In October 1967 (when I started my undergraduate studies in [Environmental] Botany and Geography¹), The University of Southampton was a very different institution from what it is today. So many changes over the past 50 years! One of the biggest changes is its size. In 1967 there were around 4500-5000 undergraduates (maybe 5000 undergraduates and postgraduates combined) if my memory serves me well, just on a single campus at Highfield.

In October 1967 (when I started my undergraduate studies in [Environmental] Botany and Geography¹), The University of Southampton was a very different institution from what it is today. So many changes over the past 50 years! One of the biggest changes is its size. In 1967 there were around 4500-5000 undergraduates (maybe 5000 undergraduates and postgraduates combined) if my memory serves me well, just on a single campus at Highfield.

Today, Southampton is a thriving university with a total enrolment (in 2015/16) of almost 25,000 (70% undergraduates) spread over seven campuses. Southampton has a healthy research profile, a respectable international standing, and is a founding member of the Russell Group of leading universities in the UK.

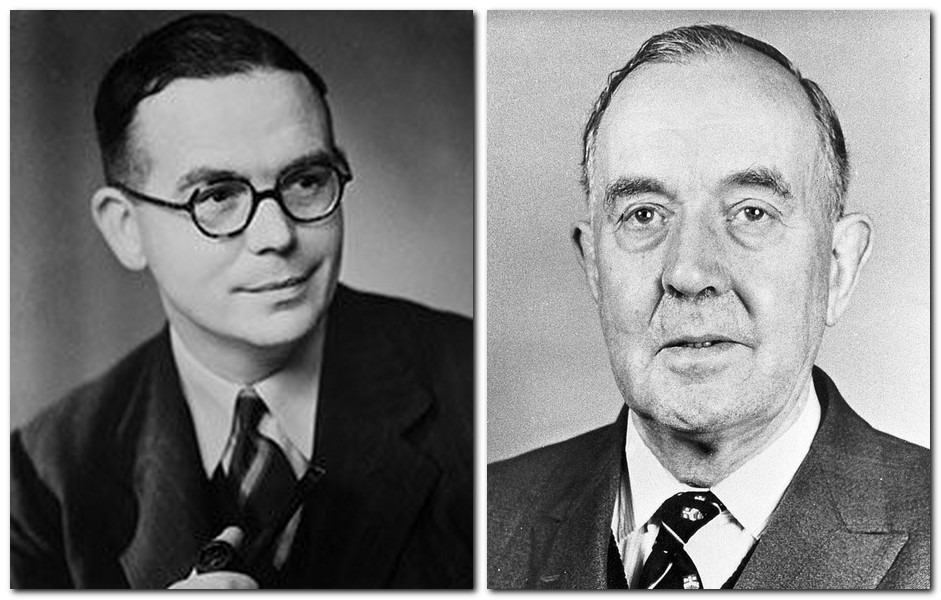

In 1967, the university was led by Vice-Chancellor Professor Sir Kenneth Mather² FRS (1965-1971), an eminent biometrical geneticist, who came to Southampton from the Department of Genetics at The University of Birmingham, where he had been head of department. The Chancellor (1964-1974) was Baron Murray of Newhaven.

(L) Professor Sir Kenneth Mather and (R) Lord Keith Murray (from Wikipedia)

The campus

Looking at a map of the Highfield campus today, many new buildings have risen since 1967, departments have moved between buildings, and some have relocated to new campuses.

In the 1960s, Southampton had benefited from a period of university expansion and new infrastructure under the then Conservative Government (how times have changed), with Sir Edward Boyle at the helm in the Department for Education or whatever it was named in those days.

Until about 1966 or early 1967, Botany had been housed in a small building immediately north of the Library, which has since disappeared. It was one of the early beneficiaries of the ‘Boyle building expansion’ at Southampton, moving to Building #44, shared with Geology.

After I left Southampton in the summer of 1970, Botany and Zoology merged (maybe also with physiology and biochemistry) to form a new department of Biological Sciences at the Boldrewood Campus along Burgess Road, a short distance west of the Highfield Campus. Biological Sciences relocated to a new Institute for Life Sciences (#85) on the main campus at Highfield a few years back.

Geology now resides within Ocean and Earth Science, National Oceanography Centre Southampton located at the Waterfront campus on Southampton Docks.

The Geography department had been located on the first floor of the Hartley Building (#36, now entirely devoted to the university library). By autumn 1968, Geography moved to a new home in the Arts II Building (#2). For some years now it has occupied the Shackleton Building (#44), the former Botany and Geology home.

Spending more time in Botany

As Combined Honours students, the four of us had feet in two departments, and tutors in each. We took the full Single Honours botany course for the first two years, but in the final year, specialised in plant ecology, with a few optional courses (such as plant speciation, plant breeding, and population genetics in my case) taken from the botany common course that all Single Honours students took. I also sat in our the plant taxonomy lectures given by Reading professor and head of the department of botany there, Vernon Heywood, who traveled to Southampton twice a week for five or six weeks. In the early 1990s I crossed paths with him in Rome where we were attending a conference at FAO, and enjoyed an excellent meal together and an evening of reminiscing.

Students complain today that they have few formal contact hours during their degree courses. Not so at Southampton in the late 1960s. But that was also a consequence of taking two subjects with a heavy practical class load, and an ancillary, Geology, for one year, also with a practical class component.

During the first term, Fridays were devoted to practical classes from 9-5 with a break for lunch. In the mornings we spent 10 weeks learning about (or honing existing knowledge) plant anatomy, taught by cytologist Senior Lecturer Dr Roy Lane. Afternoons were devoted to plant morphology, taught by Reader and plant ecologist Dr Joyce Lambert. In the Spring Term in 1968, we started a series of practical classes looking at the flowering plants. Ferns and mosses were studied in the second year.

In the second year, we focused on genetics, plant biochemistry, plant physiology, and mycology, taught by Drs. Joe Smartt, Alan Myers, David Morris, and John Manners. On reflection, the genetics course was pretty basic; most of us had not studied any genetics at school. So practical classes focused on Drosophila fruit fly crossing experiments, and analysing the progeny. Today, students are deeply involved with molecular biology and genomics; they probably learn all about Mendelian genetics at school. During the second year, plant taxonomist Leslie Watson departed for Australia, and this was the reason why Vernon Heywood was asked to cover this discipline later on.

The structure of the Single Honours Botany course changed by my final year. There was a common course covering a wide range of topics, with specialisms taken around the various topics. For us Combined Honours students, we took the plant ecology specialism, and three components from the common course. We also had to complete a dissertation, the work for which was undertaken during the long vacation between the second and third years, and submitted, without fail, on the first day of the Spring Term in January. We could choose a topic in either Botany or Geography. I made a study of moorland vegetation near my home in North Staffordshire, using different sampling methods depending on the height of vegetation.

We made two field courses. The first, in July 1968, focusing on an appreciation of the plant kingdom, took us to the Burren on the west coast of Ireland in Co. Clare. We had a great time.

The last morning, Saturday 27 July 1968, outside the Savoy Hotel in Lisdoonvarna. In the right photo, L-R, back row: Alan Myers, Leslie Watson (staff), Jenny?, Chris ? (on shoulders), Paul Freestone, Gloria Davies, John Grainger, Peter Winfield. Middle row: Janet Beazley and Nick Lawrence (crouching) Alan Mackie, Margaret Barran, Diana Caryl, John Jackson, Stuart Christophers. Sitting: Jill Andison, Patricia Banner, Mary Goddard, Jane Elliman, Chris Kirby (crouching)

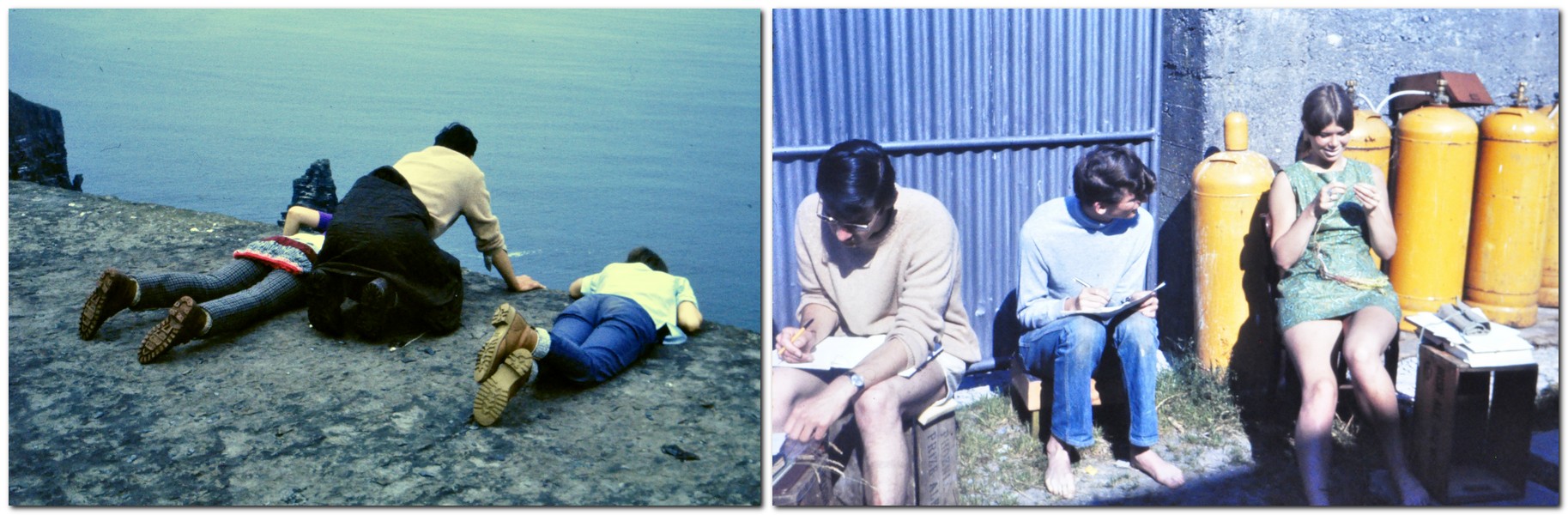

Checking out the Cliffs of Moher, and working on individual projects (Paul Freestone, John Grainger, Jane Elliman)

We all had to carry out a short project, in pairs, and I worked with Chris Kirby on the brown algae abundant on the coast near Lisdoonvarna which was our base. At the end of the second year, we spent two weeks in Norfolk, when the Americans first landed on the Moon. Led by Joyce Lambert and John Manners, the course had a strong ecology focus, taking us around the Norfolk Broads, the salt marshes, the Breckland, and fens. We also had small individual projects to carry out. I think mine looked at the distribution of a particular grass species across Wheatfen, home of Norfolk naturalist (and good friend of Joyce Lambert), Ted Ellis.

Professor Stephen H Crowdy was the head of department. He had come to Southampton around 1966 from the ICI Laboratories at Jealott’s Hill. He was an expert on the uptake and translocation of various pesticides and antibiotics in plants. I never heard him lecture, and hardly ever came into contact with him. He was somewhat of a non-entity as far as us students were concerned.

Joyce Lambert in 1964

Joyce Lambert was my tutor in botany, a short and somewhat rotund person, a chain-smoker, known affectionately by everyone as ‘Bloss’ (short for Blossom). Her reputation as a plant ecologist was founded on pioneer research, a stratigraphical analysis of the Norfolk Broads confirming their man-made origin, the result of medieval peat diggings. Later on, with her colleague and head of department until 1965, Professor Bill Williams, Joyce developed multivariate methods to study plant communities. This latter research area was the focus of much of her final year teaching in plant ecology. Joyce passed away in 2005.

Joe Smartt

I became a close friend of Joe Smartt, who retired in 1996 as Reader in Biology, and a highly respected expert on grain legumes. It was Joe who encouraged my interest in the nexus between genetics and ecology, which eventually led to me applying to Birmingham in February 1970 to join the MSc course on Conservation and Utilization of Plant Genetic Resources – in September that year, the beginnings of my career in genetic resources conservation. Outside academics, Joe and I founded a Morris dancing team at Southampton, The Red Stags, in October 1968, and its ‘descendant’ is still thriving today. Joe passed away in June 2013.

A young Alan Myers in 1964

I also had little contact outside lectures and practical classes with the other staff, such as physiologists Alan Myers and David Morris, or cytologist Roy Lane. In the late 1980s, when I was a lecturer in plant biology at The University of Birmingham, as internal examiner I joined plant pathologist John Manners (the external examiner) to examine a plant pathology PhD dissertation at Birmingham. I hadn’t seen him since I left Southampton in 1970.

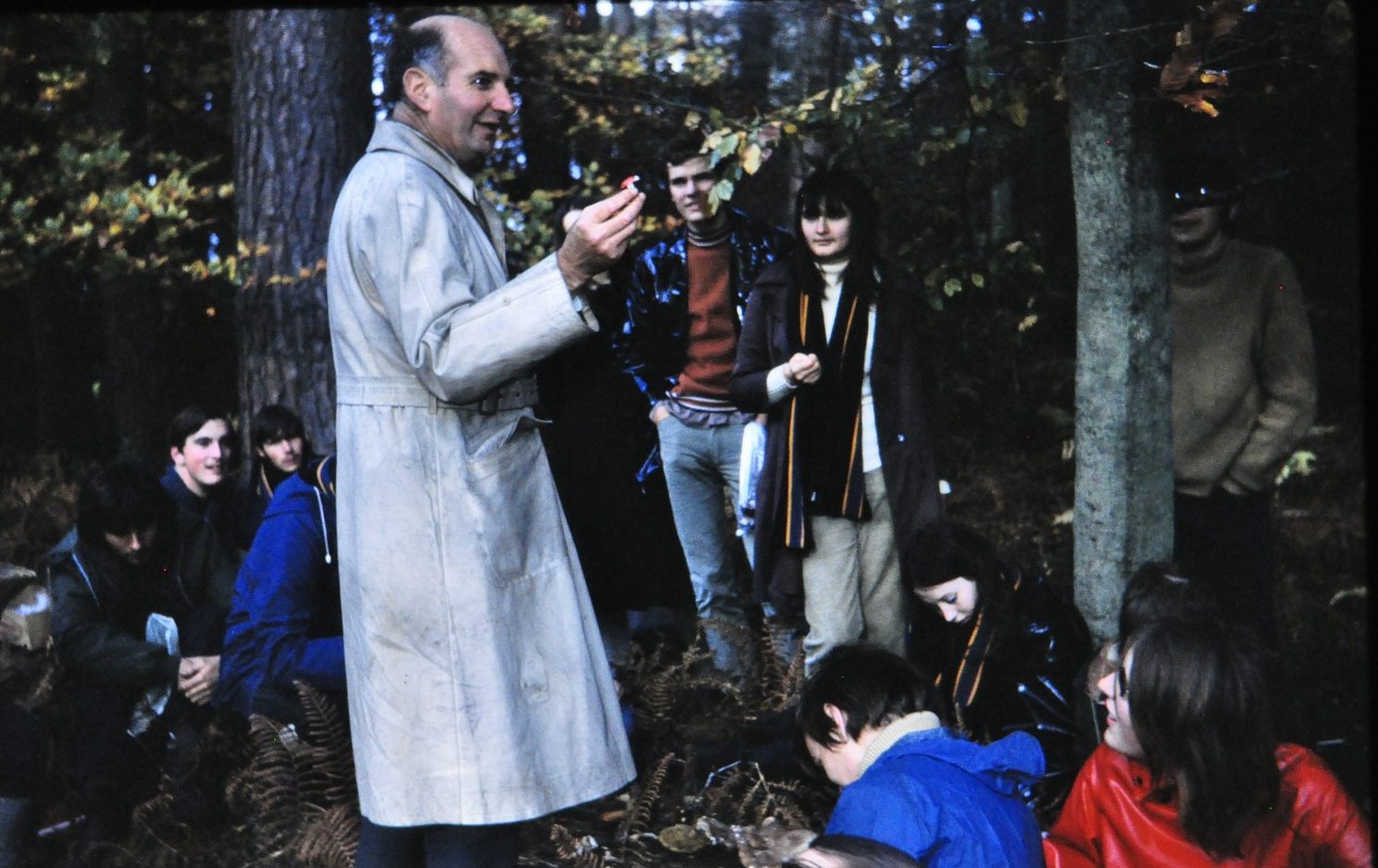

Every October he used to organize a fungus foray into the New Forest for a day. I’ve read a couple of accounts from former botany students, before my time, and how enjoyable these outings were. John was elected President of the British Mycological Society in 1968, and was a recipient of the very special President’s Medal of the Society.

October 1969 – John Manners leading a fungus foray, near Denny Wood in the New Forest

Les Watson in 1964

Leslie Watson (who came from my home town of Leek in Staffordshire) taught flowering plant taxonomy, and had an interest in the application of numerical techniques to classify plants. At some point in my second year, he joined the Australian National University in Canberra, completing several important studies on the grass genera of the world. After I had posted something a few years back on my blog, Leslie left a comment. I’ve subsequently found that he retired to Western Australia. I’ve recently been in touch with him again, and he gave me some interesting insights regarding the setting up of the combined degree course in botany and geography.

In October 1968 (the beginning of my second year), John Rodwell joined Joyce Lambert’s research group to start a PhD study of limestone vegetation. He had graduated with First Class Honours from the University of Leeds that summer. In the summer of 1969, John stayed with me in Leek for a few days while making some preliminary forays (with me acting as chauffeur) to the Derbyshire Dales. After completing his PhD, John was ordained an Anglican priest, and was based at the University of Lancaster and becoming the co-ordinator of research leading to the development of the British National Vegetation Classification. He joined the faculty at Lancaster in 1991, and became Professor of Ecology in 1997, retiring in 2004.

Until 1970 there were no re-sit exams at Southampton – unlike the general situation today nationwide in our universities. You either passed your exams first time or were required to withdraw. We lost about half the botany class in 1968, including one of the five Combined Botany and Geography students. Students could even be asked to withdraw at the end of their second year. However, after much uproar among the student body in 1969, the university did eventually permit re-sit exams.

James H Bird, Professor of Geography and head of department, 1967-1989

Geography in the late sixties

The Head of Geography was Professor James Bird, an expert on transport geography (focusing on ports) who joined the department in 1967, replacing renowned physical geographer, FJ Monkhouse. I can’t recall having seen, let alone met him more than a handful of occasions during my three years at Southampton. But from his obituary that I came across recently, he was remembered with affection apparently. He passed away in 1997.

In the Geography department I had contact with just a few staff who taught aspects of physical geography. Dr Ronald John Small lectured on the geomorphology of the Wessex region, and various tropical erosion processes. He was an excellent lecturer. After I left Southampton he authored a student text on geomorphology, published in 1970, with a second edition in 1978. He became first Reader in Geography, then Professor, and head of department (1983-1989). He retired in 1989.

His younger colleague, Michael Clark (later Professor of Geography) also taught several courses in physical geography, focusing on river erosion and weathering processes. He was only 27 in 1967, and had completed his PhD in the department just a couple of years earlier. His work evolved to focus on environmental management, water resources, coastal zone management and cold regions research and on the interactions between society and risk. His involvement in multi-disciplinary applied research and the application of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to decision-making led to the co-founding of the GeoData Institute in 1984, where he served as Director for 18 years (1988-2010). A Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, he received the Gill Memorial Award in 1983. He passed away in 2014.

His younger colleague, Michael Clark (later Professor of Geography) also taught several courses in physical geography, focusing on river erosion and weathering processes. He was only 27 in 1967, and had completed his PhD in the department just a couple of years earlier. His work evolved to focus on environmental management, water resources, coastal zone management and cold regions research and on the interactions between society and risk. His involvement in multi-disciplinary applied research and the application of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to decision-making led to the co-founding of the GeoData Institute in 1984, where he served as Director for 18 years (1988-2010). A Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, he received the Gill Memorial Award in 1983. He passed away in 2014.

The third year geomorphology class had eight students: four from Combined honours, and four single Geography honours. Among those was Geoff Hewlett/Hewitt (?), a rather intense, mature student, who was awarded one of just two Firsts in Geography. Just a week before Finals in May/June 1970, John Small took our group of eight students for a short field trip (maybe four days) to Dartmoor in Devon, to look at tropical weathered granite landscapes (the tors) there. It was also an opportunity, they divulged, to get us all away from intense revision, and to relax while learning something at the same time.

My Geography tutor during my first year was Dr Roger Barry, a climatologist who left Southampton in 1968 for a new position at the Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research at the University of Colorado, Boulder. He passed away in 2018.

Dr Brian P Birch became my tutor in my second and third years (he had interviewed me for a place at Southampton in early 1967 with Joyce Lambert from Botany). Brian taught a course on soils and their classification. But I have subsequently discovered that his interest was in settlement patterns (particularly in the US Midwest, where he had completed his Master’s degree in Indiana; he has undergraduate and PhD degrees from Durham University) and their impact on the environment. I never attended any lectures in this field from him. After contacting Prof Jane Hart at Southampton earlier in the year, she gave me Brian’s address so I wrote to him. In a lengthy reply, he told me about the evolution of the Combined Honours degree course into a fully-fledged Environmental Sciences degree, for which he was the Geography lead person. The course grew to include Geology, Oceanography, and even Chemistry. Brian took early retirement in 1990. It was lovely hearing from him after so many decades; he is now in his 80s. He recalled that on one occasion, I had turned up in the Geography department coffee room, and met with staff. He still knew all about my connections with Peru and potatoes. I wonder if that was in 1975 while I was back in the UK to complete my PhD, or later on in the 80s when I did attend a meeting in Botany/ Biological Sciences on a plant genus, Lathyrus, I was working on.

In my final year, there was a new member of staff, Keith Barber who taught Quaternary studies, and who was still completing his PhD at Lancaster University. Keith later became Professor of Environmental Change, and retired in 2009; he passed away in February 2017.

At the end of the first week of classes in October 1967, all geography students had a Saturday excursion to the northwest outskirts of Southampton (I don’t remember the exact route we took), and having been dropped off, we all walked back into the city, with various stops for the likes of Small and Clark, and another lecturer named Robinson, to wax lyrical about the landscape and its evolution and history. This was an introduction to a term long common course about the geography of the Southampton region, examined just before Christmas.

There was only one field course in Geography that I attended, just before Easter in March 1968, to Swansea (where we stayed at the university), and traveled around the region. It was fascinating seeing the effects of industrialization and mining, and pollution over centuries, in the Swansea Valley, and attempts at vegetation regeneration, as well as the physical geography of the Gower Peninsula. The weather was, like the curate’s egg, good in parts. On some days it was hot enough to wear swimsuits on the beach; other days it rained. On the morning of our departure home, there were several inches of snow!

Student life

I had a place in South Stoneham House (now demolished), an all male hall of residence about 25 minutes walk southeast from the Highfield campus. In the sixties, most of the halls of residence were single sex (some of the time – remember these were the Swinging Sixties). Across the road from Stoneham was Montefiore House, a self-catering hall mainly for mature students, and just down Wessex Lane was Connaught, another all male hall. Highfield (to the west of the campus) and Chamberlain (to the north) were all female halls; Glen Eyre (close to Chamberlain) was, if I remember, both male and female, and self catering.

Rules about occupancy were supposedly strictly enforced. Being caught was cause for expulsion from hall. However, the number of males in female halls and vice versa overnight on Fridays and Saturdays was probably quite significant.

I enjoyed my two years in Stoneham, being elected Vice-President of the Junior Common Room (JRC) in my second year. Law student Geoff Pickerill was the President of the JCR. One of my roles was to organize the annual social events: a fireworks party and dance in November, and the May Ball.

Several of my closest friends came from my Stoneham days, and Neil Freeman (Law) and I have remained in touch all these years. Neil and I moved into ‘digs’ together (with an English and History student, Trevor Boag, from York) in a house at 30 University Road, less than 100 m south of the university administration building that opened in 1969. Our landlord and landlady were Mr and Mrs Drissell who looked after the three of us as though we were family.

Neil had an old Ford Popular

The university had a very active Students’ Union in the late sixties. A new complex of cafeterias, ballrooms, meeting rooms, and sports facilities had just been completed in 1967. My main interest was folk music and dancing. I joined the Folk Club that met every Sunday evening, and even got up to sing on several occasions. I joined the English and Scottish Folk Dance Society³, and as I mentioned earlier, co-founded The Red Stags Morris in Autumn 1968. Through these dancing activities, I attended three Inter-Varsity Folk Dance Festivals in Hull (1968), Strathclyde (1969), and Reading (1970), performing a demonstration dance at each: Scottish at Hull and Strathclyde, and Morris (Beaux of London City) at Reading.

I also was involved in the University Rag Week as part of the Stoneham contributions.

In my final year, I bumped into a couple of young women in the foyer of the university library. They were from a local teaching college, and were taking part in the city-wide Rag activities. They asked me to buy a raffle ticket – which I did. Then, I suddenly asked one of the girls, who had very long hair, if her name was Jackson. You can imagine her surprise when she confirmed it was. ‘Then’, I said, ‘you are my cousin Caroline’ (the daughter of my father’s younger brother Edgar). I hadn’t seen Caroline for more than a decade, but when I was speaking with her I just knew we were related!

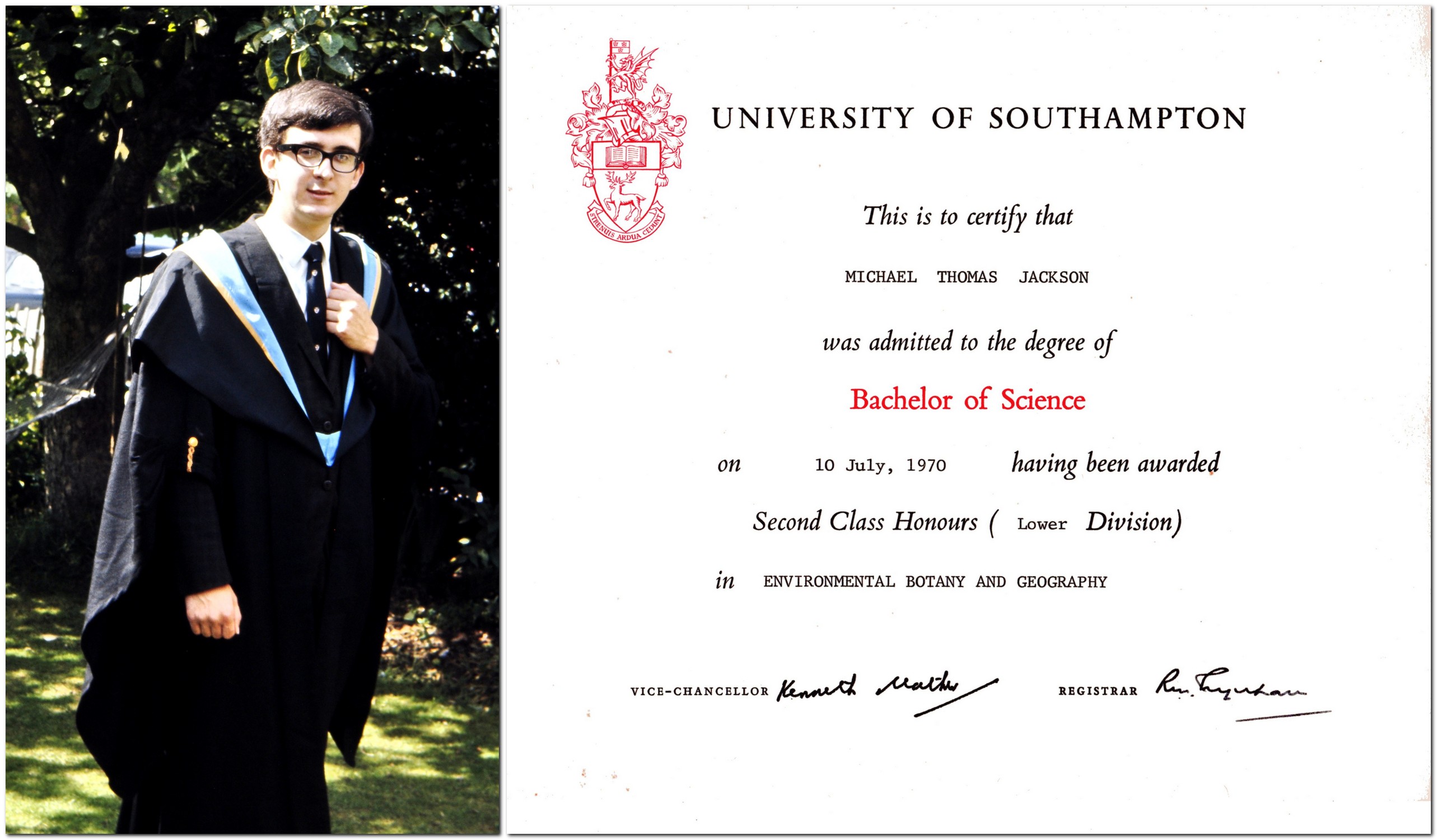

Three years passed so quickly. I graduated on 10 July 1970.

Later in September I began graduate studies at The University of Birmingham, and a career in international agricultural research for development. But that’s another story.

I spent some of my happiest years at Southampton, enjoyed the academics and the social life. I grew up, and was able to face the world with confidence. Southampton: an excellent choice.

These are some of my memories. Thinking back over 50 years I may have got some details wrong, but I think the narrative is mostly correct. If anyone reading this would like to update any details, or add information, please do get in touch. Just leave a comment.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

¹ In 1967 I applied to study Botany and Geography. During the Autumn Term of my final year, in 1969, the university changed the degree title to Environmental Botany and Geography that perhaps better reflected the course structure of (mainly) ecology on the one hand and physical geography (geomorphology, climatology, biogeography) on the other. This was probably one of the first environmental degrees.

² After he retired, Mather returned to his home in Birmingham, and became an Honorary Professor in the Department of Genetics in the School of Biological Sciences. In 1981 I joined the staff of the Department of Plant Biology (where I’d taken my PhD) in the same School. By about 1988, the four departments of the School (Plant Biology, Zoology & Comparative Physiology, Microbiology, and Genetics) had merged to form a unitary School of Biological Sciences, and I became a member of the Plant Genetics Research Group. I also moved my office and laboratory to the south ground floor of the School building, that was previously the home of Genetics. Prof. Mather had an office just down the corridor from mine, and we would meet for afternoon tea, and often chat about Southampton days. At Southampton he taught a population genetics course to a combined group of Botany and Zoology students. It was an optional course for me that I enjoyed. One day, he was lecturing about the Hardy-Weinburg Equilibrium, or some such, and filling the blackboard with algebra. Turning around to emphasise one point, he saw a young woman (from Zoology) seated immediately in front of me. She was about to light a cigarette! Without batting an eyelid, and not missing an algebraic beat, all he said was ‘We don’t smoke in lectures’, and turned back to complete the formula he was deriving. Needless to say the red-faced young lady put her cigarette away.

The late 60s were a period of student turmoil, and Southampton was not immune. Along University Road (which bisects the Highfield Campus), close to the Library, a new Administration building, with the Vice-Chancellor’s office (#37) was completed in late 1969 or early 1970 and, as rumored ahead of the event, was immediately the focus of a student sit-in, and regrettably some significant damage. However, one of Mather’s enduring legacies, however, was the establishment of a Medical School at Southampton.

³ At the first meeting of the EDFDS that I attended (probably the first week proper of term), I met a young woman, Liz Holgreaves, who became my best friend during that first year at Southampton, and we dated for many months.

Almost two weeks ago, I received the sad news from Liz’s husband, John Harvey, that she had passed away on 30 August. She was 76.

Almost two weeks ago, I received the sad news from Liz’s husband, John Harvey, that she had passed away on 30 August. She was 76.

Liz was studying English and History and I was studying Botany and Geography. Such disparate academic interests, yet we were brought together through our love of folk dancing.

When I met her for the first time, at the first meeting of the English and Scottish Folk Dance Society, I thought that I had never met a lovelier person. And, much to my delight (and perhaps even astonishment), she agreed to meet me later on in the week for a coffee.

As the weeks progressed, we went out together more and more, and by the middle of the Spring Term, our relationship had begun to blossom. During the summer vacation, I spent several weeks at her home in Church Fenton near York, and we went youth hostelling over the North York Moors, visiting Robin Hoods Bay where she had spent many happy childhood holidays.

Liz visited my family home in Leek in North Staffordshire and I was delighted to show her the beautiful Staffordshire Moorlands and the dales of Derbyshire where I grew up. She even joined my family at the wedding of my elder brother Ed and Christine in Brighton. On that evening Liz and I enjoyed a theatre show of The White Heather Club seeing many of the singers and dancers who regularly appeared on the BBC program of that same name, such as folk legends Robin Hall and Jimmy Macgregor.

Sadly, our relationship did not endure, although Liz and I remained good friends and always enjoyed dancing together. She was one of the most graceful dancers I have ever partnered.

I lost touch with Liz after I left Southampton. She and John were married in 1971. And I met Steph in 1972 at the University of Birmingham where we were graduate students.

However, moving on almost 30 years (I was working in the Philippines at the time) I came across the name of someone online who I thought might be related to Liz, and so I wrote to them. You can imagine my surprise when a long letter from Liz landed on my desk a couple of months later. Catching up on so many intervening years, we agreed to meet whenever I was next in the UK on home leave, sharing so many memories and finding out about each other’s families. She had three children: Jamie, Joseph, and Sarah. Steph and I have two daughters, Hannah and Philippa, who are much the same age as Liz’s.

Early in the 2000s, Liz wrote me that the pain she was suffering had been finally diagnosed as secondary progressive multiple sclerosis, and it was this condition (and others) that led to her going into care around 5 years ago. And despite her deteriorating health, she remained happy and always confident in the deep and enduring love of John and children.

Liz died peacefully with John holding her hand, while he and Joe read to her from one of her favourite books, as they listened to the second movement of Mozart’s 21st piano concerto, another of Liz’s favourites.

I was privileged to attend her funeral online on 14 October. It was moving ceremony, full of love and admiration for a beautiful and gentle woman. Many tears were shed.

And although I met Liz only once since we left Southampton in 1970, her passing has raised so many good memories of those times. And for that I will be forever grateful, and she continues to have a place in my heart.

My deep and sincere condolences to John, Jamie, Joe, and Sarah, and their families. Liz will be sorely missed.

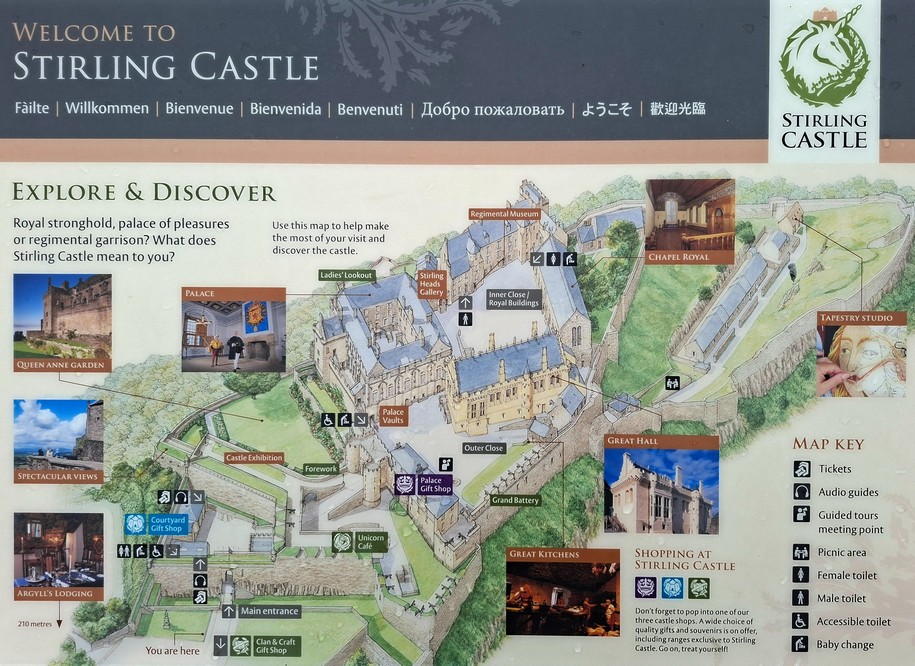

The castle reached its zenith, as a renaissance royal palace, in the 1500s and was the home of

The castle reached its zenith, as a renaissance royal palace, in the 1500s and was the home of  There’s certainly plenty to see at Stirling Castle, and by the time we ‘retired’ to have lunch, I was quite overwhelmed by all the information that I had tried to absorb.

There’s certainly plenty to see at Stirling Castle, and by the time we ‘retired’ to have lunch, I was quite overwhelmed by all the information that I had tried to absorb.

River Glen. There is a small museum dedicated to Gefrin at the distillery which we also had opportunity to view.

River Glen. There is a small museum dedicated to Gefrin at the distillery which we also had opportunity to view.

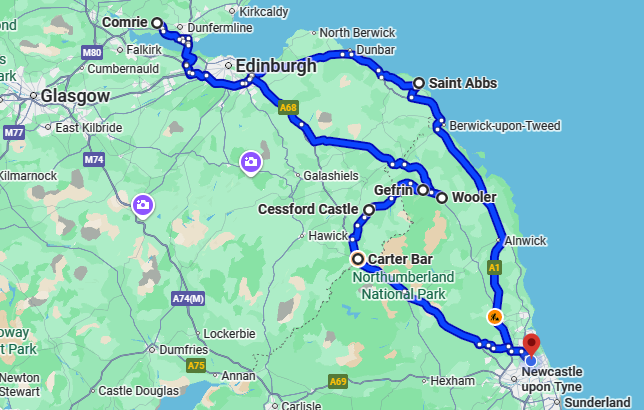

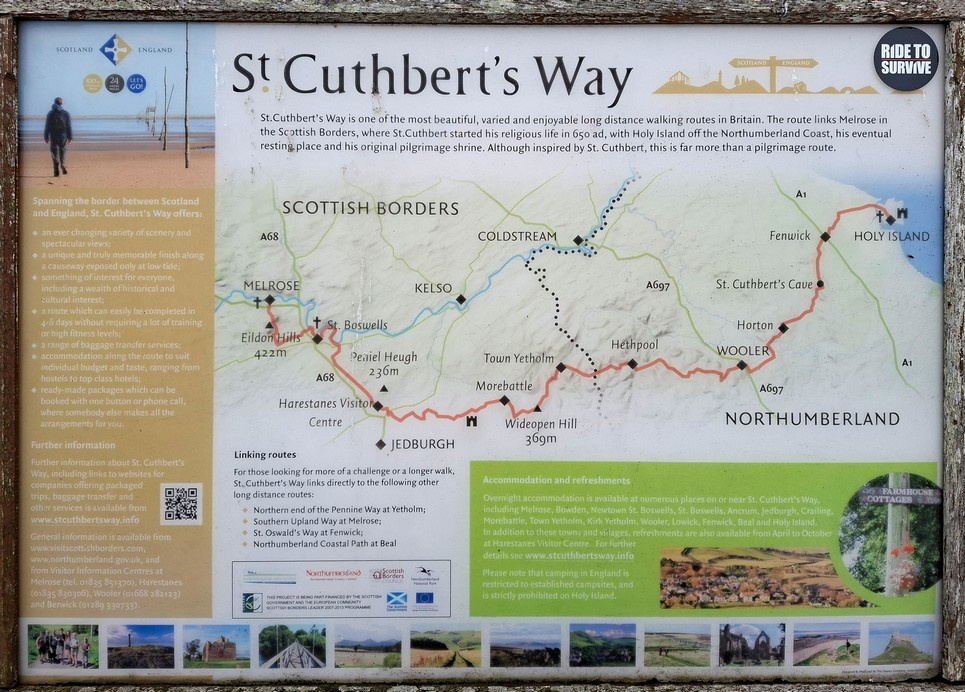

We continued our journey west, crossing over the border back into Scotland near Morebattle before arriving at

We continued our journey west, crossing over the border back into Scotland near Morebattle before arriving at

I loitered a little longer in front of the booth of the English & Scottish Folk Dance Society, and before I had chance to ‘escape’ some of the folks there had engaged me in conversation and persuaded me to come along to their next evening.

I loitered a little longer in front of the booth of the English & Scottish Folk Dance Society, and before I had chance to ‘escape’ some of the folks there had engaged me in conversation and persuaded me to come along to their next evening.

A few days ago, I received the sad news (from Liz Holgreaves husband John Harvey) that Liz had passed away on 30 August. She was 76. This photo was taken in 2006 at her elder son’s wedding.

A few days ago, I received the sad news (from Liz Holgreaves husband John Harvey) that Liz had passed away on 30 August. She was 76. This photo was taken in 2006 at her elder son’s wedding.