When the late Professor Jack Hawkes was appointed to a lectureship in botany at the University of Birmingham in 1952, he had already been working on potatoes for more than a decade. And immediately prior to arriving in Birmingham he’d spent three years in Colombia helping to establish a national potato breeding program. From then until his retirement in 1982 – and indeed throughout the 1980s – Birmingham was an important center for potato studies.

When the late Professor Jack Hawkes was appointed to a lectureship in botany at the University of Birmingham in 1952, he had already been working on potatoes for more than a decade. And immediately prior to arriving in Birmingham he’d spent three years in Colombia helping to establish a national potato breeding program. From then until his retirement in 1982 – and indeed throughout the 1980s – Birmingham was an important center for potato studies.

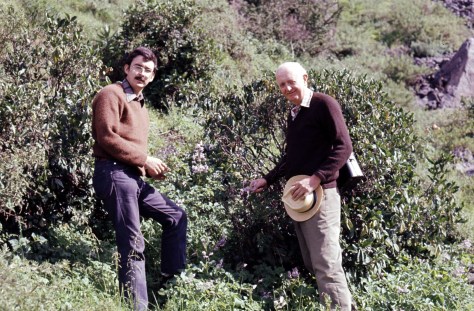

The potato germplasm that Hawkes collected (with EK Balls and W Gourlay in the 1938-39 expedition to South America) eventually formed the basis of the Empire then Commonwealth Potato Collection, maintained at the James Hutton Institute in Scotland. Throughout the 50s, 60s, 70s, and 80s Jack also had a large collection of wild potato (Solanum) species at Birmingham. This was a special quarantine collection; in the 1980s for potato quarantine purposes, Birmingham was effectively outside the European Union! For more than two decades Jack was assisted by horticultural technician Dave Downing, seen in the photo below. At the end of the 1980s we decided to donate the seed stocks from Jack’s collection to the Commonwealth Potato Collection, and it went into quarantine in Scotland. As the various lines were tested for viruses diseases they were introduced into the main collection. Jack used this collection to train a succession of PhD students on the biosystematics of potatoes. I continued with this tradition after I joined the University of Birmingham in 1981. My first student graduated in 1982 (after I had taken over supervision from Jack).

Here is the list of University of Birmingham PhD students who worked on potatoes, as far as I can remember. All of them from 1975 (with the exception of Ian Gubb) had also attended the MSc course on genetic resources:

Here is the list of University of Birmingham PhD students who worked on potatoes, as far as I can remember. All of them from 1975 (with the exception of Ian Gubb) had also attended the MSc course on genetic resources:

Richard Lester (UK), 1962. Taught at Makerere University in Uganda, before joining the Dept. of Botany at Birmingham in 1969. Retired in 2002, and died in 2006. Studied the biochemical systematics of Mexican wild Solanum species. The species Solanum lesteri is named after him.

Richard Lester (UK), 1962. Taught at Makerere University in Uganda, before joining the Dept. of Botany at Birmingham in 1969. Retired in 2002, and died in 2006. Studied the biochemical systematics of Mexican wild Solanum species. The species Solanum lesteri is named after him.

Richard Tarn (UK), 1967. Emigrated to Canada in 1968, and joined Agriculture Canada as a potato breeder in Fredericton, New Brunswick. Retired in 2008. Studied the origin of ploidy levels in wild species.

Richard Tarn (UK), 1967. Emigrated to Canada in 1968, and joined Agriculture Canada as a potato breeder in Fredericton, New Brunswick. Retired in 2008. Studied the origin of ploidy levels in wild species.

Katsuo Armando Okada (Argentina), 1970 (?). Retired. Was with IBPGR for a while in the 1980s (?) in Colombia. Studied the origin of Solanum x rechei from Argentina.

Katsuo Armando Okada (Argentina), 1970 (?). Retired. Was with IBPGR for a while in the 1980s (?) in Colombia. Studied the origin of Solanum x rechei from Argentina.

Phillip Cribb (UK), 1972. He joined the Royal Botanic Gardens – Kew, and became a renowned orchid taxonomist. Studied the origin of the tetraploid Solanum tuberosum ssp. andigena.

Phillip Cribb (UK), 1972. He joined the Royal Botanic Gardens – Kew, and became a renowned orchid taxonomist. Studied the origin of the tetraploid Solanum tuberosum ssp. andigena.

Mike Jackson (UK), 1975. Studied the triploid cultigen Solanum x chaucha. Joint with CIP and Roger Rowe.

David Astley (UK), 1975. Became the curator of the vegetable genebank at Wellesbourne (now the Warwick Crop Centre). Studied the Bolivian wild species Solanum sucrense. The species S. astleyi is named after Dave.

David Astley (UK), 1975. Became the curator of the vegetable genebank at Wellesbourne (now the Warwick Crop Centre). Studied the Bolivian wild species Solanum sucrense. The species S. astleyi is named after Dave.

Zosimo Huaman (Peru), 1976. He returned to the International Potato Center (CIP) in Lima, and continued working with the germplasm collection until December 2000; he then began work with several NGOs on biodiversity issues in Peru. Studied the origin of the diploid cultigen Solanum x ajanhuiri. Joint with CIP and Roger Rowe.

Zosimo Huaman (Peru), 1976. He returned to the International Potato Center (CIP) in Lima, and continued working with the germplasm collection until December 2000; he then began work with several NGOs on biodiversity issues in Peru. Studied the origin of the diploid cultigen Solanum x ajanhuiri. Joint with CIP and Roger Rowe.

Peter Schmiediche (Germany), 1977. He continued working with CIP as a potato breeder (for resistance to bacterial wilt), and was later CIP’s regional leader based in Indonesia. Now retired and sharing his time between Texas (where his children settled) and his native Berlin. Studied the bitter potatoes Solanum x juzepczukii (3x) and S. x curtilobum (5x). Joint with CIP and Roger Rowe.

Peter Schmiediche (Germany), 1977. He continued working with CIP as a potato breeder (for resistance to bacterial wilt), and was later CIP’s regional leader based in Indonesia. Now retired and sharing his time between Texas (where his children settled) and his native Berlin. Studied the bitter potatoes Solanum x juzepczukii (3x) and S. x curtilobum (5x). Joint with CIP and Roger Rowe.

Luis Lopez (Colombia), 1979. Studied wild species in the Series Conicibaccata.

Lenny Taylor (UK), late 1970s. I don’t remember his thesis topic, but I think it had something to do with tetraploid forms. He joined the Potato Marketing Board (now the Potato Council) but I’ve lost contact.

Lynne Woodwards (UK), 1982. Studied the Mexican tetraploid Solanum hjertingii, which does not show enzymic blackening in cut tubers.

Rene Chavez (Peru), 1984. He returned to the University of Tacna, Peru, but also spent time at CIAT in Cali, Colombia studying a large wild cassava (Manihot spp.) collection. He sadly died of cancer a couple of years ago. Studied wide crossing to transfer resistance to tuber moth and potato cyst nematode. Joint with CIP and Peter Schmiediche.

Elizabeth Newton (UK), 1987? Studied sexually-transmitted viruses in potato. Joint with former CIP virologist Roger Jones (now at the University of Western Australia) at the MAFF Harpenden Laboratory.

Denise Clugston (UK), 1988. Studied embryo rescue and protoplast fusion to use wild species in potato breeding.

Carlos Arbizu (Peru), 1990. An expert on minor Andean tuber crops, he came from the University of Ayacucho. Spent time working in the germplasm program at CIP. Studied the origin and value of resistance to spindle tuber viroid in Solanum acaule. Joint with CIP and principal virologist Luis Salazar (who gained his PhD while studying at the Scottish Crop Research Institute in Dundee).

Carlos Arbizu (Peru), 1990. An expert on minor Andean tuber crops, he came from the University of Ayacucho. Spent time working in the germplasm program at CIP. Studied the origin and value of resistance to spindle tuber viroid in Solanum acaule. Joint with CIP and principal virologist Luis Salazar (who gained his PhD while studying at the Scottish Crop Research Institute in Dundee).

Ian Gubb (UK), 1991. Studied the biochemical basis of non-blackening in Solanum hjertingii. Joint with the Food Research Institute, Norwich.

Susan Juned (UK), 1994. Now a sustainable technology consultant, Sue is an active local government councillor, and has stood for election to parliament on a couple of occasions for the Liberal Democrats. Studied somaclonal variation in potato cv. Record; this commercial contract research was commissioned by United Biscuits.

Susan Juned (UK), 1994. Now a sustainable technology consultant, Sue is an active local government councillor, and has stood for election to parliament on a couple of occasions for the Liberal Democrats. Studied somaclonal variation in potato cv. Record; this commercial contract research was commissioned by United Biscuits.

David Tay (Malaysia), 2000. He worked in Australia and then was Director of the USDA Ornamental Plant Germplasm Center in Columbus, Ohio, but returned to CIP as head of the genetic resources unit in 2007. He’s now left CIP. I think he worked on diploid cultivated species. Joint with CIP. Not sure why his PhD is dated 2000, as he’d been in CIP in the late 70s.

David Tay (Malaysia), 2000. He worked in Australia and then was Director of the USDA Ornamental Plant Germplasm Center in Columbus, Ohio, but returned to CIP as head of the genetic resources unit in 2007. He’s now left CIP. I think he worked on diploid cultivated species. Joint with CIP. Not sure why his PhD is dated 2000, as he’d been in CIP in the late 70s.

I also supervised several MSc students who completed dissertations on potatoes (Reiner Freund from Germany, and Beatrice Male-Kayiwa and Nelson Wanyera from Uganda).

The Birmingham link with CIP is rather interesting. In the early 70s, staff at CIP seemed to have a graduate degree in the main from one of four universities: Cornell, North Carolina State, Wisconsin, or Birmingham.

Besides the Birmingham PhD students who went on to work at CIP, my wife Stephanie (MSc 1972, who had been working with the Commonwealth Potato Collection from November 1972 – June 1973 when it was still based at the Scottish Plant Breeding Station – now closed) joined the Breeding and Genetics Dept. at CIP in July 1973.

Roger Rowe, who had been in charge of the US potato genebank in Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin, also joined CIP in July 1973 as head of the Breeding and Genetics Dept. He co-supervised (with Jack Hawkes) a number of Birmingham PhD students.

Roger Rowe, who had been in charge of the US potato genebank in Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin, also joined CIP in July 1973 as head of the Breeding and Genetics Dept. He co-supervised (with Jack Hawkes) a number of Birmingham PhD students.

With the closure of Jack’s collection at Birmingham we were able to develop other potato research ideas since there were no longer any quarantine restrictions. In 1984 we secured funding from the Overseas Development Administration (now the Department for International Development – DfID) to work on single seed descent (SSD) from diploid potatoes to produce true potato seed (TPS). Diploids are normally self-incompatible, but evidence from a range of species had shown that such incompatibility could be broken and transgressive segregants selected. The work was originally started in collaboration with the Plant Breeding Institute (PBI) in Cambridge, but when the Thatcher government privatized the PBI and sold it to Monsanto in 1988, we continued the work at Birmingham. After a further year we hit a ‘biological brick wall’ and decided that the resources needed would be too great to warrant continued effort. This paper reflects our philosophy on TPS [1]. Another paper [2] spells out the approach we planned.

[1] Jackson, M.T., 1987. Breeding strategies for true potato seed. In: G.J. Jellis & D.E. Richardson (eds.), The Production of New Potato Varieties: Technological Advances. Cambridge University Press, pp. 248-261.

[2] Jackson, M.T., L. Taylor & A.J. Thomson, 1985. Inbreeding and true potato seed production. In: Report of a Planning Conference on Innovative Methods for Propagating Potatoes, held at Lima, Peru, December 10-14, 1984, pp. 169-179.

I joined CIP in January 1973 as Associate Taxonomist, charged with the task of collecting potato varieties and helping them to maintain the large germplasm collection, that grew to at least 15,000 separate entries (or clonal accessions), but was reduced to a more manageable number through the elimination of duplicate samples. The germplasm collection was planted each year from October through April, coinciding with the most abundant rains, in the field in Huancayo, central Peru at an altitude of more than 3,100 meters.

I joined CIP in January 1973 as Associate Taxonomist, charged with the task of collecting potato varieties and helping them to maintain the large germplasm collection, that grew to at least 15,000 separate entries (or clonal accessions), but was reduced to a more manageable number through the elimination of duplicate samples. The germplasm collection was planted each year from October through April, coinciding with the most abundant rains, in the field in Huancayo, central Peru at an altitude of more than 3,100 meters.

that endeavour. In May 1973 I joined my colleague Zosimo Huaman to collect potatoes in the Departments of Ancash and La Libertad, to the north of Lima. The highest mountains in Peru are found in Ancash, and our route took us through into the

that endeavour. In May 1973 I joined my colleague Zosimo Huaman to collect potatoes in the Departments of Ancash and La Libertad, to the north of Lima. The highest mountains in Peru are found in Ancash, and our route took us through into the

of a minor Andean tuber crop called oca (Oxalis tuberosa). We went to the village of Cuyo Cuyo, more than 100 km north of Puno in southern Peru. Dropping down from the altiplano, the road hugs the sides of the valley, and is often blocked by landslides (a very common occurrence throughout Peru in the rainy season). Along the way – and due to the warmer air rising from the selva (jungle) to the east – the vegetation is quite luxurious in places, as the white begonia below shows (the flowers were about 8 cm in diameter). Eventually the valley opens out, with terraces on all sides. These terraces (or andenes) are ancient structures constructed by the Incas to make the valley more productive.

of a minor Andean tuber crop called oca (Oxalis tuberosa). We went to the village of Cuyo Cuyo, more than 100 km north of Puno in southern Peru. Dropping down from the altiplano, the road hugs the sides of the valley, and is often blocked by landslides (a very common occurrence throughout Peru in the rainy season). Along the way – and due to the warmer air rising from the selva (jungle) to the east – the vegetation is quite luxurious in places, as the white begonia below shows (the flowers were about 8 cm in diameter). Eventually the valley opens out, with terraces on all sides. These terraces (or andenes) are ancient structures constructed by the Incas to make the valley more productive.