On 20 May 2015, a long article was published in The Guardian about the Svalbard Global Seed Vault (SGSV), popularly—and rather unfortunately—known as the ‘Doomsday Vault’. I’ve recently been guilty of using that moniker simply because that’s how the vault has come to be known, rightly or wrongly, in the media.

Authored by US-based environment correspondent of The Guardian, Suzanne Goldenberg, the article had the headline grabbing title: The doomsday vault: the seeds that could save a post-apocalyptic world.

You get a flavor of what’s in store, however, from the very first paragraph. Goldenberg writes: ‘One Tuesday last winter, in the town nearest to the North Pole, Robert Bjerke turned up for work at his regular hour and looked at the computer monitor on his desk to discover, or so it seemed for a few horrible moments, that the future of human civilisation was in jeopardy.’

Turns out there was a relatively minor glitch in one of the supplementary cooling systems of this seed repository under the Arctic permafrost where millions of seeds of the world’s most important food staples and other species are being stored, duplicating the germplasm conservation efforts of the genebanks from which they were sent. Hardly the stuff of Apocalypse Now. So while making a favorable case for the need to store seeds in a genebank like the Svalbard vault, Goldenberg ends her introduction with this somewhat controversial statement: ‘Seed banks are vulnerable to near-misses and mishaps. That was the whole point of locating a disaster-proof back-up vault at Svalbard. But what if there was a bigger glitch – one that could not be fixed by borrowing a part from the local shop? There is now a growing body of opinion that the world’s faith, in Svalbard and the Crop Trust’s broader mission to create seed banks, is misplaced. [The emphasis in bold is mine.] Those who have worked with farmers in the field, especially in developing countries, which contain by far the greatest variety of plants, say that diversity cannot be boxed up and saved in a single container—no matter how secure it may be. Crops are always changing, pests and diseases are always adapting, and global warming will bring additional challenges that remain as yet unforeseen. In a perfect world, the solution would be as diverse and dynamic as plant life itself.’

I have several concerns about the article—and the many comments it elicited that stem, unfortunately, from lack of understanding on the one hand and ignorance and prejudice on the other.

- Goldenberg gives the impression that it’s an either/or situation of ex situ conservation in a genebank versus in situ conservation in farmers’ fields or natural environments (in the case of crop wild relatives).

- There is a perception apparently held by some that the development of the SGSV has been detrimental to the cause of in situ conservation of crop wild relatives.

- Because there is no research or use of the germplasm stored in the SGSV, then it only has an ‘existence value’. Of course this does not take into account the research on and use of the same germplasm in the genebanks from which it was sent to Svalbard. Therefore Svalbard by its very nature is assumed to be very expensive.

- The role of Svalbard as a back-up to other genebank efforts is not emphasized sufficiently. As many genebanks do not have adequate access to long-term conservation facilities, the SGSV is an important support at no cost directly to those genebanks as far as I am aware. However, Svalbard can never be a panacea. If seeds of poor quality (i.e less than optimum viability) are stored in the vault then they will deteriorate faster than good seeds. As the saying goes: ‘Junk in, junk out’.

- The NGO perspective is interesting. It seems it’s hard for some of our NGO colleagues to accept that use of germplasm stored in genebanks actually does benefit farmers.Take for example the case of submergence tolerant rice, now being grown by farmers in Bangladesh and other countries on land where a consistent harvest was almost unheard of before. Or the cases where farmers have lost varieties due to natural disasters but have had them replaced because they were in a genebank. My own experience in the Cagayan valley in the northern Philippines highlights this very well after a major typhoon in the late 1990s devastated the rice agriculture of that area. See the section about on farm management of rice germplasm in this earlier post. They also still harbour a concern that seeds in genebanks are at the mercy of being expropriated by multinationals. In the comments, Monsanto was referred to many times, as was the issue of GMOs. I addressed this in the comment I contributed.

I added this comment that same day on The Guardian web site:

‘For a decade during the 1990s I managed one of the world’s largest and most important genebanks – the International Rice Genebank at the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in the Philippines. Large, because it holds over 116,000 samples of cultivated varieties and wild species of rice. And important, because rice is the most important food staple feeding half the world’s population several times daily.

The Svalbard Global Seed Vault (SGSV), the so-called ‘Doomsday Vault’ in Spitsbergen, holds on behalf of IRRI an almost complete duplicate set of samples (called ‘accessions’), in case something should happen to the genebank in Los Baños, south of Manila. I should add that for decades the USDA has also held a duplicate set in its genebank at Fort Collins in Colorado, under exactly the same ‘black box’ terms as the SGSV.

Germplasm is conserved so that it can be studied and used in plant breeding to enhance the productivity of the rice crop, to increase its resilience in the face of climate change, or to meet the challenge of new strains of diseases and pests. The application of molecular biology is unlocking the mysteries of this enormous genetic diversity, making it accessible for use in rice improvement much more efficiently than in past decades.

Many genebanks round the world and the collections they manage do not have access to long-term and safe storage facilities. This is where the SGSV plays an important role. Genebanks can be at risk from a whole range of natural threats (earthquakes, typhoons, volcanic eruptions, etc.) or man-made threats: conflicts, lack of resources, and inadequate management that can lead to fires, flooding, etc. Just take the example of the International Rice Genebank. The Philippines are subject to the natural threats mentioned, but the genebank was designed and built to withstand these. The example of the ICARDA genebank in Aleppo highlights the threat to these facilities from being located in a conflict zone.

To understand more about what it means to conserve a crop like rice please visit this post on my blog. There is an enlightening 15 minute video there that I made about the genebank.

It is not a question of taking any set of seeds and putting them into cold storage. Only ‘good’ seeds will survive for any length of time under sub-zero conditions. Many studies have shown that if stored at -18C, seeds with initial high viability may be stored for decades even hundreds of years. The seeds of many plant species – including most of the world’s most important food crops like rice, wheat, maize and many others conform to this pattern. What I can state unequivocally is that the seeds from the genebanks of the world’s most important genebanks, managed like that of IRRI under the auspices of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR), have been routinely tested for viability and only the best sent to Svalbard.

Prof. Phil Pardey, University of Minnesota

The other aspect of Goldenberg’s otherwise excellent article are the concerns raised by a number of individuals whose ‘comments’ are quoted. I count both Phil Pardey and Nigel Maxted among my good friends, and it seems to me that their comments have been taken completely out of context. I have never heard them express such views in such a blunt manner. Their perspectives on conservation and use, and in situ vs. ex situ are much more nuanced as anyone will see for themselves from reading their many publications. The SEARICE representative I do not know, but I’ve had many contacts with her organization. It’s never a question of genebank or ex situ conservation versus on-farm or in situ conservation. They are complementary and mutually supportive approaches. Crop varieties will die out for a variety of reasons. If they can be stored in a genebank so much the better (not all plant species can be stored successfully as seeds, as was mentioned in Goldenberg’s article). The objection to genebanks on the grounds of permitting multinationals to monopolize these important genetic resources is a red herring and completely without foundation.

So the purpose of the SGSV is one of not ‘putting all your eggs in one basket’. Unfortunately the name ‘Doomsday Vault’ as used by Goldenberg has come to imply a post cataclysm world. It’s really much more straightforward than that. The existence of the SGSV is part of humanity’s genetic insurance policy, risk mitigation, and business continuity plan for a wise and forward-thinking society.’

Over the next couple of days others chipped in with first hand knowledge of the SGSV or genetic conservation issues in general.

Simon Jeppson is someone who has first-hand knowledge and experience of the SGSV, and he wrote: ‘I’m currently working as the project coordinator of the Svalbard Global Seed Vault on behalf of NordGen and I just wanted to add some of my reflections on this article some of the comments.

is someone who has first-hand knowledge and experience of the SGSV, and he wrote: ‘I’m currently working as the project coordinator of the Svalbard Global Seed Vault on behalf of NordGen and I just wanted to add some of my reflections on this article some of the comments.

This article is an interesting read but a rather unbalanced one. The temperature increase that is described as putting the world heritage in jeopardy is a misconception. There has been a background study used as a worst case scenario during the planning stage of the Svalbard Global Seed Vault based on the seeds stored in the old abandoned mine shaft mentioned. These results were published in 2003 and even the most recent data (after 25 years in permafrost conditions prevailing in the same mountain without active cooling) shows that all samples are still viable. Anyone curious about this can for themselves try out various storage temperatures and find out the predicted storage time for specific crops at: http://data.kew.org/sid/viability/

Further I have some reflections regarding some of the recently posted comments. The statement “Most seed resources for plant breeding come from farmers’ fields via national seed stores in developing countries: these countries are not depositing in Svalbard.” is wrong; more than 60% of the deposited material originates from developing countries. Twenty-three of depositors represent national or regional institutes situated in developing counties, 12 are international centers and 28 are from developed countries according to IMF. This data is readily available at: http://www.nordgen.org/sgsv

Finally, a comment about the statement that “Seeds will not be distributed – only ever sent back to the institute that provided them. The reason is that seeds commonly have seed-borne diseases, sometimes nasty viruses and the rest.” This statement is also a misconception. The seeds samples stored in the vault are of the same seed lots already readily distributed worldwide from the depositing institutes. There are more than 1750 plant genetic institutes many of them distributing several thousand samples every year.’

Nigel Maxted is a senior lecturer in the School of Biosciences at the University of Birmingham. As I suspected, when I commented on Goldenberg’s article, Nigel’s contribution to the discussion was taken out of context. He commented: ‘I believe I have been mis-quoted in this article, I do think the Svalbard genebank is worthwhile and I hope the Trust reach their funding goal, even though ex situ does freeze evolution for the accessions included, it provides our best chance of long-term stability for preserving agrobiodiversity in an increasingly unstable world.

Nigel Maxted is a senior lecturer in the School of Biosciences at the University of Birmingham. As I suspected, when I commented on Goldenberg’s article, Nigel’s contribution to the discussion was taken out of context. He commented: ‘I believe I have been mis-quoted in this article, I do think the Svalbard genebank is worthwhile and I hope the Trust reach their funding goal, even though ex situ does freeze evolution for the accessions included, it provides our best chance of long-term stability for preserving agrobiodiversity in an increasingly unstable world.

I was trying to make a more nuanced point to Suzanne, that I strongly support complementary conservation that involves both in situ and ex situ actions. However at the moment if we compare the financial commitment to in situ and ex situ conservation of agrobiodiversity, globally over 99% of funding is spent on ex situ alone, therefore by any stretch of the imagination can we be considered to be implementing a complementary approach? I was used to make a point and I suppose it would be naive of me to complain, but I hope one day we will stop trying to create an artificial dichotomy between the two conservation strategies and wake up to the need for real complementary conservation. Conservation that includes a balanced range of in situ actions as well to conservation agrobiodiversity before it is too late for us all.’

Geoff Hawtin is someone who knows what he’s talking about. As Director General of the International Plant Genetic Resources Institute for just over a decade from 1991, and the founding Executive Secretary of the Global Crop Diversity Trust, Geoff had several telling comments: ‘As someone who has worked for the last 25 years to help conserve the genetic diversity of our food crops, I welcome the article by Suzanne Goldenberg in spite of its very many inaccuracies and misconceptions. She rightly draws attention to the plight of what is arguably the world’s most important resource in the fight against food and nutritional insecurity. If this article results in more attention and funds being devoted to safeguarding this resource—whether on farm or in genebanks—it will have served a useful purpose.

Geoff Hawtin is someone who knows what he’s talking about. As Director General of the International Plant Genetic Resources Institute for just over a decade from 1991, and the founding Executive Secretary of the Global Crop Diversity Trust, Geoff had several telling comments: ‘As someone who has worked for the last 25 years to help conserve the genetic diversity of our food crops, I welcome the article by Suzanne Goldenberg in spite of its very many inaccuracies and misconceptions. She rightly draws attention to the plight of what is arguably the world’s most important resource in the fight against food and nutritional insecurity. If this article results in more attention and funds being devoted to safeguarding this resource—whether on farm or in genebanks—it will have served a useful purpose.

The dichotomy between in situ and ex situ conservation is a false one. The two are entirely complementary and both approaches are vital. For farmers around the world the genetic diversity of their landraces and local varieties is their lifeblood—a living resource that they can use and mould to help meet their current and future needs and those of their families.

But we all live in a world of rapid and momentous change and a world in which we all depend for our food on crops that may have originated continents away. The diversity an African farmer—or plant breeder—needs to improve her maize or beans may well be found in those regions where these crops were originally domesticated – in this case in Latin America, where to this day genetic diversity of these two crops remains greatest. Without the work of genebanks in gathering and maintaining vast collections of such genetic diversity, how can such farmers and breeders hope to have access to the traits they need to develop new crop varieties that can resist or tolerate new diseases and pests, or that can produce higher yields of more nutritious food, or that are able to meet the ever growing threats of heat, drought and flooding posed by climate change?

Scientists have been collecting genetic diversity since at least the 1930s, but efforts expanded significantly in the 1970s and 80s in response to growing recognition that diversity was rapidly disappearing from farmers fields in many parts of the world as a result of major shifts in agricultural production systems and the introduction and adoption of new, higher yielding varieties. Today, thanks to these pioneering efforts, diversity is being conserved in genebanks that no longer exists in the wild or on farmers’ fields.

The common misconception that the Svalbard Global Seed Vault exists to save the world following an apocalyptic disaster is perpetuated, even in the title of the article. In reality, the SGSV is intended to provide a safety-net as a back-up for the world’s more than 1,700 genebanks which themselves, as pointed out in the article, are often far from secure. At a cost of about £6 million to build and annual running and maintenance costs of less than £200,000 surely this ranks as the world’s most inexpensive yet arguably most valuable insurance policy.’

Finally, among the genetic resources experts, Susan Bragdon made the following comments: ‘I think the author overstates the fierce debates between the proponents of ex situ and in situ conservation. Most would agree that both are needed with in situ being complemented by ex situ.

Finally, among the genetic resources experts, Susan Bragdon made the following comments: ‘I think the author overstates the fierce debates between the proponents of ex situ and in situ conservation. Most would agree that both are needed with in situ being complemented by ex situ.

The controversy over money is because funders are not understanding this need for both and may feel they have checked off that box by funding Svalbard (which is perhaps better seen as an insurance policy—one never hopes to have to use one’s insurance policy.) Svalbard is of course sexier than the on-farm development and conservation of diversity by small scale farmers around the world. Donors can jet in, go dog sledding, see polar bears. Not as sexy to visit most small-scale farms but there are more and more exceptions (e.g., the Potato Park in Peru)

Articles like this set up a false choice between ex situ and in situ which is simply not shared except by a few loud voices. We need to work together to create the kind of incentives that make small scale farming in agrobiodiverse settings an attractive life choice.’

In her staff biography on the Quaker United Nations Office web page, it relates that ‘from 1997-2005 Susan worked with the International Plant Genetic Resources Institute as a Senior Scientist, Law & Policy, on legal and policy issues related to plant genetic resources and in particular managed projects on intellectual property rights, Farmers’ Rights, biotechnology and biological diversity, and on developing decision-making tools for the development of policy and law to manage plant genetic resources in the interest of food security.’

Comments are now closed on The Guardian website for this article. I thought it would useful to bring together some of the expert perspectives in the hope of balancing the arguments—since so many readers had taken the ‘apocalypse’ theme at face value— and making them more widely available.

When I have time, I’ll address some of the perspectives about genebank standards.

My flight from Manila arrived quite late at night, and a vehicle and driver were sent to KL airport to pick me up. On the journey from the airport my driver became quite chatty. He asked where I was from, and when I told him I was working in the Philippines on rice, he replied ‘You must be working at IRRI, then‘ (

My flight from Manila arrived quite late at night, and a vehicle and driver were sent to KL airport to pick me up. On the journey from the airport my driver became quite chatty. He asked where I was from, and when I told him I was working in the Philippines on rice, he replied ‘You must be working at IRRI, then‘ (

I was visiting in connection with the

I was visiting in connection with the

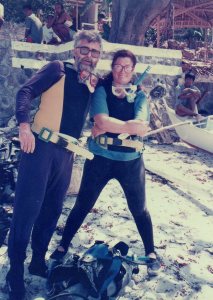

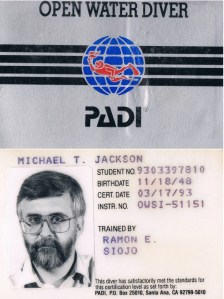

In fact, when we did go to the beach in Puerto Galera for the first time, in February 1992 (just a few weeks after Steph, Hannah and Philippa had joined me from the UK), I’d never even snorkeled before! So the last thing on my mind was the idea of taking a scuba diving course. Snorkeling was fine – once I’d got the hang of it, and learned to relax and actually breathe with my face in the water. So we invested in masks, boots and fins, and started visiting Anilao about once a month. Our first resort was

In fact, when we did go to the beach in Puerto Galera for the first time, in February 1992 (just a few weeks after Steph, Hannah and Philippa had joined me from the UK), I’d never even snorkeled before! So the last thing on my mind was the idea of taking a scuba diving course. Snorkeling was fine – once I’d got the hang of it, and learned to relax and actually breathe with my face in the water. So we invested in masks, boots and fins, and started visiting Anilao about once a month. Our first resort was

The volcanoes are spectacular, and my potato work took me almost every week to the slopes of the Irazú volcano, the main potato growing area of the country, and about 50 km from Turrialba. It dominates the horizon from San Jose, and its most famous recent activity was in 1963 on the day that President Kennedy landed in San José for a state visit. That eruption lasted for more than a year. But the volcanic activity is the basis of deep and rich soils on the slopes of the volcano.

The volcanoes are spectacular, and my potato work took me almost every week to the slopes of the Irazú volcano, the main potato growing area of the country, and about 50 km from Turrialba. It dominates the horizon from San Jose, and its most famous recent activity was in 1963 on the day that President Kennedy landed in San José for a state visit. That eruption lasted for more than a year. But the volcanic activity is the basis of deep and rich soils on the slopes of the volcano. Costa Rica has had an interesting history. After a short civil war in 1948 the armed forces were abolished, and the country invested heavily in social programs and education. It also established a nation-wide network of national parks, and has one of the biggest proportions of land dedicated to national parks of any country. In April 1980 Steph, Hannah and me were staying at the

Costa Rica has had an interesting history. After a short civil war in 1948 the armed forces were abolished, and the country invested heavily in social programs and education. It also established a nation-wide network of national parks, and has one of the biggest proportions of land dedicated to national parks of any country. In April 1980 Steph, Hannah and me were staying at the

I never imagined for one minute when I moved to the Philippines in 1991 that I’d ever take up scuba diving. I’ve never been one for water sports, or lazing about on the beach either. But that changed not long after Steph, Hannah and Philippa arrived in the Philippines, and we decided to see what the beach had to offer. This is how it happened.

I never imagined for one minute when I moved to the Philippines in 1991 that I’d ever take up scuba diving. I’ve never been one for water sports, or lazing about on the beach either. But that changed not long after Steph, Hannah and Philippa arrived in the Philippines, and we decided to see what the beach had to offer. This is how it happened. Sadly, Arthur died in September 2002, but Lita has kept the business going – and has expanded it significantly in terms of rooms and other facilities. And of course the resort is a haven for divers who come from all over the world, although most are actually based in the Philippines. It rapidly became a focal point for IRRI staff wanting a weekend away at the beach.

Sadly, Arthur died in September 2002, but Lita has kept the business going – and has expanded it significantly in terms of rooms and other facilities. And of course the resort is a haven for divers who come from all over the world, although most are actually based in the Philippines. It rapidly became a focal point for IRRI staff wanting a weekend away at the beach.