The University of Birmingham, a major English university, received its royal charter in 1900, although a predecessor medical college was founded in Birmingham in 1825.

The University of Birmingham, a major English university, received its royal charter in 1900, although a predecessor medical college was founded in Birmingham in 1825.

Kenneth Mather FRS

Although strong in the various biological sciences – with leading botany, zoology, microbiology, and genetics departments (now combined into a School of Biosciences), Birmingham never had an agriculture faculty. Yet its impact on agriculture worldwide has been significant.

For decades it had one of the strongest genetics departments in the world, with luminaries such as Professor Sir Kenneth Mather FRS* and Professor John Jinks FRS**, leading the way in cytology, and population and quantitative genetics.

John Jinks FRS

In fact, genetics at Birmingham was renowned for its focus on quantitative genetics and applications to plant breeding. For many years it ran a one-year MSc course in Applied Genetics.

The head of the department of botany and Mason Professor of Botany during the 1960s was Jack Heslop-Harrison FRS*** whose research and reviews on genecology would make such valuable contributions to the field of plant genetics resources.

Jack Hawkes

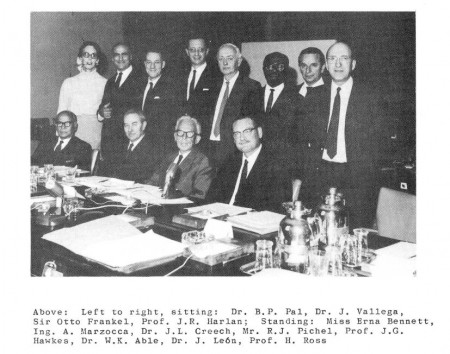

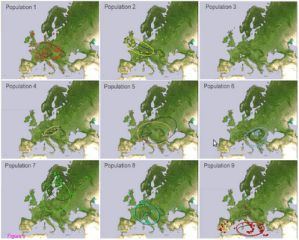

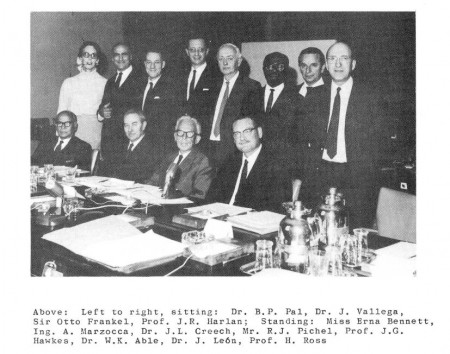

Professor Jack Hawkes OBE succeeded Heslop-Harrison as Mason Professor of Botany in 1967, although he’d been in the department since 1952. Jack was a leading taxonomist of the tuber-bearings Solanums – potatoes! Since 1938 he had made several collecting expeditions to the Americas (often with his Danish colleague JP Hjerting) to collect and study wild potatoes. And it was through his work on potatoes that Jack became involved with the newly-founded plant genetic resources movement under the leadership of Sir Otto Frankel. Jack joined a Panel of Experts at FAO, and through the work of that committee plans were laid at the end of the 1960s to collect and conserve the diversity of crop plants and their wild relatives worldwide, and establish an international network of genebanks.

FAO Panel of Experts, 1960s

The culmination of that initiative – four decades later – was the opening in 2008 of the Svalbard Global Seed Vault.

Jack wondered how a university might contribute effectively to the various genetic resources initiatives, and decided that a one-year training course leading to a masters degree (MSc) would be the best approach. With support from the university, the course on Conservation and Utilization of Plant Genetic Resources took its first intake of four students (from Australia, Brazil, Candada, and the UK) in September 1969. I joined the course in September 1970, alongside Ayla Sencer from Izmir, Turkey, Altaf Rao from Pakistan, Folu Dania Ogbe from Nigeria, and Felix Taborda-Romero from Venezuela. Jack invited many of the people he worked with worldwide in genetic resources to come to Birmingham to give guest lectures. And we were treated to several sessions with the likes of Dr Erna Bennett from FAO and Professor Jack Harlan from the University of Illinois.

From the outset, Frankel thought within 20 years everyone who needed training would have passed through the course. He was mistaken by about 20 years. The course remained the only formal training course of its kind in the world, and by 2008 had trained over 1400 MSc and 3-month short course students from more than 100 countries, many becoming genetic conservation leaders in their own countries. Although the course, as such, is no longer offered, the School of Biosciences still offers PhD opportunities related to the conservation, evaluation and use of genetic resources.

The first external examiner (for the first three years) was Professor Hugh Bunting, Professor of Agricultural Botany at the University of Reading. Other examiners over the years have included Professor Eric Roberts (Reading) and Professor John Cooper FRS (Aberystwyth) and directors of Kew, Professor Sir Arthur Bell and Professor Sir Peter Crane FRS. Students were also able to carry out their dissertation research over the years at other institutions, such as Kew-Wakehurst Place (home of the Millennium Seed Bank) and the Genetic Resources Unit, Warwick Crop Centre (formerly the National Vegetable Genebank at Wellesbourne) where the manager for many years was Dr Dave Astley, a Birmingham graduate from the 1971 intake.

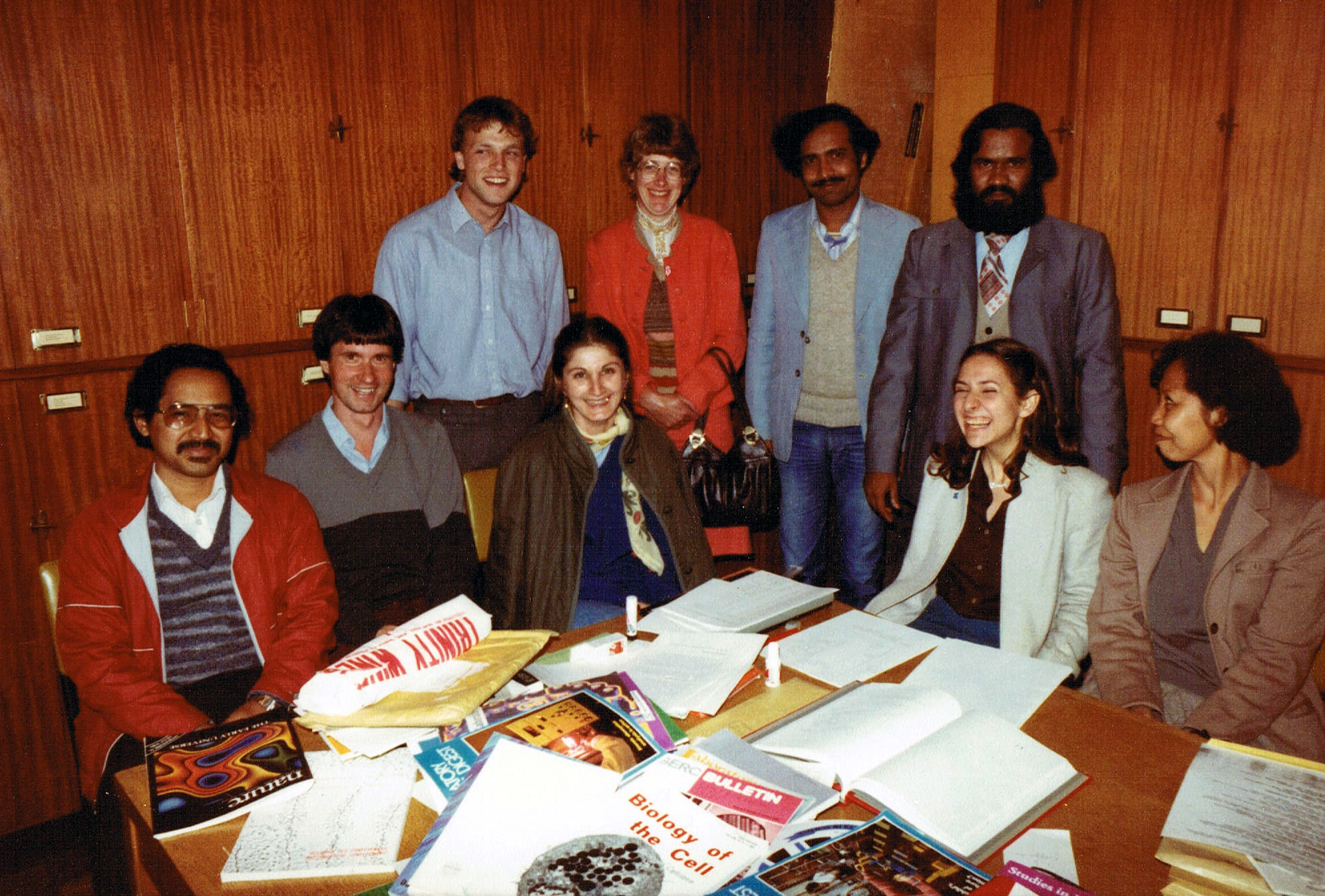

And what has been the impact of training so many people? Most students returned to their countries and began work in research – collecting and conserving. In 1996, FAO presented a report, The State of the World’s Plant Genetic Resources, to the Fourth International Technical Conference on Plant Genetic Resources held in Leipzig, Germany, in June 1996, and published in 1998. Many Birmingham graduates attended that conference as members of national delegations, and some even headed their delegations. In the photo below, everyone is a Birmingham graduate, with the exception of Dr Geoff Hawtin, Director General (fourth from the right, at the back) and Dr Lyndsey Withers, Tissue Culture Specialist (seventh from the right, front row) from IPGRI (now Bioversity International) that provided scholarships to students from developing countries, and guest lectures. Two other delegates, Raul Castillo (Ecuador) and Zofia Bulinska-Radomska (Poland), are not in the photo, since they were occupied in delicate negotiations at the time.

Birmingham graduates and affiliate staff at the FAO conference in Leipzig, June 1996

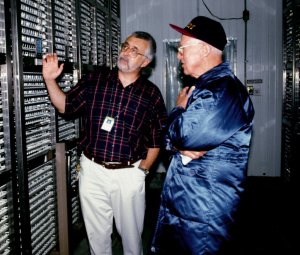

Dr J Trevor Williams (r). Behind him is Professor Jim Callow, Mason Professor of Botany. Behind Jim Callow is Jack Hawkes, and to his right (behind the tree) is Brian Ford-Lloyd. I am second from the left.

In 1969, two new members of staff were recruited to support the new MSc course. Dr J Trevor Williams (shown on the right in this photo taken at the 20th anniversary meeting at Birmingham in November 1989) acted as the course tutor, and lectured about plant variation.

Dr Richard Lester (who died in 2006) was a chemotaxonomist and Solanaceae expert. Trevor left Birmingham at the end of the 70s to become Executive Secretary, then Director General of the International Board for Plant Genetic Resources (which in turn became IPGRI, then Bioversity International).

Brian Ford-Lloyd (right, now Professor of Conservation Genetics and Director of the university Graduate School) joined the department in 1979 and was the course tutor for many years, and contributing lectures in data management, among others.

Brian Ford-Lloyd (right, now Professor of Conservation Genetics and Director of the university Graduate School) joined the department in 1979 and was the course tutor for many years, and contributing lectures in data management, among others.

With the pending retirement of Jack Hawkes in September 1982, I was appointed in April 1981 as a lecturer to teach evolution of crop plants, agroecology, and germplasm collecting among others, and to supervise dissertation research. I eventually supervised more than 25 MSc students in 10 years, some of whom continued for a PhD under my supervision (Susan Juned, Denise Clugston, Ghani Yunus, Javier Francisco-Ortega) as well as former students from Peru (René Chavez and Carlos Arbizú) who completed their PhD on potatoes working at CIP while registered at Birmingham. I was also the short course tutor for most of that decade.

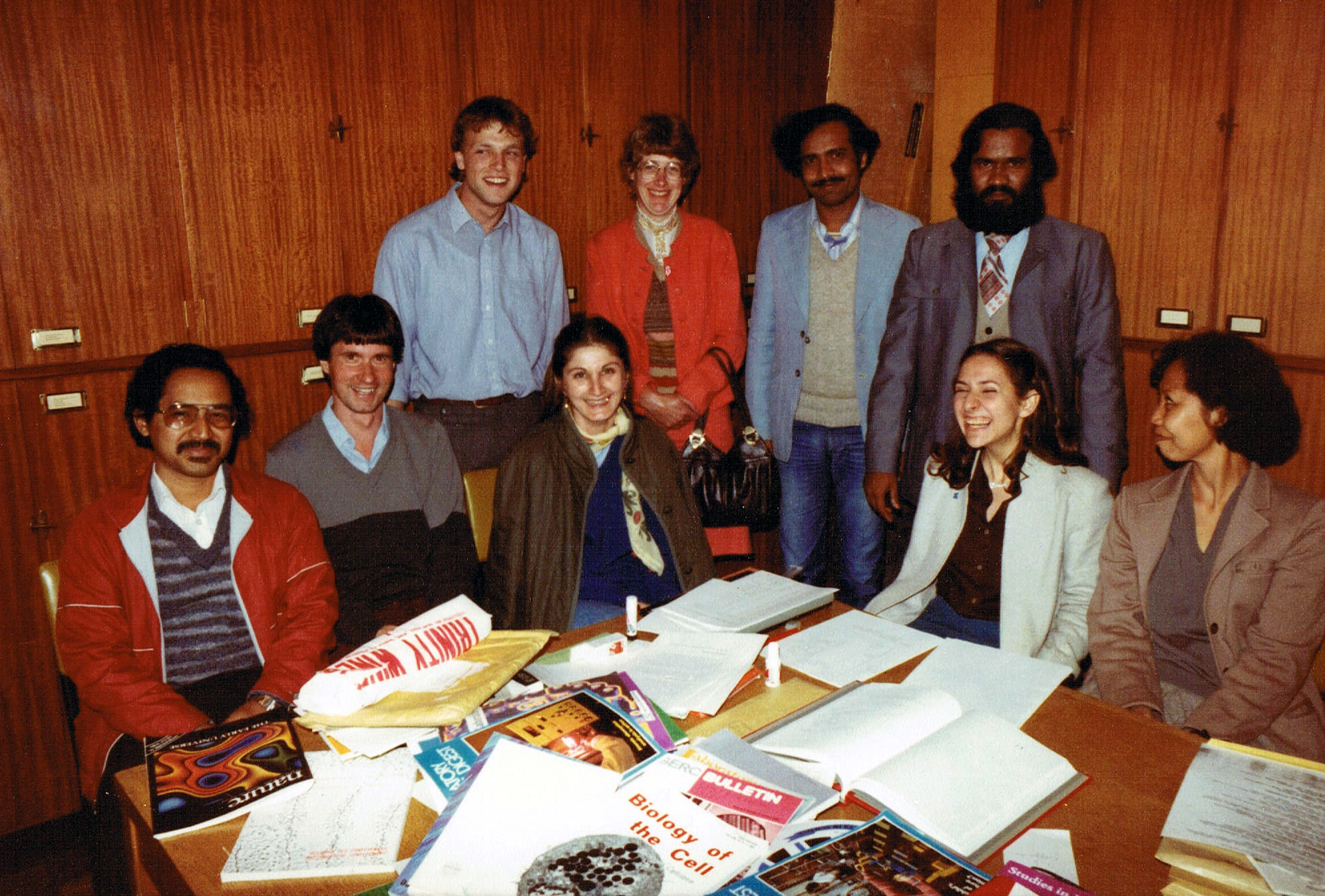

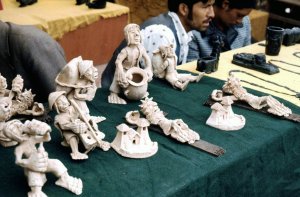

IBPGR provided funding not only for students, but supported the appointment of a seed physiologist, Dr Pauline Mumford until 1990. This was my first group of students who commenced their studies in September 1981. Standing are (l to r): Reiner Freund (Germany), Pauline Mumford, and two students from Bangladesh. Seated (l to r) are: Ghani Yunus (Malaysia), student from Brazil, Ayfer Tan (Turkey), Margarida Texeira (Portugal), student from Indonesia. Missing from that photo is Yen-Yuk Lo from Malaysia.

MSc students from Malaysia, Germany, Uruguay, Turkey, Portugal, Indonesia and Bangladesh. Dr Pauline Mumford, seed physiologist, stands in the second row.

The course celebrated its 20th anniversary in November 1989, and a group of ex-students were invited to Birmingham for a special workshop, sponsored by IBPGR. In the photo below are (l to r): Elizabeth Acheampong (Ghana), Indonesia, Trevor Williams, Yugoslavia, Zofia Bulinska-Radomska (Poland), India, Carlos Arbizu (Peru), Philippines, ??, Andrea Clausen (Argentina), Songkran Chitrakon (Thailand), ??.

Trevor Williams and former students at Birmingham in 1989 on the 20th anniversary of the MSc course

We also planted a medlar tree (Mespilus germanica); this photo was taken at the tree planting, and shows staff, past and current students.

Medlar planting to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the MSc course

After I resigned from the university to join IRRI in 1991, Dr Nigel Maxted (right) was appointed as a lecturer, and has continued his work on wild relatives of crop plants and in situ conservation. He has also taken students on field courses to the Mediterranean several times.

After I resigned from the university to join IRRI in 1991, Dr Nigel Maxted (right) was appointed as a lecturer, and has continued his work on wild relatives of crop plants and in situ conservation. He has also taken students on field courses to the Mediterranean several times.

I was privileged to attend Birmingham as a graduate student (I went on to complete a PhD under Jack Hawkes’ supervision) and become a member of the faculty. The University of Birmingham has made a very significant contribution to the conservation and use of plant genetic resources around the world.

Graduation December 1975

Today, hundreds of Birmingham graduates are involved daily in genetic conservation or helping to establish policy concerning access to and use of genetic resources around the world. Their work has ensured the survival of agrobiodiversity and its use to increase the productivity of crops upon which the world’s population depends.

* Mather was Vice Chancellor (= CEO) of the University of Southampton when I was an undergraduate there from 1967-1970. After retirement from Southampton, Mather returned to Birmingham and had an office in the Department of Genetics. In the late 1980s when I was teaching at Birmingham, and a member of the Genetics Group, I moved my office close-by Mather’s office, and we would frequently meet to discuss issues relating to genetic resources conservation and use. He often told me that a lot of what I mentioned was new to him – especially the genepool concept of Harlan and de Wet, which had been the basis of a Genetics Group seminar by one of my PhD students, Ghani Yunus from Malaysia, who was working on Lathyrus sativus, the grasspea. Mather and I agreed to meet a few days later, but unfortunately we never met since he died of a heart attack in the interim.

** John Jinks was head of department when Nobel Laureate Sir Paul Nurse applied to the university in 1967. Without a foreign language qualification it looked like he would not be offered a place. Until Jinks intervened. Paul Nurse often states that had it not been for John Jinks, he would not have made it to university. Jinks was the head of the Agricultural Research Council when he died in 1987. He was chair of the interview panel when I was appointed to a lectureship in plant biology at Birmingham in April 1981.

*** Heslop-Harrison became Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, 1970-1976.

The weather was glorious – again – today. In fact, it’s more like early summer than the end of March (although the forecast is for low temperatures once again this weekend).

The weather was glorious – again – today. In fact, it’s more like early summer than the end of March (although the forecast is for low temperatures once again this weekend).

Kinver Edge is a red sandstone escarpment where, in centuries past, there was a small community of residents who carved homes from the soft sandstone. The cave dwellings, known as the Holy Austin Rock Houses, were occupied until the 1930s, after which they fell into disrepair. There are records of occupation in the 1700s, but it’s believed that the caves were occupied much earlier than that.

Kinver Edge is a red sandstone escarpment where, in centuries past, there was a small community of residents who carved homes from the soft sandstone. The cave dwellings, known as the Holy Austin Rock Houses, were occupied until the 1930s, after which they fell into disrepair. There are records of occupation in the 1700s, but it’s believed that the caves were occupied much earlier than that.

A rather interesting experiment was reported on the

A rather interesting experiment was reported on the

The

The

Brian Ford-Lloyd (right, now Professor of Conservation Genetics and Director of the university Graduate School) joined the department in 1979 and was the course tutor for many years, and contributing lectures in data management, among others.

Brian Ford-Lloyd (right, now Professor of Conservation Genetics and Director of the university Graduate School) joined the department in 1979 and was the course tutor for many years, and contributing lectures in data management, among others.

After I resigned from the university to join IRRI in 1991, Dr Nigel Maxted (right) was appointed as a lecturer, and has continued his work on wild relatives of crop plants and in situ conservation. He has also taken students on field courses to the Mediterranean several times.

After I resigned from the university to join IRRI in 1991, Dr Nigel Maxted (right) was appointed as a lecturer, and has continued his work on wild relatives of crop plants and in situ conservation. He has also taken students on field courses to the Mediterranean several times.

I can’t remember why I had always wanted to visit Peru. All I know is that since I was a small boy, Peru had held a big fascination for me. I used to spend time leafing through an atlas, and spending most time looking at the maps of South America, especially Peru. And I promised myself (in the way that you do when you’re small, and can’t see how it would ever happen) that one day I would visit Peru.

I can’t remember why I had always wanted to visit Peru. All I know is that since I was a small boy, Peru had held a big fascination for me. I used to spend time leafing through an atlas, and spending most time looking at the maps of South America, especially Peru. And I promised myself (in the way that you do when you’re small, and can’t see how it would ever happen) that one day I would visit Peru. To cut a long story short, I didn’t go in 1971, but landed in Lima at the beginning of January 1973 after a long and gruelling flight on B.O.A.C. from London via Antigua (in the Caribbean), Caracas, and Bogotá.

To cut a long story short, I didn’t go in 1971, but landed in Lima at the beginning of January 1973 after a long and gruelling flight on B.O.A.C. from London via Antigua (in the Caribbean), Caracas, and Bogotá.

Oatcakes? These aren’t the crispy biscuits you buy in Scotland. Oh no! They are a delicious, thin, grilled ‘pancake’ made from fermented oat flour, served hot with delicious fillings of bacon, sausages, cheese, and eggs, and have been a traditional

Oatcakes? These aren’t the crispy biscuits you buy in Scotland. Oh no! They are a delicious, thin, grilled ‘pancake’ made from fermented oat flour, served hot with delicious fillings of bacon, sausages, cheese, and eggs, and have been a traditional  But there’s another Staffordshire delicacy – love it or hate it (in my case, ‘hate it’) – and that’s Marmite, a yeast extract by-product of the brewing industry. Marmite comes from Burton-upon-Trent, and the ‘Marmite odour’ is quite rich at times during the summer as you drive through the town.

But there’s another Staffordshire delicacy – love it or hate it (in my case, ‘hate it’) – and that’s Marmite, a yeast extract by-product of the brewing industry. Marmite comes from Burton-upon-Trent, and the ‘Marmite odour’ is quite rich at times during the summer as you drive through the town.

And germplasm collecting was repeated in Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam in Asia, and countries in East and southern Africa including Uganda and Madagascar, as well as Costa Rica in Central America (for wild rices). We invested a lot of efforts to train local scientists in germplasm collecting methods. Long-time IRRI employee (now retired) and genetic resources specialist, Eves Loresto (right), visited Bhutan on several occasions.

And germplasm collecting was repeated in Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam in Asia, and countries in East and southern Africa including Uganda and Madagascar, as well as Costa Rica in Central America (for wild rices). We invested a lot of efforts to train local scientists in germplasm collecting methods. Long-time IRRI employee (now retired) and genetic resources specialist, Eves Loresto (right), visited Bhutan on several occasions.

The genebank now has three storage vaults (one was added in the last couple of years) for medium-term (Active) and long-term (Base) conservation. Rice varieties are grown on the IRRI farm, and carefully dried before storage. Seed viability and health is always checked, and resident seed physiologist, Fiona Hay (right, formerly at the

The genebank now has three storage vaults (one was added in the last couple of years) for medium-term (Active) and long-term (Base) conservation. Rice varieties are grown on the IRRI farm, and carefully dried before storage. Seed viability and health is always checked, and resident seed physiologist, Fiona Hay (right, formerly at the

In early 1974 I travelled to southern Peru with a taxonomist friend from the University of St Andrews, Dr Peter Gibbs (right).

In early 1974 I travelled to southern Peru with a taxonomist friend from the University of St Andrews, Dr Peter Gibbs (right).

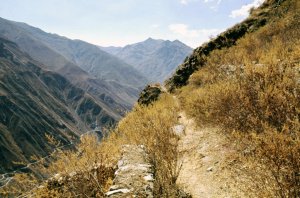

The drive south in a small Land Rover – down the coastal desert Panamericana highway, across the Nasca plain, climbing to Arequipa, and even higher to Puno – took three days. After resting up in Puno (next to Lake Titicaca), and getting used to the 3827 m altitude, we set off for Cuyo Cuyo. Dropping down from the altiplano at well over 4000 m, Cuyo Cuyo lies at an altitude of about 3300 m. Below the village the valley drops quickly towards the ceja de la montaña – literally ‘eyebrow of the mountain’ – where the humid air of the rainforests below rises up east-facing valleys to form cloud forest.

The drive south in a small Land Rover – down the coastal desert Panamericana highway, across the Nasca plain, climbing to Arequipa, and even higher to Puno – took three days. After resting up in Puno (next to Lake Titicaca), and getting used to the 3827 m altitude, we set off for Cuyo Cuyo. Dropping down from the altiplano at well over 4000 m, Cuyo Cuyo lies at an altitude of about 3300 m. Below the village the valley drops quickly towards the ceja de la montaña – literally ‘eyebrow of the mountain’ – where the humid air of the rainforests below rises up east-facing valleys to form cloud forest.

Peter and I set up camp, so-to-speak, in the local post office where we could sleep, brew the odd cup of tea (there was a small café in the village where we could eat), and gather our specimens together, including a rudimentary drier for the extensive set of oca herbarium samples that Peter intended to make. But more of that particular story later.

Peter and I set up camp, so-to-speak, in the local post office where we could sleep, brew the odd cup of tea (there was a small café in the village where we could eat), and gather our specimens together, including a rudimentary drier for the extensive set of oca herbarium samples that Peter intended to make. But more of that particular story later. The sides of the Cuyo Cuyo valley are covered with the most wonderful system of agricultural terraces, called andenes, which must have been constructed centuries ago, in Inca times, and have been cultivated ever since. Farmers have different terraces dotted around the valley, and when I was there, at least, farmers were still using a communal rotation system. Thus in one part of the valley the terraces were covered in potatoes (year 1 after a fallow), and oca (years 2 and 3), barley or beans (year 4), or fallow (years 5-8) elsewhere. Sheep are corralled on a terrace prior to planting potatoes, and their urine and dung used as fertilizer. Whether, almost 40 years later, this remains the case I do not know.

The sides of the Cuyo Cuyo valley are covered with the most wonderful system of agricultural terraces, called andenes, which must have been constructed centuries ago, in Inca times, and have been cultivated ever since. Farmers have different terraces dotted around the valley, and when I was there, at least, farmers were still using a communal rotation system. Thus in one part of the valley the terraces were covered in potatoes (year 1 after a fallow), and oca (years 2 and 3), barley or beans (year 4), or fallow (years 5-8) elsewhere. Sheep are corralled on a terrace prior to planting potatoes, and their urine and dung used as fertilizer. Whether, almost 40 years later, this remains the case I do not know.

I first heard her singing only three or four years ago – one of her tracks had been selected by a guest on a radio program I was listening to in the car. And I was smitten. She has one of the most remarkable voices in the recording industry today – and she’s also a very accomplished fiddle player.

I first heard her singing only three or four years ago – one of her tracks had been selected by a guest on a radio program I was listening to in the car. And I was smitten. She has one of the most remarkable voices in the recording industry today – and she’s also a very accomplished fiddle player.

In the 1960s the world faced a huge challenge: how to feed an ever-increasing population, especially in the poorer, developing countries with large agriculture-based societies.

In the 1960s the world faced a huge challenge: how to feed an ever-increasing population, especially in the poorer, developing countries with large agriculture-based societies.

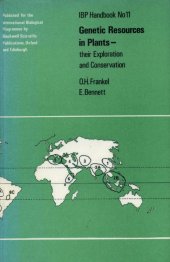

In preparation for Birmingham, I’d been advised to purchase and absorb a book that was published earlier that year, edited by Sir Otto Frankel and Erna Bennett [1] on genetic resources, and dedicated to NI Vavilov. And I came across Vavilov’s name for the first time in the first line of the Preface written by Frankel, and in the first chapter on Genetic resources by Frankel and Bennett. I should state that this was at the beginning of the genetic resources movement, a term coined by Frankel and Bennett at the end of the 60s when they had mobilized efforts to collect and conserve the wealth of diversity of crop varieties (and their wild relatives) – often referred to as landraces – grown all around the world, but were in danger of being lost as newly-bred varieties were adopted by farmers. The so-called Green Revolution had begun to accelerate the replacement of the landrace varieties, particularly among cereals like wheat and rice.

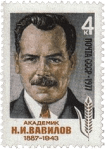

In preparation for Birmingham, I’d been advised to purchase and absorb a book that was published earlier that year, edited by Sir Otto Frankel and Erna Bennett [1] on genetic resources, and dedicated to NI Vavilov. And I came across Vavilov’s name for the first time in the first line of the Preface written by Frankel, and in the first chapter on Genetic resources by Frankel and Bennett. I should state that this was at the beginning of the genetic resources movement, a term coined by Frankel and Bennett at the end of the 60s when they had mobilized efforts to collect and conserve the wealth of diversity of crop varieties (and their wild relatives) – often referred to as landraces – grown all around the world, but were in danger of being lost as newly-bred varieties were adopted by farmers. The so-called Green Revolution had begun to accelerate the replacement of the landrace varieties, particularly among cereals like wheat and rice. Vavilov died of starvation in prison at the relatively young age of 55, following persecution under Stalin through the shenanigans of the charlatan Trofim Lysenko. Lysenko’s legacy also included the rejection of Mendelian genetics in the Soviet Union for many years. Eventually Vavilov was rehabilitated, long after his death, and he was commemorated on postage stamps at the time of his centennial.

Vavilov died of starvation in prison at the relatively young age of 55, following persecution under Stalin through the shenanigans of the charlatan Trofim Lysenko. Lysenko’s legacy also included the rejection of Mendelian genetics in the Soviet Union for many years. Eventually Vavilov was rehabilitated, long after his death, and he was commemorated on postage stamps at the time of his centennial. First,

First,

I’m not really a movie buff. In fact I can’t remember the last time I went to the cinema. It might even have been 1977 when I saw Star Wars in San José, Costa Rica. But I do catch the odd movie from time-to-time on the TV, and I particularly like westerns and musicals (although I still haven’t seen The Sound of Music*). The musicals of the thirties were something special and surrealistic – especially those directed by

I’m not really a movie buff. In fact I can’t remember the last time I went to the cinema. It might even have been 1977 when I saw Star Wars in San José, Costa Rica. But I do catch the odd movie from time-to-time on the TV, and I particularly like westerns and musicals (although I still haven’t seen The Sound of Music*). The musicals of the thirties were something special and surrealistic – especially those directed by

As I browsed the BBC news website this morning, I came across a magazine article about dress code (

As I browsed the BBC news website this morning, I came across a magazine article about dress code ( Morning suit or lounge suit? Over the course of my professional career I’ve never had to wear a suit, and frankly, never really feel very comfortable in one. And I’ve only ever worn a formal morning suit twice—at the weddings of my eldest brother Martin, and my cousin Diana. In the end, I chose what I knew I would be most comfortable wearing, and opted instead for my charcoal grey, lightweight suit that I had purchased only a couple of years ago or so, and had worn only a few times (there’s not much demand for suits in the Tropics). My friend and former colleague, John Sheehy (left)—who received his OBE at an investiture on 14 February—decided on a morning suit, and very elegant he looked too.

Morning suit or lounge suit? Over the course of my professional career I’ve never had to wear a suit, and frankly, never really feel very comfortable in one. And I’ve only ever worn a formal morning suit twice—at the weddings of my eldest brother Martin, and my cousin Diana. In the end, I chose what I knew I would be most comfortable wearing, and opted instead for my charcoal grey, lightweight suit that I had purchased only a couple of years ago or so, and had worn only a few times (there’s not much demand for suits in the Tropics). My friend and former colleague, John Sheehy (left)—who received his OBE at an investiture on 14 February—decided on a morning suit, and very elegant he looked too. In November 2010, on my way to attend a major international rice congress in Hanoi, Vietnam, I’d purchased a couple of silk ties at Birmingham airport. Both were plain colours – no stripes, patterns or what have you. Just plain coral pink and apple green (if plain is the appropriate description).

In November 2010, on my way to attend a major international rice congress in Hanoi, Vietnam, I’d purchased a couple of silk ties at Birmingham airport. Both were plain colours – no stripes, patterns or what have you. Just plain coral pink and apple green (if plain is the appropriate description). In the end, I went with my instincts, and settled on the pink tie. And even if I say so myself, very smart it looked, and certainly (k)not out of place.

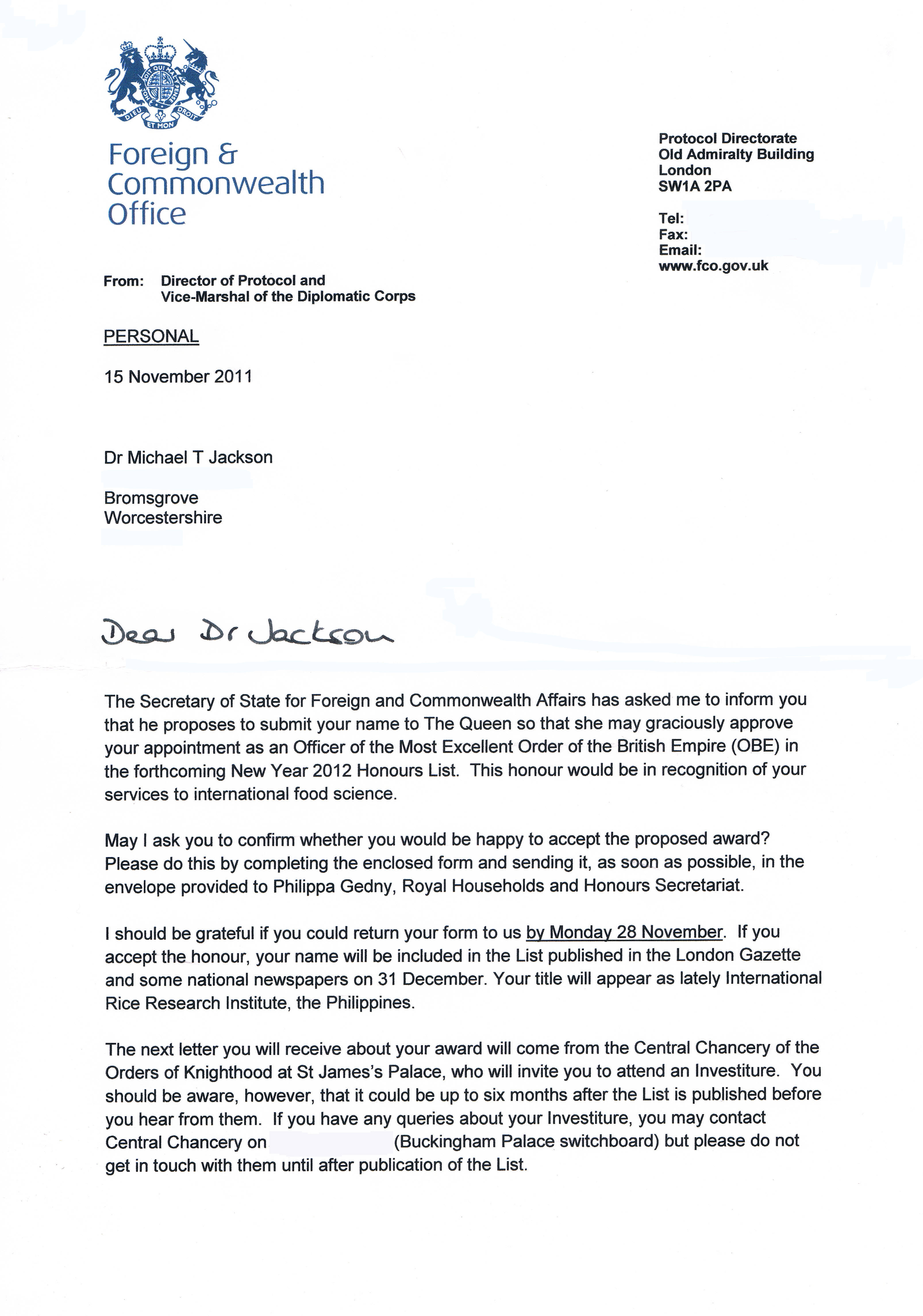

In the end, I went with my instincts, and settled on the pink tie. And even if I say so myself, very smart it looked, and certainly (k)not out of place. On a bright, sunny day last November (my birthday, actually) I was outside cleaning the car, when the postman passed by. He handed me several envelopes and my immediate reaction was that this was another load of the usual junk mail. So you can imagine my surprise when I came across one that seemed rather official looking. And I was even more surprised when I read what it had to say – that I had been nominated to become an Officer of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, or OBE, for services to international food science. Well, I was gob-smacked, quite emotional really. I rushed inside to tell Steph – who was equally stunned, and we set to ponder how on earth this had come about. I did some Google detective work, and was able to find out a little more about the

On a bright, sunny day last November (my birthday, actually) I was outside cleaning the car, when the postman passed by. He handed me several envelopes and my immediate reaction was that this was another load of the usual junk mail. So you can imagine my surprise when I came across one that seemed rather official looking. And I was even more surprised when I read what it had to say – that I had been nominated to become an Officer of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, or OBE, for services to international food science. Well, I was gob-smacked, quite emotional really. I rushed inside to tell Steph – who was equally stunned, and we set to ponder how on earth this had come about. I did some Google detective work, and was able to find out a little more about the