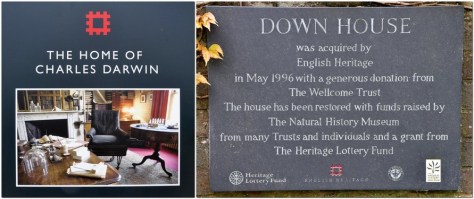

It is clear from our recent visit to Down House in Kent, the Georgian manor that Charles and Emma Darwin called home for 40 years until his death in 1882, that Darwin certainly did discover the value of life.

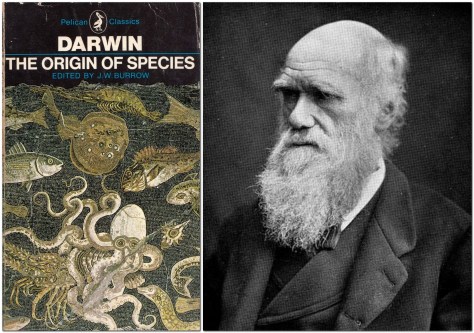

Charles Darwin, naturalist and confirmed agnostic, turned the world upside down in 1859 with the publication of his seminal On the Origin of Species, published to great claim, and controversy. It was written at Down House as was much of his prolific output.

Born in Shrewsbury in 1809, the son of a doctor and successful businessman, Robert Darwin, he had two illustrious grandfathers: natural philosopher Erasmus Darwin, and potter Josiah Wedgwood, both anti-slavery abolitionists and members of the Lunar Society of Birmingham. Darwin never knew his grandfathers, as both passed away before his birth.

Coming from a wealthy background and supported by his father and the Wedgwoods, Darwin had no need to find other employment. He could concentrate on developing his theories and publishing his ideas. He did not have to sell many of his precious specimens as was often the case for many naturalists like Darwin’s ‘rival’ Alfred Russel Wallace, for example, to keep body and soul together. Many items of Darwin memorabilia are on display at Down House today.

Darwin married his first cousin Emma Wedgwood in January 1839, and over the next seventeen years had ten children. Moving from a cramped house in London in September 1842, Down House was the ideal location for the Darwins to raise their growing family, and for Darwin himself to have the space and tranquility to develop his theories on evolution and natural selection.

When they moved to Down House, the Darwin’s were already the proud parents of a son, William (b. 1839) and a daughter Anne (b. 1841). Another daughter, Mary was born at the time of the move, but lived for less than a month. Their last child, Charles W. (b. 1856), died in infancy aged 18 months. Anne succumbed to tuberculosis in 1851.

Our visit to Down House was the first stop in a recent week-long break in the southeast. From home in northeast Worcestershire to Down House is a journey of 156 miles, under three hours by road, almost entirely on motorways (M42-M40-M25). Leaving the M25 at Junction 4, we took to the narrow lanes to cut across country to the Kent village of Downe.

Just four rooms are open to the public on the ground floor: Darwin’s Study (one can stand there in awe), the Dining Room (that Darwin, as a local Justice of the Peace, used as his court room), the Billiard Room, and the Parlour. No photography is permitted inside the house because all the items on display still belong to the Darwin family.

In the Dining Room there are two fine oil paintings of grandfather Erasmus. The porcelain on the dining table must surely be Wedgwood?

On the first floor (there’s no access to the upper floor) several rooms are filled with Darwin memorabilia, his journals, awards and the like. It’s a snapshot of Darwin’s life. One room was filled with wood engravings by Darwin’s granddaughter Gwen Raverat.

Another room, supposedly the Darwin’s bedroom, with a magnificent bow-window view over the garden, has been reconstructed by English Heritage, and photography is permitted there.

Down House has quite modest grounds, including an orchard. In the walled garden where Darwin conducted many of his experiments, the lean-to greenhouse has a small but fine collection of carnivorous plants and orchids.

At the far end of the garden, and parallel to the house and terrace, is the Sandwalk, a gravel path where Darwin (a creature of habit) would take a walk every day and work through all the ideas swirling around his mind. It’s not hard to imagine Darwin strolling along the Sandwalk.

As an evolutionary biologist who has worked on the variation in domesticated plants and in nature (addressed by Darwin in Chapters 1 and 2 of his On the Origin of Species) in potato and rice and their wild species relatives for much of my career, I had long been looking forward to this visit to Down House.

And I was both pleased and disappointed at the same time. It was incredible to see where Darwin had lived, and formulated one of the most important scientific theories ever, to see his journals and many other personal items, to learn something about his family and family life. Darwin often suffered from ill health, almost considered a hypochondriac. Now it’s thought that he may have been suffering from recurring bouts of Chagas disease that he picked up in South America during his voyage there on HMS Beagle.

On the other hand, I came away feeling that something had been missing. I didn’t feel much emotional connection to Down House as I have experienced in visits to other properties (such as Chartwell or Bateman’s, to mention just a couple). I know Darwin had lived in Down House. There was all the evidence in front of me. It just didn’t feel as though he had.

I mentioned that photography is not permitted inside Down House. Visitors are greeted at the entrance with a sign stating that photography is prohibited. Prohibited! Perhaps English Heritage could tone down the ‘request’. A more welcoming approach would be more appropriate.

Before visiting Down House, I decided to re-read On the Origin of Species, which I had first read many decades ago. I didn’t make good progress. It’s not that the subject matter is difficult. After all, Darwin’s ideas were ‘meat and potatoes’ to me during my working life. It’s just that Darwin’s style of writing is challenging, not helped by an extremely small font in the version I have. I’ll get there, eventually.