At breakfast earlier last week, Steph and I were comparing this past winter to the other three we have experienced since moving to the northeast in October 2020. It’s not that it has been particularly cold. Far from it. But, has it been wet!

It feels as though it hasn’t stopped raining since the beginning of the year. The ground is sodden. And as for getting out and about that we enjoy so much, there have been few days. Apart, that is, from local walks when it hasn’t been raining cats and dogs.

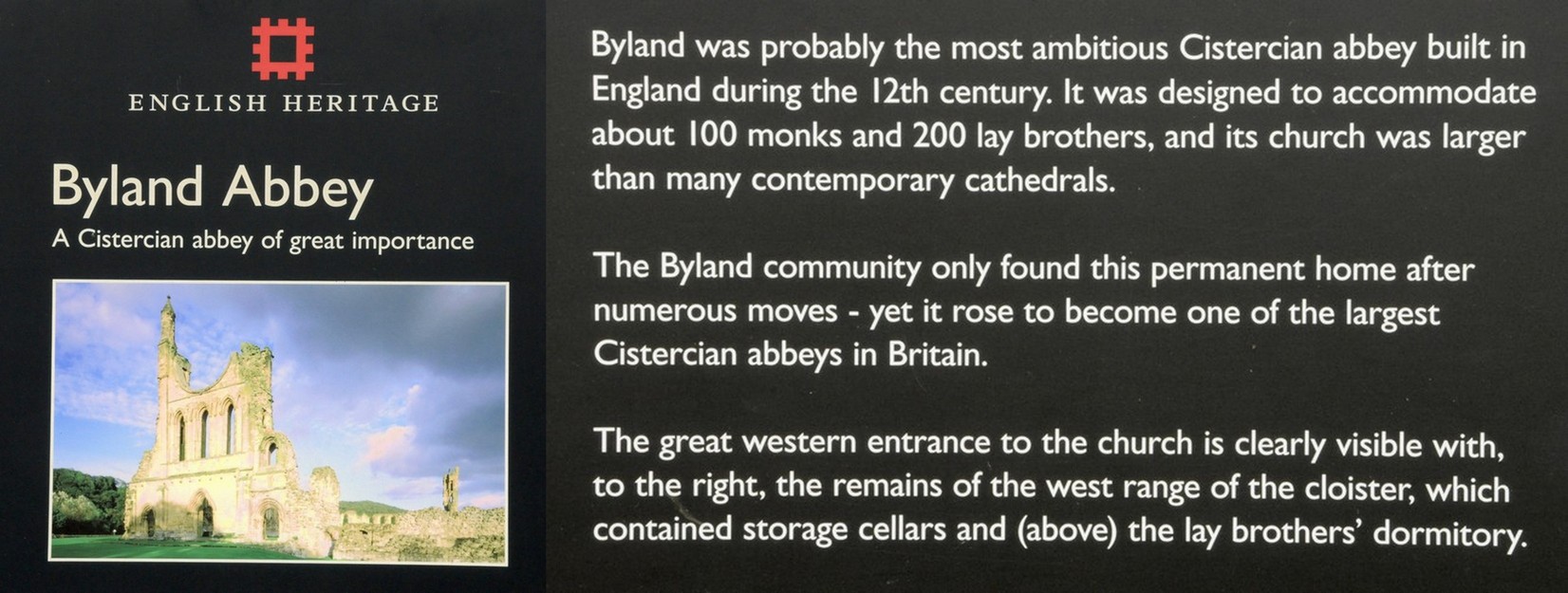

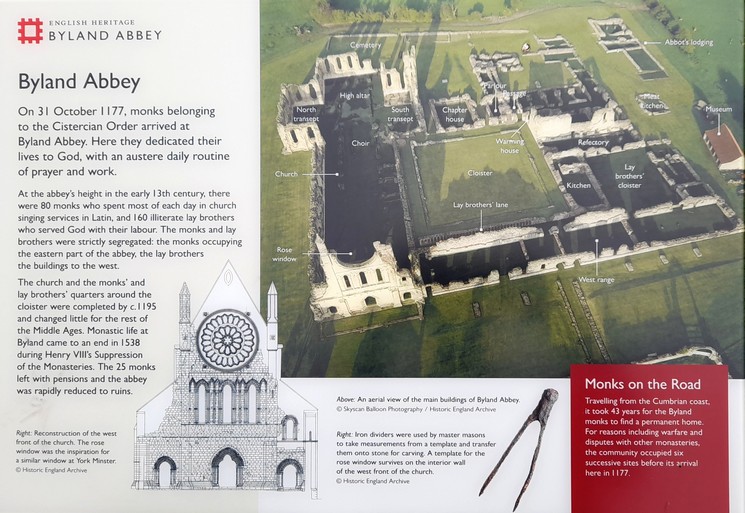

So, with a promising weather forecast for last Friday we made plans for an excursion, heading south around 70 miles into North Yorkshire to visit Byland Abbey, built by a Cistercian community in the 12th century, below the escarpment of the North York Moors.

It’s 12th Cistercian neighbours—less ruined, and arguably more famous—Rievaulx Abbey and Fountains Abbey, stand just 4 miles north as the crow flies and 18 miles southwest, respectively from Byland Abbey.

We decided to take in a couple of other sites on our way south, stopping off at Mount Grace Priory for a welcome cup of coffee and a wander round the gardens, and then—just a few miles further on—the small 12/13th century church of St Mary the Virgin, beside the A19 trunk road that we have passed numerous times, but never taken the opportunity to visit.

St Mary’s was once the parish church of a medieval village, Leake, now disappeared. Nowadays it serves the communities of Borrowby and Knayton. The tower is the earliest remaining structure, and the church has been added to over the centuries (floor plan).

There is a very large graveyard, still in use today, clearly shown in this drone footage.

Then it was on to Byland, taking the cross country route from the A19. And along the way, I saw my first ever hare (and nearly killed, which you’ll see at 02’22 ” in the video below). This route takes you through the delightful village of Coxwold.

Byland Abbey is mightily impressive, even though it’s a shell compared to Rievaulx, for example. But I had the impression that it was much larger than Rievaulx, and it must have been magnificent in its heyday. Its foundation was far from straightforward, and it took the monks more than 40 years before settling on the site at Byland.

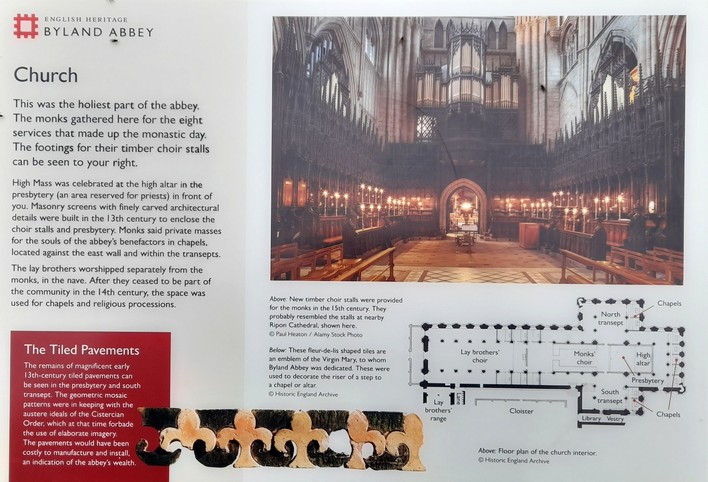

Its west entrance is simply a wall, with the remains of what must have once been an incredible rose window. We saw a note on the English Heritage hut (closed on our visit) that there was a template for the window on the inside of the West Wall, but we couldn’t find it.

And from the entrance there is a view straight down the length of the church towards the North and South Transepts and the High Altar. Just the north wall is still standing, mostly. And when I look at ruins like Byland, I am just in awe of the craftsmanship that it took to build a church like this, with such beautifully dressed stone. I wonder how big a workforce was needed for the construction over the 25+ years it is estimated it took to complete the abbey?

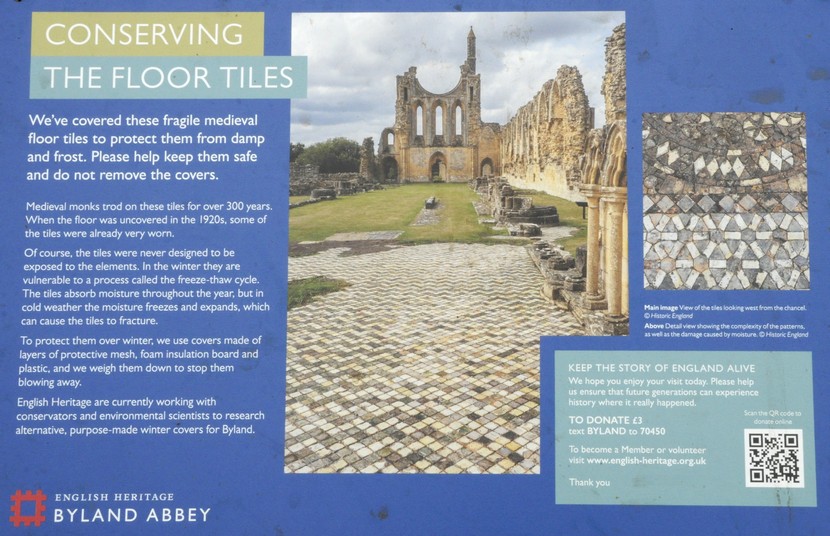

At various locations around the ruins, and especially around the site of the high altar, ceramic floor tiles uncovered during excavations are currently not on view, but protected by tarpaulins.

Like all the other religious houses across the nation, Byland was closed during the Suppression of the Monasteries by King Henry VIII in 1538 and rapidly became a ruin. You can read an excellent history of the abbey on the English Heritage website.

You can view my photo album of Byland Abbey images (and from St Mary’s, Leake) here.

Leaving Byland Abbey, we headed up the escarpment on Wass Bank, stopped off to view the Kilburn White Horse again before heading down the precipitous 1:4 (25%) incline that is the infamous Sutton Bank.

The Kilburn White Horse can be seen for miles around, primarily from the southwest. It was supposedly constructed by a local schoolmaster, John Hodgson and his pupils in 1857. It covers an area of 6475 m² (or 1.6 acres). We had only seen it previously from a distance, or from the car park immediately below. This time we took the footpath at the top of the cliff, emerging near the horse’s ears. The walk from where we parked the car (alongside the glider field) took less than 10 minutes.

And although there wasn’t a good view of the horse per se from the path, the view south over the Vale of York was magnificent. We could see for at least 30 miles over a 200° panorama.

That’s the horse’s eye in the foreground.

A wealthy cloth merchant,

A wealthy cloth merchant,