A few days ago, with a fair to promising weather forecast (it actually turned out much brighter and warmer than expected) we made another of our National Trust visits – this time to Calke Abbey, near the village of Ticknall which lies just to the southeast of Derby (of Rolls Royce aeroengines fame), in the English Midlands.

A few days ago, with a fair to promising weather forecast (it actually turned out much brighter and warmer than expected) we made another of our National Trust visits – this time to Calke Abbey, near the village of Ticknall which lies just to the southeast of Derby (of Rolls Royce aeroengines fame), in the English Midlands.

Calke Abbey (incidentally there was never an abbey there, although there had been an Augustinian priory in the vicinity from the 13th century) is a country house, rebuilt between 1701 and 1704 – amid several hundred acres of farm and park land (including a deer park) – by Sir John Harpur, the 4th baronet. His impressive memorial was built in St Giles Church on the Calke Abbey estate.

The original estate was purchased by the 1st baronet in 1622, and remained in the Harpur family until 1985. Sir John Harpur married a daughter of Lord Crewe, and at some date thereafter the family name was changed to Crewe, and then Harpur Crewe. The last baronet died in the early 20s, and the estate passed to a grandson, Charles Jenney – who changed his name to Harpur Crewe. When he died in 1981, the estate was faced with crippling death duties, and like so many ‘stately homes’ it began to deteriorate because the family could no longer afford its upkeep. In 1985 ownership passed to the National Trust. And what a treasure trove the Trust encountered!

It seems the Harpur Crewes were mildly eccentric, didn’t have electricity installed in the house until 1962, and almost never threw anything away – they were great hoarders. So when the National Trust came to inventory the house and its contents, they found a property that consisted entirely of its original contents. Whole rooms, such as the dining room, were furnished just as they had been originally completed in the 18th century.

Normally the National Trust acquires various items and displays them in its different properties according to the period or aspect they want to emphasise. But not so with Calke Abbey – nothing has been brought in. Although extensive roof repairs had to be carried out, there has been remarkably little water damage in the house. Even when the house was occupied, different wings were abandoned after the Second World War, and essentially left to their own devices and deteriorate (these had the feel perhaps of Miss Havisham’s house in Great Expectations by Victorian author and one of the world’s greatest novelists, Charles Dickens).

In the case of Calke Abbey, the National Trust took the decision to repair the fabric of the building (to reduce further deterioration) but not to renovate. So it’s quite fascinating to move through the house and see those parts which continued to be occupied, and those which had been shut up for decades.

In the entrance hall and lobby there is a number of stuffed heads of longhorn cattle that were once farmed on the estate. In fact, the house is full of stuffed heads of deer – they are everywhere – and throughout the house there are dozens of glass cases of stuffed birds, mainly of British origin, but also fine examples from around the world. It’s a taxidermist’s paradise.

In the caricature room the walls are covered with 18th century cartoons relating to politics and society at that time.

In the caricature room the walls are covered with 18th century cartoons relating to politics and society at that time.

The main staircase is very impressive, and is made from oak and yew.

The main staircase is very impressive, and is made from oak and yew.

But it’s in the dining room, the breakfast room, and the saloon that the glory of Calke Abbey comes to the fore. The original plasterwork is still intact and speaks volumes for the quality of the craftsmanship of the 18th century.

The bedroom of Sir Vauncey Harpur Crewe remains apparently much as it was when he abandoned it for another when he was married in 1876.

On the National Trust website, it’s possible to take a virtual tour of Calke Abbey, which certainly gives you a feel for the house and its contents. I have also posted a web album where you can see many more photos from inside the house and the park and gardens.

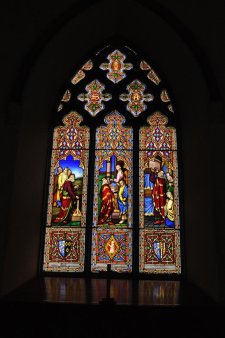

A short distance from the house stands St Giles Church, and there is a beautiful stained glass window above the altar that was installed by Sir George Crewe who died in 1844.

There is a formal garden, and a walled kitchen garden (that was formally much larger) in addition to the farm and parkland. And two very interesting features are the tunnels that connect the gardens with the house, and one from the wine cellars in the house to the brew house, alongside the stable yard. This tunnel weaves for about 100 m, and allowed domestic staff to pass from the house to the brew house without being seen!

Calke Abbey was certainly more than I had expected, and is a fascinating insight to 18th and 19th century living.