Have you ever visited the northeast of England? The ancient Kingdom of Northumbria. If not, why not? We think the northeast is one of the most awe-inspiring regions of the country.

My wife and I moved here, just east of Newcastle upon Tyne, in October 2020 at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic. Newcastle is the largest city in the northeast, on the north bank of the River Tyne (seen in this video from the Gateshead south bank) with its many iconic bridges, and the Glasshouse International Centre for Music on the left (formerly Sage Gateshead, known locally as The Slug).

We visited Northumberland for the first in the summer of 1998 when home on leave from the Philippines, never once contemplating that we’d actually be living here 22 years later. We have been regular visitors to the northeast since 2000 when our younger daughter Philippa began her undergraduate studies at Durham University, and she has remained in the northeast ever since.

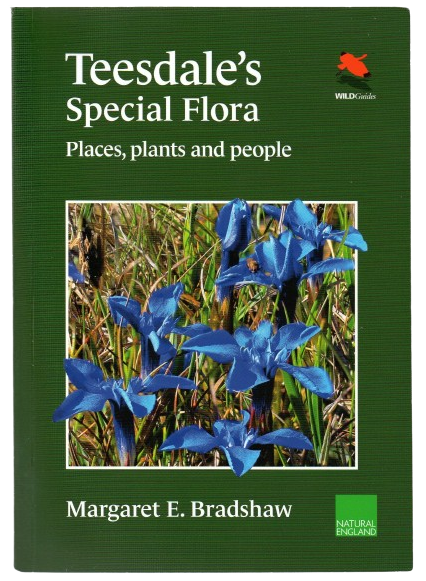

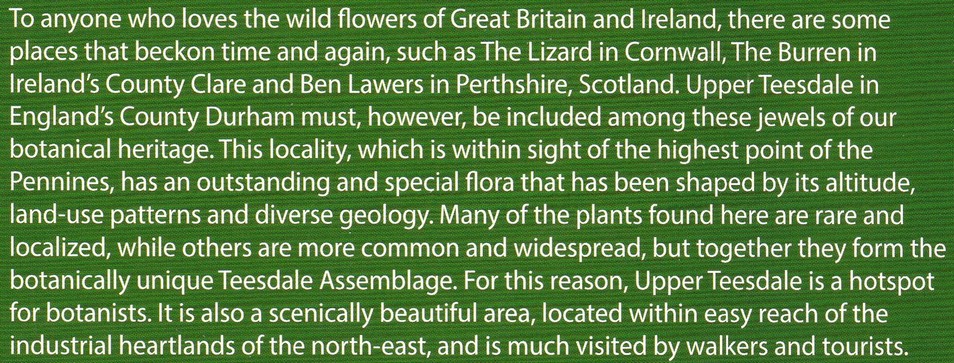

Northumbria has it all: hills, moorlands, river valleys, beaches and, to cap it all, a rich history and lively culture. There are so many glorious landscapes to enjoy: the Northumberland National Park stretching to the border with Scotland; the dales and uplands of the North Pennines National Landscape in Durham and North Yorkshire, as well as the North York Moors a little further south. And all easily accessible from home. Here’s just a small sample.

On this map I have pinpointed all places we have visited since October 2020 (and a couple from earlier years), several places multiple times. Do explore by clicking on the ![]() expansion box (illustrated right) in the map’s top right-hand corner. I have grouped all the sites into different color-coded categories such as landscapes, coast, Roman sites, religious sites, and castles, etc.

expansion box (illustrated right) in the map’s top right-hand corner. I have grouped all the sites into different color-coded categories such as landscapes, coast, Roman sites, religious sites, and castles, etc.

For each location there is a link to one of my blog posts, an external website, or one of my photo albums.

This map and all the links illustrate just how varied and beautiful this northeast region of England truly is.

Northumberland is one of the least populated counties in England. Most of the population is concentrated in the southeast of the county, in areas where there were, until the 1980s, thriving coal-mining communities, and a rich legacy of heavy industry along the Tyne, such as ship-building. The landscape has been reclaimed, spoil heaps have been removed, and nature restored over areas that were once industrial wastelands.

So why did we choose to make this move, almost 230 miles north from our home (of almost 40 years) in Worcestershire? After all, Worcestershire (and surrounding counties in the Midlands) is a beautiful county, and we raised our two daughters there, at least in their early years.

When we moved back to the UK in 1981 after more than eight years in South and Central America, we bought a house in Bromsgrove, a small market town in the north of the county, and very convenient for my daily 13-mile commute into The University of Birmingham, where I taught in the Department of Plant Biology. And there we happily stayed until mid-1991 when I accepted a position at the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in the Philippines, while keeping our house empty but furnished for the next 18 years.

Retiring in April 2010, we moved back to Bromsgrove, getting to know the town and surrounding counties again. Joining the National Trust in 2011 (and English Heritage a couple of years or so later) gave us an added incentive to explore just how much the Midlands had to offer: beautiful landscapes, historic houses and castles, and the like. You can view all the places we visited on this map.

But we had no family ties to Bromsgrove. And to cap it all, our elder daughter Hannah had studied, married, and settled in the United States and, as I mentioned before, Philippa was already in the northeast.

For several years, we resisted Philippa’s ‘encouragement’ to sell up and move north. After all we felt it would be a big and somewhat uncertain move, and (apart from Philippa and her family) we had no connections with the region. But in early January 2020, we took the plunge and put our house on the market, with the hope (expectation?) of a quick sale. Covid-19 put paid to that, but we finally left Bromsgrove on 30 September.

Last moments at No. 4.

We are now happily settled in North Tyneside and, weather permitting, we get out and about for day excursions as often as we can. There’s so much to discover.

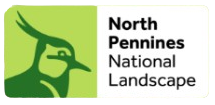

What we hadn’t done, until last week, was explore the hills southwest of Newcastle in the

What we hadn’t done, until last week, was explore the hills southwest of Newcastle in the

I was quite unaware of the waterfall’s existence until fairly recently, when I read a crime novel by Northumberland-born author

I was quite unaware of the waterfall’s existence until fairly recently, when I read a crime novel by Northumberland-born author