Friday 12 December 1975. Fifty years ago today!

Harold Wilson had almost reached the end of his second term as Prime Minister. Queen were No. 1 in the UK chart with Bohemian Rhapsody, and would remain there for several weeks.

And, at The University of Birmingham, as the clock on Old Joe (actually the Joseph Chamberlain Memorial Clock Tower) struck 12 noon, so the Chancellor’s Procession made its way (to a musical accompaniment played by the University Organist) from the rear of the Great Hall to the stage.

And, at The University of Birmingham, as the clock on Old Joe (actually the Joseph Chamberlain Memorial Clock Tower) struck 12 noon, so the Chancellor’s Procession made its way (to a musical accompaniment played by the University Organist) from the rear of the Great Hall to the stage.

Thus began a degree congregation (aka commencement in US parlance) to confer graduate and undergraduate degrees in the physical sciences (excluding physics and chemistry), biological and medical sciences, and in medicine and dentistry.  All the graduands and their guests remained seated.

All the graduands and their guests remained seated.

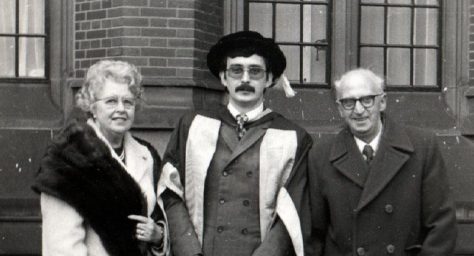

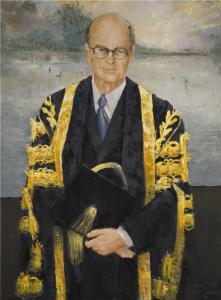

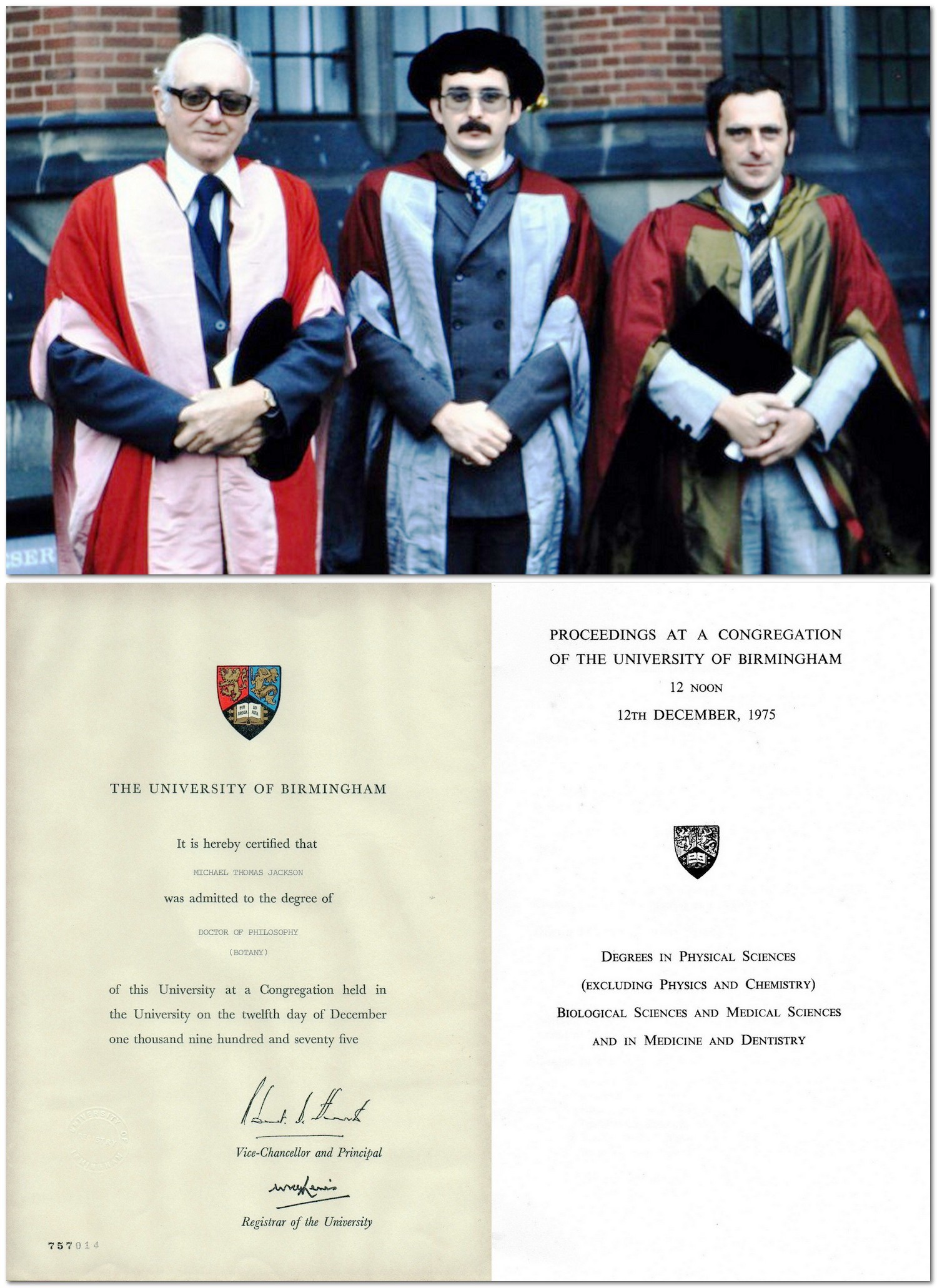

And I was among those graduands, about to have my PhD conferred by the Chancellor and renowned naturalist Sir Peter Scott (right).

Here are some photos taken during the ceremony as I received my degree, in the procession leaving the Great Hall, and with my parents afterwards.

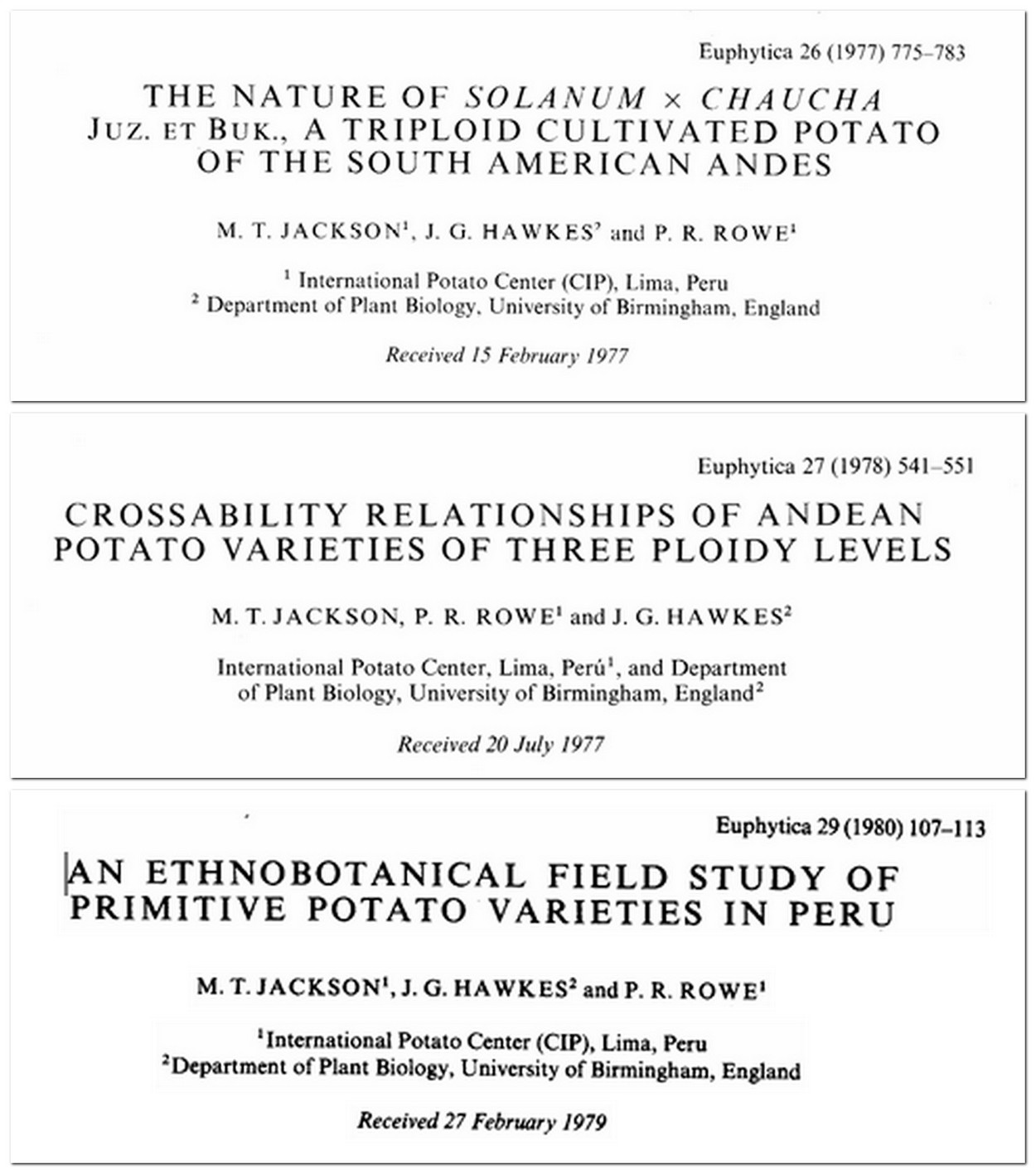

I’d completed my thesis on the biosystematics of South American potatoes, The Evolutionary Significance of the Triploid Cultivated Potato, Solanum x chaucha Juz. et Buk., at the end of September, just meeting the deadline to have the degree conferred (subject to a successful examination) at the December congregation.

Native potato varieties from the Andes of South America.

My thesis defence (an oral examination or viva voce to give its complete title) was held around the third week of October if my memory serves me right. Fortunately I didn’t have to make any significant corrections to the text, and the examiners’ reports were duly submitted and the degree confirmed by the university [1].

Among the university staff who attended the degree congregation were Professor JG ‘Jack’ Hawkes, Mason Professor of Botany and head of the Department of Botany (later Plant Biology) in the School of Biological Sciences, and Dr J Trevor Williams, Course Tutor for the MSc degree course Conservation and Utilisation of Plant Genetic Resources in the same department.

Jack was a world-renowned expert on the taxonomy of potatoes and a pioneer in the field of genetic resources conservation, who founded the MSc course in 1969. He supervised my PhD research. Trevor had supervised my MSc dissertation on lentils, Studies in the Genus Lens Miller with Special Reference to Lens culinaris Medik., in 1971 when I first came to Birmingham to join the plant genetic resources course.

Here I am with Jack (on my right) and Trevor just after the congregation. Click on the image to view an abridged version of the congregation program.

At the same congregation several other graduates from the Department of Botany received their MSc degrees in genetic resources or PhD.

L-R: Pamela Haigh, Brenig Garrett, me, Trevor Williams, Jack Hawkes, Jean Hanson, Margaret Yarwood, Jane Toll, and Stephen Smith

When I began my MSc studies in genetic resources conservation and use at Birmingham in September 1970 I had no clear idea how to forge a career in this fascinating field. The other four students in my cohort came from positions in their own countries, to which they would return after graduating.

My future was much less certain, until one day in February 1971 when Jack Hawkes  returned to Birmingham from an expedition to collect wild potatoes in Bolivia. He told me about a one-year vacancy from September that same year at the International Potato Center (CIP) in Lima, Peru, and asked if I’d be interested. Not half! And as the saying goes, The rest is history.

returned to Birmingham from an expedition to collect wild potatoes in Bolivia. He told me about a one-year vacancy from September that same year at the International Potato Center (CIP) in Lima, Peru, and asked if I’d be interested. Not half! And as the saying goes, The rest is history.

Jack’s expedition had been supported, in part, by CIP’s Director General, Dr Richard Sawyer, who told Jack that he wanted to send a young Peruvian scientist, Zósimo Huaman, to attend the MSc course at Birmingham from September 1971. He was looking for someone to fill that vacancy and did he know of anyone who fitted the bill. Knowing of my interest of working in South America if the opportunity arose, Jack told Sawyer about me. I met him some months later in Birmingham.

Well, things didn’t proceed smoothly, even though Zósimo came to Birmingham as scheduled. Because of funding delays at the UK’s Overseas Development Administration, ODA (which became the Department for International Development or DfID before it was absorbed into the Foreign Office), I wasn’t able to join CIP until January 1973.

In the interim, Jack persuaded ODA to support me at Birmingham until I could move to CIP, and he registered me for a PhD program. He just told me: I think we should work on the triploids. And I was left to my own devices to figure out just what that might mean, searching the literature, growing some plants at Birmingham to get a feel for potatoes, even making a stab (rather unsuccessfully) at learning Spanish.

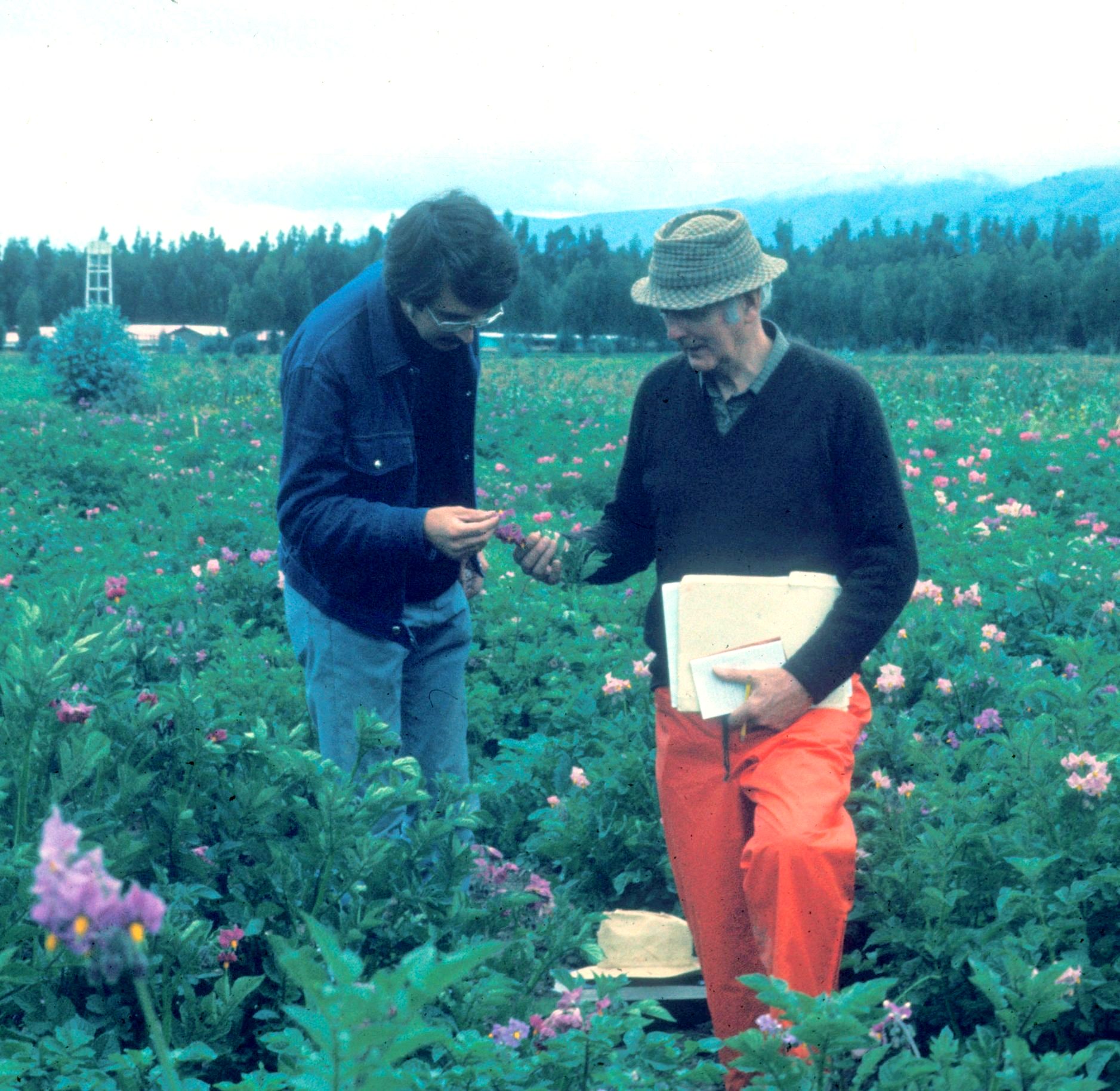

Despite his relaxed view about what my PhD research might encompass, Jack was incredibly supportive, and we spent time in the field together on both occasions he visited CIP while I was there.

With Jack Hawkes in the CIP potato germplasm collection field, in Huancayo, central Peru (alt. 3100 masl) in January 1974.

I was also extremely fortunate that I had, as my local supervisor at CIP, the head of the Department of Breeding & Genetics, Dr P Roger Rowe, originally a maize geneticist, who joined CIP in mid-1973 from the USDA potato collection in Wisconsin where he was the curator. Roger and I have remained friends ever since, and Steph and I met him and his wife Norma in 2023 during our annual visit to the USA (where our elder daughter lives).

Roger and Norma Rowe, Steph and me beside the mighty Mississippi in La Crosse, Wisconsin in June 2023.

On joining CIP, Roger thoroughly evaluated—and approved—my research plans, while I also had some general responsibilities to collect potatoes in Peru, which I have written about in these two posts.

My research involved frequent trips between December and May each year to the CIP field station in Huancayo, to complete a crossing program between potato varieties with different chromosome numbers and evaluating their progeny. In CIP headquarters labs in Lima, I set about describing and classifying different potato varieties, and comparing them using a number of morphological and biochemical criteria. And I made field studies to understand how farmers grow their mixed fields of potato varieties in different regions of Peru.

At the beginning of April 1975, Steph and I returned to Birmingham so that I could write my thesis. But we didn’t fly directly home. Richard Sawyer had promised me a postdoctoral position with CIP—subject to successful completion of my PhD—with a posting in the Outreach Program (then to become the Regional Research and Training Program) based in Central America. So we spent time visiting Costa Rica and Mexico before heading for New York and a flight back to Manchester. And all the while keeping a very close eye on my briefcase that contained all my raw research data. Had that gone astray I’m not sure what I would have done. No such thing in 1975 as personal computers, cloud storage and the like. So, you can imagine my relief when we eventually settled into life again in Birmingham, and I could get on with the task in hand: writing my thesis and submitting it before the 1 October deadline.

I still had some small activities to complete, and I didn’t start drafting my thesis in earnest until July. It took me just six weeks to write, and then I spent time during September preparing all the figures. Jack’s technician, Dave Langley, typed my thesis on a manual typewriter!

Of course each chapter had to be approved by Jack. And he insisted that I handed over each chapter complete, with the promise that he’d read it that same evening and return the draft to me with corrections and suggestions by the next day, or a couple of days at most. That was a supervision model I took on board when I became a university lecturer in 1981 and had graduate students of my own.

Looking back, my thesis was no great shakes. It was, I believe, a competent piece of research that met the university criteria for the award of a PhD: that it should comprise original research carried out under supervision, and of a publishable standard.

I did publish three papers from my thesis, which have been cited consistently in the scientific literature over the years by other researchers.

So, PhD under my belt so-to-speak, Steph and I returned to Lima just before New Year 1976. Later in April that year, we moved to Costa Rica where I did research on a serious bacterial disease of potatoes, seed potato production, and co-founded a pioneer regional cooperative program on potato research and development. We remained in Costa Rica for almost five years before returning to Lima, and from there to The University of Birmingham.

I taught at Birmingham for a decade before becoming Head of the Genetic Resources Center (with the world’s largest and most important rice genebank) at the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in Los Baños, Philippines from July 1991. Then in May 2001, I gave up any direct involvement in research and joined IRRI’s senior management team as Director for Program Planning and Communications. I retired in 2010 and returned to the UK.

50 years later

Since retiring, I’ve co-edited—in 2013—a major text on climate change and genetic resources, and led an important review, in 2016-2017, of the management of a network of international genebanks.

Without a PhD none of this would have been possible. Indeed continued employment at CIP in 1976 was contingent upon successful completion of my PhD.

I was extremely fortunate that, as a graduate student (from MSc to PhD) I had excellent mentors: Trevor, Jack, and Roger. I learned much from them and throughout my career tried (successfully I hope) to emulate their approach with my colleagues, staff who reported to me, and students. I’ve also held to the idea that one is never too old to have mentors.

[1] I completed my PhD in four years (September 1971 to September 1975. Back in the day, PhD candidates were allowed eight years from first registration to carry out their research and submit their thesis for examination. Because of concern about submission rates among PhD students in the 1980s, The University of Birmingham (and other universities) reduced the time limit to five years then to four. So nowadays, a PhD program in the UK comprises three years of research plus one year to write and submit the thesis, to be counted as an on-time submission.

The route south on US61 and US14 follows the river, and you’re never very far from it. In several places the Mississippi opens out into large lakes before continuing its flow south to the Gulf of Mexico. And it was while we were driving along that I realised just how close to the river the railroad line was built, and which we experienced in 2015 on

The route south on US61 and US14 follows the river, and you’re never very far from it. In several places the Mississippi opens out into large lakes before continuing its flow south to the Gulf of Mexico. And it was while we were driving along that I realised just how close to the river the railroad line was built, and which we experienced in 2015 on

Philosophiae Doctor. Doctor of Philosophy. PhD. Or DPhil in some universities like Oxford. Doctorate. Hard work. Long-term benefits.

Philosophiae Doctor. Doctor of Philosophy. PhD. Or DPhil in some universities like Oxford. Doctorate. Hard work. Long-term benefits. Although registered for my PhD at the University of Birmingham, I actually carried out much of the research while working as an Associate Taxonomist at the

Although registered for my PhD at the University of Birmingham, I actually carried out much of the research while working as an Associate Taxonomist at the