Potatoes were not my first choice

Hindsight is a wonderful thing. Although I spent more than 20 years studying potatoes – in a variety of guises – that had not been my first choice. I originally wanted to become the world’s lentil expert.

Hindsight is a wonderful thing. Although I spent more than 20 years studying potatoes – in a variety of guises – that had not been my first choice. I originally wanted to become the world’s lentil expert.

Well, not exactly. When I joined the 1970 intake on the MSc course Conservation and Utilization of Plant Genetic Resources at the University of Birmingham, I quickly decided to work with Trevor Williams on the taxonomy and origin of lentils (Lens culinaris). I wanted to study variation in a crop species that had received little attention; and preferably it had to be a legume species.

Working our way through Flora Europaea, we came across the notation under lentil: Origin unknown. Now that seemed like an interesting challenge, and we began to plan a suitable dissertation project on that basis. I completed my dissertation in September 1971.

Daniel Zohary

Interestingly, unknown to Trevor and me, renowned Israeli expert on crop evolution Professor Daniel Zohary (of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem) had been working on the same problem, and published his results in Economic Botany in 1972 [1], which essentially confirmed the conclusions I’d reached a year earlier.

As it turned out – and this is the hindsight bit – continuing work on lentils was not really an option; and funding for a lentil PhD would have been very difficult to find.

In any case, the MSc course leader Professor Jack Hawkes had, by March 1971, already raised the possibility of spending a year in Peru (see my posts about potatoes in Peru and about Peru in general), which I jumped at. So in January 1973, I landed in Lima, an employee of the recently-founded International Potato Center (CIP).

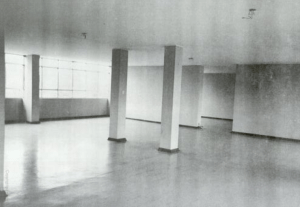

The original CIP building in 1973

First impressions

Then, CIP was housed in just a single building on a developing campus in La Molina, on the eastern outskirts of Lima, where the National Agrarian University is located (in fact, just across the road from CIP). In those days, the journey to La Molina from the Lima suburbs of San Isidro or Miraflores (we lived in Miraflores on Av. Larco, close to the cliffs overlooking the Pacific Ocean) took about 20 minutes. Around La Molina it was essentially a rural setting. But even in those days, housing developments were already underway, and today what were once fields of maize are now ‘fields of concrete’. I’m told that the journey can now take forever, and CIP staff often plan to arrive early or depart late just to avoid the horrendous traffic.

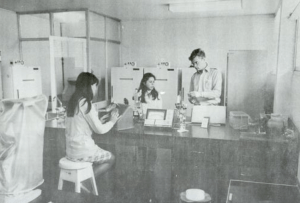

The first floor of the original CIP building

But I digress. The CIP building was essentially an empty shell on both floors. This was gradually partitioned to form offices and laboratories, and over the years, new buildings were added. On my first day at CIP (Friday 5 January) I was shown to my ‘office’ on the upper (first) floor. The whole floor at that time was completely open plan from one end to the other, except for one room opposite the staircase that actually had two solid walls either side (the toilets were located on either side), and a wooden panel front. Inside was a desk, a chair, a filing cabinet, and a bookshelf. That was it!

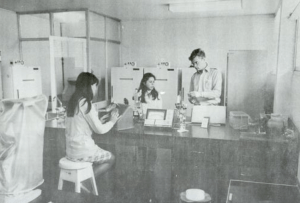

John Vessey (British plant pathologist working on bacterial wilt) and Rosa Mendez in the plant pathology laboratory of the national agricultural research institute close-by CIP. I’m not sure who has her back to the camera – it might be Liliam Lindo de Gutarra

While there were no laboratories as such at CIP until a few months later (the pathologists were using space in a national program laboratory building across the street), we did have access to a couple of screenhouses at La Molina for growing experimental materials, but that was quite a challenge in the heat of the Lima summer from January to April until facilities with some sort of cooling system were constructed.

I must admit I did wonder what I’d let myself in for. There were no established research facilities such as laboratories, I didn’t speak Spanish (although that was rectified in about six months), and went through all the stages of ‘culture shock’.

Carlos Ochoa – renowned Peruvian potato taxonomist

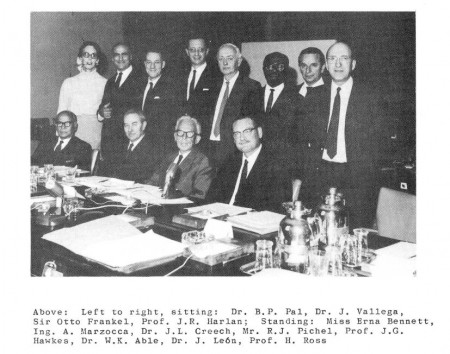

A planning meeting on germplasm

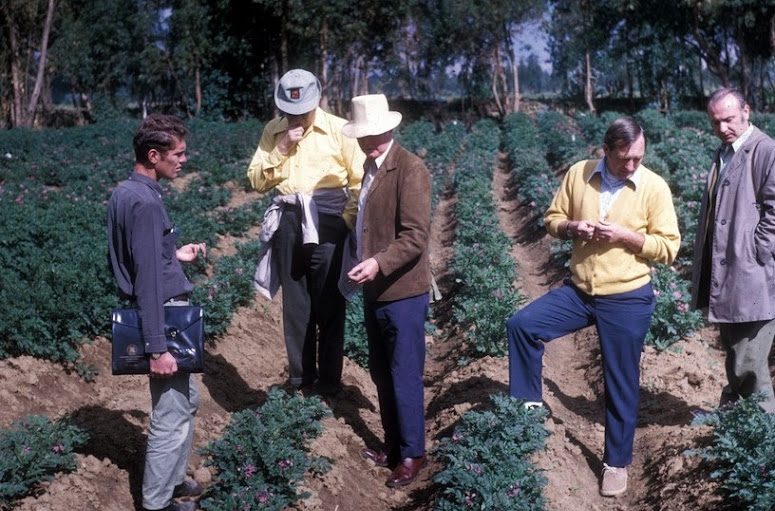

The following week CIP held the second planning workshop (but the first on germplasm and taxonomy) of a whole series that would be convened over the next decade to help plan its program. The participants were Jack Hawkes, taxonomist Carlos Ochoa (Peru), potato breeder Frank Haynes (North Carolina State University), geneticist Roger Rowe (then with the USDA regional potato germplasm project in Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin, and later to join CIP in July 1973 as head of the breeding and genetics department), ethnobotanist and taxonomist Don Ugent (Southern Illinois University-Carbondale), and potato breeder Richard Tarn (from Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, New Brunswick, and a former PhD student of Jack Hawkes), and myself. We made a trip to Huancayo in the central Andes (more than 3000 m above sea level) where CIP proposed to establish its highland field station (more of that below), and also to Cuzco in southern Peru (where I seized the opportunity, with Richard Tarn, of making a day trip to Machu Picchu). In Huancayo, we visited the small, but growing, potato germplasm collection which in those days was being multiplied on rented land.

L to r: David Baumann, Frank Haynes, Jack Hawkes, Roger Rowe, Don Ugent

The field supervisor was a young agronomist, David Baumann, who can be seen in this photo explaining the collection to the workshop participants. Around this time, plant pathologist Dr Marco Soto – who had just returned from his PhD studies in the USA – was named as the head of the Huancayo station.

The arrangements for that meeting say a lot about the early CIP days. We traveled to Huancayo by road, in two Iranian-built Hillman station wagons, one of them driven by the CIP Director General, Richard Sawyer. Another point worth mentioning is the research planning strategy that CIP implemented. Since potato research was strong in many countries around the world, Sawyer decided it would be effective to engage potato scientists from elsewhere in CIP’s research. Not only were they invited to participate in planning workshops, they also received research grants to carry out specific research projects (such as the potato breeding and nematology resistance research at Cornell University, for example), and provide graduate opportunities for students sponsored by CIP. This approach, as well as developing a regional program for research and dissemination, were heavily criticised in the early days of the CGIAR. This was not the approach taken by other centers such as IRRI, CIMMYT, and CIAT for example. It now seems a rather silly opposition, and is more the norm than the exception in how the centers of the CGIAR do business.

The arrangements for that meeting say a lot about the early CIP days. We traveled to Huancayo by road, in two Iranian-built Hillman station wagons, one of them driven by the CIP Director General, Richard Sawyer. Another point worth mentioning is the research planning strategy that CIP implemented. Since potato research was strong in many countries around the world, Sawyer decided it would be effective to engage potato scientists from elsewhere in CIP’s research. Not only were they invited to participate in planning workshops, they also received research grants to carry out specific research projects (such as the potato breeding and nematology resistance research at Cornell University, for example), and provide graduate opportunities for students sponsored by CIP. This approach, as well as developing a regional program for research and dissemination, were heavily criticised in the early days of the CGIAR. This was not the approach taken by other centers such as IRRI, CIMMYT, and CIAT for example. It now seems a rather silly opposition, and is more the norm than the exception in how the centers of the CGIAR do business.

So who worked at CIP in the early days?

In Lima, there were only a handful of staff in January 1973, me included as a Fellow in Taxonomy, even though I only had a masters degree, and would continue with my PhD research while working for CIP.

L to r: Ed French, Richard Sawyer, John Vessey, secretary (Lupe?), Rosa Benavides, Carlos Bohl, Haydee de Zelaya, Rosa Mendez, Heather (secretary to the DG), Oscar Gil, Javier Franco, Luis Salazar, David Baumann. Not all staff are shown.

Head of plant pathology, and long-time North Carolina team member, Ed French (a US citizen of Anglo-Argentinian ancestry) had already begun to recruit staff. Post-doctoral fellow John Vessey from the UK worked on resistance to bacterial wilt, and he and his wife Marian became close friends (we are still in touch with them), although John departed for CIMMYT in Mexico in 1974, followed by United Fruit in Honduras – more bacterial wilt – before returning to the UK (John was my principal contact for the somaclone project I reported in another post).

Rainer Zachmann

At first, there were few internationally-recruited staff, but throughout 1973, the staff increased quite rapidly. Rainer Zachmann, a German plant pathologist working on Rhizoctonia solani, joined in February, followed by Julia Guzman, a late blight specialist from Colombia; Parviz Jatala, a nematologist from Iran; Ray Meyer, an agronomist from the USA; and Dick Wurster as head of the Outreach Dept. , among others. Dick had been working in Uganda prior to joining CIP.

Dick Wurster

A qualified pilot, Dick brought his plane with him (it had two engines – one at the front, and one behind!), which was also used by CIP to ferry staff to Huancayo on occasion, although we usually made the six hour journey by road. Jim Bryan returned from his leave in the USA to join CIP as a seed specialist.

Among the Peruvian staff were virologist Luis Salazar (who gained his PhD some years later from the University of Dundee in Scotland), nematologist Javier Franco (who studied at Rothamsted for a University of London PhD), and plant pathologist Oscar Hidalgo (who went to North Carolina State University). Just returned from Cornell was Dr Marco Soto (a plant pathologist) who became superintendent of the Huancayo experiment station. About to return from graduate studies overseas were plant physiologists Willy Roca (and his wife Charo) and Fernando Ezeta, and virologist Anna-Maria Hinostroza. Nematologist Maria Scurrah (who was born in Huancayo of German parents, and who spoke Spanish, German and English will equal rapidity) returned from her PhD studies at Cornell in 1972. Entomologist Luis Valencia was mentored by Maurie Semel who was on sabbatical from Cornell. Zosimo Huaman returned from Birmingham in April 1973.

The first support staff included secretaries Rosa Benavides (who sadly succumbed to cancer just a few years later) and Haydee de Zelaya, caretaker José Machuca, messenger Victor Madrid (who eventually became a very talented member of the communications support team), carpenter Maestro Caycho, and screenhouse technicians, the Gomez brothers – Lauro, Felix, and Walter.

Municipalidad de Miraflores – where we married in October 1973

My fiancée Stephanie joined me in Lima in July 1973 and began work as a germplasm expert with the CIP potato collection. We married in October 1973 in the Municipalidad de Miraflores, near to where we were renting a 12th floor apartment on Av. Larco.

[1] Zohary, D. 1972. The wild progenitor and the place of origin of the cultivated lentil: Lens culinaris. Economic Botany 26: 326-332.

I could imagine a program on potatoes, for example, that would take the viewer to the Andes of Peru, looking at indigenous potato cultivation, linking it to the origins of Inca agriculture and the archaeology of the coastal cultures, the wealth of diversity of more than 200 wild species in the Americas, how these are conserved in major genebank collections in the USA and Europe (as well as at the International Potato Center in Lima), and how this diversity is used in potato breeding. No longer would we take these crops for granted! And the same could be done for wheat and barley – the cereal staples of the Middle east, with its wealth of archaeology in Turkey, Syria and Iraq, maize in Mexico and coastal Peru, and many other examples.

I could imagine a program on potatoes, for example, that would take the viewer to the Andes of Peru, looking at indigenous potato cultivation, linking it to the origins of Inca agriculture and the archaeology of the coastal cultures, the wealth of diversity of more than 200 wild species in the Americas, how these are conserved in major genebank collections in the USA and Europe (as well as at the International Potato Center in Lima), and how this diversity is used in potato breeding. No longer would we take these crops for granted! And the same could be done for wheat and barley – the cereal staples of the Middle east, with its wealth of archaeology in Turkey, Syria and Iraq, maize in Mexico and coastal Peru, and many other examples.

Hindsight is a wonderful thing. Although I spent more than 20 years studying potatoes – in a variety of guises – that had not been my first choice. I originally wanted to become the world’s lentil expert.

Hindsight is a wonderful thing. Although I spent more than 20 years studying potatoes – in a variety of guises – that had not been my first choice. I originally wanted to become the world’s lentil expert.

The arrangements for that meeting say a lot about the early CIP days. We traveled to Huancayo by road, in two Iranian-built Hillman station wagons, one of them driven by the CIP Director General, Richard Sawyer. Another point worth mentioning is the research planning strategy that CIP implemented. Since potato research was strong in many countries around the world, Sawyer decided it would be effective to engage potato scientists from elsewhere in CIP’s research. Not only were they invited to participate in planning workshops, they also received research grants to carry out specific research projects (such as the potato breeding and nematology resistance research at Cornell University, for example), and provide graduate opportunities for students sponsored by CIP. This approach, as well as developing a regional program for research and dissemination, were heavily criticised in the early days of the CGIAR. This was not the approach taken by other centers such as

The arrangements for that meeting say a lot about the early CIP days. We traveled to Huancayo by road, in two Iranian-built Hillman station wagons, one of them driven by the CIP Director General, Richard Sawyer. Another point worth mentioning is the research planning strategy that CIP implemented. Since potato research was strong in many countries around the world, Sawyer decided it would be effective to engage potato scientists from elsewhere in CIP’s research. Not only were they invited to participate in planning workshops, they also received research grants to carry out specific research projects (such as the potato breeding and nematology resistance research at Cornell University, for example), and provide graduate opportunities for students sponsored by CIP. This approach, as well as developing a regional program for research and dissemination, were heavily criticised in the early days of the CGIAR. This was not the approach taken by other centers such as

When the late

When the late

Here is the list of University of Birmingham PhD students who worked on potatoes, as far as I can remember. All of them from 1975 (with the exception of Ian Gubb) had also attended the MSc course on genetic resources:

Here is the list of University of Birmingham PhD students who worked on potatoes, as far as I can remember. All of them from 1975 (with the exception of Ian Gubb) had also attended the MSc course on genetic resources: Richard Lester (UK), 1962. Taught at Makerere University in Uganda, before joining the Dept. of Botany at Birmingham in 1969. Retired in 2002, and died in 2006. Studied the biochemical systematics of Mexican wild Solanum species. The species Solanum lesteri is named after him.

Richard Lester (UK), 1962. Taught at Makerere University in Uganda, before joining the Dept. of Botany at Birmingham in 1969. Retired in 2002, and died in 2006. Studied the biochemical systematics of Mexican wild Solanum species. The species Solanum lesteri is named after him.

Katsuo Armando Okada (Argentina), 1970 (?). Retired. Was with IBPGR for a while in the 1980s (?) in Colombia. Studied the origin of Solanum x rechei from Argentina.

Katsuo Armando Okada (Argentina), 1970 (?). Retired. Was with IBPGR for a while in the 1980s (?) in Colombia. Studied the origin of Solanum x rechei from Argentina.

David Astley (UK), 1975. Became the curator of the vegetable genebank at Wellesbourne (now the

David Astley (UK), 1975. Became the curator of the vegetable genebank at Wellesbourne (now the

Peter Schmiediche (Germany), 1977. He continued working with CIP as a potato breeder (for resistance to bacterial wilt), and was later CIP’s regional leader based in Indonesia. Now retired and sharing his time between Texas (where his children settled) and his native Berlin. Studied the bitter potatoes Solanum x juzepczukii (3x) and S. x curtilobum (5x). Joint with CIP and Roger Rowe.

Peter Schmiediche (Germany), 1977. He continued working with CIP as a potato breeder (for resistance to bacterial wilt), and was later CIP’s regional leader based in Indonesia. Now retired and sharing his time between Texas (where his children settled) and his native Berlin. Studied the bitter potatoes Solanum x juzepczukii (3x) and S. x curtilobum (5x). Joint with CIP and Roger Rowe. Carlos Arbizu (Peru), 1990. An expert on minor Andean tuber crops, he came from the University of Ayacucho. Spent time working in the germplasm program at CIP. Studied the origin and value of resistance to spindle tuber viroid in Solanum acaule. Joint with CIP and principal virologist Luis Salazar (who gained his PhD while studying at the

Carlos Arbizu (Peru), 1990. An expert on minor Andean tuber crops, he came from the University of Ayacucho. Spent time working in the germplasm program at CIP. Studied the origin and value of resistance to spindle tuber viroid in Solanum acaule. Joint with CIP and principal virologist Luis Salazar (who gained his PhD while studying at the  Susan Juned (UK), 1994. Now a sustainable technology consultant, Sue is an active local government councillor, and has stood for election to parliament on a couple of occasions for the Liberal Democrats. Studied

Susan Juned (UK), 1994. Now a sustainable technology consultant, Sue is an active local government councillor, and has stood for election to parliament on a couple of occasions for the Liberal Democrats. Studied  David Tay (Malaysia), 2000. He worked in Australia and then was Director of the USDA Ornamental Plant Germplasm Center in Columbus, Ohio, but returned to CIP as head of the genetic resources unit in 2007. He’s now left CIP. I think he worked on diploid cultivated species. Joint with CIP. Not sure why his PhD is dated 2000, as he’d been in CIP in the late 70s.

David Tay (Malaysia), 2000. He worked in Australia and then was Director of the USDA Ornamental Plant Germplasm Center in Columbus, Ohio, but returned to CIP as head of the genetic resources unit in 2007. He’s now left CIP. I think he worked on diploid cultivated species. Joint with CIP. Not sure why his PhD is dated 2000, as he’d been in CIP in the late 70s.

Roger Rowe, who had been in charge of the

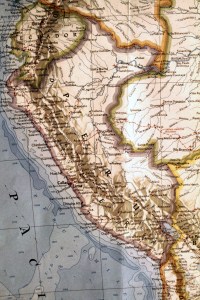

Roger Rowe, who had been in charge of the  I can’t remember why I had always wanted to visit Peru. All I know is that since I was a small boy, Peru had held a big fascination for me. I used to spend time leafing through an atlas, and spending most time looking at the maps of South America, especially Peru. And I promised myself (in the way that you do when you’re small, and can’t see how it would ever happen) that one day I would visit Peru.

I can’t remember why I had always wanted to visit Peru. All I know is that since I was a small boy, Peru had held a big fascination for me. I used to spend time leafing through an atlas, and spending most time looking at the maps of South America, especially Peru. And I promised myself (in the way that you do when you’re small, and can’t see how it would ever happen) that one day I would visit Peru. To cut a long story short, I didn’t go in 1971, but landed in Lima at the beginning of January 1973 after a long and gruelling flight on B.O.A.C. from London via Antigua (in the Caribbean), Caracas, and Bogotá.

To cut a long story short, I didn’t go in 1971, but landed in Lima at the beginning of January 1973 after a long and gruelling flight on B.O.A.C. from London via Antigua (in the Caribbean), Caracas, and Bogotá.

In early 1974 I travelled to southern Peru with a taxonomist friend from the University of St Andrews, Dr Peter Gibbs (right).

In early 1974 I travelled to southern Peru with a taxonomist friend from the University of St Andrews, Dr Peter Gibbs (right).

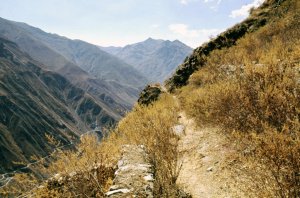

The drive south in a small Land Rover – down the coastal desert Panamericana highway, across the Nasca plain, climbing to Arequipa, and even higher to Puno – took three days. After resting up in Puno (next to Lake Titicaca), and getting used to the 3827 m altitude, we set off for Cuyo Cuyo. Dropping down from the altiplano at well over 4000 m, Cuyo Cuyo lies at an altitude of about 3300 m. Below the village the valley drops quickly towards the ceja de la montaña – literally ‘eyebrow of the mountain’ – where the humid air of the rainforests below rises up east-facing valleys to form cloud forest.

The drive south in a small Land Rover – down the coastal desert Panamericana highway, across the Nasca plain, climbing to Arequipa, and even higher to Puno – took three days. After resting up in Puno (next to Lake Titicaca), and getting used to the 3827 m altitude, we set off for Cuyo Cuyo. Dropping down from the altiplano at well over 4000 m, Cuyo Cuyo lies at an altitude of about 3300 m. Below the village the valley drops quickly towards the ceja de la montaña – literally ‘eyebrow of the mountain’ – where the humid air of the rainforests below rises up east-facing valleys to form cloud forest.

Peter and I set up camp, so-to-speak, in the local post office where we could sleep, brew the odd cup of tea (there was a small café in the village where we could eat), and gather our specimens together, including a rudimentary drier for the extensive set of oca herbarium samples that Peter intended to make. But more of that particular story later.

Peter and I set up camp, so-to-speak, in the local post office where we could sleep, brew the odd cup of tea (there was a small café in the village where we could eat), and gather our specimens together, including a rudimentary drier for the extensive set of oca herbarium samples that Peter intended to make. But more of that particular story later. The sides of the Cuyo Cuyo valley are covered with the most wonderful system of agricultural terraces, called andenes, which must have been constructed centuries ago, in Inca times, and have been cultivated ever since. Farmers have different terraces dotted around the valley, and when I was there, at least, farmers were still using a communal rotation system. Thus in one part of the valley the terraces were covered in potatoes (year 1 after a fallow), and oca (years 2 and 3), barley or beans (year 4), or fallow (years 5-8) elsewhere. Sheep are corralled on a terrace prior to planting potatoes, and their urine and dung used as fertilizer. Whether, almost 40 years later, this remains the case I do not know.

The sides of the Cuyo Cuyo valley are covered with the most wonderful system of agricultural terraces, called andenes, which must have been constructed centuries ago, in Inca times, and have been cultivated ever since. Farmers have different terraces dotted around the valley, and when I was there, at least, farmers were still using a communal rotation system. Thus in one part of the valley the terraces were covered in potatoes (year 1 after a fallow), and oca (years 2 and 3), barley or beans (year 4), or fallow (years 5-8) elsewhere. Sheep are corralled on a terrace prior to planting potatoes, and their urine and dung used as fertilizer. Whether, almost 40 years later, this remains the case I do not know.

The Andes of South America are the home of the potato that has supported indigenous civilizations for thousands of years. As many as 4,000 native potato varieties are still grown. The region around Lake Titicaca in southern Peru and northern Bolivia is particularly rich in genetic diversity, and the wild potatoes from here are valuable for their disease and pest resistance [1].

The Andes of South America are the home of the potato that has supported indigenous civilizations for thousands of years. As many as 4,000 native potato varieties are still grown. The region around Lake Titicaca in southern Peru and northern Bolivia is particularly rich in genetic diversity, and the wild potatoes from here are valuable for their disease and pest resistance [1]. I joined CIP in January 1973 as Associate Taxonomist, charged with the task of collecting potato varieties and helping them to maintain the large germplasm collection, that grew to at least 15,000 separate entries (or clonal accessions), but was reduced to a more manageable number through the elimination of duplicate samples. The germplasm collection was planted each year from October through April, coinciding with the most abundant rains, in the field in Huancayo, central Peru at an altitude of more than 3,100 meters.

I joined CIP in January 1973 as Associate Taxonomist, charged with the task of collecting potato varieties and helping them to maintain the large germplasm collection, that grew to at least 15,000 separate entries (or clonal accessions), but was reduced to a more manageable number through the elimination of duplicate samples. The germplasm collection was planted each year from October through April, coinciding with the most abundant rains, in the field in Huancayo, central Peru at an altitude of more than 3,100 meters.

that endeavour. In May 1973 I joined my colleague Zosimo Huaman (left) to collect potatoes in the Departments of Ancash and La Libertad, to the north of Lima. The highest mountains in Peru are found in Ancash, and our route took us through into the

that endeavour. In May 1973 I joined my colleague Zosimo Huaman (left) to collect potatoes in the Departments of Ancash and La Libertad, to the north of Lima. The highest mountains in Peru are found in Ancash, and our route took us through into the

of a minor Andean tuber crop called oca (Oxalis tuberosa). We went to the village of Cuyo Cuyo, more than 100 km north of Puno in southern Peru. Dropping down from the altiplano, the road hugs the sides of the valley, and is often blocked by landslides (a very common occurrence throughout Peru in the rainy season). Along the way – and due to the warmer air rising from the selva (jungle) to the east – the vegetation is quite luxurious in places, as the white begonia below shows (the flowers were about 8 cm in diameter). Eventually the valley opens out, with terraces on all sides. These terraces (or andenes) are ancient structures constructed by the Incas to make the valley more productive.

of a minor Andean tuber crop called oca (Oxalis tuberosa). We went to the village of Cuyo Cuyo, more than 100 km north of Puno in southern Peru. Dropping down from the altiplano, the road hugs the sides of the valley, and is often blocked by landslides (a very common occurrence throughout Peru in the rainy season). Along the way – and due to the warmer air rising from the selva (jungle) to the east – the vegetation is quite luxurious in places, as the white begonia below shows (the flowers were about 8 cm in diameter). Eventually the valley opens out, with terraces on all sides. These terraces (or andenes) are ancient structures constructed by the Incas to make the valley more productive.

John Gregory ‘Jack’ Hawkes – botanist, educator, and visionary – was born in Bristol in 1915. After completing his secondary education at Cheltenham Grammar School in 1934, he won a place at Christ’s College, University of Cambridge, graduating with a BA (Natural Sciences, first class honours) in 1937. His MA was awarded in 1938, and he completed his PhD in 1941 under the supervision of the noted potato breeder and historian, Dr Redcliffe N Salaman FRS. The university awarded Jack the ScD degree in 1957.

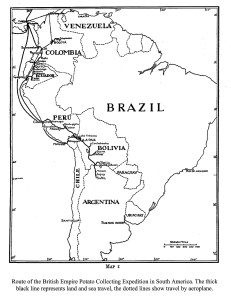

John Gregory ‘Jack’ Hawkes – botanist, educator, and visionary – was born in Bristol in 1915. After completing his secondary education at Cheltenham Grammar School in 1934, he won a place at Christ’s College, University of Cambridge, graduating with a BA (Natural Sciences, first class honours) in 1937. His MA was awarded in 1938, and he completed his PhD in 1941 under the supervision of the noted potato breeder and historian, Dr Redcliffe N Salaman FRS. The university awarded Jack the ScD degree in 1957. On graduation in 1937 Jack successfully applied for the position of assistant to Dr PS Hudson, Director of the Imperial Bureau of Plant Breeding and Genetics in Cambridge, for an expedition to Lake Titicaca in the South American Andes. In the event this expedition did not materialize due to Hudson’s poor health, but a more comprehensive expedition was then planned for 1939, led by EK Balls, a professional plant collector. Thus began Jack’s lifelong interest in ‘the humble spud’.

On graduation in 1937 Jack successfully applied for the position of assistant to Dr PS Hudson, Director of the Imperial Bureau of Plant Breeding and Genetics in Cambridge, for an expedition to Lake Titicaca in the South American Andes. In the event this expedition did not materialize due to Hudson’s poor health, but a more comprehensive expedition was then planned for 1939, led by EK Balls, a professional plant collector. Thus began Jack’s lifelong interest in ‘the humble spud’.

In addition to his lifelong research on potatoes, Jack also spearheaded scientific interest in the Solanaceae plant family that also includes tomato, tobacco, chili peppers, and eggplant, and many species with pharmaceutical properties. With colleagues at Birmingham in the late 1950s he developed serological methods to study relationships between potato species. He was also one of the leading lights to produce a computer-mapped Flora of Warwickshire, a first of its kind, published in 1971.

In addition to his lifelong research on potatoes, Jack also spearheaded scientific interest in the Solanaceae plant family that also includes tomato, tobacco, chili peppers, and eggplant, and many species with pharmaceutical properties. With colleagues at Birmingham in the late 1950s he developed serological methods to study relationships between potato species. He was also one of the leading lights to produce a computer-mapped Flora of Warwickshire, a first of its kind, published in 1971.