Once there were hundreds. Now there’s just Court No. 15, the last remaining (and carefully restored) courtyard of working people’s houses just south of Birmingham city center on the corner of Hurst and Inge Streets.

Court 15 of the Birmingham Back to Backs, with the Birmingham Hippodrome on the north (right) side. Just imagine what the area must have looked like in earlier decades with street upon street of these terraced and back to back houses.

This is the Birmingham Back to Backs, owned by the National Trust, which we had the pleasure of visiting a couple of days ago, and enjoyed a tour led by knowledgeable guide Fran Payne. This National Trust property should be on everyone’s NT bucket list.

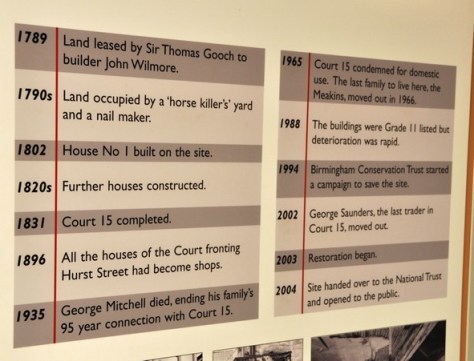

Court 15 was completed in 1831 and its houses were occupied as recently as the mid-1960s, when they were condemned. Commercial premises on the street side were still being used as late as 2002.

Court 15 was a communal space for upwards of 60-70 men, women and children, living on top of one another, in houses that were literally just one room deep: built on the back of the terraces facing the street. Just imagine the crowding, the lack of running water and basic sanitation, leading to the spread of social diseases like tuberculosis or cholera that were common in the 19th century. Just three outside toilets for everyone.

Since coming into its hands in 2004, the National Trust has developed an interesting tour of three of the Court 15 houses, taking in the lives of families from the 1840s, 1870s, and 1930s known to be living there then. The tour, encompassing very narrow and steep (almost treacherous) stairs over three floors, takes you into the first 1840s house, up to the attic bedrooms, and through to that representing the 1870s. You then work your way down to the ground floor, and into the house next door. From the attic in that house, the tour passes into the former commercial premises of tailor George Saunders who came to Birmingham from St Kitts in the Caribbean and made a name for himself in bespoke tailoring. When Saunders vacated Court 15 in 2002 he left much of the premises as it was on his last day of trading.

A Jewish family by the name of Levi, was known to reside in one of the houses during the 1840s. The Levis had one daughter and three sons, and like many other families, Mr Levi practiced his trade (of making clock and watch hands) from his home.

On the top attic floor of this house there are two rooms still accessible on the street side, but have never been renovated.

In the next 1870s house, occupied by the Oldfields, who had many children – and lodgers! – there is already a coal-fired range in the kitchen, and paraffin lamps were used throughout for lighting. The children slept head-to-toe in a bed in the attic room, shared with the married lodgers. Modesty was maintained by a curtain.

By the 1930s, there was already electricity (and running water) in the house, occupied by an elderly bachelor George Mitchell.

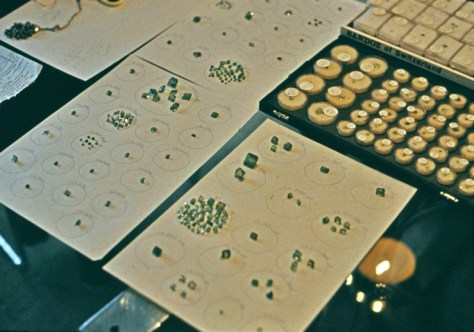

The premises of George Saunders are full of all the paraphernalia of the tailoring business. An old sewing machine, and another for making buttonholes. Patterns for bespoke suits handing from the walls, and bolts of cloth stacked on shelves. There are some half-finished garments, others ready to collect. Until his death, George worked with the National Trust to document the last years of the Back to Backs.

Throughout the houses there are many contemporary pieces of furniture and ornaments. My eye was caught by this particularly fine pair of (presumably) Staffordshire rabbits.

Finally, no visit to the Birmingham Back to Backs would be complete without a look inside Candies, a Victorian sweet shop on the corner of Hurst and Inge Streets at No. 55, purveyor of fine sweets that I remember from my childhood. What a sensory delight! In fact, tours of the Back to Backs start from outside Candies, so there’s no excuse.

And finally, what about that ‘rule of thumb’ I referred to in the title of this post. Well, while we were looking at the sleeping arrangements for the Oldfield children in the 1870s, Fran Payne reached under the bed for the gazunda, the communal chamber pot (‘goes under’). In the darkness, she told us, this how you could tell, with the tip of your thumb, whether a chamber pot was full or not. Dry: OK. Wet: time to go downstairs to the outside toilet in the courtyard.

I mentioned that our visit to the Back to Backs was very enjoyable, but it’s not somewhere that I would have made a special trip. We had to be in Birmingham on another errand, and since it was just a hop and a skip from the central Post Office, we took the opportunity. The Birmingham Back to Backs are a special relic of this great city of 1,000 trades.

The

The  The RHS Malvern Spring Festival is the second in the Society’s 2018 calendar and, set against the magnificent Malvern Hills . . . is packed with flowers, food, crafts and family fun. And yes, we did have fun. So rather than describe what we did and saw, here’s just a selection of the many photos I took during the day.

The RHS Malvern Spring Festival is the second in the Society’s 2018 calendar and, set against the magnificent Malvern Hills . . . is packed with flowers, food, crafts and family fun. And yes, we did have fun. So rather than describe what we did and saw, here’s just a selection of the many photos I took during the day.

It’s not my intention here to provide a detailed history of Rievaulx Abbey. English Heritage owns and manages the site, and a detailed history of Rievaulx’s founding and growth can be found on its

It’s not my intention here to provide a detailed history of Rievaulx Abbey. English Heritage owns and manages the site, and a detailed history of Rievaulx’s founding and growth can be found on its

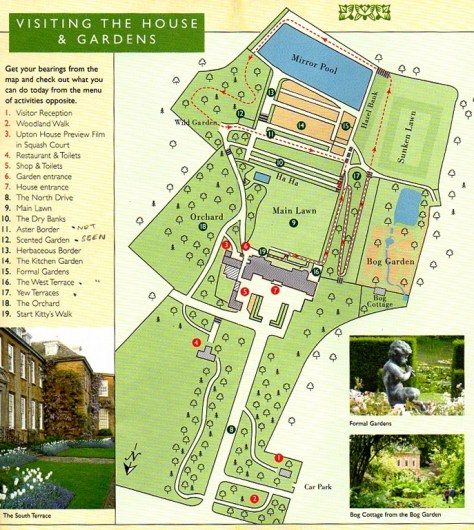

So, with much more inclement weather forecast, Steph and I decided that we’d better take advantage of yesterday’s decent weather and head out for a walk, and visit yet another National Trust property:

So, with much more inclement weather forecast, Steph and I decided that we’d better take advantage of yesterday’s decent weather and head out for a walk, and visit yet another National Trust property:

Elgar was born in June 1857 in a small cottage, The Firs, in the village of

Elgar was born in June 1857 in a small cottage, The Firs, in the village of

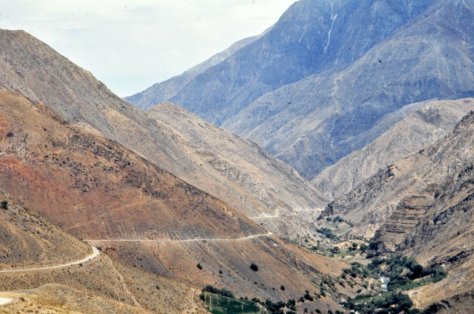

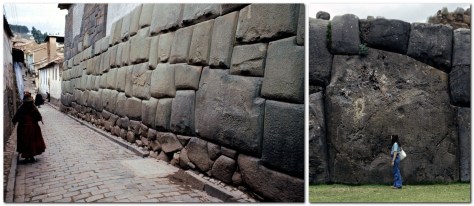

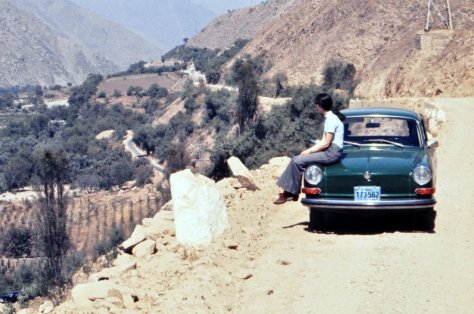

Almost 50 years after my father visited Brazil, I made my first trip there in early 1979, when I attended a meeting of the Latin American Potato Association, ALAP. Its meeting that year was held in

Almost 50 years after my father visited Brazil, I made my first trip there in early 1979, when I attended a meeting of the Latin American Potato Association, ALAP. Its meeting that year was held in