Current international activities surrounding the genetic resources of plants aim to confront one paradoxical problem. This is that scientists throughout the world are rightly engaged in developing better and high yielding cultivars of crop plants to be used on increasingly larger scales. But this involves the replacement of generally variable, lower yielding, locally adapted strains grown traditionally, by the products of modern agriculture – the case of uniformity replacing diversity. It is here we find the paradox, for these self-same breeders are dependent upon the availability of a pool of diverse genetic material for success in their work. They are themselves dependent upon that which they are unwittingly destroying.

Those words, still relevant today in many respects, were not written recently, but more than 40 years ago. They are the first paragraph of Chapter 1 of Plant Genetic Resources: an introduction to their conservation and use [1]. Written with my former colleague at the University of Birmingham, Brian Ford-Lloyd, this book is a short—146 page—primer about genetic conservation, originally published in 1986 by Edward Arnold, but now part of the Cambridge University Press (CUP) stable.

Those words, still relevant today in many respects, were not written recently, but more than 40 years ago. They are the first paragraph of Chapter 1 of Plant Genetic Resources: an introduction to their conservation and use [1]. Written with my former colleague at the University of Birmingham, Brian Ford-Lloyd, this book is a short—146 page—primer about genetic conservation, originally published in 1986 by Edward Arnold, but now part of the Cambridge University Press (CUP) stable.

Brian and I began writing around 1983 or 1984 for publication in 1985. As we explained in the Preface: We [were] motivated to write this book because of our stimulating association with IBPGR [the International Board for Plant Genetic Resources] and Birmingham over the past decade or so, and the general need for a text which would serve as an introduction to the field of plant genetic resources, not only for students, but also for scientists and laymen alike, who are perhaps working in other, but related, disciplines.

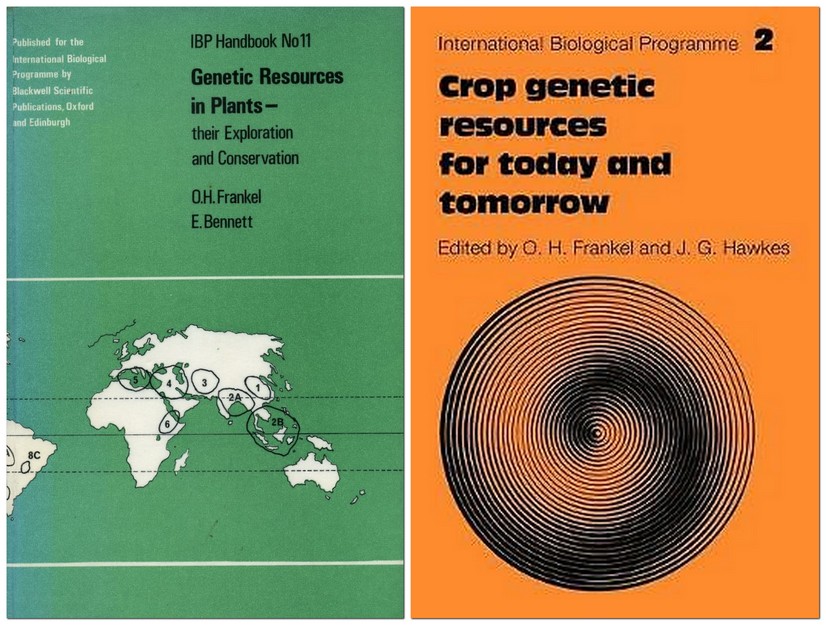

Our book was never intended to ‘rival’ a couple of standard texts [2, 3] that had launched the genetic resources conservation movement in the 1970s.

Originally, we proposed an even shorter book, part of the Edward Arnold Studies in Biology Series (published by the Institute of Biology), and intending to join such luminaries as plant breeder and John Innes horticulturist WJC Lawrence (No. 12 Plant Breeding) and renowned taxonomist Professor Vernon Heywood (No. 5 Plant Taxonomy). The Series, covering a wide range of biological topics, was aimed at teachers and students at school and university levels.

That was our intention. But after we had pitched our proposal to the commissioning editor at Edward Arnold, we were invited to write a longer version. Publication was delayed by about a year as the typesetter who sent us the first set of proofs had made such a hash of the job (literally thousands of errors), that the publisher was obliged to pull the typesetting contract and pass it on to another.

Nevertheless, Plant Genetic Resources: an introduction to their conservation and use was a best-seller. The 2500 print run (considerably more than the contracted 1000), sold out in just over a year. After the rights to the book were acquired by CUP around 2000, it was re-issued in 2010 as a digitally printed version, and still remains available on request.

But before going further, permit me to digress to provide a little more background as to how this book came about.

Brian (right) and I have been friends since September 1970 when I first arrived in Birmingham to attend the 1-year MSc course on Conservation and Utilisation of Plant Genetic Resources [4] run by the Department of Botany (later Plant Biology) in the School of Biological Sciences. I had graduated from the University of Southampton in July. Brian graduated from Birmingham at the same time and was starting a PhD project under the supervision of Dr Trevor Williams who had arrived in Birmingham a year earlier and was the MSc Course Tutor. Trevor would later move on to become the first Director General of the International Board for Plant Genetic Resources (IBPGR) in Rome [5].

Brian (right) and I have been friends since September 1970 when I first arrived in Birmingham to attend the 1-year MSc course on Conservation and Utilisation of Plant Genetic Resources [4] run by the Department of Botany (later Plant Biology) in the School of Biological Sciences. I had graduated from the University of Southampton in July. Brian graduated from Birmingham at the same time and was starting a PhD project under the supervision of Dr Trevor Williams who had arrived in Birmingham a year earlier and was the MSc Course Tutor. Trevor would later move on to become the first Director General of the International Board for Plant Genetic Resources (IBPGR) in Rome [5].

After completing his PhD on the Biosystematics of the genus Beta (beets, beetroot, and wild relatives) in 1973, Brian took a post-doctoral fellowship at Keele University in Staffordshire, before returning to Birmingham in 1976 as Lecturer in Plant Biology. He was also appointed MSc Course Tutor, Trevor Williams having already departed for IBPGR.

In 1991, Brian was promoted to Senior Lecturer, Reader in 2004, and awarded a personal Chair in Plant Conservation Genetics in 2010. The School of Biological Sciences and the School of Biochemistry merged to form the School of Biosciences in 2000. Brian was Deputy Head of School from 2011 until his retirement in 2014, while concurrently serving as Director of the University Graduate School.

On completion of the MSc course in September 1971, I registered for a PhD under the supervision of potato taxonomist and genetic resources pioneer Professor Jack Hawkes, Mason Professor of Botany (who was also the MSc course leader) as a prelude to moving to Lima, Peru in January 1973 to continue my research at the International Potato Center (CIP). I returned to Birmingham to defend my dissertation in 1975, and my degree was awarded at a congregation in December.

Brian and I became colleagues in April 1981 when I returned to the UK after more than eight years with CIP in South and Central America, when I was appointed Lecturer in Plant Biology. I also took the reins as Short Course Tutor for genetic resources.

Given our departmental roles, and teaching commitments to MSc/Short Course students, and that we jointly taught a final year undergraduate module on genetic resources, it was natural that we would collaborate quite closely. We also both lived in the Worcestershire market town of Bromsgrove, some 13 miles south the university’s Edgbaston campus, and for the next decade we travelled together by car to and from the university almost every day. So we had ample opportunity to sound each other out on a range of topics, and it was during these that the idea of writing an introductory textbook took hold.

I left the university in June 1991 to join the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in the Philippines, as Head of the Genetic Resources Center (managing the world’s largest genebank for rice) and as Program Leader for Genetic Resources. I retired in 2010, returning to the UK. But in those intervening years, and afterwards, the collaboration between Brian and myself continued, as I will explain later.

Brian and I had a shared concern, as we explained in the first chapter of our book:

To most people the word ‘conservation’ conjures up visions of lovable cuddly animals like giant pandas on the verge of extinction. Or it refers to the prevention of the mass slaughter of endangered whale species, under threat because of human’s greed and short-sightedness. Comparatively few people however, are moved to action or financial contribution by the idea of economically important plant genes disappearing from the face of the earth. Precious orchid species with undoubted aesthetic appeal, or the vegetation of an Amazonian rain forest, where sheer vastness cannot fail to impress, may attract deserved attention. But plant genetic resources make little impression on the heart even though their disappearance could herald famine on a greater scale than ever seen before, leading to ultimate world-wide disaster (my emphasis).

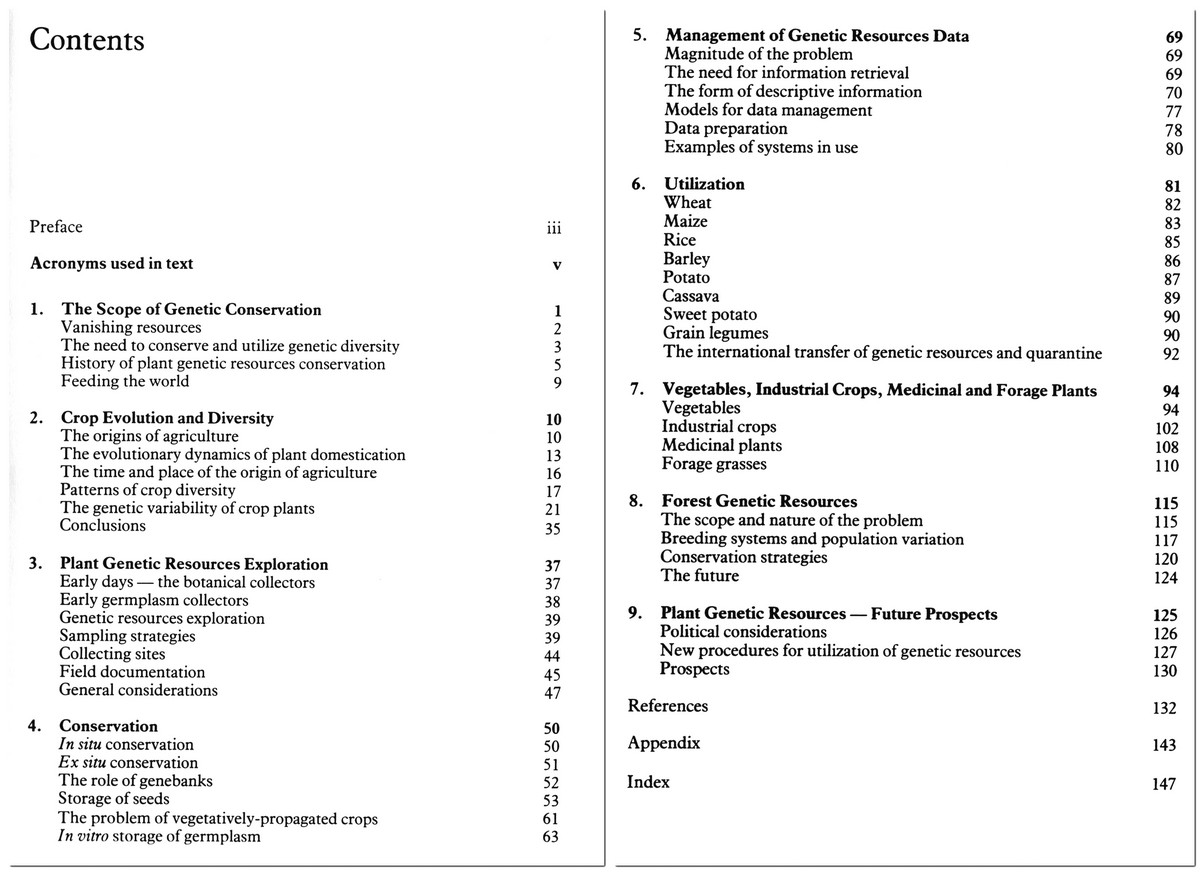

The book comprised just nine chapters, encompassing the scope of genetic conservation, the origins of agriculture and crop evolution, germplasm exploration, ex situ conservation of genetic resources in genebanks, and in situ in farmers’ fields, data management, uses of germplasm, forest genetic resources, and a gaze into the future, limited as that may have been. And, looking back over the past 40 years, perhaps our perspective was a little naïve and short-sighted. We had no crystal ball, however.

Just click on the image below for a list of chapters and content:

Obviously in a book of this length we could not delve into any single topic in great detail. That was not our intention. But, as a snapshot of what was current and possible 40 years ago it allowed readers to understand the why and wherefore of plant genetic resources and their conservation.

What’s perhaps more interesting is to review how the genetic resources landscape has changed over the past 40 years. I see there are two important issues.

The first is world population that, in 1986, numbered just under 5 billion mouths to feed. That’s now increased to 8.3 billion . . . and growing! Never has the need been greater or more urgent to use genetic resources to enhance crop productivity to feed a growing world population.

Second is the challenge of climate change, a topic we didn’t even address in 1986. But more about that below.

In our final Chapter 9, Future Prospects, we put forward a few ideas how things might change, including novel procedures such as biotechnology or wide crosses with wild species to utilise genetic resources (how limited I think we were in our thinking), and how the political landscape with regard to ownership and use of genetic resources was evolving.

And that political landscape changed beyond all imagination.

In December 1993 the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) came into force, a global treaty aimed at conserving biological diversity, promoting sustainable use of its components, and ensuring fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from genetic resources. It has two important protocols. The Cartagena Protocol (2003) on biosafety governs the movement of living modified organisms. The Nagoya Protocol (2014) is concerned with access and benefit sharing.

In December 1993 the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) came into force, a global treaty aimed at conserving biological diversity, promoting sustainable use of its components, and ensuring fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from genetic resources. It has two important protocols. The Cartagena Protocol (2003) on biosafety governs the movement of living modified organisms. The Nagoya Protocol (2014) is concerned with access and benefit sharing.

Then in 2004, the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture under the auspices of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) came into force. It is a legally binding international agreement that focuses specifically on conserving and sharing plant genetic resources essential for food and agriculture, with >150 members. It is consistent with the CBD but more specialised.

The Treaty has two important aspects:

- The Multilateral System of Access and Benefit-Sharing, which covers 64 major food and forage crops (e.g., rice, wheat, maize, potatoes); allows researchers, breeders, and farmers in member countries to access seeds and genetic material for research, breeding, and training; and requires benefit-sharing (e.g., funding, technology transfer) when commercial products are developed.

- The treaty explicitly recognizes Farmers’ Rights, which are farmers’ contributions to conserving and developing crop diversity; rights to save, use, exchange, and sell farm-saved seed (subject to national law); and participation in decision-making and benefit-sharing.

An enhanced genebank system, with those of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research or CGIAR continuing to play an important role, is meeting accepted international standards for conservation and increasingly supported (some like IRRI in perpetuity) through the Crop Trust that opened its doors in 2004. And at the hub, of course, is the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, opened in February 2008. Unfortunately international development assistance aid (that supports international agricultural research) has been cut back in many countries. Just look at the abolition of USAID by the Trump Administration in 2025. Even the British government has reduced its aid commitment.

An enhanced genebank system, with those of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research or CGIAR continuing to play an important role, is meeting accepted international standards for conservation and increasingly supported (some like IRRI in perpetuity) through the Crop Trust that opened its doors in 2004. And at the hub, of course, is the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, opened in February 2008. Unfortunately international development assistance aid (that supports international agricultural research) has been cut back in many countries. Just look at the abolition of USAID by the Trump Administration in 2025. Even the British government has reduced its aid commitment.

Progress in agricultural research (including the conservation and use of genetic resources) has been made because of what my former colleague and Director General of IRRI, Bob Zeigler, has called the Three Revolutions in:

- Telecommunications that allow international collaboration in real time.

- Computing and informatics that facilitate curation and analysis of large datasets, and development of genebank data management systems like GRIN-Global (an open-source software system and data platform designed to help plant genebanks store, organise, share, and publish information about plant genetic resources, and Genesys (a window on the world’s genebank collections).

- Molecular biology and genomics.

This last bullet is particularly significant, as rapid developments in these fields (which we had little or no inkling of the potential four decades ago) have opened so many insights as to the structure of genetic variation in crops and wild relatives, and how genes can be used for crop improvement. A revolution indeed! For an excellent introduction to how the various ‘omics’ of genetic resources could be used to respond to climate change, take a look at Ken McNally’s chapter [6]. Although published in 2014, it still is relevant today. Ken was a Senior Scientist at IRRI until his retirement earlier last year. He was a co-author of the 3000 rice genomes project.

Another area that was still in its infancy in the 1980s was cryopreservation of vegetatively-propagated species at the temperature of liquid nitrogen, although our colleague at Birmingham, Dr Graham Henshaw (later Professor at the University of Bath) was a pioneer in this area. Today, for example, CIP opened its Cryo-Facility in November 2024, the largest cryobank of its kind in Latin America.

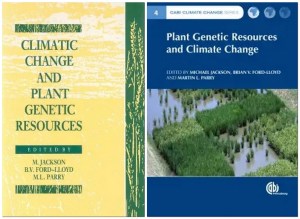

And talking of climate change, Brian and I organised a two -day meeting at Birmingham in 1989 on this topic, leading to the publication in 1990 of Climatic Change and Plant Genetic Resources [7], edited with our colleague from the Department of Geography, Professor Martin Parry. Then almost a quarter of a century later, CABI Publishing asked us to compile and edit an updated book on the same topic [8].

And talking of climate change, Brian and I organised a two -day meeting at Birmingham in 1989 on this topic, leading to the publication in 1990 of Climatic Change and Plant Genetic Resources [7], edited with our colleague from the Department of Geography, Professor Martin Parry. Then almost a quarter of a century later, CABI Publishing asked us to compile and edit an updated book on the same topic [8].

In this video we discussed how climate change science had moved on between publication of the two books.

And we don’t just discuss climate change in this interview but also how the conservation and use of plant genetic resources have evolved over the previous couple of decades.

After I left Birmingham in 1991, Dr Nigel Maxted (now Professor of Plant Genetic Conservation) was recruited in my stead. And he, Brian and others edited a series of books on ex situ and in situ conservation, and biotechnology [9, 10, 11], a couple of which I and my colleagues contributed to.

And the Birmingham group continued to publish several more texts [12, 13, 14, 15] that have influenced how this field of genetic conservation developed.

There are now two journals, Plant Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution (Springer, an English language continuation, from 1992, of Die Kulturpflanze that had been first published in East Germany in 1953) ) and Plant Genetic Resources – Characterization and Utilization (CUP) dedicated to the management and use of genetic resources.

During my tenure at IRRI, I continued to collaborate with Brian and his colleagues at the University of Birmingham (and at the John Innes Centre in Norwich), specifically studying the use of molecular markers to characterise and use rice genetic diversity. A list of all the publications can be found in this post.

During my tenure at IRRI, I continued to collaborate with Brian and his colleagues at the University of Birmingham (and at the John Innes Centre in Norwich), specifically studying the use of molecular markers to characterise and use rice genetic diversity. A list of all the publications can be found in this post.

Finally, during 2016-2017, Brian joined me (and Dra Maria José Borja Tome) in an external review that assessed the CGIAR’s Genebanks CGIAR Research Program (Genebanks CRP) — the system responsible for managing and conserving major crop genetic collections — as it transitioned into the Genebank Platform.

What started in 1969 with the launch of the MSc Course at The University of Birmingham was built upon by successive staff and students. The university has an enviable legacy in terms of teaching, research, and publishing widely about the conservation and use of plant genetic resources. I think it’s fair to claim that Plant Genetic Resources: an introduction to their conservation and use occupies a place in the pantheon of significant genetic resources literature.

What started in 1969 with the launch of the MSc Course at The University of Birmingham was built upon by successive staff and students. The university has an enviable legacy in terms of teaching, research, and publishing widely about the conservation and use of plant genetic resources. I think it’s fair to claim that Plant Genetic Resources: an introduction to their conservation and use occupies a place in the pantheon of significant genetic resources literature.

[1] Ford-Lloyd, BV and Jackson, MT. 1986. Plant Genetic Resources – an introduction to their conservation and use. Edward Arnold, London. Re-issued as a digitally-printed version by Cambridge University Press in 2010.

[2] Frankel, OH & Bennett, E. (eds.). 1970. Genetic resources in plants: Their exploration and conservation (IBP Handbook No. 11). Oxford & London: Blackwell Scientific Publications / International Biological Programme.

[3] Frankel, OH & Hawkes, JG. (eds.). 1975. Crop Genetic Resources for Today and Tomorrow. International Biological Programme Synthesis Series No. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[4] From its inception in 1969 until the early 2000s (when the taught course was replaced by MRes options), we estimate that more than 600 students from 150 countries attended the MSc and Short Courses on genetic resources.

[5] The International Board for Plant Genetic Resources (IBPGR) was established in June 1974 with support, and under the legal and administrative umbrella, of FAO. During the first ten years, IBPGR concentrated on collecting threatened crop genetic resources (including species in the mandates of other CGIAR Centres), setting up genebanks (including a number at the CGIAR Centres), developing standards (descriptors, etc.), providing training and supporting seed conservation research. From 1985 IBPGR gave increased attention to contract research and reduced its technical assistance to genebanks, while maintaining activities on collecting, developing standards and training. IBPGR worked increasingly in direct partnership with national programmes.

[6] McNally, K. 2014. Exploring ‘omics’ of genetic resources to mitigate the effects of climate change. In: Jackson, M, Ford-Lloyd, B and Parry, M. (eds). 2014. Plant genetic resources and climate change. 291 pp. CABI Publishing, Wallingford.

[7] Jackson, MT, Ford-Lloyd, BV and Parry, ML (eds). 1990. Climatic Change and Plant Genetic Resources. Belhaven Press, London.

[8] Jackson, M, Ford-Lloyd, B and Parry, M. (eds). 2014. Plant genetic resources and climate change. 291 pp. CABI Publishing, Wallingford.

[9] Hawkes, JG, Maxted, N and Ford-Lloyd, BV. 2000. The Ex Situ Conservation of Plant Genetic Resources. Kluwer, Dordrecht.

[10] Maxted, N, Ford-Lloyd, BV and Hawkes, JG (eds). 1997. Plant Genetic Conservation: The In-Situ Approach. Chapman and Hall.

[11] Callow, JA, Ford-Lloyd, BV, and Newbury, HJ. (eds). 1997. Biotechnology and Plant Genetic Resources. Biotechnology in Agriculture Series, no. 19. CAB International, Oxford.

[12] Stolton, S, Maxted, N, Ford-Lloyd, B, Kell, S and Dudley, N. 2006. Food Stores: Using protected areas to secure crop genetic diversity. A research report by WWF, Equilibrium and the University of Birmingham, UK. ISBN: 2-88085-272-2.

[13] Maxted, N, Ford-Lloyd, B.V, Kell, S.P, Iriondo, J, Dulloo, E and Turok, J. (eds.). 2008. Crop Wild Relative Conservation and Use. 682 pp. CABI Publishing, Wallingford.

[14] Maxted, N, Dulloo, ME, Ford-Lloyd, BV, Frese, L, Iriondo, J and Pinheiro de Carvalho. (eds). 2012. Agrobiodiversity Conservation. CABI, Wallingford, 353 pp.10.

[15] Maxted, N, Dulloo, M and Ford-Lloyd, B. (eds). 2016 Enhancing Crop Genepool use: Capturing Wild Relative and Landrace Diversity for Crop Improvement. CABI Publishing, Wallingford.