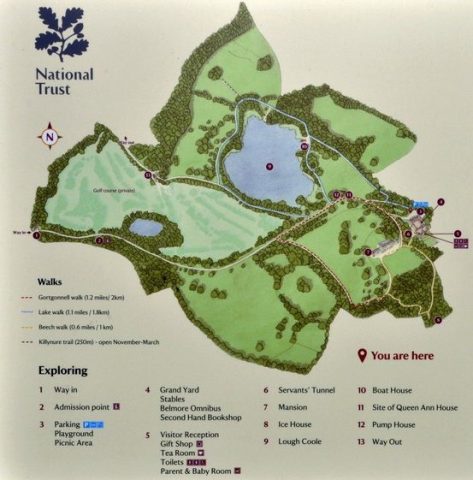

With extensive parkland, some of the most beautiful formal gardens, an elegant yet somewhat understated house that simply oozes wealth, position, and history, Mount Stewart on the Ards Peninsula in Co. Down has everything (map).

The Mount Stewart estate (then known as Mount Pleasant) was purchased in 1744 by wealthy merchant Alexander Stewart. His son became the 1st Marquess of Londonderry in 1816. Mount Stewart is the family home.

If I mentioned the name Robert Stewart, this would probably just evince a shrug of the shoulders. Mention Viscount Castlereagh, however, and the reaction would probably be very different, as he was one of the most influential politicians and diplomats of his age, Foreign Secretary in the British government, and a visionary of the Congress of Vienna in 1814-15 that sought to re-establish peace and order (and national borders) to post-Napoleonic Europe. Castlereagh became the 2nd Marquess of Londonderry in 1821 on the death of his father, the 1st Marquess. Yet he had committed suicide just a year later, and the title passed to his half-brother, Charles, who married (as his second wife) one of the wealthiest heiresses of the age, Lady Frances Anne Vane-Tempest. Her wealth gave the impetus for expansion and refurbishment of Mount Stewart. Charles had served as one of the Duke of Wellington’s generals in the Peninsula War, and was Ambassador to Austria at the time of the Congress of Vienna. After this marriage, the family name became, and continues as, Vane-Tempest-Stewart.

Mount Stewart became the principal home of the 7th Marquess and his wife Edith. She was a great socialite and political hostess, and much of today’s decor and the impressive formal gardens are due to her influence and creativity. Their youngest daughter, Mairi, their only child to be born there, was bequeathed Mount Stewart in the 7th Marquess’s will. One of Mairi’s daughters, Lady Rose Lauritzen, still has an apartment at Mount Stewart, and while we were touring the house, I saw her describing some ‘Congress chairs’ to one of the National Trust volunteers in the dining room.

There’s so much to see at Mount Stewart. It must be the ‘Jewel in the Crown’ of the National Trust in Northern Ireland. I’ve read that the Mount Stewart is counted among the world’s top ten gardens!

So let’s start with the grounds, followed by the formal garden, and then a tour of the house.

We took the lakeside walk, about a mile and a half, encountering the White Stag of Celtic legend, and visiting the family burial plot, Tir n’an Og.

To the south of the house, and up a slight hill about 10 minutes walk, you can find the Temple of the Winds, built in the late 18th century (before the house was even built). There are wonderful views over Strangford Lough to the west, and Scrabo Tower, just south of Newtownards on the other side of the lough. Scrabo Tower was constructed in 1857 as a memorial to Charles, 3rd Marquess. It has now been re-opened in partnership with the National Trust.

On the west side of the house, which faces southwest, there is a Sunken Garden and the Shamrock Garden, with a topiary Irish harp, as well as the Red Hand of Ulster planted with bright red salvias. Along the top of the hedges, there are other topiary figures.

You enter the larger garden through an impressive black and gilded gate. What a feast for the eyes, with lots of mythical animals, extinct ones like the dodo for example, and one clearly male fox!

You can explore the house on your own, but there are very knowledgeable and friendly National Trust volunteers in each room, ready and able to fill in the detail.

The entrance hall is quite unexpected, as you first pass through a modest vestibule, with the hall opening out into a sea of light.

Passing from the hall, towards the dining room, there is a very large portrait of the 3rd Marquess above an arch. To one side are some cabinets with articles of the family’s wealth and connections on display. In the room itself, there is a fine portrait of Castlereagh (the 2nd Marquess), and the ‘Congress chairs’ lining the wall beneath a portrait of a familiar figure: Napoleon Bonaparte.

From the dining room, you can enter the study of the 7th Marquess, and through to a Saloon-cum-breakfast room. The ceiling rose is mirrored in the beautiful inlaid woodwork on the floor. The table standing in the middle of the room is a so-called Irish coffin or wake table.

Lady Edith developed her own drawing room, luxuriously furnished, but homely at the same time. There’s a portrait of her on the wall.

At the bottom of the staircase, there are cabinets on either side displaying the family china. The cantilevered staircase divides halfway up, beneath a huge painting of a racehorse, that’s clearly out of proportion: in the horse itself, the length of the groom’s legs, and the right arm of the other boy.

Finally, in a large and very grand drawing room the walls are covered with portraits of family members, and lined with other objets d’art.

It’s no wonder that Mount Stewart is one of the National Trust’s most popular destinations. The history of the house and the family is almost unparalleled. And if you are ever in Northern Ireland, the trip out to Strangford Lough and Mount Stewart has to be high on your list of attractions. We were not disappointed. You won’t be either.

Florence Court sits well in its landscape, the estate nestling below

Florence Court sits well in its landscape, the estate nestling below

There is privately-owned castle (not open to the public) on the Crom Estate, home to the Creighton (or Chrichton) family,

There is privately-owned castle (not open to the public) on the Crom Estate, home to the Creighton (or Chrichton) family,