Well, if you take into account an iconic landscape, Cheddar Gorge, that we drove up on the next to last day, then it’s millions of years. But let’s not quibble. More of that later.

Steph and I have just spent an excellent week (5-13 September) exploring National Trust and English Heritage properties in Somerset and west Wiltshire. From our home in North Tyneside it was a round trip of almost 700 miles (by the routes we took) to the cottage we rented (through Vrbo) in Prestleigh a couple of miles south of Shepton Mallet in central Somerset. An excellent location for moving around this region.

Over the week, we visited nine National Trust properties in Somerset and west Wiltshire (plus Cheddar Gorge that is owned and managed by the National Trust on the north side) and the two on the way south, plus four properties owned by English Heritage.

Once in Somerset, we were rather lucky with the weather, especially over the first four days when there was hardly any rain. The second half of the week was more unsettled, but with judicious use of the weather radar maps and forecasts, we could decide which direction to head to and avoid the worst of the showers. And it worked out just fine.

I’ll be posting separate stories about some of the properties we visited, and at the end of this post I have provided links to photo albums that I made for each one.

Heading south on 5 September, we split the journey over two days, stopping off at the National Trust’s Dunham Massey west of Manchester, and spending overnight at a Premier Inn in Stoke-on-Trent, only a couple of miles in fact from where I attended high school in the 1960s.

Then, the next day (Saturday), we revisited Dyrham Park (also a National Trust property) in south Gloucestershire a few miles north of Bath , a property we had first visited in August 2016 on a day trip from our former home (until five years ago) in north Worcestershire.

Dunham Massey is an early 17th century mansion, home of the Booth (Earls of Warrington) and Grey families. Lady Mary Booth (1704-72), only daughter of George, the 2nd Earl of Warrington, married her cousin Harry Grey, 4th Earl of Stamford in 1736, and their son George Harry (the 5th earl) inherited the estate, which includes a large deer park and extensive gardens, with the estate passing to the Grey family.

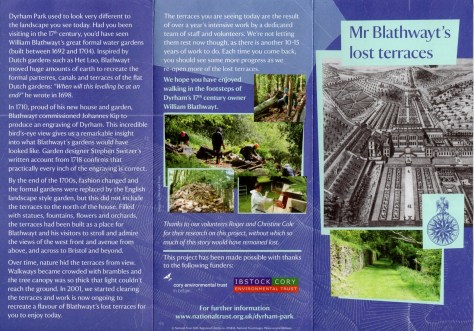

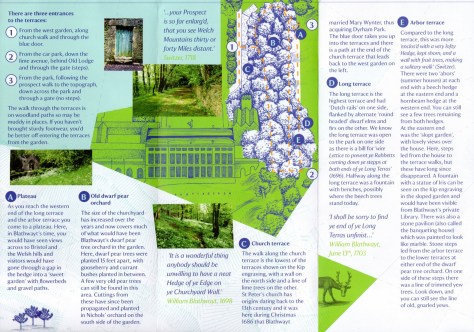

Dyrham Park was created in the 17th century by William Blathwayt, and has strong links to Britain’s colonial and empire past. Since our first visit, the house has undergone some serious refurbishment after the leaking roof was fixed, and we had the impression that there was more on display in the house today than almost 10 years ago.

On the third day (Sunday) we headed east to the outskirts of Salisbury to explore Old Sarum Castle, a hilltop fort that was occupied for at least 5000 years, and where William the Conqueror, post-1066, built a fine Norman Castle. It’s also where the first two Salisbury cathedrals were built, but only the footprint of the second remains. What is particularly striking (apart from the great views over Salisbury and its cathedral spire) is just how much earth was moved to construct the hillfort. The Iron Age ramparts are high and the ditches incredibly deep. Wandering around, there is a deep sense of history over the centuries.

Returning west from Old Sarum we headed to Stourhead that was built on the site of Stourton Manor in Wiltshire from 1717, by Henry Hoare I, son of Sir Richard Hoare who founded a private bank in 1672, now the UK’s oldest private bank and still in the ownership of the Hoare family after 12 generations.

Henry I began construction of a large Palladian mansion, but died before it was completed. It was his son, Henry II (also known as Henry the Magnificent) who made alterations to the fabric of the building, filled it with treasures, and created Stourhead’s world-famous garden.

On Monday we headed northeast into Wiltshire once again to visit Lacock and The Courts Garden. And as I was plotting a route home on Google Maps I discovered that the preferred routed passed within a couple of miles of Farleigh Hungerford Castle, so we made a detour there.

Lacock is a fine country house built on the foundations of a medieval abbey, and is full of the most wonderful treasures. It was the home of 19th century polymath William Henry Fox Talbot (right) one of the inventors of photography, developed through his keen interest in botany. There is an interesting museum at Lacock celebrating Fox Talbot’s work. On reflection, this was one of the best visits of the week. The National Trust also owns most of the houses in Lacock village, and after visiting the Abbey we took a short walk around. As you can see from those photos, it’s no wonder that the village has served as the backdrop for numerous film and TV productions.

Lacock is a fine country house built on the foundations of a medieval abbey, and is full of the most wonderful treasures. It was the home of 19th century polymath William Henry Fox Talbot (right) one of the inventors of photography, developed through his keen interest in botany. There is an interesting museum at Lacock celebrating Fox Talbot’s work. On reflection, this was one of the best visits of the week. The National Trust also owns most of the houses in Lacock village, and after visiting the Abbey we took a short walk around. As you can see from those photos, it’s no wonder that the village has served as the backdrop for numerous film and TV productions.

The Courts Garden in Holt is a delightful English country garden, divided into a number of ‘rooms’. Major Clarence Goff and his wife Lady Cecilie bought The Courts in 1921, developing the garden very much in line with the ideas of renowned horticulturalist Gertrude Jekyll. Major Goff gave The Courts to the National Trust in 1944, but he and his daughter Moya remained life tenants at the property. In the mid-1980s, the Trust began to take a more active role in management of the garden.

Construction of Farleigh Hungerford Castle began around 1380, and it remains one of the most complete surviving in the region. Over the centuries it became an elegant residence, and was lived in until the late 17th century. There is remarkably well-preserved chapel with wall paintings and painted tombs, and another with elegant marble effigies of Sir Edward Hungerford (d. 1648) and his wife Jane.

On Tuesday we headed south, no more than 23 miles from our holiday cottage, to visit three properties close by: Lytes Cary Manor, Tintinhull Garden, and Montacute House.

Lytes Cary Manor dates from the 14th century, but has been added to over the centuries. The Lytes family finally sold the estate in 1755, and it was occupied by numerous tenants subsequently until Sir Walter Jenner and his wife Flora purchased it in 1907. They added a west wing, and designed a garden inspired by the Arts and Crafts Movement. The house was left to the National Trust in 1947, and is filled with their personal possessions.

Tintinhull Garden was the work of two 20th century gardeners, one amateur the other professional, around a 17th century house (not open to the public). The property was bought by Phyllis Reiss and her husband, Capt. F.E. Reiss in 1933. Phyllis died in 1961 and left Tintinhull to the National Trust. Twenty years later renowned gardener Penelope Hobhouse (right) took on the tenancy of Tintinhull and built on Reiss’s earlier garden design.

Tintinhull Garden was the work of two 20th century gardeners, one amateur the other professional, around a 17th century house (not open to the public). The property was bought by Phyllis Reiss and her husband, Capt. F.E. Reiss in 1933. Phyllis died in 1961 and left Tintinhull to the National Trust. Twenty years later renowned gardener Penelope Hobhouse (right) took on the tenancy of Tintinhull and built on Reiss’s earlier garden design.

Montacute House is an elegant Elizabethan Renaissance country house, completed in 1601, and just a few miles from Tintinhull. Only the ground floor is currently open to the public since conservation work is making the stairs and upper floors safe to view. Most of the artefacts and paintings on display have been assembled by the National Trust, and they have been fortunate to acquire many portraits of the Phelips family who built and occupied Montacute. The house is surrounded by extensive gardens. However, we didn’t explore the gardens to any extent since thunderstorms were threatening.

The following day we made the longest excursion (a round trip of 110 miles) to visit Dunster Castle and Cleeve Abbey on the north Somerset coast west of Prestleigh. It was a miserable drive there and back: lots of traffic along narrow and winding trunk roads. But the grandeur of Dunster and the exceptional preservation of Cleeve made up for the driving.

Dunster Castle was originally founded after the Norman conquest of 1066 when William I gave the land to the de Mohun family who built first a timber castle on an earlier Saxon mound, during the Norman pacification of Somerset. Only the 13th century gatehouse remains from the original castle. Much of the medieval castle was demolished at the end the First English Civil War in 1646. Over the centuries Dunster became the elegant country residence of the Luttrell family who had lived there since the mid-14th century, with views over the Bristol Channel and surrounding hills. The family lived at Dunster until 1976 when it passed to the National Trust.

Here is a 5 minute potted history of Dunster Castle.

Cleeve Abbey, just a few miles east of Dunster, was founded in the late 12th century by the Cistercians. It is remarkably well preserved, with many buildings more or less intact. In fact it was acquired by George Luttrell of Dunster Castle in 1870 with the intention of preserving what remained and making it a tourist attraction. Only the footprint of the abbey church remains after the abbey was suppressed in 1536 as part of Henry VIII’s Dissolution of the Monasteries. There is a floor of exquisite 13th century tiles.

On Thursday we headed northwest to explore two National Trust properties southeast of Bristol and north of Weston-Super-Mare.

Tyntesfield is one of the most opulent houses we have visited. Victorian Gothic Revival in design, it was built by William Gibbs (right, 1790-1875) who made a fortune mining and exporting guano (bird poo) from the Chincha Islands off the coast of Peru, about 235 km south of Lima, for use as fertilizer in British agriculture. As they say in Yorkshire, ‘Where’s there’s muck, there’s brass‘ (meaning ‘dirty or unpleasant activities can be lucrative’). The house has an enormous collection of family possessions, more than 70,000 apparently. Opulent as it was, Tyntesfield was a family home. It was bought by the National Trust in 2002 as the house and estate were in danger of being auctioned off piecemeal.

Tyntesfield is one of the most opulent houses we have visited. Victorian Gothic Revival in design, it was built by William Gibbs (right, 1790-1875) who made a fortune mining and exporting guano (bird poo) from the Chincha Islands off the coast of Peru, about 235 km south of Lima, for use as fertilizer in British agriculture. As they say in Yorkshire, ‘Where’s there’s muck, there’s brass‘ (meaning ‘dirty or unpleasant activities can be lucrative’). The house has an enormous collection of family possessions, more than 70,000 apparently. Opulent as it was, Tyntesfield was a family home. It was bought by the National Trust in 2002 as the house and estate were in danger of being auctioned off piecemeal.

A few miles west of Tyntesfield stands Clevedon Court, a mid-14th century manor house and home of the Elton family since 1709. The National Trust owns the buildings, but the family has responsibility for the interiors and possessions. While there are many pieces of furniture and paintings and the like to attract one’s attention (including a collection of rare glass), what particularly grabbed mine was the fabulous collection of studio pottery made in the Sunflower Pottery close by the house by Sir Edmund Elton, the 8th Baronet. I’ll have more to say about this collection in a separate post.

Although not the quickest route back to our cottage, we took a diversion to drive through limestone Cheddar Gorge, somewhere that has been on my bucket list for many years. It’s three miles long and, in places, 400 feet deep. From the number of commercial outlets at the bottom of the Gorge, it’s a location that must receive an overwhelming number of visitors each year.

On our last day, 12 September, we headed east again to Old Wardour Castle, which was built in the 1390s for John, Lord Lovell. It’s an unusual hexagonal castle with a similar courtyard. It was partly demolished in the English Civil Wars in 1644 when Henry, Lord Arundell accidentally detonated a mine. He was the owner of the castle and was attempting to retake it from Parliamentary Forces. In the late 18th century the 8th Lord Arundell abandoned Old Wardour Castle and built a country house, New Wardour Castle, close by which can be seen from the top of the south tower. Much of the castle is accessible, and English Heritage has placed many information boards around the site in addition to a possible audio tour. They constructed a banqueting hall beside the old castle as somewhere to entertain guests visiting the ruin.

And that was the end of our visits. We departed early the following morning (Saturday) for the long haul north to Newcastle, with a couple of stops on the way. It took less than hours, and we were home by mid-afternoon, reflecting on a very enjoyable week in Somerset and Wiltshire, a part of the country that we knew very little about before this trip.

Photo albums:

- Dunham Massey

- Dyrham Park

- Old Sarum Castle

- Stourhead

- Lacock

- The Courts Garden

- Farleigh Hungerford Castle

- Lytes Cary Manor

- Tintinhull Garden

- Montacute House

- Dunster Castle

- Cleeve Abbey

- Tyntesfield

- Clevedon Court

- Old Wardour Castle