Perhaps the most memorable six words that Charles Dickens (1812-1870) ever wrote. They appear very early on in his second novel, Oliver Twist, published in 1837. Young Oliver, ‘desperate with hunger, and reckless with misery‘ is emboldened to ask for another bowl of weak porridge (gruel). Much to the consternation of the master of the workhouse where Oliver had been sent.

L: Dickens in 1837 (from Charles Dickens in 1837 (from: http://www.photohistory-sussex.co.uk/DickensCharlesPortraits.htm; and R: a photograph taken during the last two years of his life between 1868 and 1870.

Oliver Twist was the first of Dickens’s social novels in which he wrote about the inequalities and hypocrisies of Victorian England, particularly London. I’ve never read Oliver Twist nor most of Dickens’s novels. Just a couple that were on the English curriculum at school. Or I’ve viewed them as film or TV adaptations (at which the BBC generally excels).

Things changed in January, after I’d read a book about ‘the real Oliver Twist‘. I decided to set myself a literary challenge: to read all 15 of Dickens’s novels during 2017. Or should that be 14¾, as one novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood was unfinished at the time of Dickens’s death in 1870? And so I began to work my way through them (on my Kindle), but not in the order that they were published. I recently came across a link on the BBC Magazine website in which journalist Matthew Davis described taking the ‘Dickens Challenge’ in 2012, the bicentenary of Dickens’s birth.

In July (after about eight novels), I took a short ‘Dickens break’ to read a couple of books I’d purchased at Half Price Books in St Paul while visiting Hannah and Michael and family in June. One was the ‘real’ story about Wyatt Earp and the Gunfight at the OK Corral in 1880s Arizona. The other was an biography and analysis of Confederate President Jefferson Davis’s role during the Civil War, by Princeton Emeritus Professor James P McPherson.

And now, in October, I’ve just finished the last one: Oliver Twist, which I deliberately left until last, even though it’s one of his early novels, because it was the ‘idea’ of Oliver Twist that set me off on this challenge in the first place. I enjoyed Dickens’s novels far more than I ever expected to from the outset. In fact, I found most to be quite a delight. My only other experience with Dickens was, as I said, at school: David Copperfield and Great Expectations. Unlike my latest experience, we didn’t read them for enjoyment, but to make a thorough analysis: the development of characters; the narrative; the social context, and the like.

These novels are not particularly easy reading – maybe reading them on a Kindle had something to do with that. But Dickens’s style is not the easiest to navigate, and often I had to read different paragraphs in each novel more than once to fully comprehend the narrative. He had a love affair with the semi-colon! And of course, he employed words (or their usage) that have now fallen out of fashion. These examples come to mind: benignant (kindly and benevolent); anent (concerning, about), and apostrophe (‘a digression in the form of an address to someone not present, or to a personified object or idea’).

Dickens wrote his novels between 1836 and 1870, most of them appearing in serial form before being published as books. He also wrote many other short stories and essays, the most popular among them (and indeed one of the most popular of all Dickens’s works) is A Christmas Carol (1843).

This is the order in which I approached them (with year of publication in parenthesis, and the length in words; as you might imagine, there’s a wealth of information about Charles Dickens on the web):

- David Copperfield (1849): 357,489

- Bleak House (1852): 355,936

- A Tale of Two Cities (1859): 137,000

- Little Dorritt (1855): 339,870

- The Old Curiosity Shop (1840): 218,538

- Hard Times (1854): 104,821

- Martin Chuzzlewit (1843): 338,077

- The Pickwick Papers (1836): 302,190

- Nicholas Nickleby (1838): 323,722

- Barnaby Rudge (1841): 255,229

- Our Mutual Friend (1864): 327,727

- Dombey and Son (1846): 357,484

- Great Expectations (1860): 186,339

- The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1870): 96,178

- Oliver Twist (1837): 158,631

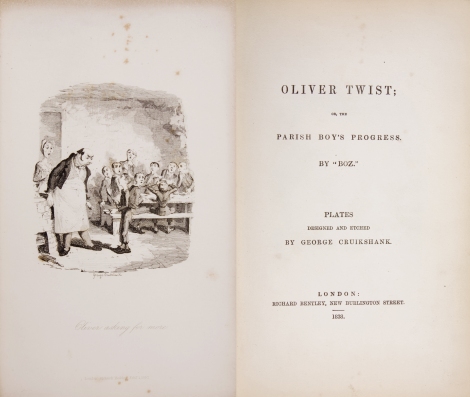

These are the covers from the original publications:

So, which novel did I enjoy the most, and which memorable characters made an impression? After almost 3,900,000 Dickensian words it’s actually quite hard to make a choice. However, a choice is what I have to make, and on reflection I have plumped for his first novel, The Pickwick Papers. While there is humour throughout most (if not all) his novels (although some are quite dire in terms of the descriptions of the society in which his characters barely survive) I did find myself laughing out loud when working my way through The Pickwick Papers. Oliver Twist is my second choice. Interesting that these two are Dickens’s first two novels.

Money—or the want of it—is a theme that runs through all Dickens’s novels. Many are set in London, or the Home Counties surrounding London. Dickens was a true wordsmith; he could capture in a few words the squalour and poverty that was the daily backdrop to the lives of most Londoners. However, Dickens does wander further afield in some novels. In David Copperfield, a good part of the narrative is set in Great Yarmouth, while the hero of Nicholas Nickleby spends time at Dotheboys Hall, a school in Yorkshire. Hard Times is set in the industrial North. In The Old Curiosity Shop, Nell and her grandfather pass through industrial Birmingham, perhaps the Black Country, ending up, I believe, in Shropshire. A Tale of Two Cities is divided between London and the Paris of Revolutionary France.

Just one novel, Bleak House, has a female narrator, Esther Summerson. David Copperfield and Great Expectations are narrated in the first person. Two are set among actual historical events: the French Revolution, in A Tale of Two Cities; and in Barnaby Rudge, the anti-Catholic Gordon Riots of 1780 are the backdrop to the narrative, and the chief protagonist of the riots, Lord George Gordon, actually appears as one of the characters in the novel. It’s also interesting to note the changes in society, the industrialization taking place (in The Old Curiosity Shop or Hard Times), or the coming of and increasing reliance on the railways (Our Mutual Friend) to move about the country.

Such a cast of characters, hundreds even, appear in Dickens’s novels: the heroes and herioines in each; the gentle ‘giants’ such as Joe Gargery in Great Expectations, or Daniel Peggoty in David Copperfield; the spongers like Harold Skimpole in Bleak House, and William Dorritt (who is also a snob and a hypocrite) in Little Dorritt; or the financially inept (but reproductively prolific) Mr Micawber in David Copperfield; hypocrites Pecksniff in Bleak House or Sir John Chester in Barnaby Rudge; and tyrants Edward Murdstone (David Copperfield’s step-father) or Ralph Nickleby in Nicholas Nickleby. There are bullies (who are really cowards, as bullies most often are) such as Mr Bumble in Oliver Twist, and the unforgettable schoolmaster Wackford Squeers in Nicholas Nickleby. And who can forget Fagin, the Jewish fence (receiver of stolen goods) in Oliver Twist, my dear?

Dickens’s characters encompass all levels of society, from the aristocracy, landowners and gentlemen of private means, and industrialists, to honest journeymen, workers and labourers, and finally the lowest level of society, the abject poor brought up in the workhouse, dependent on the parish. That last aspect, told through Oliver Twist, was the reason for me coming to Dickens this year.

So many characters, many with wonderful Dickensian made-up names*. But I must single out two of them. Although I have read Great Expectations twice before (at school), I hadn’t appreciated just what a little prig the main character Pip is, or so it seemed to me. He came across as a self-centered, obnoxious individual, something I’d not picked up on before this reading.

But I think that Dickens’s most glorious invention must be Daniel Quilp, a ‘malicious, grotesquely deformed, hunchbacked dwarf moneylender’, in The Old Curiosity Shop. If they ever decide to adapt it again for screen (large or small)—silent movie versions were made as early as 1914 and 1921—I think Danny DeVito might just fit the bill (provided he can ‘get’ the accent—we don’t want faux Cockney in the style of Dick Van Dyke in Mary Poppins).

In a recent comedy series on BBC2, of just six episodes, Quacks followed the ‘progress of four medical pioneers in the daring and wild days of Victorian medicine’. In one episode, a female character, an aficionada of Dickens’s writing, secures an invitation to dinner with the great man of letters, along with a friend. This is how the hilarious conversation about Dickens’s characters progresses during dinner.

There have been some famous Dickensian adaptations for the screen. In 1946, Great Expectations starred a young John Mills and Alec Guinness. A ‘controversial’ three-part series of Great Expectations appeared on the BBC in 2011, with Gillian Anderson (who also appeared in an earlier BBC adaptation of Bleak House) as Miss Havisham, the best interpretation I have seen.

There have been some impressive adaptations of A Christmas Carol, probably the most memorable being the 1951 adaptation Scrooge, in black and white, starring Alastair Sim. And don’t forget The Muppets (with Michael Caine as Ebenezer Scrooge). There have also been theatrical and musical versions, among the most well known being Lionel Bart’s Oliver! in 1968.

Dickensian was a wonderful 20 part series broadcast on the BBC between December 2015 and February 2016, which brought into a single story-line, set in one Victorian London neighbourhood, some of Dickens’s most iconic characters that appeared in five of his books. It was a revelation, a real mash-up, and critically well-received.

So now my 2017 Dickens challenge is at an end. In the past, I have worked my way through Jane Austen, Thomas Hardy, Anthony Trollope, some Brontë and George Elliott. Next authors? Suggestions? Decisions, decisions!

In the short-term, I’ll probably return to my other literary interest: biography and history. I already have several more biographies of American Civil War generals to work through.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

* The cast of Quacks held a quiz on Dickensian names, with hilarious results. Truly Dickens or Falsely Dickens?