A life without music is no life . . .

I need music around me almost all day long. Much of the time it’s the music I have stored on my iPod linked up to my stereo system; so am able to enjoy CD quality as I listen. But I do have some CDs that I’ve never ripped, especially my collection of classical music.

They say that looking at someone’s CD collection says a lot about them. And before you ask, yes, I do have my collection sorted alphabetically – it’s the taxonomist in me. My tastes are broad and varied: rock, pop, folk (especially Irish and Northumbrian pipe music), country, and classical. So I often wonder which eight records I would choose to take on an imaginary desert island.

Desert island? Have I completely lost the plot? Not at all. I’m referring to a BBC radio program first broadcast in 1942, and which celebrated its 70th anniversary recently (the guest was Sir David Attenborough). The format of Desert Island Discs is simple. Each week a guest is invited to choose the eight pieces of music, a book (in addition to the Complete Works of Shakespeare and the Bible), and one luxury that they would take with them as an imaginary castaway on a desert island. Discussion of this music then permits a broader appreciation of the guest’s life, career and other ideas. The current presenter is Kirsty Young, but the original presenter (who actually devised the program), Roy Plomley, was in charge until his death in 1985.

So when you think about it, the choices have to be ones that you’ll never (well, hardly ever) tire of listening to. For what it’s worth, and in no particular order, here are my eight pieces of music – but the list could change tomorrow (and through the wonders of Google and YouTube, I’ve been able to find a great link to each piece for your enjoyment):

Roberta Flack: Killing Me Softly with His Song

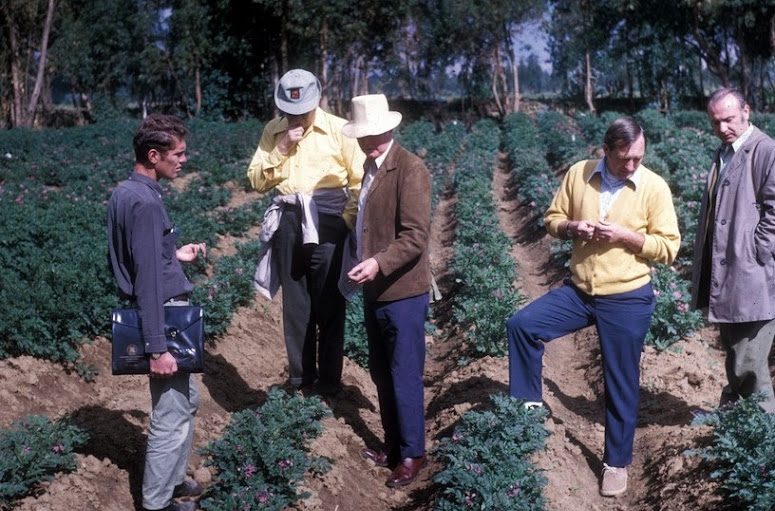

I’m not really a Roberta Flack fan – but this song has special memories for me, and these come flooding back whenever I hear it played (not so frequently these days). When I joined the International Potato Center (CIP) in January 1973 this song had just been released and was played all the time on radio stations in Lima. So this song takes me back to the beginning of my career in international agricultural research.

I’m not really a Roberta Flack fan – but this song has special memories for me, and these come flooding back whenever I hear it played (not so frequently these days). When I joined the International Potato Center (CIP) in January 1973 this song had just been released and was played all the time on radio stations in Lima. So this song takes me back to the beginning of my career in international agricultural research.

The Beatles: We Can Work It Out

Released in December 1965, as a double A side with Day Tripper. As a teenager in the 60s, I grew up with The Beatles – I was 14 when She Loves You was released and the group became an overnight sensation. I was hooked, and bought nearly all their LPs on vinyl (which were stolen during a burglary in Turrialba, Costa Rica in 1978 – but that’s another story).

When I moved to CDs (in 1991) I replaced all my Beatles albums. I could have chosen any one of many of their phenomenal output, but We Can Work It Out has always been a favorite, and the title reflects, to a certain extent, my philosophy in life. At one of the IRRI 50th anniversary events held in Manila in December 2009, a group called Area One performed a set of Beatles numbers, and played We Can Work It Out just for me! Click here to watch.

Fleetwood Mac: Don’t Stop

The first CD I ever purchased (in 1991) was Fleetwood Mac Greatest Hits, just prior to my move to the Philippines to join IRRI. I’d never really been a fan of the group, although they were familiar to me, in a distant sort of way. Since then, I have become slightly obsessive with their music, and certainly Rumours (released in 1977, and which went on to become one of the best selling albums ever) is a classic. Don’t Stop can be taken as a song of great optimism – even though Rumours was recorded when Fleetwood Mac and their tangled personal relationships were in meltdown. Don’t Stop was adopted by the Clinton campaign for the presidency in 1992, and Fleetwood Mac re-formed specially to play at the Clinton Inauguration Ball on 20 January 1993.

The first CD I ever purchased (in 1991) was Fleetwood Mac Greatest Hits, just prior to my move to the Philippines to join IRRI. I’d never really been a fan of the group, although they were familiar to me, in a distant sort of way. Since then, I have become slightly obsessive with their music, and certainly Rumours (released in 1977, and which went on to become one of the best selling albums ever) is a classic. Don’t Stop can be taken as a song of great optimism – even though Rumours was recorded when Fleetwood Mac and their tangled personal relationships were in meltdown. Don’t Stop was adopted by the Clinton campaign for the presidency in 1992, and Fleetwood Mac re-formed specially to play at the Clinton Inauguration Ball on 20 January 1993.

The video shows the group performing at that event (not the best performance, however – watch Michael Jackson and other celebrities join FM on stage towards the end of the video). In 2006 I went to a Fleetwood Mac concert (along with 60,000 + fans) in St Paul, Minnesota. What an event – you could feel the music vibrating every organ in your body. And I’m not ashamed to say that I just couldn’t hold back the tears; what an emotional event. Pity that Christine McVee (née Perfect, and brother to entomologist John Perfect who worked at IRRI for a while in the 1980s) had decided no longer to tour with the group. A great concert, nevertheless.

Pink Floyd: Comfortably Numb (The Wall)

I’ve become an avid fan of Pink Floyd only in recent years, and really taken with the guitar mastery of Dave Gilmour. His solos in this song makes the hairs on the back of my head stand up. The version in the video link is from a Roger Waters concert of The Wall at the O2 Arena in London in 2011, with a special appearance of Dave Gilmour. I was never really aware of the group in the 60s, and was abroad during the 70s when they really made a name for themselves. We didn’t hear much Pink Floyd on the radio in Peru or Costa Rica. However, I do remember, on one trip to Guatemala in late 1979-early 1980, switching on the TV in my hotel room and seeing a video of Another Brick in The Wall. I was fascinated by ‘the marching hammers’.

Dire Straits: Sultans of Swing

Dire Straits – what more can I say.

I have been a consistent fan since the early 1980s, and have followed Mark Knopfler ever since Dire Straits broke up. Mark is probably the greatest guitarist performing today. Sultans of Swing is a vehicle for Mark’s virtuosity, and although included on the album Dire Straits, it was the group’s first release as a single in 1978, but didn’t become a hit until the following year when it was re-released. Even today, Mark cannot play a concert without a rendition of Sultans of Swing. I was fortunate to go to one of his concerts at the LG Arena in Birmingham in May 2010 (tickets were a Christmas present from my daughters), and the live performance was stupendous.

Chopin: Mazurka No. 23 in D Major, Op. 33, No. 2 (but I’d like all the mazurkas, waltzes, and polonaises).

I’ve always appreciated the music of Fryderyk Chopin. So I felt privileged during a visit to Poland in 1989 (I gave a series of lectures on crop evolution and genetic resources at a couple of research institutes) to visit Chopin’s birthplace. Some of his music was being played in the house that is now a museum. And as I strolled around the garden, I could hear this particular mazurka. Although it’s a favorite, it’s also a proxy for all his other wonderful music. The version played here is by Turkish concert pianist, Idil Biret.

I’ve always appreciated the music of Fryderyk Chopin. So I felt privileged during a visit to Poland in 1989 (I gave a series of lectures on crop evolution and genetic resources at a couple of research institutes) to visit Chopin’s birthplace. Some of his music was being played in the house that is now a museum. And as I strolled around the garden, I could hear this particular mazurka. Although it’s a favorite, it’s also a proxy for all his other wonderful music. The version played here is by Turkish concert pianist, Idil Biret.

Gluck: Che farò senza Euridice (and the whole opera, of course)

I’ve known this particular aria from Gluck’s opera Orfeo ed Euridice since I was a small boy. But the version I knew then was by the famous English contralto, Kathleen Ferrier, who died of cancer in 1953. But her version was sung in English as What is Life (this recording is from 1946). In the 1990s I used to travel quite often from the Philippines to Europe (especially Rome) in my capacity as Head of the CGIAR Inter-Center Working on Genetic Resources, and mostly flew with Lufthansa then. Lufthansa had (and I assume they still do) a terrific classical music audio stream, and on one journey I came across the version of Che farò senza Euridice listed here. In many productions the part of Orfeo is sung by a contralto (there’s a video of Dame Janet Baker on YouTube), but in fact it was originally written for a counter tenor. In this recording, counter tenor Derek Lee Ragin gives a stunning performance of the aria – you will be amazed that you are listening to a male singer.

I’ve known this particular aria from Gluck’s opera Orfeo ed Euridice since I was a small boy. But the version I knew then was by the famous English contralto, Kathleen Ferrier, who died of cancer in 1953. But her version was sung in English as What is Life (this recording is from 1946). In the 1990s I used to travel quite often from the Philippines to Europe (especially Rome) in my capacity as Head of the CGIAR Inter-Center Working on Genetic Resources, and mostly flew with Lufthansa then. Lufthansa had (and I assume they still do) a terrific classical music audio stream, and on one journey I came across the version of Che farò senza Euridice listed here. In many productions the part of Orfeo is sung by a contralto (there’s a video of Dame Janet Baker on YouTube), but in fact it was originally written for a counter tenor. In this recording, counter tenor Derek Lee Ragin gives a stunning performance of the aria – you will be amazed that you are listening to a male singer.

JS Bach: The Brandenburg Concertos (all six – I’m cheating)

I don’t think any music selection would be complete without a piece by Johan Sebastian Bach. And so I have chosen The Brandenburg Concertos – I find it hard to choose just one of the six. The complexity – and timeless quality – of Bach’s music is a continued inspiration. The video shows the Concerto No. 1, Allegro Moderato.

I don’t think any music selection would be complete without a piece by Johan Sebastian Bach. And so I have chosen The Brandenburg Concertos – I find it hard to choose just one of the six. The complexity – and timeless quality – of Bach’s music is a continued inspiration. The video shows the Concerto No. 1, Allegro Moderato.

So, these are my eight choices. I could have included more from Eric Clapton, Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, The Traveling Wilburys, R.E.M., ELO, Crowded House, South American music, The Chieftains, Alison Krauss, and of course a host of baroque composers such as Vivaldi, Boccherini, Haydn, Mozart, and later composers such as Beethoven, Schubert, etc. If I were to make the list in 12 months time, maybe there would be some changes.

And the extras . . .

So what would be my one luxury item and book? Well, I think I’d choose a pair of binoculars – that way I could spend some time birdwatching (assuming my desert island is suitably forested), and to scan the horizon for passing ships to rescue me. And the book? Well, since I reckon I’d have a lot of time on my hands to play word games, I think a copy of Roget’s Thesaurus would be very useful. Incidentally, the Bible would have to be the King James 1611 – I’m not a religious person, but the English text of this version is wonderful and has given so many phrases to modern English usage (and it just celebrated its 400th anniversary).

PS. I’m also an ABBA fan!

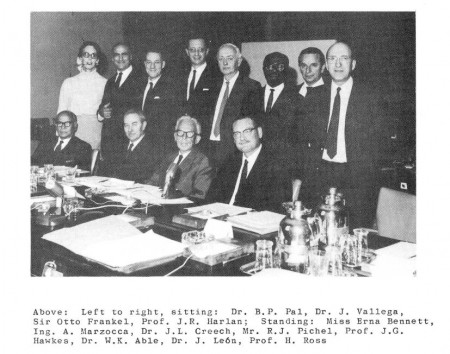

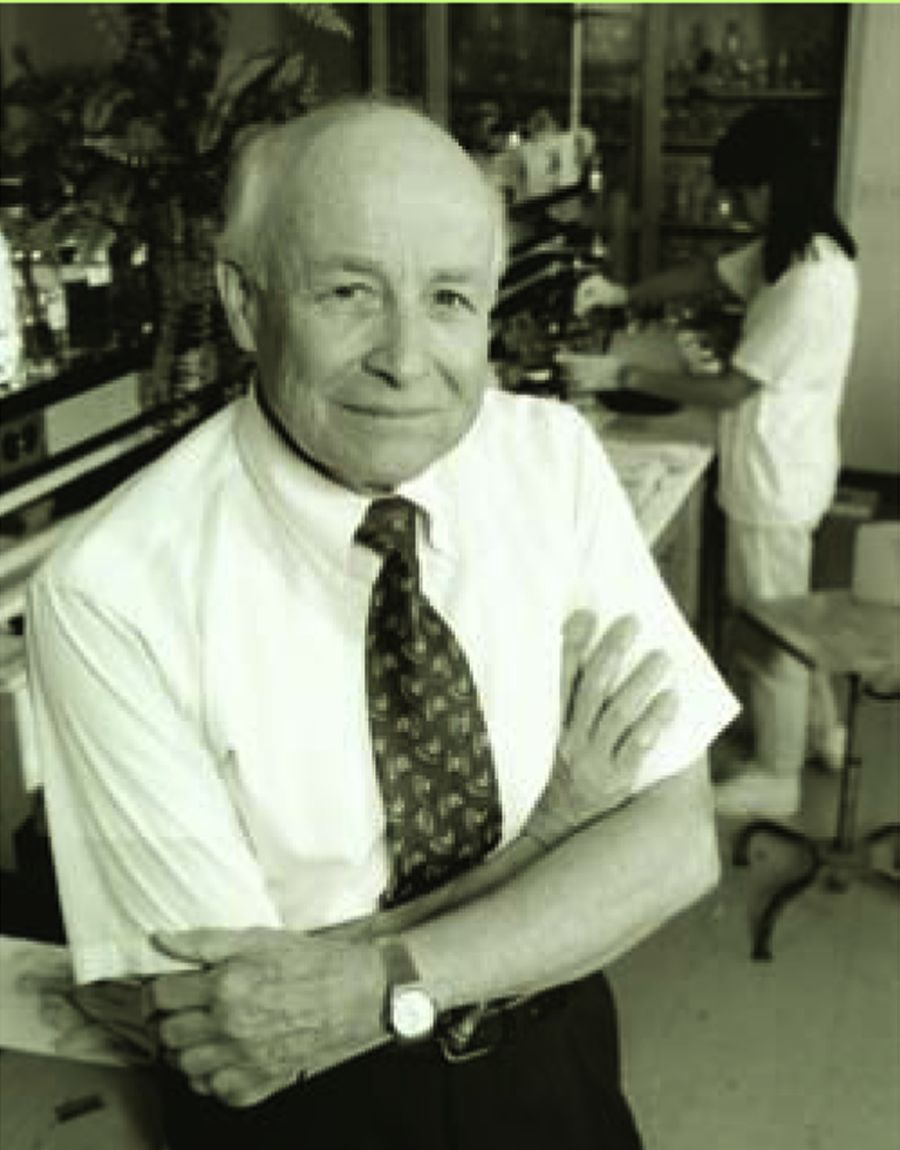

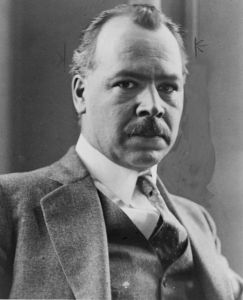

John Gregory ‘Jack’ Hawkes – botanist, educator, and visionary – was born in Bristol in 1915. After completing his secondary education at Cheltenham Grammar School in 1934, he won a place at Christ’s College, University of Cambridge, graduating with a BA (Natural Sciences, first class honours) in 1937. His MA was awarded in 1938, and he completed his PhD in 1941 under the supervision of the noted potato breeder and historian, Dr Redcliffe N Salaman FRS. The university awarded Jack the ScD degree in 1957.

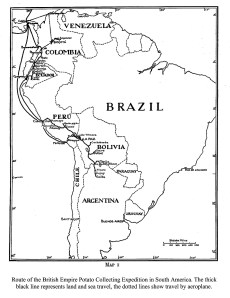

John Gregory ‘Jack’ Hawkes – botanist, educator, and visionary – was born in Bristol in 1915. After completing his secondary education at Cheltenham Grammar School in 1934, he won a place at Christ’s College, University of Cambridge, graduating with a BA (Natural Sciences, first class honours) in 1937. His MA was awarded in 1938, and he completed his PhD in 1941 under the supervision of the noted potato breeder and historian, Dr Redcliffe N Salaman FRS. The university awarded Jack the ScD degree in 1957. On graduation in 1937 Jack successfully applied for the position of assistant to Dr PS Hudson, Director of the Imperial Bureau of Plant Breeding and Genetics in Cambridge, for an expedition to Lake Titicaca in the South American Andes. In the event this expedition did not materialize due to Hudson’s poor health, but a more comprehensive expedition was then planned for 1939, led by EK Balls, a professional plant collector. Thus began Jack’s lifelong interest in ‘the humble spud’.

On graduation in 1937 Jack successfully applied for the position of assistant to Dr PS Hudson, Director of the Imperial Bureau of Plant Breeding and Genetics in Cambridge, for an expedition to Lake Titicaca in the South American Andes. In the event this expedition did not materialize due to Hudson’s poor health, but a more comprehensive expedition was then planned for 1939, led by EK Balls, a professional plant collector. Thus began Jack’s lifelong interest in ‘the humble spud’.

In addition to his lifelong research on potatoes, Jack also spearheaded scientific interest in the Solanaceae plant family that also includes tomato, tobacco, chili peppers, and eggplant, and many species with pharmaceutical properties. With colleagues at Birmingham in the late 1950s he developed serological methods to study relationships between potato species. He was also one of the leading lights to produce a computer-mapped Flora of Warwickshire, a first of its kind, published in 1971.

In addition to his lifelong research on potatoes, Jack also spearheaded scientific interest in the Solanaceae plant family that also includes tomato, tobacco, chili peppers, and eggplant, and many species with pharmaceutical properties. With colleagues at Birmingham in the late 1950s he developed serological methods to study relationships between potato species. He was also one of the leading lights to produce a computer-mapped Flora of Warwickshire, a first of its kind, published in 1971.