and the CGIAR

and the CGIAR

The International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), based in Los Baños, Philippines (about 65 km south of Manila), was founded in 1960, the first of what would become a consortium of 15 international agricultural research institutes funded through the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR).

Listen to CGIAR pioneers Dr Norman Borlaug and former World Bank President (and US Defense Secretary) Robert McNamara talk about how the CGIAR came into being in 1971.

I spent almost 19 years at IRRI, more than eight years at a sister center in Peru, the International Potato Center (CIP), and worked closely with another, Bioversity International (formerly known as the International Board for Plant Genetic Resources – IBPGR – from its foundation in 1974 to October 1991, when it became the International Plant Genetic Resources Institute – IPGRI – until 2006).

Who funds IRRI and the other centers of the CGIAR?

IRRI and the other centers receive much of their financial support as donations from governments through their overseas development assistance budgets. In the case of the United Kingdom, the Department for International Development (DFID)is the agency responsible for supporting the CGIAR, it’s USAID in the USA, and the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) in Switzerland, for example. In the last decade, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation has become a major donor to the CGIAR.

During my second career at IRRI, from May 2001 until my retirement at the end of April 2010 I was responsible, as Director for Program Planning and Communications (DPPC), for managing the institute’s research portfolio, liaising with the donor community, and making sure, among other things, that the donors were kept abreast of research developments at IRRI. I had the opportunity to visit many of the donors in their offices in the capitals of several European countries and elsewhere. However, very few of the people responsible for the CGIAR funding in the donor agencies had actually visited IRRI (or, if they had, it wasn’t in recent years). One thing that did concern me in working with some donors was their blinkered perspectives on what constituted research for development, and the day-to-day challenges that an international institute like IRRI and its staff face. I guess that’s not surprising really since some had never worked outside their home countries let alone undertake field research.

International Centers Week 2002

In those days, the CGIAR used to hold its annual meeting – International Centers Week – in October, and for many years this was always held at the World Bank in Washington, DC. But from about 2000 or 2001, it was decided to move this annual ‘shindig’ outside the Bank to one of the countries where a center was located. In October 2002, Centers Week came to Manila in the Philippines, hosted by the Department of Agriculture.

What an opportunity, one that IRRI was not going to ignore, to have many of the institute’s donors visit IRRI and see for themselves what this great institution was all about. Having seen the initial program that would bring several hundred delegates to Los Baños over two days – on the 28th (visiting Philippine institutions) and 29th October (at IRRI) but returning to Manila overnight in between – we decided to invite as many donors as wished to be our guests overnight. Rumour had it that the Chair of the CGIAR then, Ian Johnson (a Vice President of the World Bank) and CGIAR Director Dr Franscisco Reifschneider, were not best pleased about this IRRI ‘initiative’.

Most donors did accept our invitation, and we hosted a dinner reception on the Monday evening, returning some of the hospitality we’d been offered during our visits to donor agencies. This also gave our scientists a great chance to meet with the donors and talk about their science. Most (but not all scientists) are the best ambassadors for their research and the institute; however, some just can’t avoid using technical jargon or see past the minutiae of their scientific endeavors.

As the dinner drew to a close, I spread word that the party would continue at my house, just a short distance from IRRI’s Guesthouse. As far as I remember about a dozen or so donor friends followed me down the hill, and we continued our ‘discussions’ into the small hours. Just after dawn I staggered out of bed and, with a rather ‘thick head’, went to see the ‘damage’ in our living room, where I found a large number of empty glasses, and several empty whisky, gin and wine bottles. A good time was had by all! Unfortunately it was also pouring with rain, which did nothing to lift my spirits. Our program for the day had been developed around a series of field visits – we didn’t have an indoor Plan B in case of inclement weather.

However, I’m getting ahead of myself. Let me tell you how did we went about organizing the IRRI Day on the 29th October.

Getting organized

Ron Cantrell, IRRI’s Director General in 2002 asked me to organize IRRI Day. But what to organize and who to involve? We decided very early on that, as much as possible, to show our visitors rice growing in the field, but with some laboratory stops where appropriate or indeed feasible, taking into account the logistics of moving a large number of people through relatively confined spaces.

Ron Cantrell, IRRI’s Director General in 2002 asked me to organize IRRI Day. But what to organize and who to involve? We decided very early on that, as much as possible, to show our visitors rice growing in the field, but with some laboratory stops where appropriate or indeed feasible, taking into account the logistics of moving a large number of people through relatively confined spaces.

How to move everyone around the fields without having the inconvenience getting on and off buses? In 1998 I had attended a symposium to mark the inauguration of the Dale Bumpers National Rice Research Center in Stuttgart, Arkansas (self-proclaimed Rice and Duck Capital of the World). To visit the various field plots we were taken around on flat-bed trailers, towed by a tractor. We sat on straw bails, and each trailer also had an audio system. It was easy to hop on and off at each of the stops along the tour. However, we had nothing of that kind at IRRI and, in any case, we reckoned that any trailers would need some protection against the sun – or worse, a sudden downpour.

And that’s how I began a serious collaboration with our Experimental Farm manager, Joe Rickman to solve the transport issue.

Joe Rickman

We designed and had constructed at least 10 trailers, or bleachers as they became known. As far as I know these are still used to take visitors around the experimental plots when appropriate.

So, transport solved. But what program of field and laboratory visits would best illustrate the work of the institute? In front of the main entrance to IRRI are many demonstration plots with roads running between them where we could show research on water management, long-term soil management, rice breeding, and pest management. We also opened the genetic transformation and molecular biology labs and, I think, the grain quality lab. I just can’t remember if the genebank was included. The genebank is usually on the itinerary for almost all visitors to IRRI but, given the numbers expected on IRRI Day, and that the labs are environment controlled – coll and low humidity – I expect we decided to by-pass that.

The IRRI All Stars

From the outset I decided that we would need staff to act as guides and hosts, riding the trailers, providing a running commentary between ‘research stations’. I put word out among the local staff that I was looking to recruit about 20-30 staff to act as tour guides; I also approached several staff who I knew quite well and who I thought would enjoy the opportunity of taking part. What amazed me is that several non-research staff approached me asking if they could participate, and once we’d made the final selection, we had both human resources and finance staff among the IRRI All Stars.

The IRRI All Stars L-R: Carlos Casal, Jr., Josefina Narciso, Ato Reano, Reycel Maghirang-Rodriguez, Arnold Manza, Crisel Ramos, Varoy Pamplona, Lina Torrizo, Tina Cassanova, Jessica Rey, Caloy Huelma, Beng Enriquez, Joe Roxas, Remy Labuguen, Sylvia Avance, Ailene Garcia-Sotelo, Mark Nas, Ofie Namuco, Estella Pasuquin, Ria Tenorio, Ninay Herradura, Lily Molina, Tom Clemeno, Joel Janiya.

Once we had a trailer available, then we began planning and practising in earnest. I wanted my colleagues to feel confident in their roles, knowledgeable about what everyone would see in the field, as well as feeling comfortable fielding any questions thrown at them by the visitors.

I think some of the All Stars felt it was a bit of a baptism by fire. I was quite tough on them, and encouraged everyone to critique each other’s ‘performance’. And things got tougher once we had the research scientists in the field strutting their stuff during the practice runs. My guides were merciless in their comments to colleagues about their research explanations. Not only did we reduce the jargon to a manageable level, but soon everyone appreciated that they had to be able to explain not only what they were researching, but why it was important to rice farmers. And in doing so, to actually talk to their audience, making eye contact and engaging with them.

It was worth all the time and effort we spent before IRRI Day. Because on the day itself, everyone shone. I don’t think I’ve been prouder of my colleagues. After the early morning rain, the clouds parted and by 9 am when we started the tours, it was a glorious Los Baños day at IRRI. The feedback from the delegates, especially the donor representatives, was overwhelming. Many had, as I mentioned earlier, a blinkered view of research for development, and rice research in particular. More than a few had a ‘Damascene experience’. Many had never even seen a rice paddy before. I believe that IRRI’s stock rose among the donor community during the 2002 International Centers Week – due in no small part to their very positive interactions with IRRI’s research staff and the All Stars.

On reflection, we had a lot of fun at the same time. It was extremely rewarding to see how positive all the staff were about contributing to the success of IRRI Day. But that’s the IRRI staff for you. Many a visitor has mentioned as they leave what a great asset are the staff to IRRI’s success. I know from my own 19 years there. In fact we had so much fun that just over a week later we held another IRRI Day for all staff, following the same route around the field and listening to the same researchers.

Using camera-mounted drones, it’s now possible to give IRRI’s visitors a whole new perspective.

Sponsored by the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), the 4th International Rice Congress brought together rice researchers from all over the world. Previous congresses had been held in Japan, India and last time, in 2010, in Hanoi, Vietnam (for which I also organized the science conference). This fourth congress, known as IRC2014 for short, had three main components:

Sponsored by the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), the 4th International Rice Congress brought together rice researchers from all over the world. Previous congresses had been held in Japan, India and last time, in 2010, in Hanoi, Vietnam (for which I also organized the science conference). This fourth congress, known as IRC2014 for short, had three main components:

Way back at the beginning of 2013 IRRI management asked me if I would like to organize the science conference in Bangkok, having taken on that role in 2009 before I retired from IRRI and for six months after I left. From May 2013 until IRC2014 was underway, I made four trips to the Far East, twice to Bangkok and three times to IRRI. We formed a

Way back at the beginning of 2013 IRRI management asked me if I would like to organize the science conference in Bangkok, having taken on that role in 2009 before I retired from IRRI and for six months after I left. From May 2013 until IRC2014 was underway, I made four trips to the Far East, twice to Bangkok and three times to IRRI. We formed a

Hailed by some as the new

Hailed by some as the new  When I started this blog some 20 months ago, I decided that I would write about topics related to the things I’ve done and seen throughout my professional life on three continents, as well as other topics that come to mind now that I’m retired and look back on the decades.

When I started this blog some 20 months ago, I decided that I would write about topics related to the things I’ve done and seen throughout my professional life on three continents, as well as other topics that come to mind now that I’m retired and look back on the decades. That was the mantra of one of my former IRRI colleagues, plant pathologist Tom Mew: Do the right science, and do the science right.

That was the mantra of one of my former IRRI colleagues, plant pathologist Tom Mew: Do the right science, and do the science right.

Let me state, right away, that I do not support the indiscriminate killing of animals. But we do have a crisis in agriculture here in the UK caused by the ongoing incidence and spread of bovine tuberculosis among cattle. And it’s particularly prevalent in the southwest. It seems the jury is out concerning the role of badgers in spreading the disease to cattle, and maintaining a reservoir of the pathogen to re-infect both disease-free badger populations and cattle herds. It’s costing the livestock industry – and us, the taxpayers – millions in compensation, never mind the heartache suffered by farmers as they watch their prize pedigree herds being taken away for slaughter. What about a vaccine you may ask? Under EU rules the use of a vaccine – even if an effective one was available (which experts admit may take up to 10 years more) – is not permitted. So what is needed are measures that reduce the level of environmental inoculum. And that means reducing the badger population or reducing the level of infection in badger populations. Badgers can be vaccinated against bovine TB, if they can be trapped, but vaccination will not cure sick animals and, according to information I have read, there are many very sick badgers wandering about the British countryside.

Let me state, right away, that I do not support the indiscriminate killing of animals. But we do have a crisis in agriculture here in the UK caused by the ongoing incidence and spread of bovine tuberculosis among cattle. And it’s particularly prevalent in the southwest. It seems the jury is out concerning the role of badgers in spreading the disease to cattle, and maintaining a reservoir of the pathogen to re-infect both disease-free badger populations and cattle herds. It’s costing the livestock industry – and us, the taxpayers – millions in compensation, never mind the heartache suffered by farmers as they watch their prize pedigree herds being taken away for slaughter. What about a vaccine you may ask? Under EU rules the use of a vaccine – even if an effective one was available (which experts admit may take up to 10 years more) – is not permitted. So what is needed are measures that reduce the level of environmental inoculum. And that means reducing the badger population or reducing the level of infection in badger populations. Badgers can be vaccinated against bovine TB, if they can be trapped, but vaccination will not cure sick animals and, according to information I have read, there are many very sick badgers wandering about the British countryside.

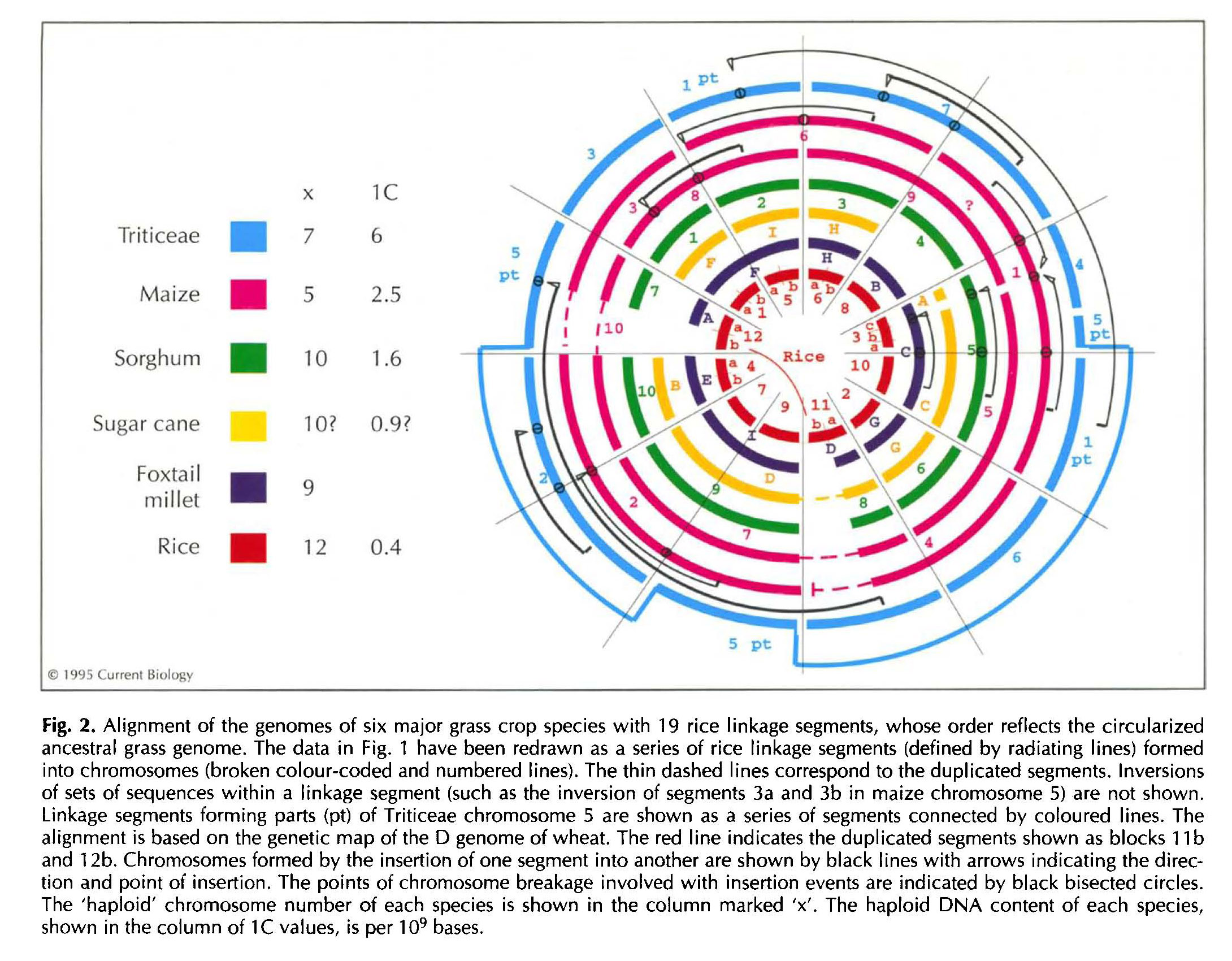

My former colleague, Bob Zeigler, Director General of the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in the Philippines, has often spoken of the ‘three revolutions’ that have dramatically transformed the way we develop new crops to feed a hungry world.

My former colleague, Bob Zeigler, Director General of the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in the Philippines, has often spoken of the ‘three revolutions’ that have dramatically transformed the way we develop new crops to feed a hungry world. It’s 60 years since the structure of DNA was elucidated by Watson and Crick, for which they and Maurice Wilkins were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1962. But just think how far we’ve come in just the last decade. The human genome was deciphered in 2003, and the rice genome in 2004 (although drafts of both were available earlier). And since then, there has been an ‘explosion’ of genomic data for many different crops that is throwing new light on gene function and control, and facilitating the use of genetic resources for crop improvement. You only have to think back to the early 1980s when we were making the first stabs at studying diversity at the molecular level, using isozymes and subsequently a whole range of molecular markers. These have become increasingly sophisticated such that it’s now possible to detect differences (known as polymorphisms) at the individual nucleotide (A-T-C-G) level. Where will molecular biology take us? Hardly a day passes without some new DNA revelation, or use of DNA in forensics. Most recently, analysis of DNA was used to verify the identity of a skeleton (of

It’s 60 years since the structure of DNA was elucidated by Watson and Crick, for which they and Maurice Wilkins were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1962. But just think how far we’ve come in just the last decade. The human genome was deciphered in 2003, and the rice genome in 2004 (although drafts of both were available earlier). And since then, there has been an ‘explosion’ of genomic data for many different crops that is throwing new light on gene function and control, and facilitating the use of genetic resources for crop improvement. You only have to think back to the early 1980s when we were making the first stabs at studying diversity at the molecular level, using isozymes and subsequently a whole range of molecular markers. These have become increasingly sophisticated such that it’s now possible to detect differences (known as polymorphisms) at the individual nucleotide (A-T-C-G) level. Where will molecular biology take us? Hardly a day passes without some new DNA revelation, or use of DNA in forensics. Most recently, analysis of DNA was used to verify the identity of a skeleton (of

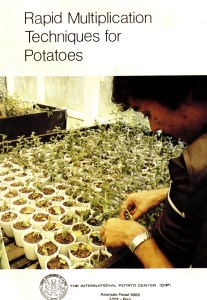

Seed production through rapid multiplication techniques was another important area, and I supported in this by seed production specialist

Seed production through rapid multiplication techniques was another important area, and I supported in this by seed production specialist

A few weeks ago, I watched

A few weeks ago, I watched

For the 2007 report we went further – producing the report only on DVD, but which also published on the IRRI web site. That provided the opportunity of returning to full color, and also including short videos, often of a staff member talking about and the significance of their research. We did the same for the 2008 report, but after I retired in 2010, the 2009 report was a hybrid: DVD plus a short booklet. And in all these reports, we provided stories focusing on an area of rice science for development, and its outcomes, rather than individual pieces of science as previously reported in the Program Reports.

For the 2007 report we went further – producing the report only on DVD, but which also published on the IRRI web site. That provided the opportunity of returning to full color, and also including short videos, often of a staff member talking about and the significance of their research. We did the same for the 2008 report, but after I retired in 2010, the 2009 report was a hybrid: DVD plus a short booklet. And in all these reports, we provided stories focusing on an area of rice science for development, and its outcomes, rather than individual pieces of science as previously reported in the Program Reports. I firmly believe that the combination of short, to-the-point messages, combined with a strong visual is an excellent way to make science accessible. Here are some examples of what I mean. As a research institute working on rice, IRRI faces several development challenges. It’s important to show the link between research and development. Click on the image to see some other examples.

I firmly believe that the combination of short, to-the-point messages, combined with a strong visual is an excellent way to make science accessible. Here are some examples of what I mean. As a research institute working on rice, IRRI faces several development challenges. It’s important to show the link between research and development. Click on the image to see some other examples.

A rather interesting experiment was reported on the

A rather interesting experiment was reported on the

And germplasm collecting was repeated in Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam in Asia, and countries in East and southern Africa including Uganda and Madagascar, as well as Costa Rica in Central America (for wild rices). We invested a lot of efforts to train local scientists in germplasm collecting methods. Long-time IRRI employee (now retired) and genetic resources specialist, Eves Loresto (right), visited Bhutan on several occasions.

And germplasm collecting was repeated in Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam in Asia, and countries in East and southern Africa including Uganda and Madagascar, as well as Costa Rica in Central America (for wild rices). We invested a lot of efforts to train local scientists in germplasm collecting methods. Long-time IRRI employee (now retired) and genetic resources specialist, Eves Loresto (right), visited Bhutan on several occasions.

The genebank now has three storage vaults (one was added in the last couple of years) for medium-term (Active) and long-term (Base) conservation. Rice varieties are grown on the IRRI farm, and carefully dried before storage. Seed viability and health is always checked, and resident seed physiologist, Fiona Hay (right, formerly at the

The genebank now has three storage vaults (one was added in the last couple of years) for medium-term (Active) and long-term (Base) conservation. Rice varieties are grown on the IRRI farm, and carefully dried before storage. Seed viability and health is always checked, and resident seed physiologist, Fiona Hay (right, formerly at the

In early 1974 I travelled to southern Peru with a taxonomist friend from the University of St Andrews, Dr Peter Gibbs (right).

In early 1974 I travelled to southern Peru with a taxonomist friend from the University of St Andrews, Dr Peter Gibbs (right).

The drive south in a small Land Rover – down the coastal desert Panamericana highway, across the Nasca plain, climbing to Arequipa, and even higher to Puno – took three days. After resting up in Puno (next to Lake Titicaca), and getting used to the 3827 m altitude, we set off for Cuyo Cuyo. Dropping down from the altiplano at well over 4000 m, Cuyo Cuyo lies at an altitude of about 3300 m. Below the village the valley drops quickly towards the ceja de la montaña – literally ‘eyebrow of the mountain’ – where the humid air of the rainforests below rises up east-facing valleys to form cloud forest.

The drive south in a small Land Rover – down the coastal desert Panamericana highway, across the Nasca plain, climbing to Arequipa, and even higher to Puno – took three days. After resting up in Puno (next to Lake Titicaca), and getting used to the 3827 m altitude, we set off for Cuyo Cuyo. Dropping down from the altiplano at well over 4000 m, Cuyo Cuyo lies at an altitude of about 3300 m. Below the village the valley drops quickly towards the ceja de la montaña – literally ‘eyebrow of the mountain’ – where the humid air of the rainforests below rises up east-facing valleys to form cloud forest.

Peter and I set up camp, so-to-speak, in the local post office where we could sleep, brew the odd cup of tea (there was a small café in the village where we could eat), and gather our specimens together, including a rudimentary drier for the extensive set of oca herbarium samples that Peter intended to make. But more of that particular story later.

Peter and I set up camp, so-to-speak, in the local post office where we could sleep, brew the odd cup of tea (there was a small café in the village where we could eat), and gather our specimens together, including a rudimentary drier for the extensive set of oca herbarium samples that Peter intended to make. But more of that particular story later. The sides of the Cuyo Cuyo valley are covered with the most wonderful system of agricultural terraces, called andenes, which must have been constructed centuries ago, in Inca times, and have been cultivated ever since. Farmers have different terraces dotted around the valley, and when I was there, at least, farmers were still using a communal rotation system. Thus in one part of the valley the terraces were covered in potatoes (year 1 after a fallow), and oca (years 2 and 3), barley or beans (year 4), or fallow (years 5-8) elsewhere. Sheep are corralled on a terrace prior to planting potatoes, and their urine and dung used as fertilizer. Whether, almost 40 years later, this remains the case I do not know.

The sides of the Cuyo Cuyo valley are covered with the most wonderful system of agricultural terraces, called andenes, which must have been constructed centuries ago, in Inca times, and have been cultivated ever since. Farmers have different terraces dotted around the valley, and when I was there, at least, farmers were still using a communal rotation system. Thus in one part of the valley the terraces were covered in potatoes (year 1 after a fallow), and oca (years 2 and 3), barley or beans (year 4), or fallow (years 5-8) elsewhere. Sheep are corralled on a terrace prior to planting potatoes, and their urine and dung used as fertilizer. Whether, almost 40 years later, this remains the case I do not know.

In preparation for Birmingham, I’d been advised to purchase and absorb a book that was published earlier that year, edited by Sir Otto Frankel and Erna Bennett [1] on genetic resources, and dedicated to NI Vavilov. And I came across Vavilov’s name for the first time in the first line of the Preface written by Frankel, and in the first chapter on Genetic resources by Frankel and Bennett. I should state that this was at the beginning of the genetic resources movement, a term coined by Frankel and Bennett at the end of the 60s when they had mobilized efforts to collect and conserve the wealth of diversity of crop varieties (and their wild relatives) – often referred to as landraces – grown all around the world, but were in danger of being lost as newly-bred varieties were adopted by farmers. The so-called Green Revolution had begun to accelerate the replacement of the landrace varieties, particularly among cereals like wheat and rice.

In preparation for Birmingham, I’d been advised to purchase and absorb a book that was published earlier that year, edited by Sir Otto Frankel and Erna Bennett [1] on genetic resources, and dedicated to NI Vavilov. And I came across Vavilov’s name for the first time in the first line of the Preface written by Frankel, and in the first chapter on Genetic resources by Frankel and Bennett. I should state that this was at the beginning of the genetic resources movement, a term coined by Frankel and Bennett at the end of the 60s when they had mobilized efforts to collect and conserve the wealth of diversity of crop varieties (and their wild relatives) – often referred to as landraces – grown all around the world, but were in danger of being lost as newly-bred varieties were adopted by farmers. The so-called Green Revolution had begun to accelerate the replacement of the landrace varieties, particularly among cereals like wheat and rice. Vavilov died of starvation in prison at the relatively young age of 55, following persecution under Stalin through the shenanigans of the charlatan Trofim Lysenko. Lysenko’s legacy also included the rejection of Mendelian genetics in the Soviet Union for many years. Eventually Vavilov was rehabilitated, long after his death, and he was commemorated on postage stamps at the time of his centennial.

Vavilov died of starvation in prison at the relatively young age of 55, following persecution under Stalin through the shenanigans of the charlatan Trofim Lysenko. Lysenko’s legacy also included the rejection of Mendelian genetics in the Soviet Union for many years. Eventually Vavilov was rehabilitated, long after his death, and he was commemorated on postage stamps at the time of his centennial. First,

First,

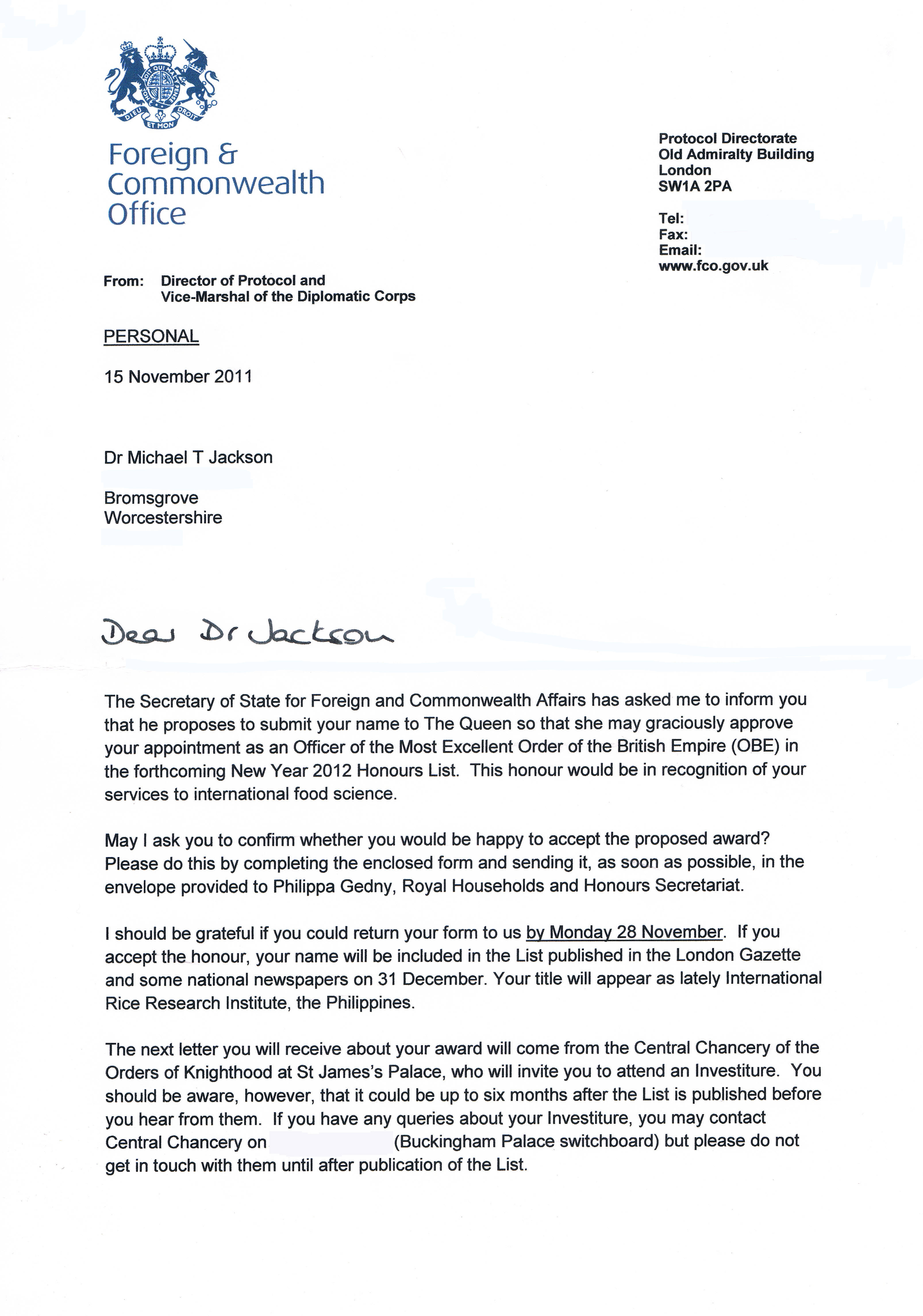

On a bright, sunny day last November (my birthday, actually) I was outside cleaning the car, when the postman passed by. He handed me several envelopes and my immediate reaction was that this was another load of the usual junk mail. So you can imagine my surprise when I came across one that seemed rather official looking. And I was even more surprised when I read what it had to say – that I had been nominated to become an Officer of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, or OBE, for services to international food science. Well, I was gob-smacked, quite emotional really. I rushed inside to tell Steph – who was equally stunned, and we set to ponder how on earth this had come about. I did some Google detective work, and was able to find out a little more about the

On a bright, sunny day last November (my birthday, actually) I was outside cleaning the car, when the postman passed by. He handed me several envelopes and my immediate reaction was that this was another load of the usual junk mail. So you can imagine my surprise when I came across one that seemed rather official looking. And I was even more surprised when I read what it had to say – that I had been nominated to become an Officer of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, or OBE, for services to international food science. Well, I was gob-smacked, quite emotional really. I rushed inside to tell Steph – who was equally stunned, and we set to ponder how on earth this had come about. I did some Google detective work, and was able to find out a little more about the