A topical story in the Lima press

Overnight, there was an interesting and topical post (as far as I’m concerned) on the Facebook page of one of my ‘friends’—the son of one of my graduate students when I was a faculty member at The University of Birmingham in the 1980s. He hails from Peru. Carlos Arbizu Jr. is studying for his PhD at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and, as far as I can determine, he’s working on carrot genetics under the supervision of my friend and former potato scientist David Spooner.

Carlos had posted a link to an article published on the website of the Lima-based Newspaper Perú21: ¿Por qué estudiar un doctorado? (Why study for a PhD?). To which Carlos had added the byline: PhD = Permanent Head Damage.

Maybe he’s going through a difficult patch right now. I’ve seen from several of his posts that he’s immersed in some pretty ‘heavy’ molecular genetic analysis. It’s beyond my comprehension.

But all PhD students go through peaks and troughs. I know I did. Some days nothing can go wrong, progress is swift. The world is your oyster, and there really is a light at the end of the tunnel. On other days, you just wish the earth would open up and swallow you.

And for many PhD students, the most trying time often comes when they begin to draft their thesis and eventually prepare to defend it. Unfortunately many science graduates have received very little formal training in how to write clear and concise prose. Writing just doesn’t come naturally. So what should be one of the most important aspects of completing a PhD can become a long and tedious chore. And before submission regulations were tightened up at UK universities, some students could take a couple of years or more to write up and submit their thesis for examination.

40 years ago today

Well, this Perú21 article was published yesterday. And today, 23 October (if memory serves me right) is exactly 40 years since I defended my PhD thesis: The Evolutionary Significance of the Triploid Cultivated Potato, Solanum x chaucha Juz. et Buk. I was almost 27 (old by UK standards, average or maybe young compared to many US graduate students), and had been working on my degree for four years. I’d completed a one-year MSc degree in genetic resources at Birmingham in September 1971 (having graduated from the University of Southampton with a BSc in botany and geography in July 1970), and then been offered the opportunity to work in Peru for a year at the newly-established International Potato Center (CIP). Well, for various reasons, and to cut a long story short, That opportunity didn’t materialize in September 1971 so my head of department, Professor Jack Hawkes (who went on to supervise my PhD) persuaded the Overseas Development Administration (now Department for International Development, DfID) to cough up some support until the funding for my position at CIP was guaranteed. Thus I began my study in Birmingham, and finally moved to Lima in January 1973, working as an Associate Taxonomist and conducting research that went towards my PhD thesis. And since I was employed and having a regular income, I took another three years to complete all the experimental work I had planned. In any case, when I joined CIP in 1973 the institute was still establishing and developing its own infrastructure. That was also one of the exciting aspects to my work. It was a real opportunity to build up and curate a large collection of Andean potato varieties and wild species, and study them in their native environment.

The CIP field collection of potato varieties planted in the Mantaro Valley near Huancayo in central Peru.

The diversity of Andean potato varieties.

The next couple of photos show some of the field work I carried out in various parts of Peru.

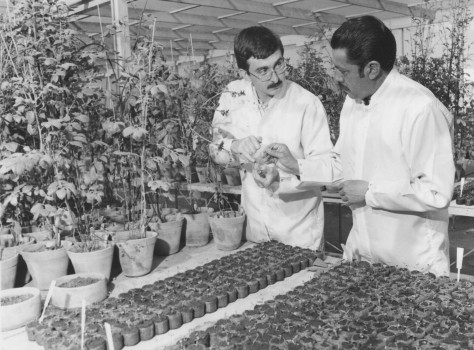

Learning from my supervisor, Professor Jack Hawkes, during one of his visits to Peru while I was carrying out my study.

With CIP taxonomist, Professor Carlos Ochoa, a renowned Peruvian expert on potatoes and their wild relatives.

I was looking at the relationship between potato varieties with different chromosome numbers, so-called diploids and tetraploids, with 24 and 48 chromosomes respectively. If you can cross these two types you expect to produce some with an intermediate chromosome number. So, 48 x 24 = 36, the triploids. For the first years at CIP we didn’t have any glasshouses where we could work. Instead we had rather rustic polytunnels right in the field next to the germplasm collection, where I would make all those pollinations using the so-called cut-stem technique.

Experimental data from other parts of the world had shown that triploids were formed only rarely in such crosses. Yet triploid varieties were quite common and highly prized by potato farmers in the Andes. I was trying to determine if the crossability relationships of these native potatoes might be different in their indigenous environment. So I went on to make hundreds of crosses (and thousands of pollinations), as well as study indigenous farming systems in the south of Peru. This next gallery show some of the triploids potatoes grown by farmers. One of the most prized was the variety Huayro, and there were two forms, one round and the other elongated (and quite large). Both had red skins and yellow flesh.

Back to Birmingham

In May 1975, Steph and I headed back to the UK. But not directly. On the assumption that I would successfully defend my PhD thesis, CIP’s Director General had offered me a new position in the Outreach Department, and with the possibility of moving to Central America. So we headed for Costa Rica (where I’d eventually move to in April 1976) to see the lie of the land, so to speak. And from there we went on to Mexico for a few days to visit our old friends, and former CIP colleagues, John and Marion Vessey who had moved to maize and wheat center, CIMMYT, near Mexico City. From Mexico we headed to New York (first flight on a wide-bodied jet, an Eastern Airlines L-1011 Tristar) for a connection with British Airways to Manchester where my parents met us. We spent a further week looking for somewhere to live in Birmingham, and were fortunate to find an apartment very convenient to the university and only a few minutes walk from the Department of Botany (as it was then) Winterbourne Gardens where I had been assigned some lab space and a desk.

A nightmare waiting to happen

Now remember, there were no PCs or laptops, cloud computing, USB sticks or floppy disks in 1975. All my thesis data was available in hard copy only, and I carried a briefcase with four years of work with me from Lima to the UK on that journey I just related. The briefcase was hardly ever out of my sight! In those days it was not unknown for a graduate student to have lost a briefcase on a journey containing a complete draft of a thesis. No backup!

Getting into a routine

Once settled in Birmingham, I planned out my work for the coming months, with a deadline of 1 October. That was the final day of submission if I wanted to have my thesis examines and (if approved) have the degree awarded at the next congregation or commencement in early December that same year. But by the beginning of June I had not even begun to write, never mind complete the last minute field experiment I had planned (checking the ploidy of a set of hybrids produced earlier in the year) or create the figures I would include. Again, there was no digital technology available. I had to hand draw all my maps and other figures (my geography training in cartography at Southampton finally came in useful). While the department’s chief technician actually photographed all of these, I had to print all my own photographs (again, the experience I’d gained from my father, a professional photographer all his life, came in handy).

Working to a regular schedule every day, from around 7:30 am until 5 pm with a break for lunch, and spending another couple of hours after dinner, I soon began to make progress, although I didn’t actually start putting pen to paper until the beginning of July. It took me only six weeks to draft my thesis. Once I’d completed a chapter I’d hand it over to Jack Hawkes for review and revision. And to give him credit, he usually handed me back my draft with his comments within a couple of days only (and this was an approach I adopted with all my graduate students during the 1980s).

So, by mid-August or so I had a completed text, I’d checked the chromosome numbers of the hundred or so plants in the field, and set about the figures. I found someone who would type my thesis, but at the last moment he had to use a manual typewriter since the electric one he’d wanted to rent was no longer available. In 1975 The University of Birmingham changed the thesis submission regulations and it was no longer necessary to submit a thesis fully bound in a hard cover. I was able to submit in temporary binding, and this in fact saved perhaps three weeks from my tight schedule. I hit the 1 October deadline with about twenty minutes to spare just before 5 pm.

Thesis defence

I was quite surprised when my external examiner planned the defence of my thesis just three weeks later. All went to plan. In those days, the exam consisted of the graduate student, the external examiner and an internal examiner (usually the thesis supervisor). Today things might have changed, and even when I worked at Birmingham in the 80s the supervisor was no longer permitted to act as the internal examiner. I believe there may now also be a third panel member, to see fair play.

From the outset it was apparent that my thesis would pass muster, since the external examiner told me that he’d enjoyed reading the thesis. But we then went on to have a thorough discussion over the next three hours about many of the details, and the implications for potato genetic conservation and breeding. Phew!

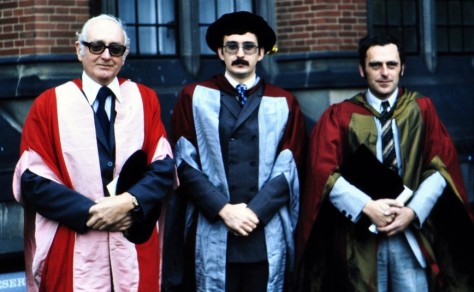

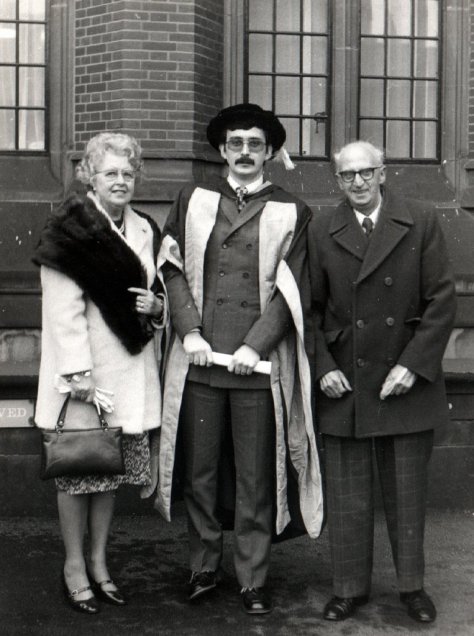

And in early December, the 12th actually, I was able to celebrate with others from the department as we were awarded our degrees at the mid-year congregation.

L to R: Pam Haigh, Brenig Garrett, me, Prof Trevor Williams, Prof Jack Hawkes, Dr Jean Hanson, Margaret Yarwood, Jane Toll, Stephen Smith

With my PhD supervisor, Prof. Jack Hawkes on my right, and MSc supervisor, Prof. Trevor Williams on my left; 12 December 1975.

Was it worth it?

So let me come back to the question I posed in the title of this post. Was it worth it? Unequivocally Yes! Would I want to do it again? No!

Actually completing a PhD is probably the most selfish piece of research that a scientist will ever get to do. There’s one aim: complete a thesis and have the doctorate awarded. PhD research does not have to be ground-breaking at all. In fact much of it is pretty mundane, and that’s one of the down sides when things are not going so well. For Birmingham at least, the PhD regulations stated that the thesis had to represent a piece of original research, completed under supervision. And it’s the ‘under supervision’ that is critical. A PhD student is still maturing, so to speak. The work is guided by a mentor. Of course there can be breakthroughs that lead to the most prestigious prizes. I believe that Sir Paul Nurse’s PhD research set him off on the path that eventually led to his Nobel prize.

I have encouraged others to research for a PhD, and I hope I was able to give them the support and advice that my supervisors gave me. In that respect my PhD was a positive experience. It’s not always the case, and when student-supervisor relationships break down, every one suffers. It does not necessarily have to take many, many months (or years even) to write a thesis. It takes self-discipline but also support from the supervisor.

Without a PhD I would not have enjoyed the career in international agricultural research and academia that I did. My PhD was like a ‘union card’. It enabled me to seek opportunities that would probably have been closed without a PhD. But I also acknowledge that I was lucky. I moved into a field—genetic resources—that was just expanding, as were the international centers of the CGIAR. And I had mentors who were prepared to back me.

Forty years on I can look back to those days in 1975 with a fair degree of nostalgia. And then reflect on the benefits that accrued from that intense but disciplined period in the summer of 1975 (when there was a heat wave, and Arthur Ashe won the men’s title at Wimbledon), and which allow me now to enjoy the retirement I started five years ago.

Both of our daughters, Hannah and Philippa, went on to complete a PhD (in 2006 and 2010, respectively) in their chosen field: psychology! So I can’t have passed on so many negative vibes about graduate study, although their choice of psychology does make a profound statement, perhaps.

Peer-reviewed papers

Incidentally, I finally got around to publishing three papers from my thesis. When I returned to CIP just before New Year 1976, I moved into a new role and responsibilities. And even though I eventually found time to draft manuscripts, these took some time to appear in print after peer review, revision and acceptance. One of the papers—on the field work at Cuyo Cuyo—was originally submitted to the journal Economic Botany. And there it languished for over two years. I received an invitation from the editor of Euphytica to submit a paper on the same topic, so I withdrew my manuscript from Economic Botany. About that same time I received a letter from that journal’s interim editor in chief that manuscripts had been discovered unpublished up to 20 years after they had been submitted, and what did I want to happen to mine. It was published in Euphytica in 1980.

Jackson, M.T., J.G. Hawkes & P.R. Rowe, 1977. The nature of Solanum x chaucha Juz. et Buk., a triploid cultivated potato of the South American Andes. Euphytica 26, 775-783. PDF

Jackson, M.T., J.G. Hawkes & P.R. Rowe, 1980. An ethnobotanical field study of primitive potato varieties in Peru. Euphytica 29, 107-113. PDF

Jackson, M.T., P.R. Rowe & J.G. Hawkes, 1978. Crossability relationships of Andean potato varieties of three ploidy levels. Euphytica 27, 541-551.PDF

What a great post, Dr. Jackson! It is always useful to know how PhDs were achieved in the past. I cannot imagine living without backing up my research information now. Actually, I have to do it weekly. Now we need even better computers and programs to analyze DNA data.

Writing is very important and I think the most tedious part is to make the decision to sit down and start writing. Fortunately, the Writing Center at UW-Madison offers workshops and support that are very useful.

On the other hand, I love my PhD studies and UW-Madison offers me an incredible atmosphere. I feel so lucky to be working with a great team here on the carrot genetics using very modern techniques. So far, together with my academic advisor, Dr. Spooner, we published two peer-reviewed papers, and two more are under review now. Hopefully, we will finish the draft of two more papers before the year comes to an end.

Finally, I like the format that was used by journals in the past. I believe PLoS ONE is using a similar format nowadays. Cool!

Thank you for sharing this post.

All my best,

Carlos I. Arbizu Jr.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on #iblogstats and commented:

Love this! This author should write a book. Thank you! I remember reading these, mainly because my mom locked up all other books. What you have researched may hold some great answers to questions in potato farming! Polyploidy had always intrigued me.

LikeLike