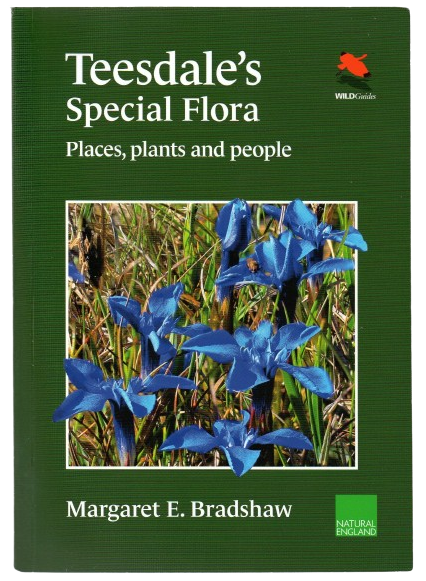

Just yesterday, I heard that an old friend of almost 50 years (who was a colleague of mine—supervisor, actually—at the International Potato Center in Lima, Peru) had died recently, just shy of his 96th birthday.

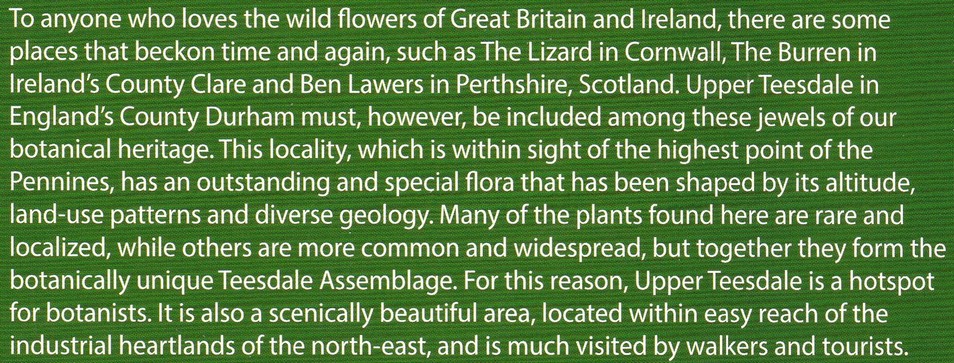

Ken Brown with potato researchers in East Africa, discussing diffuse light storage of seed tubers.

Ken Brown and I first met in February 1976 when he joined the center (known by its Spanish acronym CIP) as Coordinator for Regional Research and Training in the Outreach Program (shortly afterwards renamed Regional Research and Training).

Ken Brown and I first met in February 1976 when he joined the center (known by its Spanish acronym CIP) as Coordinator for Regional Research and Training in the Outreach Program (shortly afterwards renamed Regional Research and Training).

I had returned to Peru at the end of December 1975, having just been awarded my PhD at the University of Birmingham, and was waiting for an assignment as a postdoc in Outreach (moving to Costa Rica in April 1976). My wife Steph and I were living in CIP’s guesthouse in La Molina, and as far as I can recall we were the only residents apart from the ‘wardens’, Professor Norman Thompson and his wife Shona, who were at CIP on a one-year sabbatical from a university in the USA (Michigan State I believe).

Until, one morning when we went into breakfast, and the Browns (Ken, his wife Geraldine, and five sons: Sean, James, Donal, and twins Ronan and Aidan) were already at the table, having arrived during the night.

L-R: Geraldine Brown, Steph, Josianne and Roger Cortbaoui (who joined CIP after the Browns had arrived), and Ken with Aidan on his knee.

Ken and I hit it off immediately. He had a wicked sense of humour. Throughout the years I worked alongside him, he was extremely supportive of all his staff, managing them and his program on a ‘loose rein’, never second-guessing or micro-managing. I learnt a lot about program and staff management from Ken. The Spanish term simpático sums up Ken to a tee.

Originally a cotton specialist (in plant physiology if my memory serves me correct), Ken had worked in Africa (where he met Geraldine), and immediately prior to joining CIP had been based at Lyallpur (now Faisalabad) in the Punjab region of Pakistan. He had an undergraduate degree from the University in Reading, and was awarded a PhD in 1969 after being persuaded by Professor Hugh Bunting (who held the chair in agricultural botany) to submit his publications for the degree.

In 1976 the head of the Outreach Program was American Richard ‘Dick’ Wurster. After he left CIP in 1978, Ken stepped up to become head of Regional Research. It was then that I also became CIP’s Regional Representative for Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean (Region II) after the previous regional leader, Ing. Oscar Hidalgo (who passed away under a month ago) left his position in Mexico to pursue PhD studies at the North Carolina State University in Raleigh.

In April 1978, Ken was a member of the team that launched a major regional program in Central America and the Caribbean, perhaps the first consortium among the centers of the CGIAR (the organization that supports a network of international agricultural centers around the world, including CIP).

In April 1978, Ken was a member of the team that launched a major regional program in Central America and the Caribbean, perhaps the first consortium among the centers of the CGIAR (the organization that supports a network of international agricultural centers around the world, including CIP).

Known as PRECODEPA, the program was funded by the Swiss government, and the launch meeting was held in Guatemala City.

At the launch meeting of PRECODEPA in Guatemala City. L-R around the table: Ken Brown, me, CIP Director General Richard Sawyer, CIP senior consultant John Niederhauser, Ing. Carlos Crisostomo (Guatemala), and a representative from Honduras.

In the first months at CIP, the Browns remained in the CIP guesthouse until they found a house to rent or purchase, so I got to know them very well. It was on one of our trips to one of CIP’s research stations at San Ramon that Ken and I had many hours travel to discuss a whole slew of topics.

Ken learning, for the first time, about late blight of potatoes in the field at San Ramon from plant pathologist Ing. Liliam Gutarra.

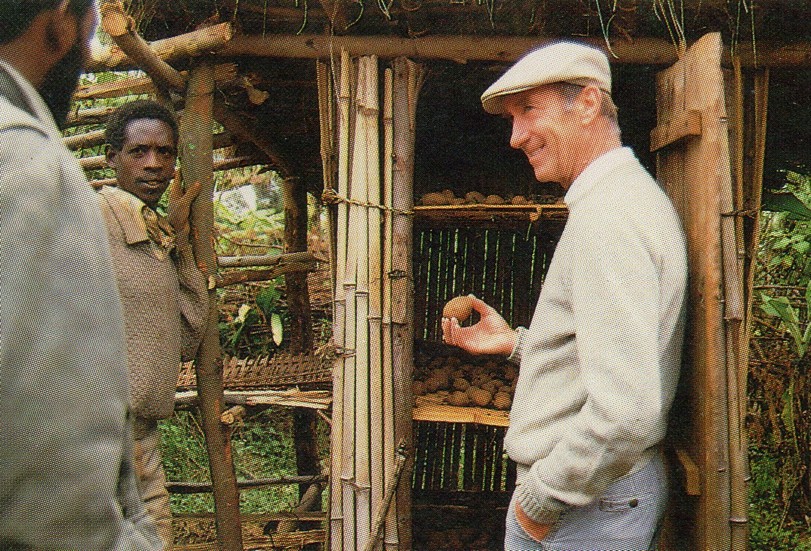

Not long after Ken arrived to Lima, there was a party at the home of CIP’s Director General, Richard Sawyer, to celebrate his birthday. Richard’s wife Norma had chosen a Roman theme for the party. And even though we were staying in the guesthouse, without easy access to costume accessories, Ken and I did our best to look the part, seen in this photo chatting (in Latin?) with Norm Thompson.

Ken remained at CIP until his retirement around 1993 when he published a short memoir: Roots and Tubers Galore: The Story of CIP’s Global Research Program and the People Who Shaped It.

Ken remained at CIP until his retirement around 1993 when he published a short memoir: Roots and Tubers Galore: The Story of CIP’s Global Research Program and the People Who Shaped It.

In a postscript, Ken wrote: I wrote this short account of the Regional [Research] Program not just to record part of CIP’s history, but also to provide some diversion from the usual round of reports and technical publications that are always dropping on your desks. Working with the Regions is enjoyable, and I hope that those of you who did participate during the early years will find these notes of interest. As all who know me are aware, I enjoy the humorous side of life as well as the serious aspects, so if I have been too free with my memories please accept my apologies. To all of you who are part of this story I want to say thank you and wish you every success in the coming years.

I am proud to have been part of that story, and to count Ken among my friends.

However, he was perhaps too free with one memory, about an incident that happened before he even joined CIP, and of which I have no recollection whatsoever. It seems that it forms part of the CIP history.

Between 1973 and 1975, I was an Associate Taxonomist, while also completing the research for my PhD.

But as I read this, I can’t deny that it is something I would be inclined to have done. I wouldn’t put it past me.

After retiring from CIP Ken and Geraldine set up home in Devon. Geraldine sadly passed away a few years back and Ken moved to Cheltenham to live with one of the twins, Aidan and his family.

After I heard that Ken had died, I contacted Donal who I had met several times during the course of our respective careers in international agricultural development. He told me that his father had “lived life to the full until the end and while his body got weaker his mind stayed very alert. He had a very happy and fulfilling life and final years and the end was quick, peaceful and painless – what more could one ask for.”

Indeed it was a life well lived.

Thanks for everything, Ken.

Ken’s funeral was held in Salisbury, Wiltshire on Tuesday 30 July at 3 pm, where he had moved into a retirement home a year or so back.

Ken’s funeral was held in Salisbury, Wiltshire on Tuesday 30 July at 3 pm, where he had moved into a retirement home a year or so back.

I attended his funeral online, and asked Donal for a copy of the Order of Service, which he has given me permission to post here. Click on the image to open a copy.

Ken’s coffin was carried into the crematorium chapel by his five sons to the strains of El Condor Pasa, a very fitting choice given Ken’s many years at the helm of Regional Research and Training at CIP in Peru.

One thing I learned about Ken that I hadn’t known before was his enthusiasm for reggae music, particularly by Bob Marley and The Wailers.

The funeral service concluded with the playing of Three Little Birds by Bob Marley as everyone left the chapel.

Don’t worry about a thing

‘Cause every little thing is gonna be alright

What we hadn’t done, until last week, was explore the hills southwest of Newcastle in the

What we hadn’t done, until last week, was explore the hills southwest of Newcastle in the

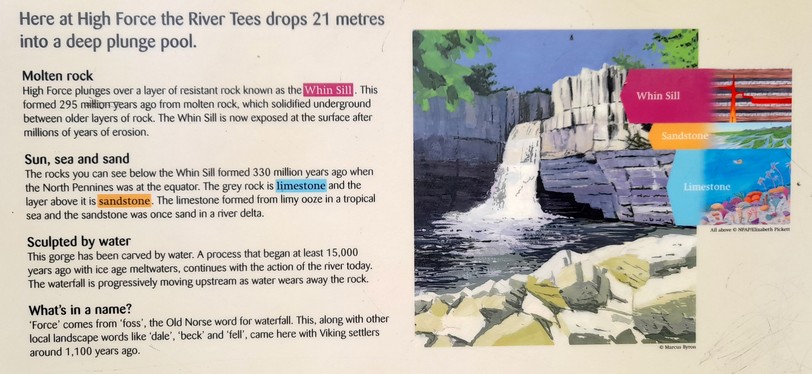

I was quite unaware of the waterfall’s existence until fairly recently, when I read a crime novel by Northumberland-born author

I was quite unaware of the waterfall’s existence until fairly recently, when I read a crime novel by Northumberland-born author