Two weeks ago, Steph and I had a four-day minibreak to visit my sister Margaret who lives in a small community west of Dunfermline in Fife, Scotland on the north side of the Firth of Forth.

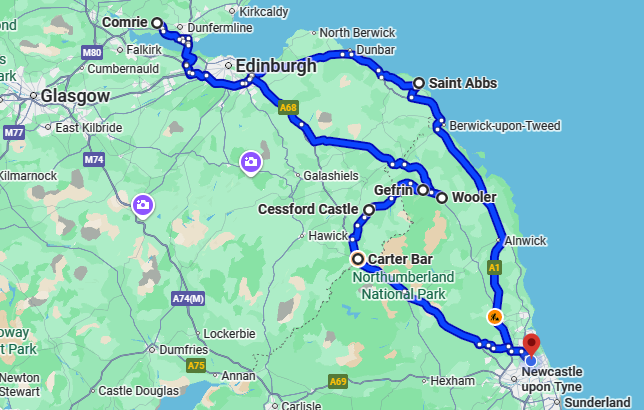

And we took advantage of that trip north to redeem—on the return journey—a couple of Christmas gift vouchers for a whisky distillery tour and tasting in the north Northumberland town of Wooler, then visiting several other localities along the Scottish border before returning home. The whole trip covered 376 miles.

On the Monday morning (6 October) we set off a little after 10 am, heading north on the A1. North of Berwick-upon-Tweed, the road runs close to the coast, and there are some lovely views over the North Sea, and further north still, views of the mouth of the Firth of Forth and Bass Rock, an important seabird colony particularly for gannets. We were very lucky with the weather more or less until we hit the Edinburgh By-Pass when it began to cloud over.

We broke the journey at St Abbs in the Scottish Borders, just 15 miles north of Berwick. We’d visited there once before. It’s an attractive small community with a harbour of fishing and dive boats. Dive boats? Yes, because the waters off St Abbs head nearby south to Eyemouth are a marine reserve, and attract many dry suit divers. But not for me, although I’m sure the diving could be spectacular. I learned to dive in the Philippines where the waters are considerably warmer.

Here is a short video of the drive down to St Abbs and views around the harbour and village.

We enjoyed a walk around the harbour, and had hoped to see something of the birdlife that the location is famous for. It was all quiet on the bird front – they must have all been hiding or out to sea.

After a spot of lunch, we headed back to the A1 and continued north to Comrie, arriving there about 15:30 just in time for a welcome cup of tea and a slice of lemon drizzle cake.

Our route took us around the Edinburgh By-Pass, and crossing the Firth of Forth on the ‘new’ Queensferry Crossing that carries the M90 motorway. The bridge opened to traffic on 30 August 2017. At 1.7 miles (2.7km) it is the longest 3-tower, cable-stayed bridge in the world, and replaced the Forth Road Bridge (which opened in 1964) and which now only carries buses, taxis, cyclists, and pedestrians. This link gives a potted history of these two bridges and the iconic rail bridge that opened in 1890.

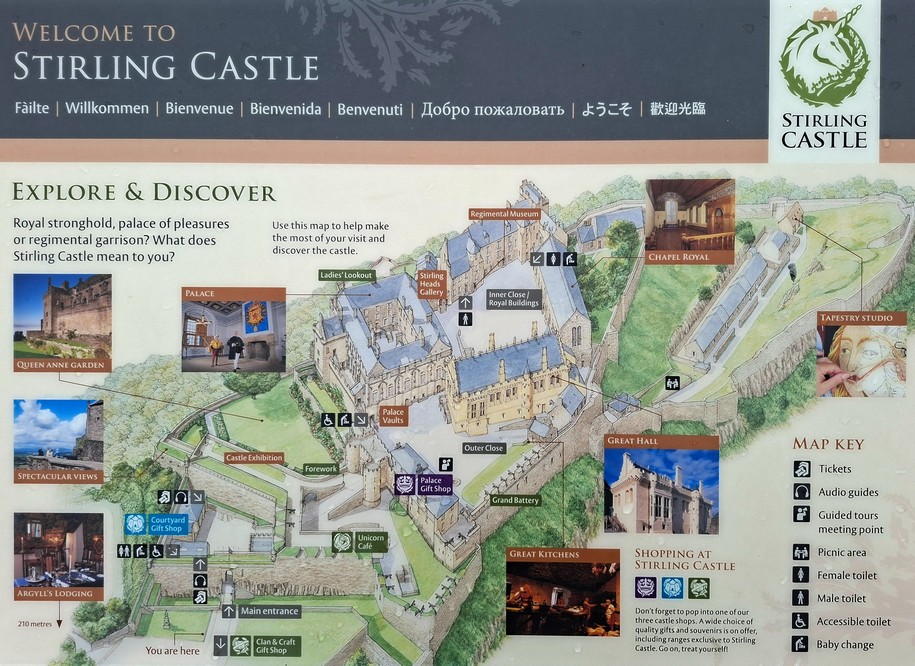

The next day, Margaret, Steph and me headed 18 miles west to visit Stirling Castle, owned by Historic Environment Scotland, and as we are long-standing members of English Heritage, we had free entry. The castle is perched high on a volcanic crag with impressive 360º views across the city and hills to the north.

The castle reached its zenith, as a renaissance royal palace, in the 1500s and was the home of King James V (right), father of Mary, Queen of Scots. Her son, James VI of Scotland and I of England (who Elizabeth I named as her heir in 1603) acceded to the Scottish throne (aged 13 months) in 1567, and spent much of his youth in this castle. The oldest part of the castle (the North Tower) dates from the 14th century; there were additions in the 18th century when the castle became a military stronghold.

The castle reached its zenith, as a renaissance royal palace, in the 1500s and was the home of King James V (right), father of Mary, Queen of Scots. Her son, James VI of Scotland and I of England (who Elizabeth I named as her heir in 1603) acceded to the Scottish throne (aged 13 months) in 1567, and spent much of his youth in this castle. The oldest part of the castle (the North Tower) dates from the 14th century; there were additions in the 18th century when the castle became a military stronghold.

Being mid-week, we didn’t think there would be many visitors, so booked our tickets for an 11:30 entrance. The car park was almost full, with coach after coach disgorging tourists from all corners of the globe. Fortunately, parking (at £5) was well-organized, and we were not permitted to drive into the carpark itself until parking marshals could direct us to a free space.

There’s certainly plenty to see at Stirling Castle, and by the time we ‘retired’ to have lunch, I was quite overwhelmed by all the information that I had tried to absorb.

There’s certainly plenty to see at Stirling Castle, and by the time we ‘retired’ to have lunch, I was quite overwhelmed by all the information that I had tried to absorb.

Outside the castle is an impressive statue of King Robert I, known as Robert the Bruce (1274-1329) whose particular claim to fame is his defeat of the forces of King Edward II of England at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314. What I had never realised until this visit to Stirling Castle is that the site of the battle is just 2 miles south.

There’s so much to see inside the castle walls, from Queen Anne’s Garden with its view over the surrounding landscape, the Royal Palace that has been luxuriously refurbished and newly fabricated tapestries hung, the Chapel Royal (built in 1594 by James VI for the baptism of his first-born Henry), and the Great Hall, one of the largest and finest in Europe.

A full set of photographs of our visit to Stirling Castle (and the other sites on our trip) can be viewed here.

By the time we left the castle around 14:00 the clouds had lifted and we could see all the way into the surrounding hills. So we headed to see an impressive landscape feature near Falkirk, just under 17 miles southeast of Stirling.

The Kelpies are to Falkirk what The Angel of the North is to Gateshead. So what are The Kelpies? Sitting beside the M9 motorway (from which we have glimpsed The Kelpies on previous occasions when passing by and always meaning to visit one day) and alongside the Forth and Clyde Canal, The Kelpies are large (very large) heads of mythical horses made from steel, standing 98 feet (or 30 m) high.

Designed by sculptor Andy Scott, they were completed in October 2013 and unveiled the following April to reflect the mythological transforming beasts possessing the strength and endurance of ten horses. The Kelpies represent the lineage of the heavy horse of Scottish industry and economy, pulling the wagons, ploughs, barges, and coal ships that shaped the geographical layout of the Falkirk area (Wikipedia). They are impressive indeed.

Our original idea was to visit The Kelpies the following morning as we left my sister’s to head south towards Wooler. Thank goodness our plans changed as the following morning we met heavy congestion south of the Queensferry Crossing, and crawled in traffic for about 10 miles, extending our journey by almost an hour. Consequently, we arrived in Wooler just after 1 pm and only 45 minutes before our distillery tour was due to begin.

The Ad Gefrin distillery was opened in 2023, but has not yet released its own whisky, although its warehouse is full of barrels ready for release as single malts by the end of 2026 or early the next year. For the time being it is retailing two whiskies—Corengyst and Tácnbora, branded as ‘blended in Northumberland’— made from Scottish and Irish whiskies.

We enjoyed the whisky tasting, and since Steph does not like the beverage, we took her samples home which I sampled again last week.

The distillery takes its name from the 7th century Anglo-Saxon settlement and royal palace of Gefrin, a few miles northwest of Wooler near the community of Yeavering, surrounded by hills in the vale of the  River Glen. There is a small museum dedicated to Gefrin at the distillery which we also had opportunity to view.

River Glen. There is a small museum dedicated to Gefrin at the distillery which we also had opportunity to view.

Then, next day after an excellent full English breakfast at the guesthouse where we stayed, we headed to Gefrin. And although there’s not a lot to see on the ground, there are several information boards explaining how the site was discovered in 1949 from aerial photographs, and subsequently excavated by Brian Hope-Taylor (right) between 1952 and 1962. Some of his interpretations remain problematical.

You can better appreciate the landscape around Gefrin in this video from about 3’30”.

We continued our journey west, crossing over the border back into Scotland near Morebattle before arriving at Cessford Castle, ancestral home of the Ker family (who became Dukes of Roxburghe) around 1450.

We continued our journey west, crossing over the border back into Scotland near Morebattle before arriving at Cessford Castle, ancestral home of the Ker family (who became Dukes of Roxburghe) around 1450.

The castle is unsafe to enter, but one can still appreciate its walls, 13 feet thick. It’s so isolated in its landscape, surrounded by a ditch that can still be appreciated to this day. As we walked around the ruin, we kept our eyes on a flock of sheep grazing nearby that I came to realise were actually rams, warily scrutinizing us.

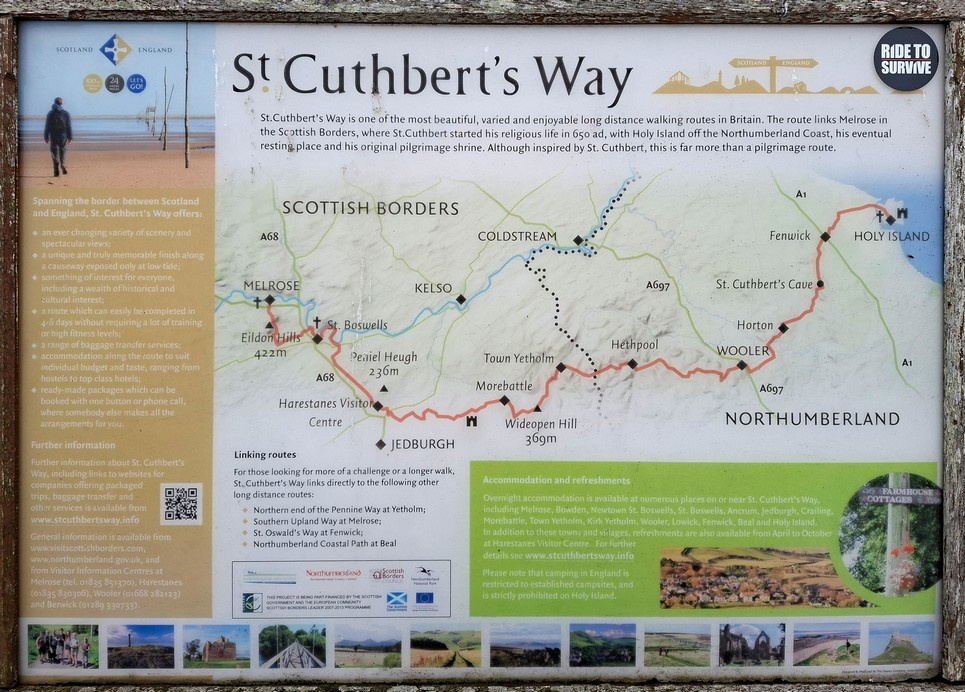

The route of St Cuthbert’s Way (from Holy Island on the Northumberland coast west to Melrose in the Scottish Borders) passes near the castle, and which we more or less followed for a while as we headed towards Jedburgh and the A68 that would take us over the border at Carter Bar back into England.

Carter Bar, at 1371 feet or 418 m, is the highest point on the pass in the Cheviot Hills, before crossing over into Redesdale on the England side. On a good day there must be a better view north into Scotland since we experienced low cloud cover. Nevertheless we still could appreciate the beauty of this location.

It has a long history in the relations between England and Scotland, and the Romans were here in the 1st century CE. Just a few miles away is Dere Street, a Roman road that we have encountered before at Chew Green, a Roman encampment close to the border but further south.

Then it was downhill all the way to North Tyneside, and it wasn’t far beyond Carter Bar that we were once again on familiar territory.

We must have been home by about 3 pm or so, just avoiding a major holdup less than a mile south from where we left the A19. A construction company had ruptured a mains water pipe and the road was flooded for several hours. I read that the diversions and traffic disruption were epic!

A couple of days ago, as Steph and I were driving—almost 23 years to the day since we first made this particular journey—up the narrow and twisting road to the headwaters of the

A couple of days ago, as Steph and I were driving—almost 23 years to the day since we first made this particular journey—up the narrow and twisting road to the headwaters of the