Over recent weeks, Steph and I have been enjoying the latest series of Digging for Britain on BBC2, hosted by Alice Roberts who is Professor of Public Engagement in Science at the University of Birmingham. In this ninth series (as in the earlier programs) she visited digs all over the UK where archaeologists were busy uncovering our distant (and not-so-distant) past, and the lives of the people who lived there.

Over recent weeks, Steph and I have been enjoying the latest series of Digging for Britain on BBC2, hosted by Alice Roberts who is Professor of Public Engagement in Science at the University of Birmingham. In this ninth series (as in the earlier programs) she visited digs all over the UK where archaeologists were busy uncovering our distant (and not-so-distant) past, and the lives of the people who lived there.

In one program she visited a (secret) site in Rutland (England’s smallest county in the East Midlands) where, in a farmer’s field, the most remarkable Roman mosaic floor had been uncovered, depicting scenes from the Trojan War. This was only one of many treasures that were ‘discovered’ during the series.

The British landscape has been transformed by multiple waves of immigration and conquest over thousands of years. But scrape away the surface, as archaeologists are wont to do, and fascinating histories begin to emerge, from prehistoric times through to the arrival of the Romans in AD 43, and in the centuries afterwards.

Sites like Stonehenge or the Avebury Stone Circle remind us that humans were living in and modifying these landscapes thousands of years before the Romans arrived on these shores.

Avebury Stone Circle.

Northumberland in the northeast of England (where I now live) is particularly rich in Roman remains. Besides the iconic Hadrian’s Wall, forts like Housesteads or Chew Green, and towns like Corbridge and Vindolanda are a visible reminder that these islands were once under the military control of an empire the like of which the world had never seen before. Northumberland was the northwest frontier.

And after the Romans departed in the 5th century AD, northern tribes such as by Angles, Saxons, and Jutes from continental Europe made these islands their home.

However, I often view our landscape as essentially post-Norman (that is, after 1066) since the Normans (and their descendants) left so many statements of their hegemony: magnificent castles (such as Prudhoe, Warkworth, and Dunstanburgh that stand as proud ruins even today), manor houses, churches and abbeys, and royal hunting parks.

I guess our appetite for the archaeological past was whetted when we moved to Peru in 1973. Within two weeks of landing in Lima in January I had already visited Machu Picchu while attending a meeting in Cuzco. Then, after Steph arrived in Lima in July, we spent many weekends exploring the coast and heading off into the numerous valleys that lead inland from Lima. In December, I took her to Machu Picchu (for a delayed honeymoon!)

Over the three years we spent in Peru, five in Central America, and more recently in the southwestern United States, we have visited a number of iconic pre-Columbian archaeological sites, and others less well known.

It’s not just the remains that various cultures have left behind, however. It’s also understanding their connection with the environment, the types of agriculture practiced for example, and the crops that were domesticated and brought into cultivation (a particular interest of mine).

So permit me to take you on a brief archaeological travelogue through the Americas.

Hiram Bingham III

As I’ve already mentioned Machu Picchu, perhaps I should start there. I guess it’s not only the location of this Incan refuge, but something of the mystery that surrounds it until it was ‘discovered’ by Hiram Bingham III in 1911 (although there are earlier claimants).

But tales of a lost city in Peru certainly caught the public imagination, and soon Machu Picchu was a notable tourist destination. In 1973, the rail journey between Cuzco and Machu Picchu was slow and left early in the morning. Nowadays the line has been upgraded and beside the river (way below the ruins) a small town has sprung up to accommodate the multitude of tourists who descend on Machu Picchu daily from all over the world.

I made just a day visit there in January 1973. However, Steph and I were lucky to reserve a room at the turista hotel that once stood just outside the ruins. So, once most tourists had returned to Cuzco late in the afternoon, we (and a handful of other hotel guests) had the ruins to ourselves. Next morning we breakfasted early to watch the sun rise, and enjoy the peace and quiet of this iconic site until, late morning, it was thronging once again with a trainload of tourists.

In many ways it’s not surprising that Machu Picchu remained ‘undiscovered’ for so long, five centuries after the last Inca took refuge there. Other ruins, further out into the jungle, have been uncovered in recent years, like Choquequirao, a two day hike from Cuzco.

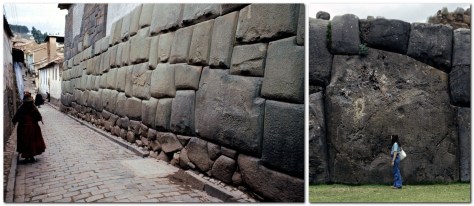

What is remarkable about Cuzco, the Inca capital before the Spaniards arrived in the 16th century, is the juxtaposition of Incan and colonial architecture, in many places the latter built over the former. The beautiful Incan stonework is epitomized, for example, in the 12-sided stone in Calle Jatun Rumiyoc, east of the Plaza de Armas (the city’s main square).

Or the foundations of the Qorikancha temple (right) on which the colonizing Spaniards built the Santo Domingo convent five centuries ago.

Or the foundations of the Qorikancha temple (right) on which the colonizing Spaniards built the Santo Domingo convent five centuries ago.

Outside and overlooking Cuzco from the north is the impressive Inca fortress Sacsayhuamán (below). It’s not only its size, but especially the precision with which the stones have been placed together, some stones (like that shown below) weighing tens of tons at the very least.

Just 32 km to the northeast of Cuzco, and standing at the head of the Sacred Valley of the Incas is the market town of Pisac. Even in 1973 it was a major tourist attraction, even though it had changed little from almost 40 years previously when my PhD supervisor Professor Jack Hawkes had visited as a young man of 24. Check out these photos I took in 1973, and compare them with scenes in the film that Jack made in 1939 (after minute 25:25).

Above the town, 15th century terraces or andenes stretch up the hillside, where there are also temple remains; due to limited time we didn’t have an opportunity of exploring those nor travel further down the valley to Ollantaytambo where there are also impressive Inca remains.

Andenes above the town of Pisac.

But what is particularly remarkable about the Incas is the relative short period (perhaps a little over 300 years until the Spanish conquest in the mid-16th century) in which they held domain over many of the other cultures that had gone before them. Not only in the mountains, but on the coast as well, as I shall describe a little later.

But talking of terraces, I was fortunate to visit the small town of Cuyo Cuyo in Puno in the far south of Peru, in February 1974 while undertaking some fieldwork for my PhD research. Agricultural terraces built centuries ago are still being farmed communally today (at least when I visited almost 50 years ago).

Potato terraces at Cuyo Cuyo, Puno in southern Peru.

While some terraces had fallen into disrepair, the majority were still being carefully tended, and planted with a rotation of potatoes-oca (a minor Andean tuber crop)-barley or beans-fallow over about an eight year period. Impressive as they are, terraces like those at Cuyo Cuyo can be seen in many valleys all over Peru, but perhaps not so actively farmed as there.

Puno is one of the highest cities in the world, at just over 3800 m (12,556 ft), alongside Lake Titicaca, the highest navigable lake.

On a peninsula overlooking a lake about 33 km northwest of Puno stands a cluster of rather peculiar round towers, known as chullpas, of the most exquisite masonry, mostly ruined. Some of these stand 12 m tall. This is Sillustani, a pre-Incan Aymara cemetery site.

It seems that once this area came under Inca control, many of the chullpas were redressed with Incan masonry, much of what we see today.

One could be forgiven for imagining that the coastal desert of Peru is one huge cemetery, such is the extent of the burial sites where Moche (AD 100 -AD 800) and Chimú civilizations (AD 900 until about AD 1470 when the Incas arrived on the scene), and others, held sway leaving behind a vast array of artefacts that tell us so much about them. Having no written language, their pottery tells us much about the crops they grew, the animals they kept, even their sex lives.

Mummy bundles have been excavated in their thousands, and many of the contents are now carefully stored in one of Lima’s most prestigious museums, with just a fraction on display at any one time. Take a moment to read about the museum and its contents that I published in 2017.

All along the coast there are temples built of mud bricks, like the one below. I don’t remember exactly where this was located, but I think maybe in one of the valleys inland from the coast, 4-500 km north of Lima.

One of the more important ones lies just 40 km (or 25 miles) south of Lima. Pachacamac covers about 240 hectares, and was continuously occupied from about AD 100 until the Spanish conquest, 1300 years later.

North of Lima there are two interesting sites.

Just outside the coastal city of Casma (about 350 km or 165 miles north of Lima) stand the unusual remains of Cerro Sechín, an archaeological complex covering many hectares, and one of the oldest sites in Peru, dating back about 4000 years. The striking elements of this site are the bas-reliefs etched into the stonework depicting war-like scenes, of warriors, mutilation and the like. It really is a most unusual site. Steph and I visited there (with our CIP friends John and Marian Vessey) in 1974.

At Sechín, as at other coastal sites, the archaeological evidence shows that not only did the inhabitants practice agriculture (maize and beans being the domesticated staples) but depended on the abundant marine resources close by.

Further north, outside the city of Trujillo stand the degraded remains of Chan Chan, once the great Chimú capital covering 20 km², and built of adobe bricks. It’s regarded as the largest adobe-built city in the world. The complex comprises plazas and citadels, and because of the extremely arid conditions, many of the walls (and their carvings of animals, birds and marine life) have survived to the present.

While the coastal desert is one of the driest in the world, it does rain heavily from time-to-time, and when we visited the walls were being protected from further rain erosion.

Unfortunately, I never got to view the world-famous Nazca Lines from the air. As you cross the Nazca plain (over 400 km south of Lima) you can see some of the lines stretching into the distance but with no comprehension of what they might represent. Furthermore, indiscriminate vehicular access to this area in the past (even army manoeuvres!) has left indelible tracks across the desert, desecrating some of the incredible figures there.

The Nazca Plain from the Panamericana Sur. You can see vehicle tracks heading off into the desert.

The monkey on the Nazca lines.

On the southeastern side of the Cordillera Blanca in the Department of Ancash the ruins at Chavín de Huántar, a site that was occupied over 3000 years ago, and regarded as the oldest highland culture in Peru.

‘El Castillo’ at Chavín de Huántar.

A stone head or tenon at Chavín de Huántar.

I visited there in May 1973 when collecting potatoes in that part of Peru, and again with Steph and the Vesseys a year later.

Just outside the highland city of Cajamarca (2750 m, about 180 km inland from the coast between Trujillo and Chiclayo) are the Ventanillas de Otuzco, and ancient necropolis (over 2000 years old) carved in the rock face.

Steph and I lived in Costa Rica in Central America for almost five years from April 1976. There are few remains of indigenous cultures around the country (unlike Guatemala or Mexico for instance).

However, just under 20 km north of Turrialba (where we lived) lie the enigmatic remains of Guayabo National Monument, which I wrote about in October 2017.

There’s good evidence however that this site was first occupied over 2000 years ago, until the beginning of 15th century.

In the jungle of northeast Guatemala stands the ruins of ancient Tikal, a Mayan complex dating back more than 2400 years, surely one of the most iconic archaeological sites on the planet (and which even featured in the very first Star Wars movie).

Steph and I flew there in 1977, on an Aviateca DC3, spending one night in one of the lodges. Back in the day it was possible to reach Tikal only by air, but the whole region has now opened up via roads and even an international airport in the nearby city of Flores, just 64 km to the south. I guess the site must now be overrun to some extent by tourists, much like has happened at Machu Picchu. We were fortunate to visit here, as with many of the sites I have described, before they appeared on the everyday tourist routes.

We spent hours wandering around this huge site, and managing to see just a fraction probably. It’s hard to imagine just how steep the temple steps are. No wonder Steph was out of breath. We later learned that she was pregnant when we were there.

It seems that Tikal was conquered, around the 4th century AD, from Teotihuacán from the valley of Mexico. And it’s there, north of present day Mexico City that the important temple complex of Teotihuacán can be found. Its famous Temple of the Sun and others are significant Mesoamerican pyramids standing on a site that covers 21 km². We visited there in April 1975 on our way back to the UK, staying with our friends John and Marian Vessey who had left CIP to join a sister research center, the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) that is located not far from Teotihuacán. I’ve been back there a couple of times in the 1990s and 2000s.

Our elder daughter Hannah moved to Minnesota in 1998 to complete her undergraduate degree at Macalester College in St Paul, then registered at the University of Minnesota for her PhD in psychology. In 2006 she married Michael, and they set up home in St Paul. Grandchildren Callum and Zoë came along in 2010 and 2012, respectively. And since I retired from IRRI in 2010 and returned to the UK, Steph and I have visited them every year, and made some pretty impressive road trips across many parts of the USA. That is until Covid 19 put paid to international travel for the time being.

In 2011, we had the opportunity of fulfilling a lifetime ambition: to travel to the Grand Canyon in Arizona. So we flew from Minneapolis-St Paul (MSP) to Phoenix (PHX) to take in the Grand Canyon, and travel extensively through Arizona and New Mexico. We visited three sites on this trip, but only one, the Canyon de Chelly, was a pre-trip destination. We fortunately came across the other two during the course of our travels.

We stopped in Flagstaff on our first night, having traveled north from Phoenix through the Sedona valley and having our first taste of the magnificent red-rock buttes. Then, the following day as we headed north on US89, we saw a sign to Sunset Crater Volcano National Monument.

Checking the map, I saw that we could make a useful diversion, and also taking in further north Wupatki National Monument, a 100-room pueblo and other buildings in the surrounding small ‘canyons’. It is believed that peoples first gathered here around 1100 AD, just a century after the Sunset Crater Volcano erupted. Even today, Wupatki is revered by the Hopi, Zuni, and Navajo tribes.

After a couple of nights at the Grand Canyon (South Rim), and a detour to Monument Valley we found ourselves in Chinle, in northeast Arizona.

In the heart of the Navajo Nation, Chinle is the gateway to the Canyon de Chelly National Monument. Occupied for thousands of years, Canyon de Chelly is a very special place, and somewhere in the USA that I would return to tomorrow, given half the chance.

It was settled by ancient Puebloans at least 4000 years ago, finding the steep-sided canyon an ideal place to settle, raise their families in a safe environment, and raise their crops. These included, after the Spanish arrival in the Americas in the 16th century, peaches that were destroyed during reprisal raids by the US Army in the late 19th century, led by Indian agent and Army officer Kit Carson. In fact, it was reading a biography of Kit Carson in February 2011 that was the impetus to visit Canyon de Chelly.

We viewed the canyon from the rim only. Access to the canyon floor is limited to just one access point to visitors on foot, who can climb the long way down (800-1000 feet) to view houses built into the cliff face. We could see that from the rim, as well as two others at different locations and at different heights on the canyon wall. The Navajo must have felt they were safe from invaders, but unfortunately not, making a last stand at the tall pillar Spider Rock that you can see in one of the images below.

The Navajo do provide guided tours into the canyon, and if I ever return, I’ll spend several days there and take the tour.

On the penultimate day of our road trip, passing through Los Alamos (where the first atom bombs were designed) in New Mexico, we’d seen signposts to Bandelier National Monument. There’s good evidence of human settlement in this area over 10,000 years ago; ancestral Puebloan peoples settled here 2000 years ago, but had moved on by the mid-16th century.

Rooms were carved into the soft rock or tuff, with ladders used to scale the cliff face. In a few places rock art can be seen. There is also good evidence of agriculture based on the staple triumvirate of maize, beans, and squashes, as well as hunting for deer. Since we had to make progress towards Albuquerque for the last night before flying back to MSP, we were not able to spend as much time exploring the site as we wanted.

Nevertheless, with our visits to Wupatki, Canyon de Chelly, and Bandelier, we gained an appreciation of ancient lives in these desert environments. Of course there’s more to see and learn about the Chaco culture that thrived in New Mexico. Ancient settlements are scattered all over Arizona, New Mexico, and Colorado.