Steph and I returned recently from a very enjoyable week discovering ten National Trust (NT) and two English Heritage (EH) properties in Norfolk, Suffolk, and Cambridgeshire.

We’d booked this holiday way back in February, staying in a small cottage (The Bull Pen) on Hill Farm, Suffolk, 8 miles south of the market town of Diss (which lies just over the county boundary in Norfolk).

The Bull Pen was ideal for two people. A bit like Dr Who’s Tardis really, deceptively spacious inside.

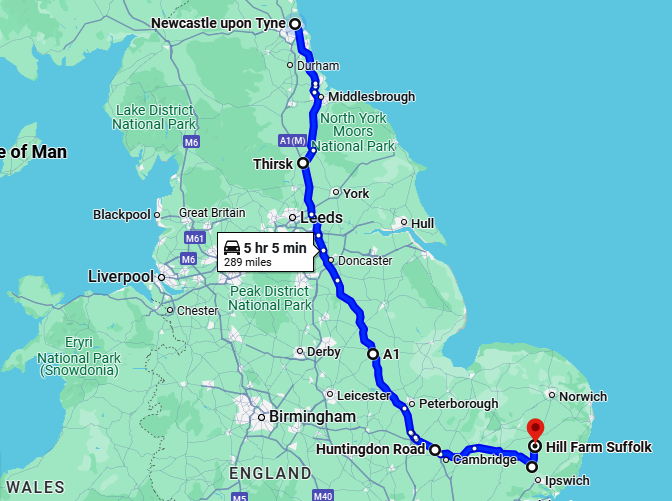

It was a long drive south from Newcastle: 289 miles door-to-door, on the A19, A1/A1(M), A14, and A140.

But we nearly didn’t get away at all. To my dismay, I discovered that the car battery had completely drained overnight. No power whatsoever! I have no idea how that happened.

Anyway, a quick call to the company that provides our maintenance and call-out contract, and a patrol man from the AA was with us by 08:30. Diagnosing a dead battery (but no other indicative faults) he fetched a new battery from a nearby depot, and we were on the road by about 09:45. Not too much of a delay, but with my wallet lighter by £230. Unfortunately, battery issues were not covered by our maintenance contract.

That wasn’t the end of our travel woes, as I will explain at the end of this post. On the way south (and on the return) we encountered significant hold-ups along the way. We finally reached our destination just before 17:00.

We had six full days to enjoy the 12 visits we made, two per day. Much as I enjoy the stunning architecture of the houses we visit, and the interior decoration and furnishings, it’s often the small details that I like to capture in my photography: a piece of porcelain, a detail on a fireplace, wallpapers (I’m obsessed with those since many have survived for 300 years), a particularly striking portrait, elaborate plasterwork on a ceiling, and the like. And these feature in the many NT and EH images I’ve accumulated over the past decade.

In the accounts below, I’ve highlighted some of the features that caught my attention. I’ve posted links to full photo albums in a list of properties at the end of this post.

And rather take up much online space providing comprehensive historical details, I’ve made links to the NT and EH websites where the property histories are set out in much more detail (and better than I could summarise).

7 September

We headed northwest into Norfolk to the Oxburgh Estate, passing the Neolithic flint mine site of Grime’s Graves on the way where flint was first mined almost 5000 years ago.

I’ve been to Grime’s Graves twice before. The first time was in July 1969 when, as a botany and geography undergraduate at the University of Southampton, I attended a two week ecology field course based at a community college near Norwich. The Breckland, with its sandy soils over chalk, has a special floral community, the reason for our visit. But while we were botanising we also took a look at this significant Neolithic site.

Grime’s Graves is dotted with the remains of numerous flint mine pits.

Then, around 1987, while we were holidaying in Norfolk, Steph and I took our daughters Hannah (then nine) and Philippa (five) to Grime’s Graves, where they descended the 9 m into one of the pits down a ladder to observe the mining galleries. How times have changed! Today, English Heritage has recently opened a custom-built staircase access to one of the pits, and descent to the depths is carefully monitored, hard hats and all. There is also a small visitor center with an interesting exhibition about the site and its history.

It’s fascinating to learn how our ancestors mined the valuable flint, using deer antlers to carve their way through the chalk, searching for the most valuable layers of flint at the deepest levels, and opening horizontal galleries at the pit bottom.

Then it was short journey on to the Oxburgh Estate, just 13 miles, where we arrived in time to enjoy a picnic lunch.

Home of the Catholic Bedingfield family for more than five centuries, Oxburgh is a beautiful moated mansion, built by the family in 1482. But obviously refurbished in various styles over subsequent centuries.

It has survived turbulent times, from the persecution of Catholics under Henry VIII and Elizabeth I, through the 17th century civil wars. The family still live there.

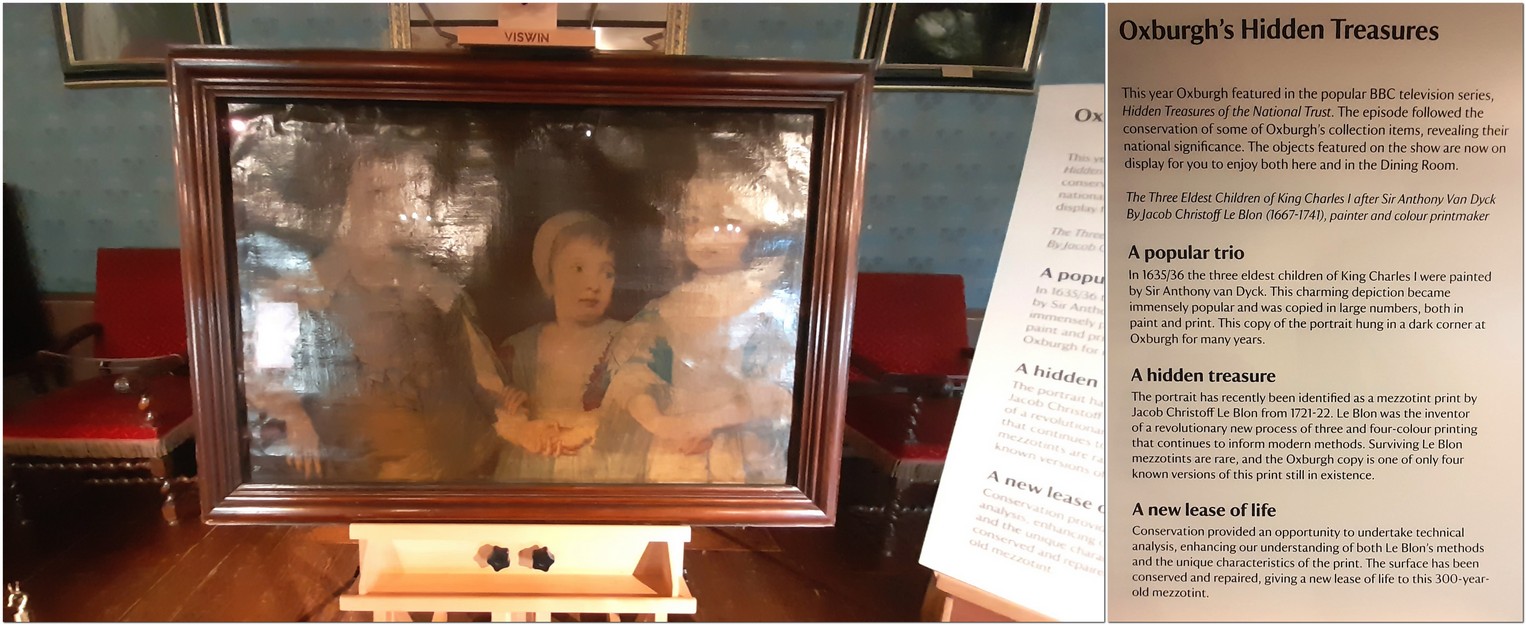

Oxburgh featured in a BBC series, Hidden Treasures of the National Trust. On display is a rare mezzotint print by Jacob Christoff Le Blon made around 1721/22, showing the three children of King Charles I, based on a painting of Sir Anthony Van Dyck. Click on the image below to enlarge.

Its significance had not been realised for a very long time, hidden away as it was in a dark corner at the bottom of a staircase.

Along some of the walls in upper floor corridors are a series of painted and embossed leather wallcoverings, sourced from antique markets around Europe in the early 19th century by the 6th baronet.

On display in one of the rooms are some exquisite silk embroideries created by Mary, Queen of Scots when in captivity at Hardwick Hall between 1569 and 1584. They came to Oxburgh in the late 18th century. It’s remarkable they are still in such good condition, although obviously very carefully conserved.

8 September

This was one of the longer journey days, almost to the north coast of Norfolk, to visit Blickling Hall and Felbrigg Hall.

I had a sharp intake of breath—of admiration (marred only slightly because one of the towers was covered in scaffolding)— when I first saw Blickling Hall, at the end of a long gravel drive, a stunning Jacobean mansion built in 1624.

There was an earlier Tudor house believed to be the birthplace of Anne Boleyn, second wife of Henry VIII (and mother of Elizabeth I).

This red brick mansion was built by Sir Henry Hobart (1560–1626) after he bought the estate in 1616. Seems like he enjoyed it for just a couple of years before his death. It passed through several generations of different families, eventually becoming the property of William Schomberg Robert Kerr, the 8th Marquess of Lothian (1832–1870), when he was just nine years old. It was during his tenure that many internal changes were made.

The 11th Marquess (right), Philip Kerr (1882-1940), Private Secretary to WW1 Prime Minister David Lloyd-George, and latterly UK Ambassador to the USA (where he died) and once a pro-Nazi Germany enthusiast, is however central to the story of the National Trust. Why? He was ‘the driving force behind the National Trust Act of 1937 and the creation of the Country Houses Scheme. This enabled the first large-scale transfer of mansion houses to the Trust in lieu of death duties, preserving some of the UK’s most beautiful buildings for everyone to enjoy, forever.‘

The 11th Marquess (right), Philip Kerr (1882-1940), Private Secretary to WW1 Prime Minister David Lloyd-George, and latterly UK Ambassador to the USA (where he died) and once a pro-Nazi Germany enthusiast, is however central to the story of the National Trust. Why? He was ‘the driving force behind the National Trust Act of 1937 and the creation of the Country Houses Scheme. This enabled the first large-scale transfer of mansion houses to the Trust in lieu of death duties, preserving some of the UK’s most beautiful buildings for everyone to enjoy, forever.‘

Inside the Hall there are some remarkable rooms, particularly the Long Gallery, which became a library in the 1740s.

What caught my particular attention? In the Lower Ante-Room, the walls are hung with two impressive Brussels tapestries (in the style of the paintings of David Teniers – probably the III) dating from around 1700. I was immediately drawn to the bagpiper in one of the tapestries.

Outside, the estate stretches to 4600 acres (1861 ha), but close to the house, we explored just the parterre, the temple and the Orangery.

Felbrigg Hall is only 10 miles north from Blickling. Originally Tudor, it was added to over the centuries. But it has a distinction not held by many NT properties. The last owner, Robert Wyndham Ketton-Cremer (right), commonly known as the Squire, inherited Felbrigg from his father. He devoted his life to preserving Felbrigg, finally bequeathing it [and all its contents] to the National Trust in 1969.

In 1442, the Felbrigg estate was bought by the Windhams of Norfolk, and remained in their hands until 1599 when it passed to Somerset Wyndham cousins, who adopted the Norfolk spelling of their surname.

The Jacobean front we see today was constructed between 1621 and 1624.

Felbrigg remained in the Windham family until 1863 when it was bought by wealthy Norwich merchant, John Ketton.

To the right of the entrance hall is the Morning Room (formerly the kitchen) with a fine set of paintings. Across the hall, is an elegant saloon, with a decorative ceiling, and fine marble busts, two them of arch political rivals from the late 18th/early 19th centuries: Tory William Pitt the Younger (1759-1806) and Whig Charles James Fox (1749-1806).

Fox (L) and Pitt (R)

In the Cabinet Room, full of treasures from the Grand Tour accumulated by William Windham II between 1749 and 1761, the ceiling has glorious plasterwork.

But for me the real treasure can be found in one of the upper floor rooms: Chinese silk wallpaper, from the 18th century.

The estate comprises 520 acres (211 ha), and a compact walled garden close to the house, with a impressive dovecote.

9 September

We headed southeast from our holiday cottage to take in two properties: Sutton Hoo (probably one of the most famous Anglo-Saxon burial sites in the UK if not Europe), and Flatford on the banks of the River Stour where landscape painter John Constable (1776-1837) painted some of his most famous works.

At Sutton Hoo, on land above the River Deben in southeast Suffolk, there is a group of royal burial mounds which have yielded some of the most remarkable Anglo-Saxon artefacts ever discovered, dating from around 625 BCE. One in particular must have been the burial of a rich and powerful king.

In the weeks leading up to the outbreak of war at the beginning of September 1939, local archaeologist Basil Brown uncovered a remarkable find on land owned by Edith Pretty.

Carefully scaping away the layers of sandy soil, the excavation team came across the shape of an 88 ft (27 m) ship within which was a remarkable Anglo-Saxon royal burial of incomparable richness, and [which] would revolutionise the understanding of early England. The treasures from Sutton Hoo are now carefully conserved in the British Museum, and further information can be found on the museum’s website.

Replicas (beautiful in their own right) are displayed in the exhibition at Sutton Hoo. What I had not realised was that the helmet that is the iconic image of Sutton Hoo (right) was made from steel (not silver as I had imagined), and found in 100 corroded pieces. It was carefully reconstructed, enabling artisans to replicate the helmet shown here.

Replicas (beautiful in their own right) are displayed in the exhibition at Sutton Hoo. What I had not realised was that the helmet that is the iconic image of Sutton Hoo (right) was made from steel (not silver as I had imagined), and found in 100 corroded pieces. It was carefully reconstructed, enabling artisans to replicate the helmet shown here.

On reflection, however, I guess I was rather disappointed by our visit to Sutton Hoo. Don’t get me wrong. It was fascinating, and being able to look over the burial mounds site from a tower was a bonus.

But I’d expected much more from Sutton Hoo, given the prominence it has received on the ‘heritage circuit’. I just had this feeling (which for NT properties is unusual for me) that they could have made more of the experience, and perhaps English Heritage would have made a better job of presenting Sutton Hoo’s story.

Then it was on to Flatford, a hamlet in the Dedham Vale close by East Bergholt where Constable was born. Many of his most famous landscape paintings were made around Flatford, including images of the River Stour, Willy Lott’s Cottage (as in The Hay Wain), and Flatford Mill itself.

As the day was quite overcast, and being the early afternoon, the number of visitors there was not high. I can imagine that at certain times of the year it must get awfully crowded. We were lucky. It was quite peaceful, and we could take in the atmosphere of the place. Several people were exercising their artistic talents, in attempts to interpret The Hay Wain.

10 September

Framlingham Castle was the home of the Bigod family (who came over with William the Conqueror in the Norman invasion of 1066), and the first timber fortress was constructed in 1086 by Roger Bigod, Sheriff of Norfolk. The first stone buildings date from the late 12th century.

Changing hands with, it seems, some regularity (as the Bigods were not always compliant with the king’s wishes), Framlingham eventually became the property of the Earls and Dukes of Norfolk for 400 years.

Mary Tudor was at Framlingham when she became queen in 1553.

Framlingham is unlike any other castle I have visited. Why? There never was a keep, just a curtain wall and 13 towers, enclosing a series of residential and administrative buildings. Protection was afforded to the castle by two very large defensive ditches.

In 1635, the castle was purchased by wealthy lawyer Sir Robert Hitcham, who left instructions in his will for the castle buildings to be demolished and a workhouse for local people built. The workhouse buildings are still standing.

English Heritage provides access to the castle walls, and visitors can make a complete circuit with some very fine views both internally and over the surrounding landscape that once provided a hunting park for the castle.

We really enjoyed our visit to Framlingham, and in the exhibition there’s a great animated video history of the castle (rather like the one we saw at Belsay Hall in Northumberland earlier this year).

In need of some sea air, we headed east to Dunwich Heath and Beach, just 16 miles. It’s a site of lowland heath, but when we visited the heather had more or less finished flowering. But the gorse species were still in full flower. So we made a walk of around 1½ miles, hoping to see some of the iconic birds that make Dunwich Heath their home, such as the Dartford warbler and stone curlew. It was very windy, and the only birds we encountered were a couple of pairs of stonechats.

We made it to the extensive beach. The Sizewell nuclear power stations site lies just under 3 miles south of Dunwich Heath.

11 September

This was the longest excursion we made during our holiday, a round trip of 137 miles to two proper near Cambridge: Anglesey Abbey and the Wimpole Estate.

Anglesey Abbey, a fine country house on the eastern fringes of Cambridge, had its origins in the 12th century under Henry I. The religious establishment was dissolved during the reign of Henry VIII in the 16th century, and at the beginning of the next, the Fowkes family that had acquired it some years earlier converted it to a family home. And it passed between various families over the next three centuries or so.

Until 1926, when the estate was bought by Urban Huttleston Broughton, 1st Baron Fairchild (right) and his brother Henry. Born in Massachusetts, their father was a British engineer who main a fortune in the USA in the railways, and who married the daughter of an oil tycoon Henry Huttleston Rogers, one of the world’s richest men. Fairchild and his brother inherited a huge fortune. No wonder they could afford the Anglesey Abbey estate (with Lode Mill), and refurbish and furnish it with treasures from around the world.

Until 1926, when the estate was bought by Urban Huttleston Broughton, 1st Baron Fairchild (right) and his brother Henry. Born in Massachusetts, their father was a British engineer who main a fortune in the USA in the railways, and who married the daughter of an oil tycoon Henry Huttleston Rogers, one of the world’s richest men. Fairchild and his brother inherited a huge fortune. No wonder they could afford the Anglesey Abbey estate (with Lode Mill), and refurbish and furnish it with treasures from around the world.

Having enjoyed an excellent cup of coffee in what seemed to be quite a new Visitor Centre, we headed off into the grounds, towards Lode Mill, and the various gardens (Walled, Dahlia, and Rose) that Fairchild had laid out. I’ve never seen so many statues in one place before.

After enjoying a slow stroll there, we went indoors where only two main rooms on the ground floor were open plus the dining room. Renovations upstairs had closed that part of the house to the public.

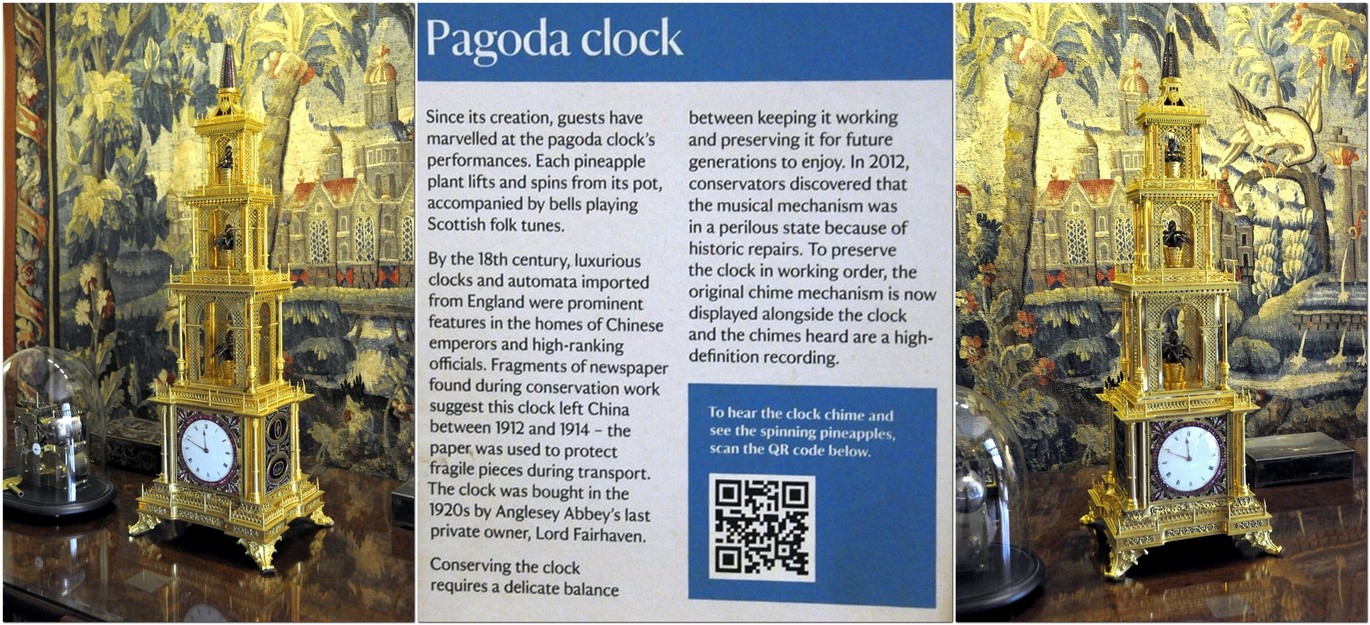

In the Living Room there is a remarkable clock, which also featured in one of the BBC series about hidden treasures, and attributed to James Cox (1723-1800). Click on the image below to enlarge.

After lunch we headed southwest to the Wimpole Estate (comprising some 3000 acres or 1215 ha), where there has been settlements for 2000 years from Roman times.

The large mansion that we see today was begun in 1640, and has been the home of many families over the centuries.

We arrived there just before the heavens opened, and took shelter in the Visitor Centre before making our way up to the hall itself and on to the walled garden, one of the biggest and best that I have seen at many NT properties.

In the last decade of the 19th century, Wimpole was acquired by Lord Robartes, 6th Viscount Clifden, who settled the estate on his son Gerald in 1906. Also owning Lanhydrock in Cornwall (another NT property we visited in 2018), the 7th Viscount was unable to afford the upkeep of both, and put Wimpole up for sale.

From 1938 Wimpole was first rented and then bought by Captain and Mrs Bambridge (right). After the Captain’s death Mrs Bambridge continued to live at Wimpole, and bequeathed the property and contents to the NT on her death in 1976.

From 1938 Wimpole was first rented and then bought by Captain and Mrs Bambridge (right). After the Captain’s death Mrs Bambridge continued to live at Wimpole, and bequeathed the property and contents to the NT on her death in 1976.

The house was essentially empty when the Bambridges took on Wimpole. One NT volunteer told us that just a pair of sofas in the Yellow Drawing Room were the only items left behind.

So how did the Bambridges not only acquire Wimpole but have the resources to refurbish and furnish it with some priceless treasures that fill every room? Mrs Elsie Bambridge (1896-1976) was the younger daughter of novelist and Nobel Laureate in Literature, Rudyard Kipling, and the only one of three siblings to survive beyond early adulthood. Kipling lived at Bateman’s in East Sussex that we visited in May 2019.

Just take a look at the photo album at the end of the post to appreciate just what it must have cost to turn Wimpole into the home that Mrs. Bambridge enjoyed for several decades.

12 September

This was our final excursion, to two properties, Ickworth Estate (1800 acres or 730 ha) and Melford Hall, south of Bury St Edmunds in Suffolk.

Ickworth was mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086. It came into the Hervey (pronounced ‘Harvey’) family in 1460, and remained with them for the next five centuries.

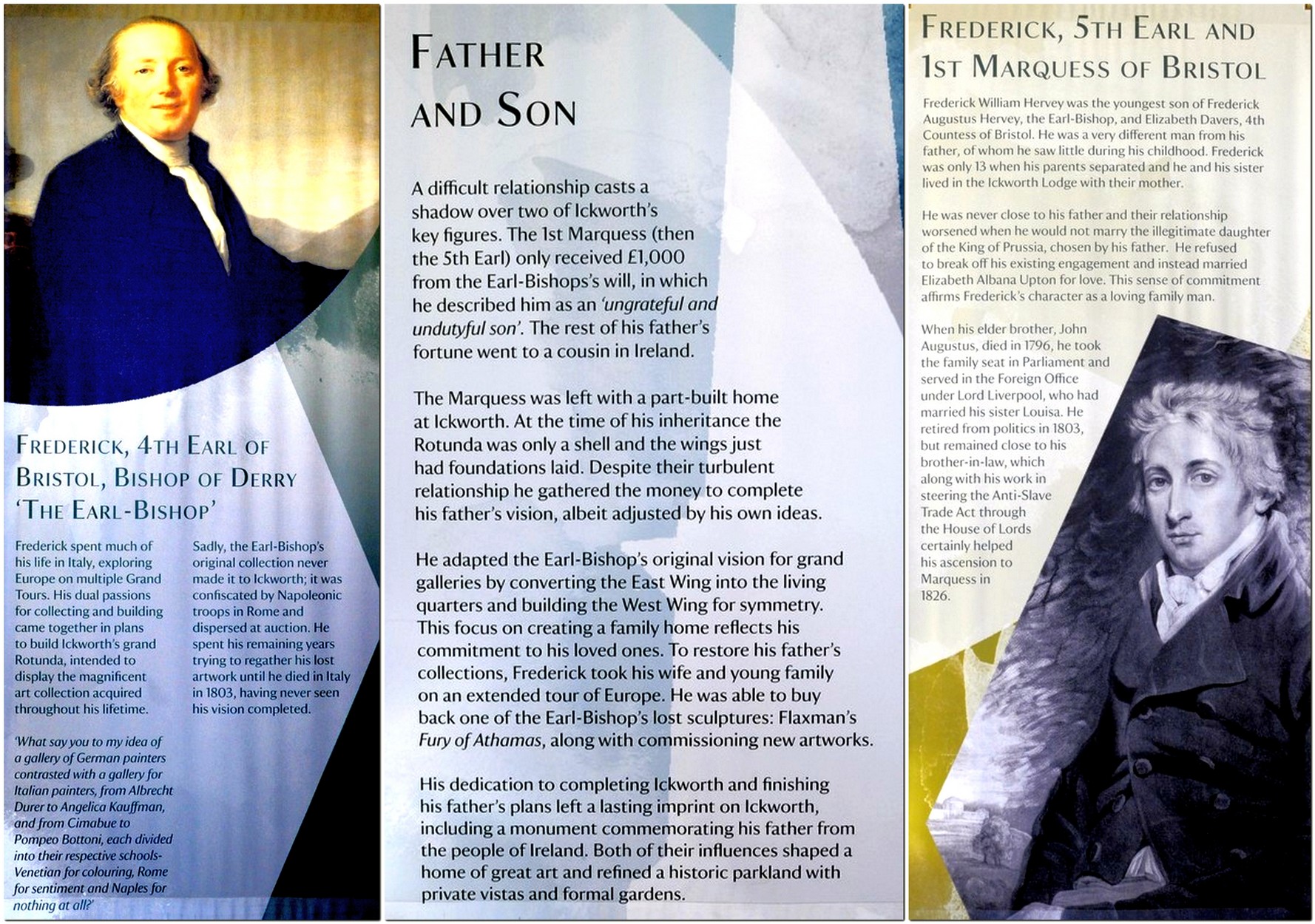

In 1700, Ickworth was inherited by John Hervey who became the 1st Earl of Bristol. The house we see today was completed by Frederick, the 5th Earl (later to become the 1st Marquess of Bristol), thus fulfilling the vision of his father, the 4th Earl and Bishop of Derry in Northern Ireland. Click on the image below to enlarge.

Before heading into the house, we took a long walk down to the walled garden (where a large wild flower meadow had been sown) and then to St Mary’s Church where members of the Hervey family are buried. The 4th Marquess bequeathed Ickworth to the Treasury in 1956 in lieu of death duties (and it was then passed to the National Trust, ref. my earlier comment about the National Trust Act of 1937).

The 7th Marquess (1954-1999) inherited a fortune 1985, occupying an apartment in the house on a 99 year lease. However, he frittered his inheritance away on a very flamboyant lifestyle, to say the least, and sold the lease to the NT which now wholly owns Ickworth. The East Wing has been a luxury hotel since 2002.

Melford Hall is a 16th century mansion some 13 miles south from Ickford. It’s not known with certainty who actually built the hall. It has been the home of the distinguished naval Hyde Parker family since 1786, and the 13th Baronet and his family continue to live in the South Wing.

We enjoyed wandering round the small garden surrounding the hall (there is a larger park) before exploring just the North Wing of the house. There was a significant fire there in 1942 but that was successfully repaired without having to demolish any other parts of the building.

Famous writer, illustrator and famed mycologist Beatrix Potter was a distant relation of the Hyde Parkers, and often stayed at Melford from 1890 onwards. Her bedroom is open to view and a number of her illustrations (including one of a mouse in her bed there) are displayed around the house.

And that was the last of our visits. What an enjoyable week, getting to know a part of England that we’ve hardly visited before. All was left was the long journey home. Driving in this part of the country was no joy. Such heavy traffic and congested roads. I wasn’t looking forward to the return journey north, but as I’d already worked out a diversion around that earlier hold-up in West/North Yorkshire on the way down, I was hopeful of a trouble-free trip back home. Unfortunately that wasn’t to be the case, as you can read below.

However, do take a look at the photo albums below to appreciate the beauty of the properties we visited over six days. Truly a travel through time across the east of England.

Photo albums

- Grime’s Graves

- Oxburgh Estate

- Blickling Estate

- Felbrigg Hall

- Sutton Hoo

- Flatford

- Framlingham Castle

- Dunwich Heath and Beach

- Anglesey Abbey

- Wimpole Estate

- Ickworth

- Melford Hall

The journey

Once our battery problem had been sorted, we set off around 09:45, heading south on the A19 and made good time reaching the services at Wetherby just over an hour later. A quick comfort stop and a coffee and we set off again. Just as the A1(M) downgraded to a dual carriageway A1 south of Ferrybridge we hit stationary traffic, and then took around an hour to crawl through roadworks where a bridge was being repaired on the northbound carriageway. Traffic was backed up at least 5 miles in each direction.

That was our main holdup heading south, just some slower traffic around Huntingdon and Cambridge, but not really something to write home about.

Having experienced that hold-up near Ferrybridge, I decided to look for an alternative route for the return, and found that I could join the M18 eastbound south of the roadworks, skirt Doncaster in its inner ring road, and join the M62 west which would bring us on to the A1(M) north of the roadworks.

But on the return journey we hadn’t expected the unexpected. Around 10:30, on the A1 near Stamford in Lincolnshire, we ground to a halt, and after about 10 minutes my satnav advised a diversion at the next exit, just 100 m ahead. Which I took. So did others. And we found ourselves crawling through the town center, cars parked on both sides of the street, and huge articulated trucks heading north and south trying to pass each other. The town went into gridlock, and it took more than an hour to reach the north side of the town and re-join the A1.

I later discovered that the A1 had remained closed for the next 6 hours, and the traffic backed up at least 10 miles in both directions. A woman had fallen, jumped, or been pushed (?) from a bridge, and died. The site became a potential crime scene, so the police closed the road completely, eventually redirecting traffic through other diversions. One hour through Stamford was frustrating, but nothing compared to being stuck on the A1 as so many others were.

We encountered several other serious hold-ups further north, and had to make three more diversions, arriving home just after 5 pm. What a journey, and certainly a disappointment after such a glorious week in East Anglia.