Over the past 14 years, Steph and I have made several awesome road trips across the USA, covering 36 states and visiting many national parks and national monuments. I can’t decide which trip I enjoyed most, but the two we made to the American Southwest stand out for the amazing desert landscapes and the fascinating archaeology there.

The Ancestral Puebloans (formerly known as the Anasazi) inhabited the southwest in a region known as the Four Corners (where Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Utah meet) from about 500 CE and were known for their pit houses, and cliff dwellings constructed in alcoves along the walls of sandstone canyons.

Where did these people come from, who taught them subsistence agriculture (based on the ‘three sisters‘ polyculture of corn, beans, and squashes), and why did they abandon many of their settlements around 1300 CE?

Since corn (Zea mays) was domesticated in southern Mexico, thousands of years earlier, the Ancestral Puebloans must have had links with other peoples to the south with whom they traded.

I’m still trying to understand North American indigenous cultures, so I’m not going to make any attempt here to explain the Ancestral Puebloans as such. But I have included links where you can find more information.

In 2011, we spent about 10 days exploring Arizona and New Mexico. This past May, over seven days, we drove from Las Vegas, NV to Denver, CO across Utah.

We first came across Ancestral Pueblo settlements on that 2011 trip when, heading north from Flagstaff, AZ to the Grand Canyon, we took a diversion east and visited Wupatki National Monument, and three different sites there: Wukoki Pueblo, Wupatki Pueblo, and Box Canyon. It was a bustling community at its zenith in the 12th century CE, but had been largely abandoned by the first quarter of the 13th.

Then it was on to Canyon de Chelly National Monument in northeast Arizona. We viewed three settlements from the rim of the canyon. Mummy Cave, high on the canyon wall (upper image below), was occupied for a thousand years from about 300 CE, so I have read. Antelope House (middle image), and another, White House ruin (lower image, built in the early 11th century CE), nearer the canyon floor, and the only ruin accessible (from the canyon rim) to tourists on foot. Other visits to the canyon have to be organized with local Navajo tour guides.

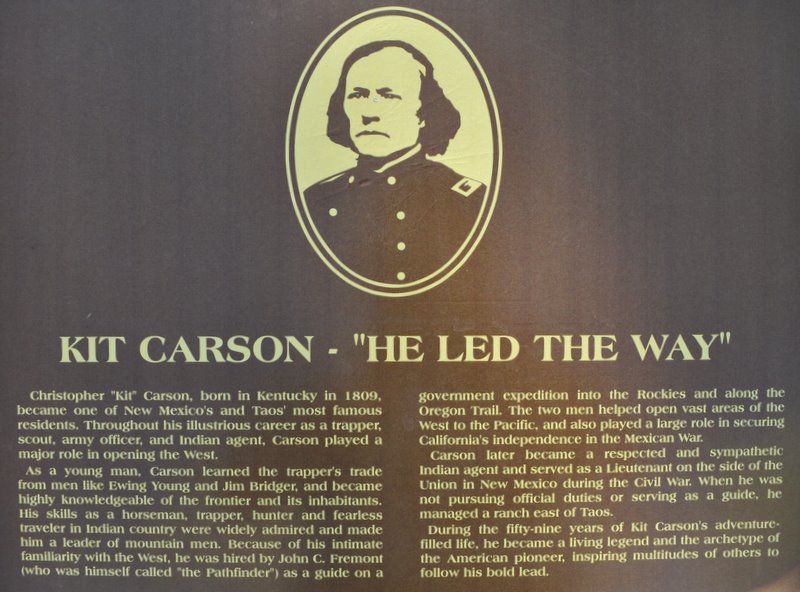

On that same trip we drove into New Mexico, passing nearby but not visiting two World Heritage sites: Chaco Culture National Historical Park, a major center of Ancestral Puebloan culture dating between 850 and 1250 CE, and Taos Pueblo, home to Native Americans for over a thousand years. Near Los Alamos, we did visit Bandelier National Monument, a site dated to a later Ancestral Puebloan era, from around 1150 CE to 1600 CE, with rooms carved into the cliff face.

This year, however, Mesa Verde National Park in southwest Colorado (some 35 miles west of Durango) was very much on our itinerary. Ancestral Puebloan remains there span the whole 750 year occupation from about 550 CE up until c. 1300 CE.

The route I’d planned south to Durango took us from Grand Junction in northwest Colorado over the Million Dollar Highway, a 25 mile section of US 550 between Ouray and Silverton in the San Juan Mountains. I had expected the 165 mile drive to take all day, and had planned accordingly, since the Million Dollar Highway is claimed to be one of the most challenging—and dangerous—highways in the USA. In many places there are no guard rails. You can view the route in a couple of videos here. Just scroll down to ‘Day 5’.

However, it took only half a day, so we decided to head to Mesa Verde that same afternoon rather than waiting for the next morning. I guess we must have arrived at the Visitor Center by about 3 pm. Like our visit to Bryce Canyon a few days earlier, arriving mid-afternoon was really quite fortuitous. Many visitors were already leaving and none of the parking lots at the various sites along the park drive was busy, making for a tranquil appreciation of all the park had to offer. And, as an added bonus, visiting Mesa Verde that afternoon freed up time the next day for the 260 mile drive east to Cañon City.

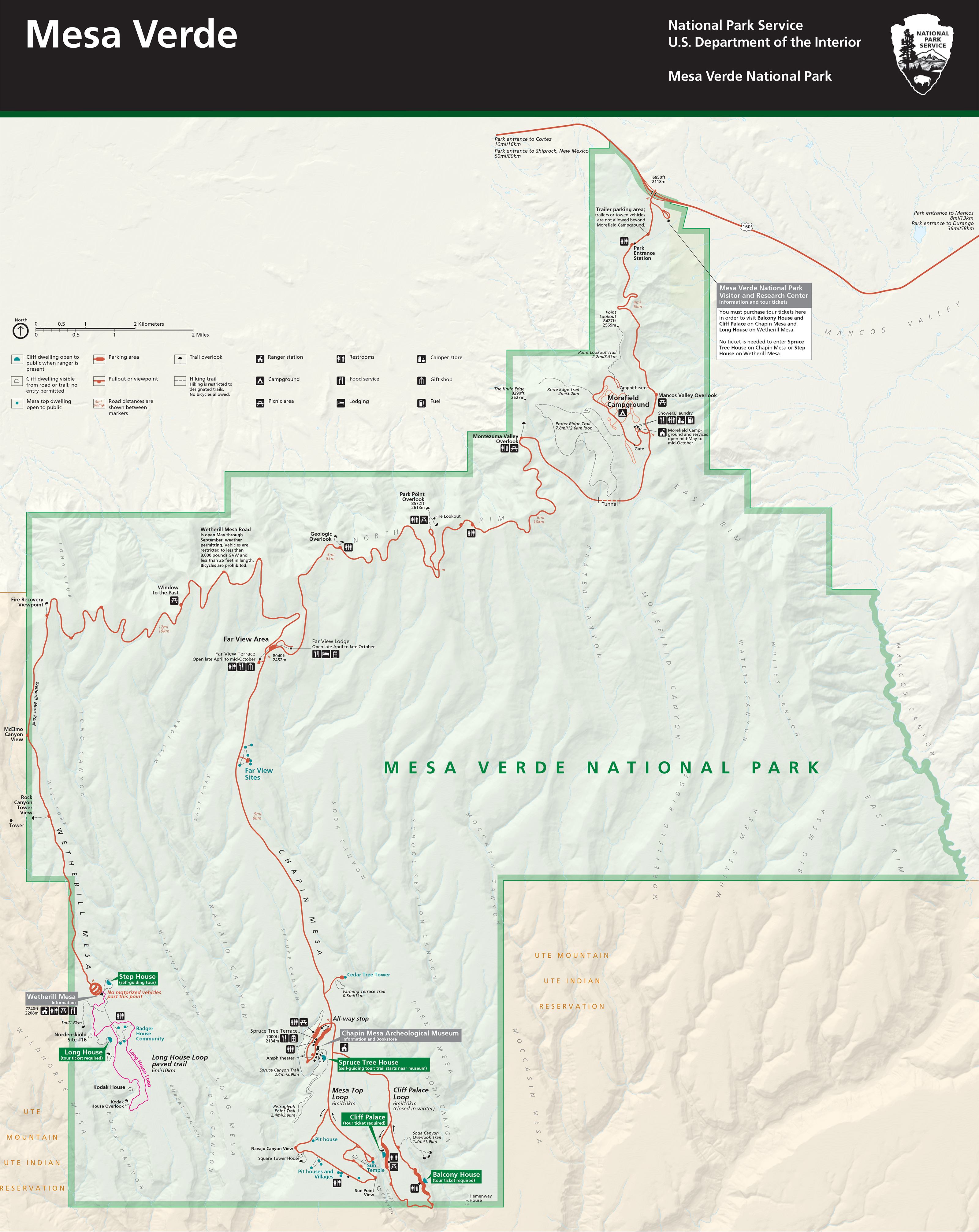

From the Visitor Center it’s a 23 mile drive to the southernmost point on the Mesa Top Loop where some of the most complete ruins are located. The park has 5000 known archaeological sites, and over 600 cliff dwellings. Although famous for its cliff dwellings, these were occupied for a short period, not long before the people abandoned Mesa Verde for reasons not fully understood, and moved south. Click on the map below to open an enlarged version.

The park road climbs steeply on to the mesa top, which lies around 7-8000 ft above sea level. So, in summer it’s blisteringly hot, and bitingly cold in winter. No wonder it was a challenge to live here.

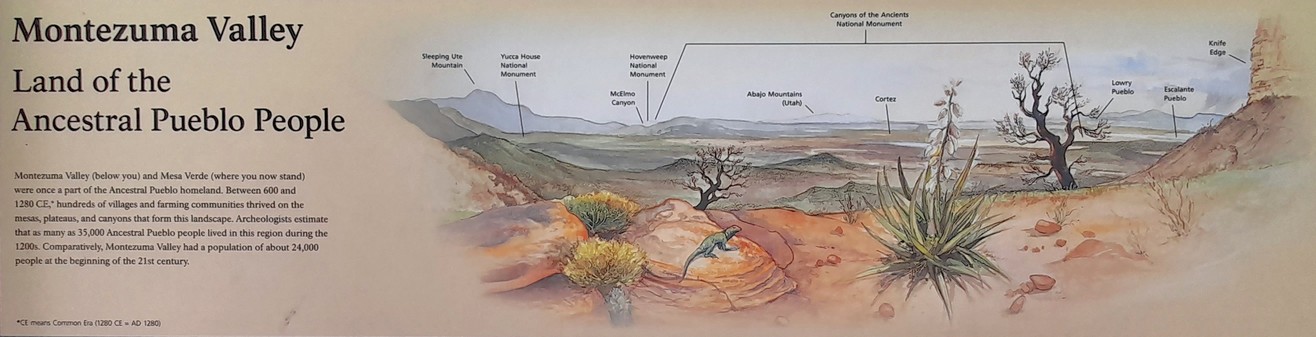

On the way south, one of our first stops was the Montezuma Valley Overlook, from where there is an impressive view of the landscape west into Utah. Click on this image to open a larger version.

I recently came across the video below, posted by explorer and YouTuber Andrew Cross (Desert Drifter – more later). On a recent visit to southeast Utah in Montezuma Canyon, a group from The Archaeological Conservancy explored the extensive settlements there.

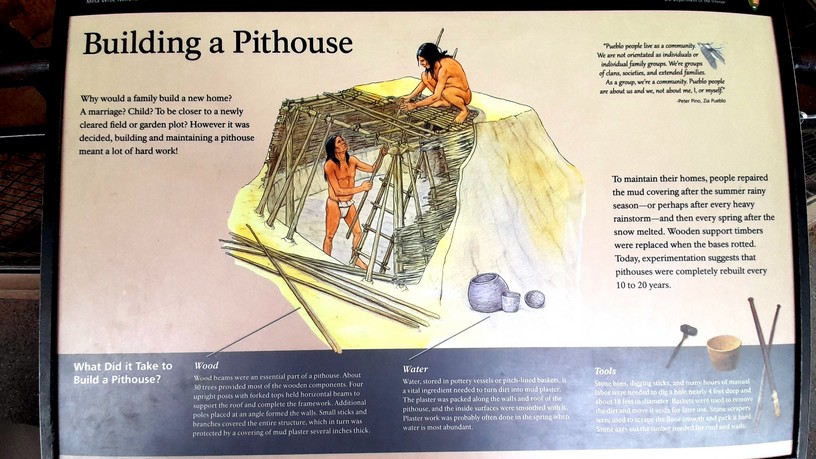

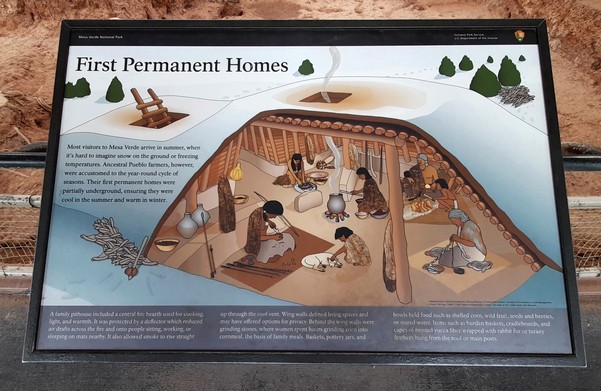

The first Ancestral Puebloans lived in pit houses on the mesa tops, and constructed partially underground. The earliest date from the 6th century CE.

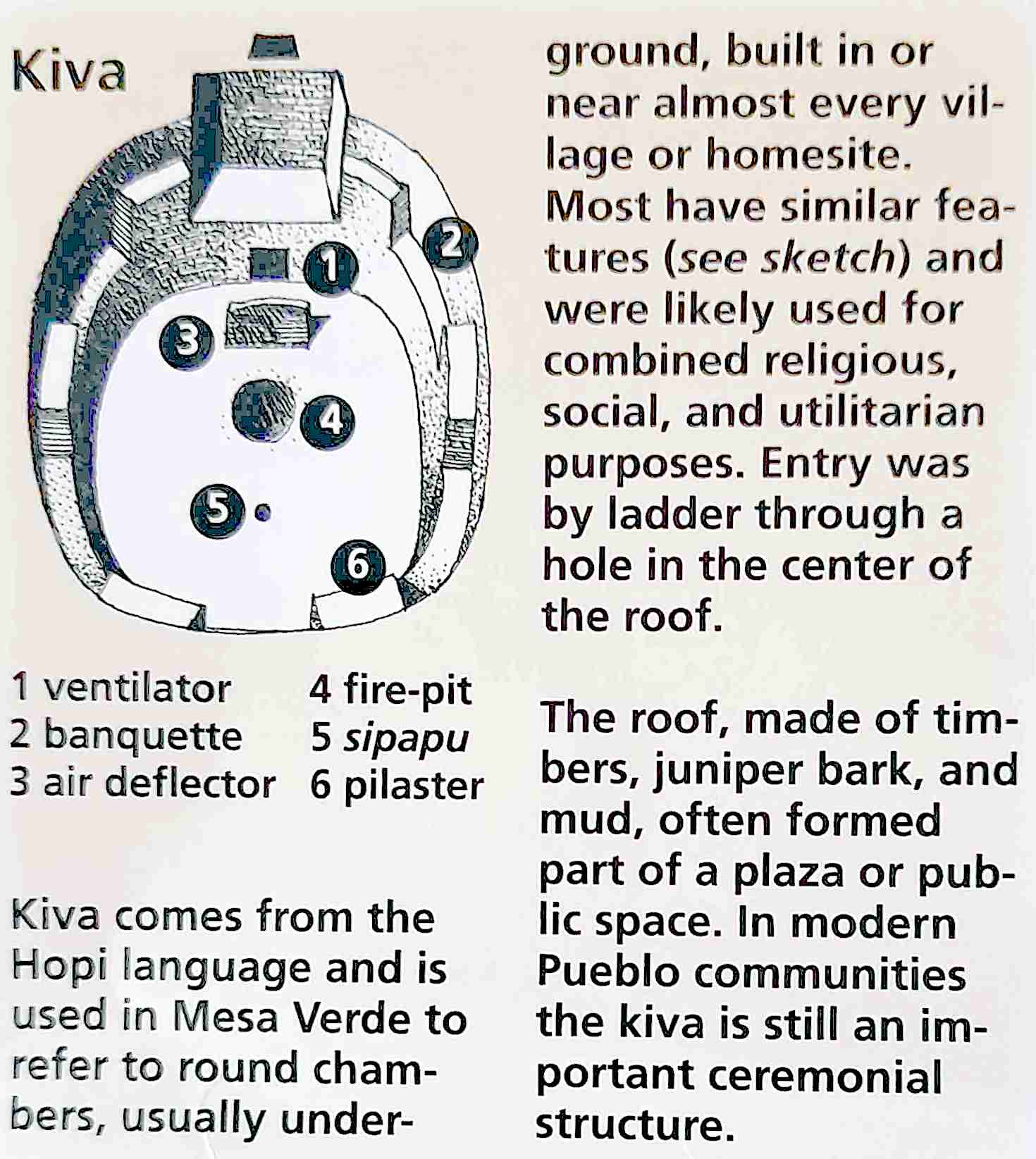

Then, several centuries later, larger villages were established (like those we saw at Wupatki) but also the cliff dwellings comprised of multiple houses and rooms, and round, ceremonial courtyards known as kivas, and which can also be seen in the Bandelier images above.

Two of the sites on the Mesa Top Loop, the Cliff Palace and Balcony House are only accessible on a guided tour, which we didn’t take. In any case, access to both requires scrambling up ladders, which I would not have managed (I’m currently using a stick due to an on-going back problem). The Cliff Palace and several other buildings close by can be viewed from an overlook. All very impressive.

The Ancestral Puebloans gained access to the cliff dwellings through handholds in the rock face, or using ropes. Certainly their difficult accessibility must have been a key feature for defence.

So, from the original sparsely settled villages of pit houses, to the more densely populated cliff dwellings, it’s estimated that Mesa Verde was once home to thousands of families. But by about 1300 CE they had upped sticks and moved on. Why? No-one really knows but it could have been due to drought affecting agricultural productivity. Or maybe conflicts had broken out, thus the reasons for more defensive villages in the cliff dwellings. The Ancestral Puebloans certainly left a strong legacy behind.

Earlier I mentioned Andrew Cross (right) and his Desert Drifter channel. It’s certainly worth a watch. His videos document his backpacking trips into canyon country looking for signs of the Ancestral Puebloans (and other indigenous peoples) that he has discovered through careful study of Google Earth images.

And he has come across some remarkable settlements, often sufficient to support just one or two families at most, who left behind evidence of their occupancy 1000 years ago in the form of pottery shards (typically black stripes on a white background), arrow heads, various tools for grinding corn, and ancient corn cobs as well. And the Puebloans also left behind incredible pictographs (paintings) and petroglyphs (etched into the rock surface) of fantastical humans, animals, and symbols. Hand prints are common everywhere.

The day after visiting Mesa Verde, we set off early from Durango to cross the mountains east of Pagosa Springs, before heading northeast to Cañon City.

The day after visiting Mesa Verde, we set off early from Durango to cross the mountains east of Pagosa Springs, before heading northeast to Cañon City.

About 16 miles short of Pagosa Springs we saw a road sign to Chimney Rock National Monument, which was just under 4 miles south from the main highway, US 160. I hadn’t noticed this when planning the trip, but as we now had extra time, we decided to explore. We were not disappointed.

Chimney Rock, an outlier from the Chaco Canyon Regional system, ‘. . . covers seven square miles and preserves 200 ancient homes and ceremonial buildings, some of which have been excavated for viewing and exploration: a Great Kiva, a Pit House, a Multi-Family Dwelling, and a Chacoan-style Great House Pueblo. Chimney Rock is the highest in elevation of all the Chacoan sites, at about 7,000 feet above sea level.’

From the Visitor Center, it’s a a 2½ mile drive, on a gravel road, to a parking lot just below the summit of the mesa, and the ruins there. From the parking lot, it’s a steady climb over about a quarter of mile to reach the summit, at 7620 feet.

The panorama there takes in the Rockies to the east, and southwest into New Mexico towards Chaco Canyon, about 90 miles away.

You can view my Chimney Rock photo album here.

Our visits to these extraordinary sites have, for me, generated more questions than answers. I need to spend some time researching human expansion across North America over the millennia. And the story of how agriculture developed in this region of the Four Corners continues to fascinate me.

Over recent weeks, Steph and I have been enjoying the latest series of

Over recent weeks, Steph and I have been enjoying the latest series of

Or the foundations of the

Or the foundations of the