Home of the potato

The Andes of South America are the home of the potato that has supported indigenous civilizations for thousands of years. As many as 4,000 native potato varieties are still grown. The region around Lake Titicaca in southern Peru and northern Bolivia is particularly rich in genetic diversity, and the wild potatoes from here are valuable for their disease and pest resistance [1].

The Andes of South America are the home of the potato that has supported indigenous civilizations for thousands of years. As many as 4,000 native potato varieties are still grown. The region around Lake Titicaca in southern Peru and northern Bolivia is particularly rich in genetic diversity, and the wild potatoes from here are valuable for their disease and pest resistance [1].

For three years, from 1973-1975 I had the privilege of living and working in Peru (fulfilling an ambition I’d had since I was a boy) and studying the potato in its homeland. My work took me all over the mountains to collect potato varieties (for conservation in the germplasm collection of the International Potato Center (CIP), and to carry out studies of potato cultivation that I hoped would throw some light on different aspects of potato evolution [2].

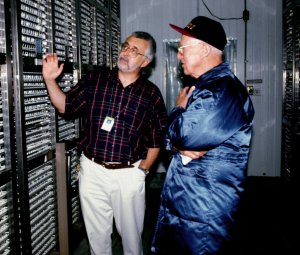

I joined CIP in January 1973 as Associate Taxonomist, charged with the task of collecting potato varieties and helping them to maintain the large germplasm collection, that grew to at least 15,000 separate entries (or clonal accessions), but was reduced to a more manageable number through the elimination of duplicate samples. The germplasm collection was planted each year from October through April, coinciding with the most abundant rains, in the field in Huancayo, central Peru at an altitude of more than 3,100 meters.

I joined CIP in January 1973 as Associate Taxonomist, charged with the task of collecting potato varieties and helping them to maintain the large germplasm collection, that grew to at least 15,000 separate entries (or clonal accessions), but was reduced to a more manageable number through the elimination of duplicate samples. The germplasm collection was planted each year from October through April, coinciding with the most abundant rains, in the field in Huancayo, central Peru at an altitude of more than 3,100 meters.

Potato collection at CIP, grown in the field at Huancayo, central Peru, at 3100 m. Taken around mid 1980s.

When CIP was founded in 1971, several germplasm collections from various institutes in Peru and elsewhere were donated to the new collection, but from 1973 CIP organized a program of collecting throughout Peru – and I was fortunate to be part of  that endeavour. In May 1973 I joined my colleague Zosimo Huaman to collect potatoes in the Departments of Ancash and La Libertad, to the north of Lima. The highest mountains in Peru are found in Ancash, and our route took us through into the Callejón de Huaylas (between two ranges of the highest mountains in Peru, the Cordillera Blanca on the east, and Cordillera Negra on the west), and over the mountains to valleys on the eastern flanks. This was my first experience of collecting germplasm, and it was exhilarating. I think we did quite well in terms of the varieties collected, and the photograph below illustrates some of their immense genetic diversity.

that endeavour. In May 1973 I joined my colleague Zosimo Huaman to collect potatoes in the Departments of Ancash and La Libertad, to the north of Lima. The highest mountains in Peru are found in Ancash, and our route took us through into the Callejón de Huaylas (between two ranges of the highest mountains in Peru, the Cordillera Blanca on the east, and Cordillera Negra on the west), and over the mountains to valleys on the eastern flanks. This was my first experience of collecting germplasm, and it was exhilarating. I think we did quite well in terms of the varieties collected, and the photograph below illustrates some of their immense genetic diversity.

Genetic diversity in cultivated potatoes

The following year I traveled with just a driver, Octavio (who was unfortunately killed in a road accident a couple of years later) further north into the Department of Cajamarca during April-May 1974. The photograph below shows the view, in the early morning sun, south towards Cajamarca city. The mist hanging over the city comes from hot springs that were utilized centuries ago by the Incas to build bath houses.

We collected potatoes in the field at the time of harvest, but also in markets (here is shown the market of Bambamarca), and from farmers’ own potato stores. Incidentally, the tall straw hats are very typical Cajamarca, as are the russet-colored ponchos.

Collecting potatoes in Cajamarca, northern Peru in May 1974.

In January 1974 I made a trip south, with Dr Peter Gibbs, a taxonomist from the University of St Andrews, Scotland, who was interested in the tri-styly pollination  of a minor Andean tuber crop called oca (Oxalis tuberosa). We went to the village of Cuyo Cuyo, more than 100 km north of Puno in southern Peru. Dropping down from the altiplano, the road hugs the sides of the valley, and is often blocked by landslides (a very common occurrence throughout Peru in the rainy season). Along the way – and due to the warmer air rising from the selva (jungle) to the east – the vegetation is quite luxurious in places, as the white begonia below shows (the flowers were about 8 cm in diameter). Eventually the valley opens out, with terraces on all sides. These terraces (or andenes) are ancient structures constructed by the Incas to make the valley more productive.

of a minor Andean tuber crop called oca (Oxalis tuberosa). We went to the village of Cuyo Cuyo, more than 100 km north of Puno in southern Peru. Dropping down from the altiplano, the road hugs the sides of the valley, and is often blocked by landslides (a very common occurrence throughout Peru in the rainy season). Along the way – and due to the warmer air rising from the selva (jungle) to the east – the vegetation is quite luxurious in places, as the white begonia below shows (the flowers were about 8 cm in diameter). Eventually the valley opens out, with terraces on all sides. These terraces (or andenes) are ancient structures constructed by the Incas to make the valley more productive.

In Cuyo Cuyo, I studied the varieties growing in farmers’ fields, and their uses [3].

Getting to some locations by four-wheel drive vehicle was often difficult. Then it was either ‘shanks’ pony’, or real pony. I do remember that I became very sore after many hours in the saddle. Incidentally, I still have that straw hat and it’s as good as the day I bought it in January 1973.

But studying potato systems, and working with farmers was fascinating. Here I am collecting flower buds, and preserving them in alcohol ready to make chromosome counts in the laboratory, back in Lima.

The next photograph shows a community we visited close to Chincheros, near Cuzco in southern Peru. While farmers grew commercial varieties to send to market in Cuzco – the large plantings of potatoes in the distance -closer to their dwellings they grew complex mixtures of varieties, with different cooking and eating qualities.

Most farmers do not have access to mechanization, apart from manual labor and oxen to pull ploughs. In any case, much of the land in these steep valleys is unsuitable for mechanization. For centuries, farmers use the chakitaqlla or foot plough illustrated by Peruvian chronicler Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala in the early 17th century. There are many different foot ploughs in used throughout Peru. The foot plough shown below in one of Poma de Ayala’s illustrations is the same as that used by farmers in Cuyo Cuyo. The photograph underneath shows farmers near Huanuco in central Peru.

I never collected wild potatoes as such, but it was fun on two occasions to accompany my thesis supervisor and mentor, Jack Hawkes (a world-renowned expert on the taxonomy and evolution of potatoes, and one of the founders of the genetic resources movement in the 1960s) on short trips. In January 1973 we visited Cuzco, and Jack found Solanum raphanifolium growing among the ruins of the Inca fortress of Sacsayhuaman.

Sacsayhuaman at Cuzco

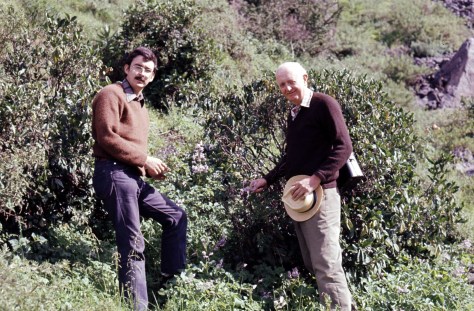

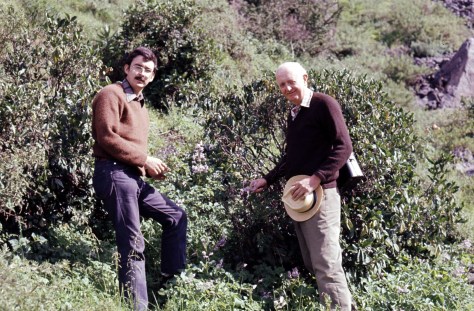

Early 1975 (during one of his annual trips to CIP) Jack, Juan Landeo (then a research assistant, who later became one of CIP’s potato breeders), and I traveled over four days through the central Andes just north and east of Lima, in the Departments of Cerro de Pasco, Huanuco, and Lima. It was fascinating watching an expert at work, especially someone so familiar with the wild potatoes and their ecology. We’d be driving along, and suddenly Jack would say “Stop the car! I can smell potatoes”. And more than nine times out of ten we’d find clumps of wild potatoes after just a few minutes of searching. Here we are (looking rather younger) about to make a herbarium collection just south of Cerro de Pasco (I don’t remember which wild species, however).

Markets are always fascinating places to collect germplasm of many different crops. The next two photographs show colorful diversity in maize and peppers.

Among the many you can find in the market is chuño, a type of freeze-dried potato, made from several varieties of so-called bitter potatoes, which have a high concentration of alkaloids which must be removed before eating. This is done by first leaving the tubers on the ground on frosty nights to freeze, and then thaw the following morning. After several cycles of freezing and thawing the tubers are then soaked for several weeks in fast-flowing streams to leach out the bitter compounds. Afterwards, they are left to dry in the sun, and in this preserved state will last for months. This photograph was taken in the Sunday market at Pisac, near Cuzco.

Clearly the potato is an ancient crop in Peru (and other countries of the South American Andes), and domesticated several thousand years ago. It was revered by ancient civilizations, as these anthropomorphic potato pots (or huacos) show. The national anthropological museum in Lima has a fine collection of these pots showing a vast array of different crop plants. It also holds an extensive collection of erotic ceramics for which the Incas, Moche, and other coastal civilizations were equally famous.

After the conquest of the Incan empire by Francisco Pizarro González in the 16th century, the Spanish plundered all the gold and other precious items they could find, and sent everything back to Spain. It’s often said, however, that the value of all this gold fades into insignificance compared to the value of the potato crop today worldwide. The real treasure of the Incas has certainly been put to better use.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

[1] Jackson, M.T., J.G. Hawkes, B.S. Male-Kayiwa & N.W.M. Wanyera, 1988. The importance of the Bolivian wild potato species in breeding for Globodera pallida resistance. Plant Breeding 101, 261-268.

[2] Jackson, M.T., J.G. Hawkes & P.R. Rowe, 1977. The nature of Solanum x chaucha Juz. et Buk., a triploid cultivated potato of the South American Andes. Euphytica 26, 775-783.

[3] Jackson, M.T., J.G. Hawkes & P.R. Rowe, 1980. An ethnobotanical field study of primitive potato varieties in Peru. Euphytica 29, 107-113.

Oatcakes? These aren’t the crispy biscuits you buy in Scotland. Oh no! They are a delicious, thin, grilled ‘pancake’ made from fermented oat flour, served hot with delicious fillings of bacon, sausages, cheese, and eggs, and have been a traditional Potteries delicacy for decades. Just watch this audio slideshow to learn how they are made (and what is happening to The Hole in the Wall) , and why Potteries folk adore them. It’s believed that the idea of oatcakes was brought back to the Potteries by soldiers of the Staffordshire Regiment who had served in India. They look like the Ethiopian injera, which is made from the indigenous cereal teff (Eragrostis tef). These points are raised in the slideshow and the accompanying article in The Guardian.

Oatcakes? These aren’t the crispy biscuits you buy in Scotland. Oh no! They are a delicious, thin, grilled ‘pancake’ made from fermented oat flour, served hot with delicious fillings of bacon, sausages, cheese, and eggs, and have been a traditional Potteries delicacy for decades. Just watch this audio slideshow to learn how they are made (and what is happening to The Hole in the Wall) , and why Potteries folk adore them. It’s believed that the idea of oatcakes was brought back to the Potteries by soldiers of the Staffordshire Regiment who had served in India. They look like the Ethiopian injera, which is made from the indigenous cereal teff (Eragrostis tef). These points are raised in the slideshow and the accompanying article in The Guardian. But there’s another Staffordshire delicacy – love it or hate it (in my case, ‘hate it’) – and that’s Marmite, a yeast extract by-product of the brewing industry. Marmite comes from Burton-upon-Trent, and the ‘Marmite odour’ is quite rich at times during the summer as you drive through the town.

But there’s another Staffordshire delicacy – love it or hate it (in my case, ‘hate it’) – and that’s Marmite, a yeast extract by-product of the brewing industry. Marmite comes from Burton-upon-Trent, and the ‘Marmite odour’ is quite rich at times during the summer as you drive through the town.

I’m not really a movie buff. In fact I can’t remember the last time I went to the cinema. It might even have been 1977 when I saw Star Wars in San José, Costa Rica. But I do catch the odd movie from time-to-time on the TV, and I particularly like westerns and musicals (although I still haven’t seen The Sound of Music.) The musicals of the thirties were something special and surrealistic – especially those directed by

I’m not really a movie buff. In fact I can’t remember the last time I went to the cinema. It might even have been 1977 when I saw Star Wars in San José, Costa Rica. But I do catch the odd movie from time-to-time on the TV, and I particularly like westerns and musicals (although I still haven’t seen The Sound of Music.) The musicals of the thirties were something special and surrealistic – especially those directed by

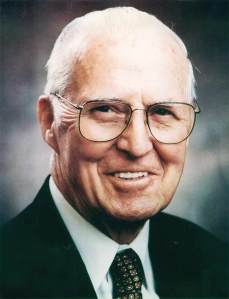

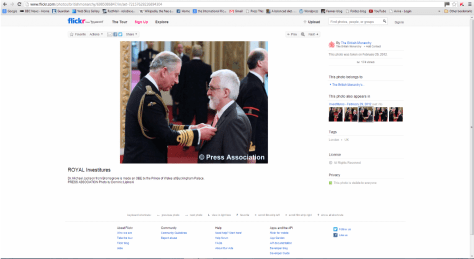

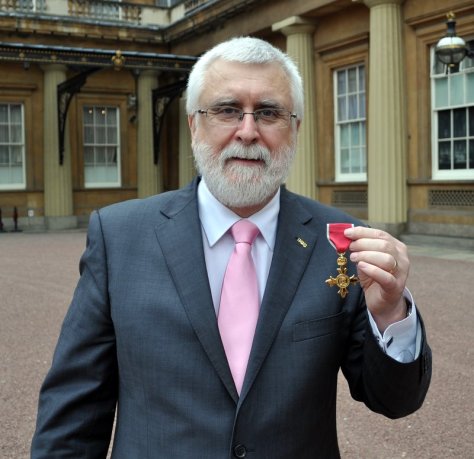

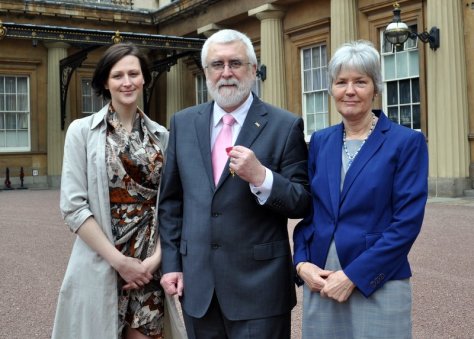

On a bright, sunny day last November (my birthday, actually) I was outside cleaning the car, when the postman passed by. He handed me several envelopes and my immediate reaction was that this was another load of the usual junk mail. So you can imagine my surprise when I came across one that seemed rather official looking. And I was even more surprised when I read what it had to say – that I had been nominated to become an Officer of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, or OBE, for services to international food science. Well, I was gob-smacked, quite emotional really. I rushed inside to tell Steph – who was equally stunned, and we set to ponder how on earth this had come about. I did some Google detective work, and was able to find out a little more about the

On a bright, sunny day last November (my birthday, actually) I was outside cleaning the car, when the postman passed by. He handed me several envelopes and my immediate reaction was that this was another load of the usual junk mail. So you can imagine my surprise when I came across one that seemed rather official looking. And I was even more surprised when I read what it had to say – that I had been nominated to become an Officer of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, or OBE, for services to international food science. Well, I was gob-smacked, quite emotional really. I rushed inside to tell Steph – who was equally stunned, and we set to ponder how on earth this had come about. I did some Google detective work, and was able to find out a little more about the

I joined CIP in January 1973 as Associate Taxonomist, charged with the task of collecting potato varieties and helping them to maintain the large germplasm collection, that grew to at least 15,000 separate entries (or clonal accessions), but was reduced to a more manageable number through the elimination of duplicate samples. The germplasm collection was planted each year from October through April, coinciding with the most abundant rains, in the field in Huancayo, central Peru at an altitude of more than 3,100 meters.

I joined CIP in January 1973 as Associate Taxonomist, charged with the task of collecting potato varieties and helping them to maintain the large germplasm collection, that grew to at least 15,000 separate entries (or clonal accessions), but was reduced to a more manageable number through the elimination of duplicate samples. The germplasm collection was planted each year from October through April, coinciding with the most abundant rains, in the field in Huancayo, central Peru at an altitude of more than 3,100 meters.

that endeavour. In May 1973 I joined my colleague Zosimo Huaman to collect potatoes in the Departments of Ancash and La Libertad, to the north of Lima. The highest mountains in Peru are found in Ancash, and our route took us through into the

that endeavour. In May 1973 I joined my colleague Zosimo Huaman to collect potatoes in the Departments of Ancash and La Libertad, to the north of Lima. The highest mountains in Peru are found in Ancash, and our route took us through into the

of a minor Andean tuber crop called oca (Oxalis tuberosa). We went to the village of Cuyo Cuyo, more than 100 km north of Puno in southern Peru. Dropping down from the altiplano, the road hugs the sides of the valley, and is often blocked by landslides (a very common occurrence throughout Peru in the rainy season). Along the way – and due to the warmer air rising from the selva (jungle) to the east – the vegetation is quite luxurious in places, as the white begonia below shows (the flowers were about 8 cm in diameter). Eventually the valley opens out, with terraces on all sides. These terraces (or andenes) are ancient structures constructed by the Incas to make the valley more productive.

of a minor Andean tuber crop called oca (Oxalis tuberosa). We went to the village of Cuyo Cuyo, more than 100 km north of Puno in southern Peru. Dropping down from the altiplano, the road hugs the sides of the valley, and is often blocked by landslides (a very common occurrence throughout Peru in the rainy season). Along the way – and due to the warmer air rising from the selva (jungle) to the east – the vegetation is quite luxurious in places, as the white begonia below shows (the flowers were about 8 cm in diameter). Eventually the valley opens out, with terraces on all sides. These terraces (or andenes) are ancient structures constructed by the Incas to make the valley more productive.