Last week, Steph and I spent three days exploring five National Trust and English Heritage properties in Lincolnshire and Cambridgeshire. This is not an area with which we are familiar at all. We spent the first night on the coast at Skegness, and the second in the Georgian town of Wisbech.

It was a round trip of just under 360 miles from our home in Bromsgrove, taking in nine counties: Worcestershire, West Midlands, Warwickshire, Leicestershire, Nottinghamshire, Lincolnshire, Cambridgeshire, Norfolk (for about three minutes), and Rutland.

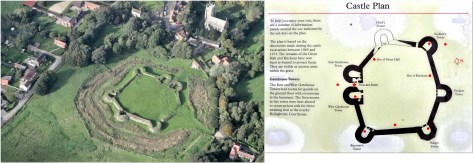

Our first stop was Tattershall Castle in Lincolnshire. There has been a fortified residence on this site since the mid thirteenth century, but it wasn’t until two centuries later that the remarkable brick tower was built. This is quite unusual for any castle, and Lord Cromwell is believed to have seen such buildings during his sojourns in France.

The tower and part of a stable block are all that remain today, although the position of other towers and a curtain wall can be seen. The whole is surrounded by a double moat.

Like so many other castles (see my blogs about Goodrich Castle in Gloucestershire, Corfe Castle in Dorset, and Kenilworth in Warwickshire) Tattershall was partially demolished (or slighted) during the Civil Wars between 1642 and 1651.

And over the subsequent centuries it slipped into decay. Until the 1920s when a remarkable man, Viscount Curzon of Kedleston (near Derby) bought Tattershall Castle with the aim of restoring it to some of its former glory, the magnificent tower that we see today.

The castle was then gifted to the National Trust in whose capable hands it has since been managed.

There is access to the roof (and the various chambers on the second and third floors) via a beautiful spiral stone staircase, quite wide by the normal standard of such staircases. But what makes this one so special is the carved handrail from single blocks of stone. And on some, among all the other centuries-old graffitti, are the signatures of some of the stonemasons.

Do take a look at this album of photos of Tattershall Castle.

Just a mile or so southeast of the castle is RAF Coningsby, very much in evidence because it’s a base for the RAF’s Typhoon aircraft, and a training station for Typhoon pilots. So the noise from these aircraft is more or less constant. However, RAF Coningsby is also the base for the Battle of Britain Memorial Flight, and just as we reached the car park on leaving Tattershall, we were treated to the sight of a Lancaster bomber (the iconic stalwart of the Second World War Bomber Command) passing overhead, having just taken off from the airfield, just like in the video below. At first, it was hidden behind some trees, but from the roar of its engines I knew it was something special. Then it came into view while banking away to the east.

Just 20 miles further east lies Gunby Hall, a William and Mary townhouse masquerading as a country house, and built in 1700. The architect is not known.

It was built by Sir William Massingberd (the Massingberds were an old Lincolnshire family) and was home to generations of Massingberds until the 1960s. You can read an interesting potted history of the family here.

Gunby Hall, and almost all its contents accumulated by the Massingberds over 250 years were gifted to the National Trust in 1944. Lady Diana Montgomery-Massingberd (daughter of campaigner Emily Langton Massingberd) was the last family member to reside at Gunby, and after her death in 1963, tenants moved in until 2012 when the National Trust took over full management of the house, gardens and estate.

Gunby is remarkable for two things. During the Second World War, the house was in great danger of being demolished by the Air Ministry because the runway at nearby (but now closed) RAF Spilsby had to be extended to accommodate the heavy bombers that would operate from there. But Sir Archibald Montgomery-Massingberd (husband of Lady Diana) was not a man without influence. He had risen to the rank of Field Marshal, and had served as Chief of the Imperial General Staff between 1933 and 1936. After he wrote to the king, George V, the location of the runway was changed, and Gunby saved.

It was then decided to gift the property and contents to the National Trust. So what we see in the house today is all original (nothing has been brought in from other properties or museums).

Sir Archibald Montgomery-Massingberd started life a simply Archibald Montgomery, but changed his name by deed poll to Montgomery-Massingberd on his marriage to Diana. It was a condition of the inheritance of the estate that the name Massingberd was perpetuated. Both he and Diana are buried in the nearby St Peter’s Church on the edge of the gardens.

Although not extensive, Steph and I thought that the gardens at Gunby were among the finest we have seen at any National Trust property. Yes, we visited in mid-summer when the gardens were at their finest perhaps, but the layout and attention to detail from the gardeners was outstanding. Overall the National Trust volunteers were knowledgeable and very friendly. All in all, it was a delightful visit.

You can see more photos here.

On the second day, we headed west from our overnight stay in Skegness on the coast (not somewhere I really want to visit again), passing by the entrance to Gunby Hall, en route to Bolingbroke Castle, a ruined castle owned by English Heritage, and birthplace of King Henry IV in 1367, founder of the Lancaster Plantagenets.

There’s not really too much to see of the castle except the foundations of the various towers and curtain wall. Nevertheless, a visit to Bolingbroke Castle is fascinating because English Heritage has placed so many interesting information boards around the site explaining the various constructions, and providing artist impressions of what the castle must have looked like.

So the castle footprint is really quite extensive, surrounded by a moat (now just a swampy ditch) that you can walk around, inside and out, taking in just how the castle was built.

A local sandstone, rather soft and crumbly, was used and couldn’t have withstood a prolonged siege. Interspersed in the walls, now revealed by deep holes but still in situ elsewhere, are blocks of hard limestone that were perhaps used for ornamentation as well as giving the walls additional strength. The castle was slighted in the Civil Wars of the 1640s.

The complete set of Bolingbroke photos can be viewed here.

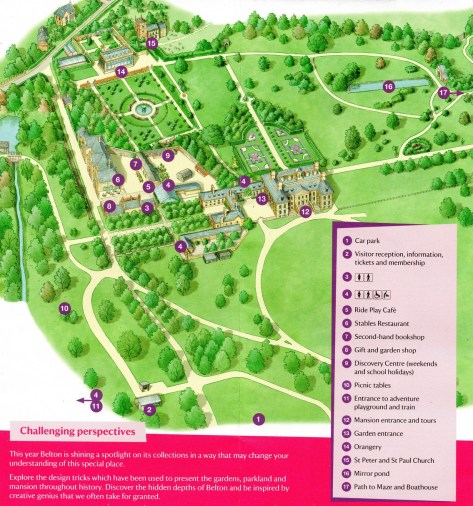

Heading south to Wisbech, our aim was Peckover House and Garden, occupied from the 1770s until the late 1940s by the Peckover family of Quakers and bankers.

Peckover House is a detached Georgian mansion, among a terrace of elegant houses on North Brink, the north bank of the tidal River Nene, and facing a counterpart terrace on South Brink, where social reformer Octavia Hill, one of the founders of the National Trust, was born in 1838.

Standing in front of Peckover House, it’s hard to believe that there is a two acre garden behind. Among the features there is a cats’ graveyard of many of the feline friends that have called Peckover home.

Inside the house, I was reminded (though on a much smaller scale) of Florence Court in Northern Ireland that we visited in 2017. The hall and stairs are a delicate duck-egg blue, and there and in many of the rooms there is exquisite plasterwork. Above the doorways downstairs are fine broken pediments.

The most celebrated of the family was Alexander (born in 1830) who traveled extensively and built an impressive collection of books and paintings. He was Lord Lieutenant of Cambridgeshire, and was elevated to a peerage in 1907.

The most celebrated of the family was Alexander (born in 1830) who traveled extensively and built an impressive collection of books and paintings. He was Lord Lieutenant of Cambridgeshire, and was elevated to a peerage in 1907.

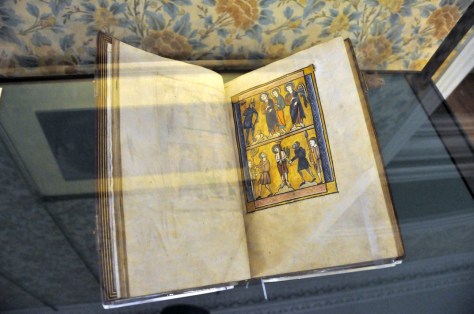

He bought one of his books, a 12th century psalter, in about 1920 for £200 or so. Now on loan from Burnley library and displayed in Alexander’s library, the book has been insured for £1,200,000!

Check out more photos of Peckover House and garden.

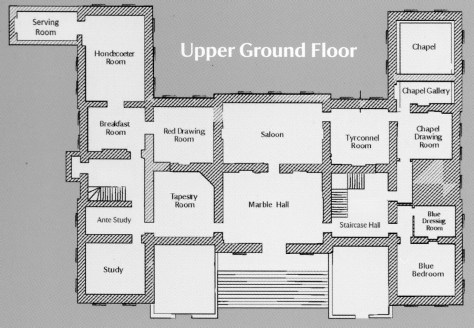

Our final stop, on the way home on the third day, was Woolsthorpe Manor, birthplace of Sir Isaac Newton, President of the Royal Society, who was born on Christmas Day in 1642 three months after his father, also named Isaac, had passed away.

This is the second home of a famous scientist we have visited in the past couple of months, the first being Down House in Kent, home of Charles Darwin. Woolsthorpe has become a pilgrimage destination for many renowned scientists, including Albert Einstein and Stephen Hawking who are shown in some of the exhibits.

Woolsthorpe is not a large property, comprising a limestone house and outbuildings. It has the most wonderful tiled roof.

It came into the Newton family as part of the dowry of Isaac Sr.’s marriage to Hannah Ayscough. Keeping sheep for wool production was the principal occupation of the family.

Isaac Newton won a place at Trinity College, Cambridge but had to escape back to Woolsthorpe during an outbreak of the plague in 1665 and 1666. He thrived and the 18 months he spent at Woolsthorpe were among his most productive.

Open to the public on the upper floor, Newton’s study-bedroom displays his work on light that he conducted there.

And from the window is a view over the orchard and the famous Flower of Kent apple tree that inspired his views on gravitation.

On the ground floor, in the parlour are two portraits of Newton, one of him in later life without his characteristic wig, and, high above the fireplace, his death mask.

Also there are early copies (in Latin and English) of his principal scientific work, the Principia Mathematica, first published in 1687.

There’s a full album of photos here.

And, with the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11 and the first landing on the Moon on 20 July 1969, there was a display of NASA exhibits and how Newton’s work all those centuries ago provided the mathematical basis for planning a journey into space. The National Trust has also opened an excellent interactive science display based on Newton’s work that would keep any child occupied for hours. I’m publishing this post on the anniversary of Apollo 11’s blast off from Cape Kennedy, now Cape Canaveral once again.

And, with the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11 and the first landing on the Moon on 20 July 1969, there was a display of NASA exhibits and how Newton’s work all those centuries ago provided the mathematical basis for planning a journey into space. The National Trust has also opened an excellent interactive science display based on Newton’s work that would keep any child occupied for hours. I’m publishing this post on the anniversary of Apollo 11’s blast off from Cape Kennedy, now Cape Canaveral once again.

All in all, we enjoyed three excellent days visiting five properties. Despite the weather forecast before we set out, we only had a few minutes rain (when we arrived at Bolingbroke Castle). At each of the four National Trust properties the volunteer staff were so friendly and helpful, full of details that they were so willing to share. If you ever get a chance, do take a couple of days to visit these eastern England jewels.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

* The Lincolnshire Wolds are a range of hills, comprised of chalk, limestone, and sandstone. The Fens are drained marshlands and a very important agricultural region.