Over the centuries, the coast of northeast England has been notoriously dangerous for shipping. Many will know of the tale of Grace Darling, daughter of the lighthouse keeper on the Farne Islands who, with her father, rescued nine members of the crew of the SS Forfarshire that went aground in September 1838.

Grace Darling rescuing sailors from the SS Forfarshire, painted by Thomas Musgrave Joy in 1840

There are several hundred shipwrecks lying on the seabed off County Durham and Northumberland, many from the nineteenth century when this stretch of coastline was one of the busiest in the world. Millions of tons of coal were carried from the northeast coalfields on dangerously overloaded colliers and foundering in the rough seas that often batter this coast.

To protect mariners sailing these waters a chain of lighthouses was constructed over the centuries, with a number being erected in the 1800s. Several have already been decommissioned.

Looking for a destination for a day trip earlier this week, I suggested to Steph that we should head south of the River Tyne and take a look at Souter Lighthouse that has been standing on the cliffs overlooking the North Sea at Whitburn (map) for a century and a half, and protecting shipping against the dangerous reefs of Whitburn Steel in the immediate vicinity.

Yes, there’s been a lighthouse here since 1871. And it has a particular claim to fame. It was the first lighthouse powered by electricity in the country. Until earlier this year Souter was believed to be the world’s first lighthouse powered by electricity, but further research has apparently revealed that’s not the case (although I haven’t yet discovered which one now claims that accolade). However, it may be the world’s first purpose-built lighthouse powered by alternating electric current. The lighthouse was not automated, but in the late 1970s an electric motor replaced the clockwork mechanism that turned the lamp. The lighthouse needed four keepers and an engineer to keep the lamp lit.

The lighthouse was decommissioned in 1988, although it continued as a radio navigation beacon until 1999. It’s now owned and maintained by the National Trust, as is the surrounding land which has its own remarkable story to tell.

As a destination, Souter Lighthouse couldn’t have been more convenient, being just 11 miles and less than half an hour from home, down the A19 and crossing the River Tyne through the Tyne Tunnel. The mouth of the River Tyne is less than three miles to the north of the lighthouse.

Souter Lighthouse, a brick tower, stands at 77 feet or 23 meters. There are 76 steps up to the lantern platform. Its characteristic external marking is a single broad red band.

From the lantern platform the horizon on the clear day we visited was about 14 nautical miles.

The red lamp, which flashes for one second, every five seconds, has a range of about 26 nautical miles. It weighs 4½ tons, and ‘floats’ on a bed of 1½ tons of mercury. The mechanism is so friction free, that it can be rotated with just the slightest assistance, as Steph demonstrated.

The National Trust provides a detailed description of the lamp on its website.

The original 800,000 candle lamp was generated using a carbon arc lamp, later replaced by more conventional bulbs.

On a landing just below the lamp, there is another innovation. Landward or ‘wasted’ light was used to direct ships away from dangerous rocks near Sunderland Harbour.

The central green column in the tower housed the weights that descended due to gravity, causing a clockwork mechanism to turn the lamp above, in much the same way that a grandfather clock works. And this mechanism was wound every hour. The weights were never allowed to descend the whole height of the tower.

A steam engine generated the electricity; mains electricity didn’t arrive until 1952. The engine house is now the National Trust cafe. Next door, original tanks stored pressurized air (at 60 psi) to power the huge foghorns closer to the cliff, which sounded every two minutes when needed.

There are six cottages in a single block at Souter (two now converted to holiday cottages). Souter was regarded as a desirable posting because, being land-based, it meant that keepers could live with their families. But the two up – two down cottages must have been very cramped for families with up to nine children. And with no mains electricity, gas, or water, on stormy days when the children could not play outside, living conditions for beleaguered housewives must have been stressful indeed. Notwithstanding that lighthouse keepers at Souter earned an annual wage of around £400 (=£45,000 or so today), about ten times that of a laborer.

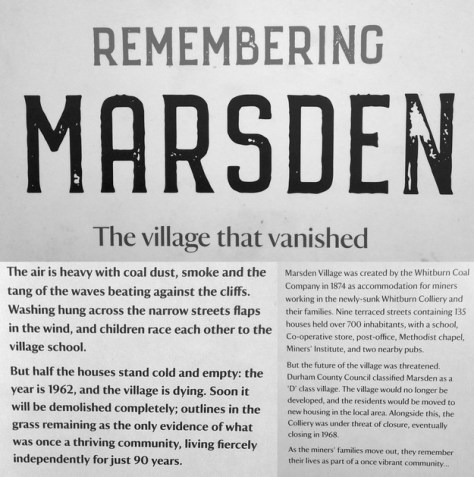

Souter Lighthouse stood alone in the landscape for just a handful of years. In 1874, a coal mine was opened just to the south of the lighthouse, and Marsden mining village, with 135 terraced houses in nine streets for more than 700 inhabitants was developed to the north of the lighthouse. Across the road there is a huge magnesian limestone quarry and the ruins of lime kilns that were fired using coal from the adjacent colliery. Over 2000 tons of coal were brought to the surface each day. The coal galleries stretched for several miles out under the North Sea. In 1968 the mine was closed and eventually the village abandoned, before being demolished.

Looking at this photo below, taken from the top of the lighthouse, it’s hard to imagine that there was once a thriving community in that open space.

Looking north from the top of Souter Lighthouse, over the site of the ‘lost village’.

The Marsden lime kilns

Here’s a short video of more Marsden history.

What Steph and I hadn’t appreciated before we headed to Souter Lighthouse is the beauty of this stretch of coast, with limestone cliffs, populated by numerous seabirds, standing maybe 50 feet or so above the crashing waves.

Cormorants and kittiwakes

Even though the sea was calm, we were surprised at the size of some waves that hit the rocks.

Anyway, we took a walk about 2 miles south of the lighthouse, and enjoyed the many views of coves, rock stacks, and south as far as the North York Moors near Whitby, maybe 30 miles away. This map shows only half the distance we walked, eventually reaching the southern end of Whitburn beach.

This visit to Souter Lighthouse was one of the most enjoyable National Trust visits that we’ve had in a long time. Well, the Covid pandemic hasn’t helped with our visits. But it wasn’t just the beautiful sunny weather, the awesome cliff landscapes, and the interesting history of the lighthouse itself (I learned a lot about the network of lighthouses around our coasts that I hadn’t appreciated before). The National Trust volunteers who showed us around the lighthouse were friendly, knowledgeable and more than willing to share insights about the property.

I’m sure we’ll be making another visit before too long. In case you’d like to see more photos of our visit, you can open an album of photos and videos here.

Hi Mike,

thank you for all the information and your pictures. The next time we’ll be in your area we’ll surely visit this lighthouse. We love lighthouses. Was this lighthouse build by one of the Stevensons?

Thanks and cheers

The Fab Four of Cley

🙂 🙂 🙂 🙂

LikeLike

I’m glad you enjoyed reading the post. It was designed by James Douglass in 1871.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you.

LikeLike