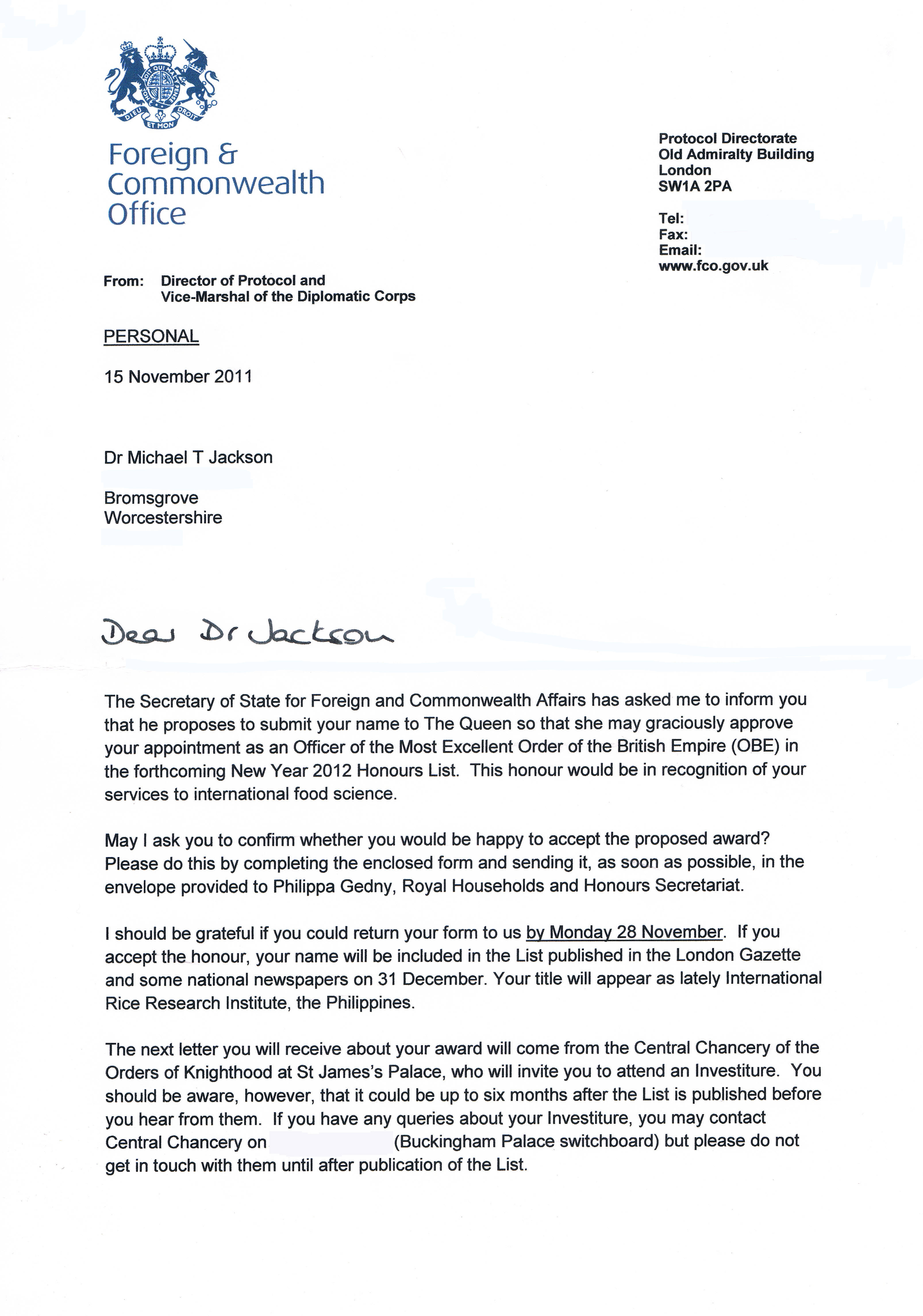

On a bright, sunny day last November (my birthday, actually) I was outside cleaning the car, when the postman passed by. He handed me several envelopes and my immediate reaction was that this was another load of the usual junk mail. So you can imagine my surprise when I came across one that seemed rather official looking. And I was even more surprised when I read what it had to say – that I had been nominated to become an Officer of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, or OBE, for services to international food science. Well, I was gob-smacked, quite emotional really. I rushed inside to tell Steph – who was equally stunned, and we set to ponder how on earth this had come about. I did some Google detective work, and was able to find out a little more about the nomination process, and how successful nominees are chosen. But beyond that, I had no idea. Subsequently (in early January 2012), there was a press release from the British Embassy in the Philippines. There is some more information about the British honours system on the BBC website.

On a bright, sunny day last November (my birthday, actually) I was outside cleaning the car, when the postman passed by. He handed me several envelopes and my immediate reaction was that this was another load of the usual junk mail. So you can imagine my surprise when I came across one that seemed rather official looking. And I was even more surprised when I read what it had to say – that I had been nominated to become an Officer of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, or OBE, for services to international food science. Well, I was gob-smacked, quite emotional really. I rushed inside to tell Steph – who was equally stunned, and we set to ponder how on earth this had come about. I did some Google detective work, and was able to find out a little more about the nomination process, and how successful nominees are chosen. But beyond that, I had no idea. Subsequently (in early January 2012), there was a press release from the British Embassy in the Philippines. There is some more information about the British honours system on the BBC website.

And then began six weeks of purgatory – nominees are sworn to secrecy until the honours list is published officially in The London Gazette, scheduled for 31 December! Anyway, on the 31st I came down for breakfast, and went to the website to see my name in print. And I couldn’t find it! I began to wonder if I had ticked the right box when I sent the form back. But then I found it (page N24) – under the Diplomatic Service and Overseas list. And looking down the list, it was then that I discovered that my good friend and former colleague at IRRI, John Sheehy, had also been made an OBE. A great day for IRRI!

Not long after the New Year, I received a package of information from the Central Chancery of the Orders of Knighthood, with the date of the investiture: 29 February. I applied for tickets – for Steph, daughter Philippa, and my closest colleague in the DPPC at IRRI, Corinta Guerta.

Not long after the New Year, I received a package of information from the Central Chancery of the Orders of Knighthood, with the date of the investiture: 29 February. I applied for tickets – for Steph, daughter Philippa, and my closest colleague in the DPPC at IRRI, Corinta Guerta.

Not long afterwards, the tickets arrived in the mail.

Corinta arrived to the UK on 26 February, and after her meeting at DfID in London on the Monday morning, came up to Bromsgrove to spend a couple of nights with us, and to join us for the investiture. We agreed to meet Philippa in London.

One other issue for me was what to wear: morning dress (top hat and tails) or lounge suit (and even which tie to choose).* I finally settled on my lounge suit and pink tie.

Then came the day of the investiture. It was an early start on the 29th: up at 5 am, and off to Solihull to catch the 7:41 am Chiltern Railways service from Solihull (about 25 minutes from Bromsgrove by car) to London Marylebone. The train eventually was very crowded, with some passengers standing all the way from Banbury to London; but we had good seats. We met up with Philippa at Marylebone, had a quick cup of coffee, and then took a taxi to the Palace.

Security was extremely tight, and we had to show photo IDs and our tickets for access. It’s quite some feeling walking through the gates of the Palace (made in Bromsgrove), past the guards, and through into the inner quadrangle. At the main entrance, under a glass canopy, our tickets were again checked, and we headed inside. What a spectacle: guardsmen in their metal breastplates and equerries in morning suits; everyone was very polite and friendly. After a quick comfort stop, Steph, Philippa, and Corinta headed for the Ballroom, and I headed off in another direction to meet the other honours recipients. The recipients of knighthoods and CBEs were together in one room, the OBEs and MBEs in another. Mineral water and juices were provided – in bottles with The Queen’s crest, and little goblets with EIIR engraved (not to be left on a mantelpiece next to a priceless ceramic vase). We waited in a long gallery full of the most incredible pieces of art – goodness knows what their value was.

One of the Officers on Duty gave a briefing about the ceremony, that it would be held by HRH The Prince of Wales (not HM The Queen, much to my initial disappointment). It began precisely at 11 am, and the first batch of recipients was called away. I was in the second batch. Click on the image below to read the investiture program.

I guess I must have been called to receive my OBE at around 11:15; and afterwards the recipients returned to the back of the ballroom and took their seats to watch the rest of the proceedings. Immediately after the presentation, the insignia was removed and placed in a special case.

I was intrigued to see that the insignia was made by a company based in Bromsgrove, the Worcestershire Medal Service Ltd.

The medals are actually manufactured at a site in Birmingham’s Jewellery Quarter, but the head office is a small shop on one of my daily walk routes!

Head office of Worcestershire Medal Service Ltd. in Bromsgrove.

Anyway, to get back to the ceremony. Each batch of recipients crossed the ballroom at the rear, to enter a corridor on the other side. And it was from there that each recipient was called forward, to wait beside one of the Officers on Duty, and then move forward again as the surname was announced (and the reason for the honour). Turning towards HRH, men gave a small bow from the neck and women a curtsy. The insignia was pinned on, and a few words exchanged.

HRH asked if I was still working in the Philippines – he had been well briefed, and then we spoke briefly about different varieties of rice. Then, after some words of thanks from HRH and a warm handshake that was it – my moment of glory all over, and I exited through a door on the opposite side from where I had entered. The ballroom itself was quite dimly lit, from several huge chandeliers. On the video footage I have seen, and on the close circuit TV that was broadcast to waiting recipients, the ballroom look very bright indeed.

Considering the number of honours recipients and that HRH spoke to each person individually, the investiture was over just after 12 noon. Then we were able to meet up with our guests. Steph, Philippa, and Corinta had found seats at the back of the ballroom. We then made our way outside for picture taking.

Here are just a few, but click on the image immediately below and a web album of the best photographs will open.

Philippa, me, and Steph

Corinta, me, and Steph

Corinta and me

Steph and me outside Buckingham Palace

Unfortunately we were not able to stay long in London, since Corinta was due to fly back to the Philippines from Birmingham Airport (BHX) at 8:30 pm. So, once we had taken all the photographs we wanted, I hailed a taxi (much easier outside the Palace than I had envisaged) and we set off for Marylebone and the train. We had a quick bite to eat at the station, and our train to Solihull departed at 2:37 pm, arriving in Solihull on time just after 4 pm. Corinta had plenty of time to get changed, complete some last minute packing, and even enjoy a cup of tea and some home-made Victoria sponge before heading off to BHX in an Emirates Airlines limo.

Originally we thought about driving to London for the investiture. Hindsight is a wonderful thing. I would have been stupid to have attempted this trip by car, even though we could have parked right inside Buckingham Palace. On the afternoon of 29 February there were serious traffic incidents on one of the main motorways (M40) into London that we would have used, and there were holdups for several hours. So instead of an anticipated stressed journey by car, we let the train take the strain.

As Steph and I reflected on the day over dinner and a cup of tea that same evening, it was quite surreal to think we had been inside Buckingham Palace just a few hours before. But what a privilege it was, and what a fantastic honour to have received in recognition of the work I did in agricultural research, especially the conservation and use of crop genetic resources.

My former staff in the International Rice Genebank at IRRI sent me this photo – a very thoughtful touch.

On 22 May I received my Warrant of Appointment as an Officer of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire. This is printed on parchment, has an embossed Seal of the Order in the top left corner, and measures 11.5 x 16.5 inches approx.

* Over the past year since I first posted this story, lots of other recipients of awards have also worried about what to wear to an investiture, and their web searches have often led to my blog. I hope my advice has been useful. I know in at least one case that it has been, since there are a couple of comments to that effect.

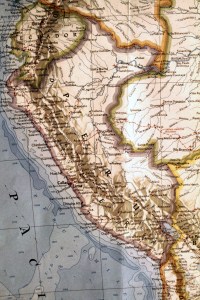

The Andes of South America are the home of the potato that has supported indigenous civilizations for thousands of years. As many as 4,000 native potato varieties are still grown. The region around Lake Titicaca in southern Peru and northern Bolivia is particularly rich in genetic diversity, and the wild potatoes from here are valuable for their disease and pest resistance [1].

The Andes of South America are the home of the potato that has supported indigenous civilizations for thousands of years. As many as 4,000 native potato varieties are still grown. The region around Lake Titicaca in southern Peru and northern Bolivia is particularly rich in genetic diversity, and the wild potatoes from here are valuable for their disease and pest resistance [1]. I joined CIP in January 1973 as Associate Taxonomist, charged with the task of collecting potato varieties and helping them to maintain the large germplasm collection, that grew to at least 15,000 separate entries (or clonal accessions), but was reduced to a more manageable number through the elimination of duplicate samples. The germplasm collection was planted each year from October through April, coinciding with the most abundant rains, in the field in Huancayo, central Peru at an altitude of more than 3,100 meters.

I joined CIP in January 1973 as Associate Taxonomist, charged with the task of collecting potato varieties and helping them to maintain the large germplasm collection, that grew to at least 15,000 separate entries (or clonal accessions), but was reduced to a more manageable number through the elimination of duplicate samples. The germplasm collection was planted each year from October through April, coinciding with the most abundant rains, in the field in Huancayo, central Peru at an altitude of more than 3,100 meters.

that endeavour. In May 1973 I joined my colleague Zosimo Huaman (left) to collect potatoes in the Departments of Ancash and La Libertad, to the north of Lima. The highest mountains in Peru are found in Ancash, and our route took us through into the

that endeavour. In May 1973 I joined my colleague Zosimo Huaman (left) to collect potatoes in the Departments of Ancash and La Libertad, to the north of Lima. The highest mountains in Peru are found in Ancash, and our route took us through into the

of a minor Andean tuber crop called oca (Oxalis tuberosa). We went to the village of Cuyo Cuyo, more than 100 km north of Puno in southern Peru. Dropping down from the altiplano, the road hugs the sides of the valley, and is often blocked by landslides (a very common occurrence throughout Peru in the rainy season). Along the way – and due to the warmer air rising from the selva (jungle) to the east – the vegetation is quite luxurious in places, as the white begonia below shows (the flowers were about 8 cm in diameter). Eventually the valley opens out, with terraces on all sides. These terraces (or andenes) are ancient structures constructed by the Incas to make the valley more productive.

of a minor Andean tuber crop called oca (Oxalis tuberosa). We went to the village of Cuyo Cuyo, more than 100 km north of Puno in southern Peru. Dropping down from the altiplano, the road hugs the sides of the valley, and is often blocked by landslides (a very common occurrence throughout Peru in the rainy season). Along the way – and due to the warmer air rising from the selva (jungle) to the east – the vegetation is quite luxurious in places, as the white begonia below shows (the flowers were about 8 cm in diameter). Eventually the valley opens out, with terraces on all sides. These terraces (or andenes) are ancient structures constructed by the Incas to make the valley more productive.

During the late 1980s, when I was on the faculty of the University of Birmingham, my colleague, Brian Ford-Lloyd (now Emeritus Professor of Conservation Genetics) and I had a research grant from United Biscuits to work on somaclonal variation in potatoes. Whatever is that? I hear you cry. Well, it’s technique to grow plants from small pieces of plant tissue on sterile nutrient agar (a jelly-like substance), and try and bring about genetic changes which are primarily due to disorganized tissue growth and chromosome changes. The plants thus produced are called somaclones. And our aim was to produce a somaclonal variant of the potato variety Record, which was at that time, one of the most important varieties for producing potato crisps (chips in American parlance).

During the late 1980s, when I was on the faculty of the University of Birmingham, my colleague, Brian Ford-Lloyd (now Emeritus Professor of Conservation Genetics) and I had a research grant from United Biscuits to work on somaclonal variation in potatoes. Whatever is that? I hear you cry. Well, it’s technique to grow plants from small pieces of plant tissue on sterile nutrient agar (a jelly-like substance), and try and bring about genetic changes which are primarily due to disorganized tissue growth and chromosome changes. The plants thus produced are called somaclones. And our aim was to produce a somaclonal variant of the potato variety Record, which was at that time, one of the most important varieties for producing potato crisps (chips in American parlance).