For the past couple of months I’ve delved into Roman military fiction by British authors Simon Scarrow and Harry Sidebottom. Several of their books are set on the fringes of the Roman empire, including references to the conquest and settlement of the British Isles two millennia ago.

For the past couple of months I’ve delved into Roman military fiction by British authors Simon Scarrow and Harry Sidebottom. Several of their books are set on the fringes of the Roman empire, including references to the conquest and settlement of the British Isles two millennia ago.

I’ve been to Rome more times than I can remember, always in a work capacity. Having said that, I often tried to time my arrival in Rome to give me a free weekend to explore the city, mostly on foot. Rome is a great city for walking around. History and archaeology are everywhere. And it has never ceased to amaze me just how Rome was, for hundreds of years, the hub of one of the world’s largest and most powerful empires.

Here are just a few views of ancient Rome, from the Circus Maximus, the Palatine Hill, the Arch of Constantine, the Via Sacra, the Colosseum, and the Pantheon.

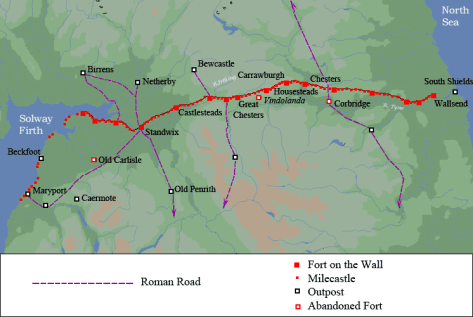

Throughout England, less so in Wales and Scotland, the reminders of Roman occupation can be seen everywhere, from the towns they founded such as Londinium (London), Camulodunum (Colchester), Corinium (Cirencester); the roads they built (still evidenced today in several important highways such as Ermine Street and Watling Street, to name just two), the villas they left behind (such as Fishbourne Palace in West Sussex or Chedworth in Gloucestershire), the various garrison towns like Viriconium (Wroxeter) in Shropshire and Vindolanda in Northumberland, and last but not least, perhaps the most famous landmark of all: Hadrian’s Wall stretching more than 70 miles from coast to coast across northern England.

The Romans did venture further north into Scotland, and built the Antonine Wall from the Clyde in the west to the Forth in the east. Construction began around AD142, but it was abandoned after only eight years. And so Hadrian’s Wall became the de facto northern boundary of the Roman occupation of Britain: Roman territory to the south, land of the barbarians to the north.

Steph is standing astride the north gate entrance at Chesters Roman Fort on Hadrian’s Wall: barbarians to the north (left foot), Romans to the south (right foot).

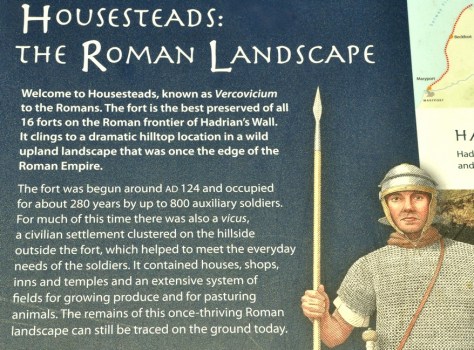

Our outing at the end of June took in two sites along Hadrian’s Wall: Chesters Roman Fort near Chollerford (map) and a little further west, Housesteads Roman Fort, one of the best examples of an auxiliary fort anywhere in Europe. And, between the two, and beside the invisible remains of Carrawburgh Fort (also know as Brocolita), stand the ruins of the small Temple of Mithras. All sites are maintained by English Heritage. We’ve been to Housesteads and the Temple at least twice before, but this was our first visit to Chesters. We weren’t disappointed.

Much of our understanding of the history and archaeology of Hadrian’s Wall is down to one man in the nineteenth century: John Clayton (1792-1890), the town clerk of Newcastle upon Tyne. He came from a wealthy family, acquired much of the land on which the Wall and other sites stand, and over a fifty year period beginning in 1840, he excavated much of what we see today (with the exception of Vindolanda where there is an active excavation and many remarkable finds still being unearthed). Many of the best pieces are now displayed in a museum named after Clayton that was opened by his family in 1896 after his death.

Much of our understanding of the history and archaeology of Hadrian’s Wall is down to one man in the nineteenth century: John Clayton (1792-1890), the town clerk of Newcastle upon Tyne. He came from a wealthy family, acquired much of the land on which the Wall and other sites stand, and over a fifty year period beginning in 1840, he excavated much of what we see today (with the exception of Vindolanda where there is an active excavation and many remarkable finds still being unearthed). Many of the best pieces are now displayed in a museum named after Clayton that was opened by his family in 1896 after his death.

Chesters Roman Fort

Chesters Roman Fort

As with many Roman sites, only the outline of buildings can be seen, just a few feet high. Nevertheless, it’s possible to take in just what the site might have looked like in its heyday. And English Heritage kindly provides reconstructions of what the buildings and overall site might have looked like on display boards around the site—as they do at Housesteads and elsewhere.

We entered through the North Gate, and immediately made our way to baths on the east side of the fort, where the land slopes down to the North Tyne river. The Romans certainly knew how to choose the right spots to build their forts. But at this point the river was easily fordable, and a bridge (no longer standing) was built across the river to connect with Hadrian’s Wall on both banks.

Valley of the North Tyne at Chesters Roman Fort

Remains of Hadrian’s Wall on the east bank of the North Tyne, and immediately opposite the East Gate at Chesters Roman Fort

Chesters was primarily a cavalry fort, and there are the remains of stable barracks on the northeast corner of the fort. Elsewhere the commanding officer’s house gives some indications still of how much better he must have lived with his family than the ordinary troops. There are remains of underfloor heating and the like that must have made living in the harsh climate of Northumberland that little bit more bearable. Just beyond the commanding officer’s house, closer to the river are the ruins of the substantial bathhouse.

Housesteads

It’s a half mile walk uphill from the car park beside the B6318 to the main entrance to the fort. The English Heritage shop and cafe are next to the car park.

What is particularly impressive about Housesteads is its remote location. There are spectacular views from the fort over the surrounding Northumberland landscape, in all directions. And the fort and Hadrian’s Wall are intimately connected. It must have been an important site along the wall, in defence of the empire.

What is particularly impressive about Housesteads is its remote location. There are spectacular views from the fort over the surrounding Northumberland landscape, in all directions. And the fort and Hadrian’s Wall are intimately connected. It must have been an important site along the wall, in defence of the empire.

Among the more intact buildings is the granary, that was used to dry or keep dry any cereals and presumably other perishables.

At the bottom of the slope, in the southeast corner stand the remains of the communal latrine, which must be one of the best preserved examples.

We didn’t visit the museum close by the fort during this visit. I had seen evidence displayed there—or was it at Vindolanda just over two miles away to the southwest?—of letters received or never sent by a soldier who hailed from Syria or somewhere in that region. Roman auxiliaries came from all over the empire, and could acquire citizenship after more than 20 years service. So, as I’ve commented elsewhere, the Romans must have left more behind than just impressive ruins. Their legacy lives on in the genetics of this part of the country.

On a bright and sunny day when we visited in June, Housesteads is a great destination for all the family. From what we experienced that day, children were having a great time exploring the fort—especially the latrine! Given its exposed location, a less clement day would make for a challenging visit.

In case you would like to see more of the photos I took during this visit (and more details of each site), please click on the links below to open photo albums:

I’ve so much enjoyed this as my ancestors can be traced directly back to Kent County in England. This part of history fascinates me!

LikeLiked by 1 person