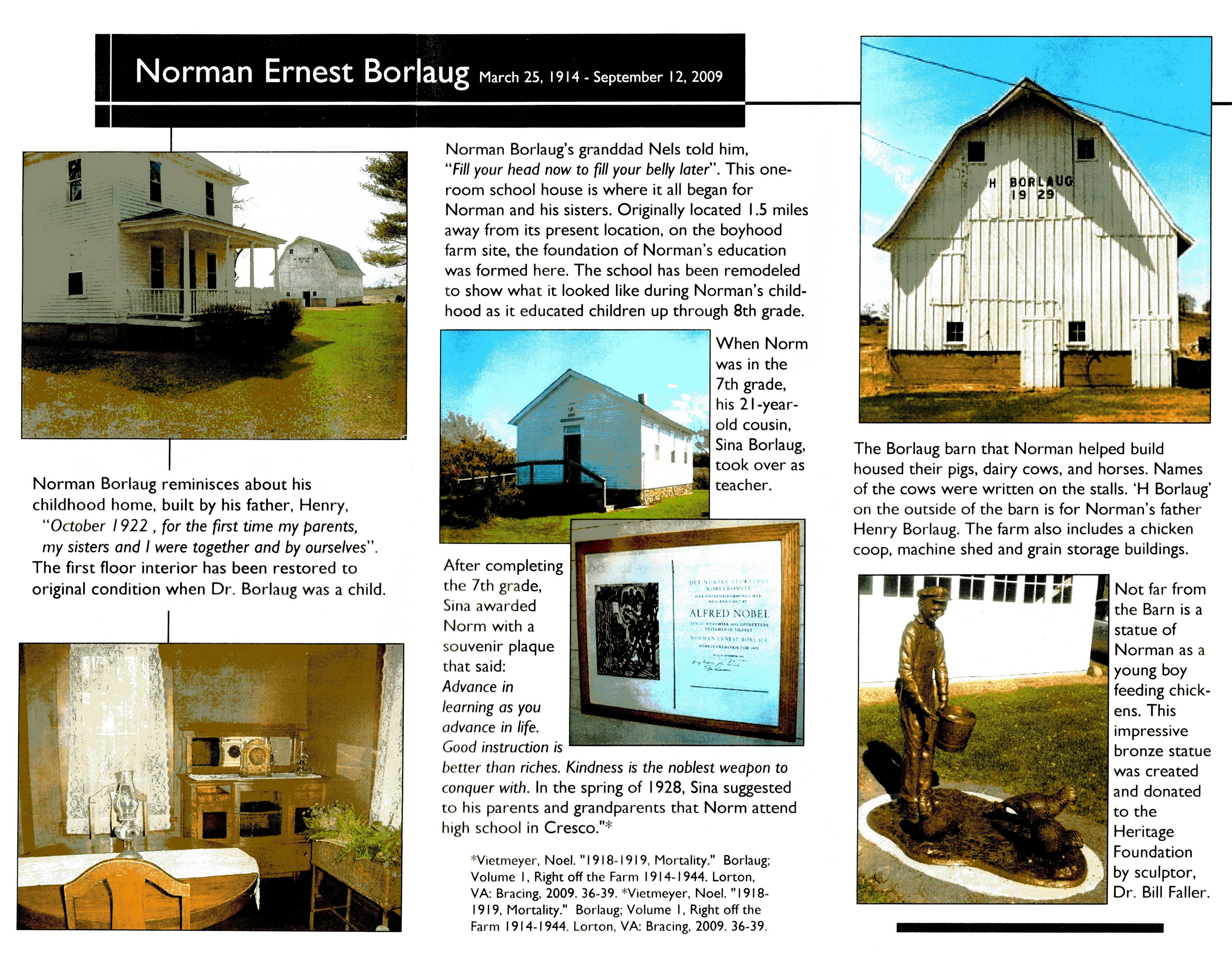

Henry and Clara bought a small plot of land (around 200 acres) less than a mile from their parent’s farm, but until he was 8, Norman continued to live with his grandparents. By then, in 1922, Henry and Clara had built their own home, ordered from Sears, Roebuck of Chicago. The original flatpack!

Life must have been hard on the Borlaug farm, the winters tough. Heating for the house came solely from the stove in the kitchen with warm(er) air rising to the four bedrooms bedrooms upstairs through a metal grill in the ceiling. There was an outhouse privy some 15 m or so from the back porch.

Besides the kitchen, with its hand pump to deliver water for washing, the other room on the ground floor was a combined parlour cum dining room.

On the front of the house there is a set of steps leading to a porch along the width of the house. Mature pine trees now surround the house, with a row to the front of the house planted by Norman when he was studying for his BS in forestry at the University of Minnesota (only later did he turn to plant pathology for his graduate studies).

On the farm, Henry eventually built a barn in 1929 to house their livestock There is a long chicken coop, beside which is a bronze statue of Norman as a boy feeding the chickens. It was created by Dr Bill Faller and donated to the NBHF, as was another nearby depicting Norman’s work around the world.

In one outhouse there’s a nice memento of Norman’s boyhood here: his initials inscribed on a wall.

In one outhouse there’s a nice memento of Norman’s boyhood here: his initials inscribed on a wall.

It’s said that Norman was an average student. From an early age, until Grade 8, he joined his classmates (of both Lutheran Norwegian and Catholic Czech descent – Czechs had settled in the area of Protivin and Spillville west of the Borlaug farms) in a one room schoolroom (built in 1865) that was originally located about a mile away from the farm. Norwegian children on one side of the room, the Czechs on the other.

At that time, most pupils reaching Grade 8 would leave full-time education and return to working on the family farm. But Norman’s teacher at the time, his cousin Sina Borlaug (right), encouraged both parents and grandparents to permit Norman to attend high school in Cresco. Which he did, boarding with a family there Monday to Friday, returning home each weekend to take on his fair share of the farm chores.

At that time, most pupils reaching Grade 8 would leave full-time education and return to working on the family farm. But Norman’s teacher at the time, his cousin Sina Borlaug (right), encouraged both parents and grandparents to permit Norman to attend high school in Cresco. Which he did, boarding with a family there Monday to Friday, returning home each weekend to take on his fair share of the farm chores.

And the rest is history, so to speak. He eventually made it to the University of Minnesota in St Paul to study forestry, spending some time working in that field before completing (in 1942) his PhD on variation and variability in the pathogen that causes flax wilt, Fusarium lini (now F. oxysporum f.sp. lini).

He joined a small group of scientists on a Rockefeller Foundation funded project in Mexico in 1944, and remained in Mexico until he retired. Among these colleagues was potato pathologist, Dr John Niederhauser, who became a colleague of mine as we developed a regional potato program (PRECODEPA) in the late 1970s.

Borlaug and Niederhauser were very keen baseball fans, and they introduced Little League Baseball to Mexico. That achievement is mentioned in one of the posters (below) in the Borlaug home, and our two NBHF guides, Tom and Garry, were surprised to learn that not only had I met Borlaug, but had worked with Niederhauser as well.

Active to the end of his life, Dr Borlaug passed away in Texas on 12 September 2009. His ashes were scattered at several places, including the Iowa farms.

To the end of his life he was passionate about the need for technology to enhance agricultural productivity. And one point of view remained as strong as ever: peace and the eradication of human misery were underpinned by food security.

It was a fascinating tour of the Borlaug Birthplace and Boyhood Farms, and Steph and I are grateful to Tom and Garry for taking the time (over 2.5 hours) to give us a personal tour.

The NBHF has several programs, including internships and one designed especially for schoolchildren to make them aware of Borlaug’s legacy, and why it is important. You can find much more information on the Foundation website.

¹ Many of Dr Borlaug’s day-to-day belongings (including his typewriter) are displayed in the office suite he occupied at CIMMYT. The photos are courtesy of two former IRRI colleagues, plant breeder Dr Mark Nas and Finance Manager Remy Labuguen who now work at CIMMYT.

Dr Borlaug stepped down as head of CIMMYT’s wheat program around 1982, but he remained as active as ever. He especially enjoyed spending time with trainees, passing on his wealth of knowledge about wheat improvement to the next generation of breeders and agronomists.

In this photo, he is showing trainees how to select viable seeds at CIMMYT’s Obregon Wheat Research Station in the spring of 1992.

One of my colleagues at IRRI, Gene Hettel, was the communications specialist in the wheat program at CIMMYT between 1986 and 1995.

Gene told me that Borlaug’s office was directly above mine—that made it handy for when he had editorial chores for me. Sometimes he would call me up to his office if he had a really big job—maybe a major book chapter to edit. Other times he dropped by my office with a grin on his face: “Are you busy?”

Here they are together in the wheat plots just outside their offices to get away from all the paperwork and just “talk” to the plants!

² The other six are: Nelson Mandela (South Africa), Martin Luther King Jr (USA), Mother Teresa (Albania-India), Muhammad Yunus (Bangladesh), Elie Wiesel (USA), and Aung San Suu Kyi (Myanmar). Mohammad Yunus (currently Chief Advisor of the interim government of Bangladesh) was a member of IRRI’s Board of Trustees (1989 to 1994) when I joined the institute in 1991.

A great blog on an extraordinary person! Thanks!

LikeLike