There’s nothing I enjoy more nowadays (apart from an exhilarating walk on a fine day, which have been few and far between in recent months) than to settle down with a good book and some music in the background (from Radio Paradise, Classic FM, or maybe a choice on Spotify).

My reading habits have changed over the years. Having studied English Literature in high school, I’m afraid I didn’t pick up a book for several years afterwards. Apart from one or two texts (such as the poetry of William Butler Yeats) I found the constant analysis just took all the joy out of reading.

But, with time on my hands, so to speak, when we lived in Costa Rica between 1976 and 1980, and didn’t have a television, I needed something to occupy the dark evenings. And there’s only so much beer or whisky one can safely consume.

In the capital city, San José, there was an English language bookshop selling an impressive range of books. Because they were so expensive, I didn’t want to invest in ‘cheap’ novels that I’d read once perhaps and then discard.

I was encouraged (by the wife of a visiting colleague at the agricultural institute where we lived in Turrialba, who was a professor of English Literature at Cornell University) to tackle the novels of Victorian author, Anthony Trollope (1815-1882).

I was encouraged (by the wife of a visiting colleague at the agricultural institute where we lived in Turrialba, who was a professor of English Literature at Cornell University) to tackle the novels of Victorian author, Anthony Trollope (1815-1882).

So, without further ado, I launched into Trollope’s six Palliser novels: Can You Forgive Her? (1864), Phineas Finn (1869), The Eustace Diamonds (1873), Phineas Redux (1874), The Prime Minister (1876), and The Duke’s Children (1879). The novels (as described in the Wikipedia page) . . . encompass several literary genres including: family saga, bildungsroman, picaresque, as well as satire and parody of Victorian (or English) life, and criticism of the British government’s predilection for attracting corrupt and corruptible people to power.

I then followed up with Trollope’s Chronicles of Barsetshire series of novels: The Warden (1855), Barchester Towers (1857), Doctor Thorne (1858), Framley Parsonage (1860), The Small House at Allington (1862). and The Last Chronicle of Barset (1867). These six novels (according to the Wikipedia write-up) . . . concern the dealings of the clergy and the gentry, and the political, amatory, and social manoeuvrings among them.

I also decided to delve into the Wessex novels of Thomas Hardy (1840-1928). At the time (in the 1970s), I really did enjoy them, particularly Far from the Madding Crowd and The Mayor of Casterbridge, published in 1874 and 1886, respectively. About five years ago, I decided to return to these novels, but for whatever reason, I just didn’t take to them as I had 40 years earlier.

I also decided to delve into the Wessex novels of Thomas Hardy (1840-1928). At the time (in the 1970s), I really did enjoy them, particularly Far from the Madding Crowd and The Mayor of Casterbridge, published in 1874 and 1886, respectively. About five years ago, I decided to return to these novels, but for whatever reason, I just didn’t take to them as I had 40 years earlier.

In 2017, I spent almost a whole year reading the novels of Charles Dickens, perhaps one of the greatest of the Victorian novelists.

In 2017, I spent almost a whole year reading the novels of Charles Dickens, perhaps one of the greatest of the Victorian novelists.

And what an enjoyable experience that was, considering I’d been turned off Dickens as a schoolboy. It’s hard to say which novel I enjoyed the most but, if pushed, I’d have to choose The Pickwick Papers, Dickens’ first novel.

For many years, all I read were biographies or histories – the Greeks, the Romans, medieval England, 18th century wars and early 19th (Napoleon!), and the American Civil War, among many.

But I have taken a fancy to historical novels, some executed better than others. A year or so back, when it was all the rage on TV, I tackled Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall trilogy, which cover the period between 1500 and 1535 in Tudor England, and the rise and dramatic fall of Thomas Cromwell, one time chief minister to King Henry VIII.

But I have taken a fancy to historical novels, some executed better than others. A year or so back, when it was all the rage on TV, I tackled Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall trilogy, which cover the period between 1500 and 1535 in Tudor England, and the rise and dramatic fall of Thomas Cromwell, one time chief minister to King Henry VIII.

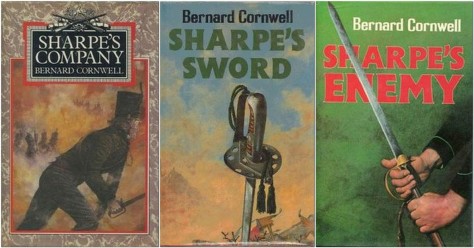

And I’ve just finished 21 novels in the Sharpe series by British author Bernard Cornwell.

1799 | 1803 | 1803

1805 | 1807 | 1809

1809 | 1809 | 1810

1811 | 1811 | 1811

1812 | 1812 | 1812

1813 | 1813 | 1814

1814 | 1815 | 1820-1821

The novels, published between 1981 and 2024 (although I haven’t read the two published in 2023 and 2024, Sharpe’s Command and Sharpe’s Storm, respectively), follow the career of Richard Sharpe from his enlistment in the army in the 1790s and his deployment in India, through the Peninsula War in Portugal and Spain, and the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 (and beyond).

Sergeant Richard Sharpe, the bastard son of a London whore, saves the life of the British commander of the British forces, Major General Arthur Wellesley (later the Duke of Wellington), at the Battle of Assaye in India in 1803, and receives a battlefield commission as an Ensign.

So why the interest in the Sharpe novels? I hadn’t come across the early ones in the 1980s while I was still living in the UK. And it wasn’t until I returned to the UK in 2010 that I came across repeat showings of a TV series of 16 episodes broadcast between 1993 and 1997, and 2006 and 2008). Not all episodes were based on one of the novels, nor necessarily followed exactly the sequence of events or characters described in the novels.

The novels relate Sharpe’s exploits with the 95th Rifles and the South Essex Regiment, his relationships with his ‘chosen men’ in particular Sergeant Patrick Harper, an Irishman from Co. Donegal, and the continual disdain, contempt even, he experiences from fellow officers who bought their commissions, and consider Sharpe an uneducated upstart. Which he is. And his persecution by his arch nemesis, Obadiah Hakeswill, played in the TV series by the late, great Pete Postlethwaite. The series starred Sean Bean as Richard Sharpe, and Daragh O’Malley as Patrick Harper. The casting of Sean Bean was an interesting choice. Why? In the novels, Sharpe is a Cockney, with dark hair. Bean has blond hair and is from Yorkshire, and portrayed Sharpe as a Yorkshireman.

L-R: Sean Bean as Major Richard Sharpe, Daragh O’Malley as Sergeant Patrick Harper, and Pete Postlethwaite as Sergeant Obadiah Hakeswill.

Through the novels, Sharpe follows Wellesley through Portugal and Spain, earning notoriety and fame for his heroic exploits, particularly the capture (with Sergeant Harper) of a French eagle at the Battle of Talavera in 1809.

By Waterloo, Sharpe has risen through the ranks and has become a Lieutenant Colonel.

Anyway, having enjoyed the TV programs, I thought it would be interesting to see how faithfully they had followed the novels. So I decided to read them in chronological order, not publication order. I haven’t yet come across those published over the past couple of years that encompass events much earlier in the chronology.

The novels are full of details of the various battles that Wellington fought. Cornwell visited a number of the battlefields, and clearly has an impressive knowledge of military history and equipment. He’s always explaining the contrast between the slow-loading, but very much more accurate Baker rifle with a longer range used by the Rifles, and the muskets used by most recruits. This level of detail certainly lends a veracity to the narratives.

The Napoleonic Wars have long been an interest of mine, and working my way through the Sharpe novels has given a another dimension to that period of conflict in the early 19th century.