Nikolai Vavilov

Russian geneticist and plant breeder Nikolai Vavilov (1887-1943) is a hero of mine. He died, a Soviet prisoner, five years before I was born.

Until I began my graduate studies in the Department of Botany at the University of Birmingham in the conservation and use of plant genetic resources (i.e., crops and their wild relatives) almost 50 years ago in September 1970, his name was unknown to me. Nevertheless, Vavilov’s prodigious publications influenced the career I subsequently forged for myself in genetic conservation.

At the same time I was equally influenced by my mentor and PhD supervisor Professor Jack Hawkes, at Birmingham, who met .

At the same time I was equally influenced by my mentor and PhD supervisor Professor Jack Hawkes, at Birmingham, who met .

Vavilov undoubtedly laid the foundations for the discipline of genetic resources —the collection, conservation, evaluation, and use of plant genetic resources for food and agriculture (PGRFA). It’s not for nothing that he is widely regarded as the Father of Plant Genetic Resources.

Almost 76 years on from his death, we now understand much more about the genetic diversity of crops than we ever dreamed possible, even as recently as the turn of the Millennium, thanks to developments in molecular biology and genomics. The sequencing of crop genomes (which seems to get cheaper and easier by the day) opens up significant opportunities for not only understanding how diversity is distributed among crops and species, but how it functions and can be used to breed new crop varieties that will feed a growing world population struggling under the threat of environmental challenges such as climate change.

These tools were not available to Vavilov. He used his considerable intellect and powers of observation to understand the diversity of many crop species (and their wild relatives) that he and his associates collected around the world. Which student of genetic resources can fail to be impressed by Vavilov’s theories on the origins of crops and how they varied among regions.

In my own small way, I followed in Vavilov’s footsteps for the next 40 years. I can’t deny that I was fortunate. I was in the right place at the right time. I had some of the best connections. I met some of the leading lights such as Sir Otto Frankel, Erna Bennett, and Jack Harlan, to name just three. I became involved in genetic conservation just as the world was beginning to take notice.

Knowing of my ambition to work overseas (particularly in South America), Jack Hawkes had me in mind in early 1971 when asked by Dr Richard Sawyer, the first Director General of the International Potato Center (CIP, based in Lima, Peru) to propose someone to join the newly-founded center to curate the center’s collection of Andean potato varieties. This would be just a one-year appointment while a Peruvian scientist received MSc training at Birmingham. Once I completed the MSc training in the autumn of 1971, I had some of the expertise and skills needed for that task, but lacked practical experience. I was all set to get on the plane. However, my recruitment to CIP was delayed until January 1973 and I had, in the interim, commenced a PhD project.

I embarked on a career in international agricultural research for development almost by serendipity. One year became a lifetime. The conservation and use of plant genetic resources became the focus of my work in two international agricultural research centers (CIP and IRRI) of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR), and during the 1980s at the University of Birmingham.

I embarked on a career in international agricultural research for development almost by serendipity. One year became a lifetime. The conservation and use of plant genetic resources became the focus of my work in two international agricultural research centers (CIP and IRRI) of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR), and during the 1980s at the University of Birmingham.

My first interest were grain legumes (beans, peas, etc.), and I completed my MSc dissertation studying the diversity and origin of the lentil, Lens culinaris whose origin, in 1970, was largely speculation.

Trevor Williams

Trevor Williams, the MSc Course tutor, supervised my dissertation. He left Birmingham around 1977 to become the head of the International Board for Plant Genetic Resources (IBPGR) in Rome, that in turn became the International Plant Genetic Resources Institute (IPGRI), and continues today as Bioversity International.

Joe Smartt

I guess that interest in legume species had been sparked by Joe Smartt at the University of Southampton, who taught me genetics and encouraged me in the first instance to apply for a place to study at Birmingham in 1970.

But the cold reality (after I’d completed my MSc in the autumn of 1971) was that continuing on to a PhD on lentils was never going to be funded. So, when offered the opportunity to work in South America, I turned my allegiance to potatoes and, having just turned 24, joined CIP as Associate Taxonomist.

From the outset, it was agreed that my PhD research project, studying the diversity and origin, and breeding relationships of a group of triploid (with three sets of chromosomes) potato varieties that were known scientifically as Solanum x chaucha, would be my main contribution to the center’s research program. But (and this was no hardship) I also had to take time each year to travel round Peru and collect local varieties of potatoes to add to CIP’s germplasm collection.

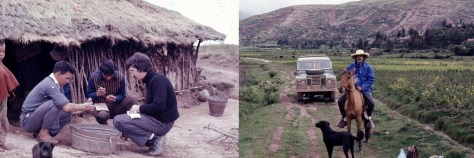

I explored the northern departments of Ancash and La Libertad (with my colleague Zósimo Huamán) in May 1973, and Cajamarca (on my own with a driver) a year later. Each trip lasted almost a month. I don’t recall how many new samples these trips added to CIP’s growing germplasm collection, just a couple of hundred at most.

Collecting potatoes from a farmer in Cajamarca, northern Peru in May 1974 (L); and getting ready to ride off to a nearby village, just north of Cuzco, in February 1974 (R).

In February 1974, I spent a couple of weeks in the south of Peru, in the department of Puno, studying the dynamics of potato cultivation on terraces in the village of Cuyo-Cuyo.

I made just one short trip with Jack Hawkes (and another CIP colleague, Juan Landeo) to collect wild potatoes in central Peru (Depts. of Cerro de Pasco, Huánuco, and Lima). It was fascinating to watch ‘the master’ at work. After all, Jack had been collecting wild potatoes the length of the Americas since 1939, and instinctively knew where to find them. Knowing their ecological preferences, he could almost ‘smell out’ each species.

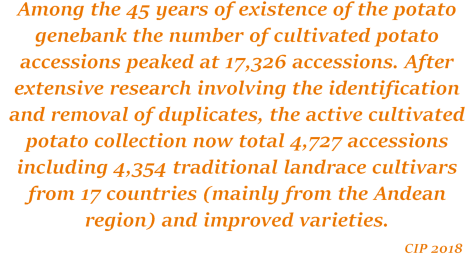

My research (and Zósimo’s) contributed to a better understanding of potato diversity in the germplasm collection, and the identification of duplicate clones. During the 1980s the size of the collection maintained as tubers was reduced, while seeds (often referred to as true potato seed, or TPS) was collected for most samples.

Potato varieties (representative ‘morphotypes’) of Solanum x chaucha that formed part of my PhD study. L-R, first row: Duraznillo, Huayro, Garhuash Shuito, Puca Shuito, Yana Shuito L-R, second row: Komar Ñahuichi, Pishpita, Surimana, Piña, Manzana, Morhuarma L-R, third row: Tarmeña, Ccusi, Yuracc Incalo L-R, fourth row: Collo, Rucunag, Hayaparara, Rodeñas

Roger Rowe

Dr Roger Rowe was my department head at CIP, and he became my ‘local’ PhD co-supervisor. A maize geneticist by training, Roger joined CIP in July 1973 as Head of the Department of Breeding & Genetics. Immediately prior to joining CIP, he led the USDA’s Inter-Regional Potato Introduction Project IR-1(now National Research Support Program-6, NRSP-6) at the Potato Introduction Station in Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin.

Although CIP’s headquarters is at La Molina on the eastern outskirts of Lima, much of my work was carried out in Huancayo, a six hour drive winding up through the Andes, where CIP established its highland field station. This is where we annually grew the potato collection.

Aerial view of the potato germplasm collection at the San Lorenzo station of CIP, near Huancayo in the Mantaro Valley, central Peru, in the mid-1970s.

During the main growing season, from about mid-November to late April (coinciding with the seasonal rainfall), I’d spend much of every week in Huancayo, making crosses and evaluating different varieties for morphological variation. This is where I learned not only all the practical aspects of conservation of a vegetatively-propagated crop, and many of the phytosanitary implications therein, but I also learned how to grow a crop of potatoes. Then back in Lima, I studied the variation in tuber proteins using a tool called polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (that, I guess, is hardly used any more) by separating these proteins across a gel concentration gradient, as shown diagrammatically in the so-called electrophoregrams below. Compared to what we can achieve today using a range of molecular markers, this technique was really rather crude.

Jack Hawkes visited CIP two or three times while I was working in Lima, and we would walk around the germplasm collection in Huancayo, discussing different aspects of my research, the potato varieties I was studying, and the results of the various crossing experiments.

With Jack Hawkes in the germplasm collection in Huancayo in January 1975 (L); and (R), discussing aspects of my research with Carlos Ochoa in a screenhouse at CIP in La Molina (in mid-1973).

I was also fortunate (although I realized it less at the time) to have another potato expert to hand: Professor Carlos Ochoa, who joined CIP (from the National Agrarian University across the road from CIP) as Head of Taxonomy.

Well, three years passed all too quickly, and by the end of May 1975, Steph and I were back in Birmingham for a few months while I wrote up and defended my dissertation. This was all done and dusted by the end of October that year, and the PhD was conferred at a congregation held at the university in December.

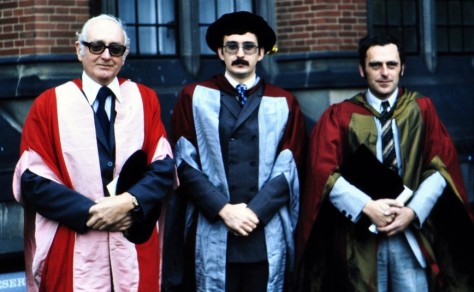

With Jack Hawkes (L) and Trevor Williams (R) after the degree congregation on 12 December 1975 at the University of Birmingham.

With that, the first chapter in my genetic resources career came to a close. But there was much more in store . . .

I remained with CIP for the next five years, but not in Lima. Richard Sawyer asked me to join the center’s Regional Research Program (formerly Outreach Program), initially as a post-doctoral fellow, the first to be based outside headquarters. Thus, in April 1976 (only 27 years old) I was posted to Turrialba, Costa Rica (based at a regional research center, CATIE) to set up a research project aimed at adapting potatoes to warm, humid conditions of the tropics. A year later I was asked to lead the regional program that covered Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean.

CATIE had its own germplasm collections, and just after I arrived there, a German-funded project, headed by Costarrican scientist Dr Jorge León, was initiated to strengthen the ongoing work on cacao, coffee, and pejibaye or peach palm, and other species. Among the young scientists assigned to that project was Jan Engels, who later moved to Bioversity International in Rome (formerly IBPGR, then IPGRI), with whom I have remained in contact all these years and published together. So although I was not directly involved in genetic conservation at this time, I still had the opportunity to observe, discuss and learn about crops that had been beyond my immediate experience.

It wasn’t long before my own work took a dramatically different turn. In July 1977, in the process of evaluating around 100 potato varieties and clones (from a collection maintained in Toluca, Mexico) for heat adaptation (no potatoes had ever been grown in Turrialba before), my potato plots were affected by an insidious disease called bacterial wilt (caused by the pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum).

(L) Potato plants showing typical symptoms of bacterial wilt. (R) An infected tuber exuding the bacterium in its vascular system.

Turrialba soon became a ‘hot spot’ for evaluating potato germplasm for resistance against bacterial disease, and this and some agronomic aspects of bacterial wilt control became the focus of much of my research over the next four years. I earlier wrote about this work in more detail.

This bacterial wilt work gave me a good grounding in how to carefully evaluate germplasm, and we went on to look at resistance to late blight disease (caused by the fungus Phytophthora infestans – the pathogen that caused the Irish Potato Famine of the 1840s, and which continues to be a scourge of potato production worldwide), and the viruses PVX, PVY, and PLRV.

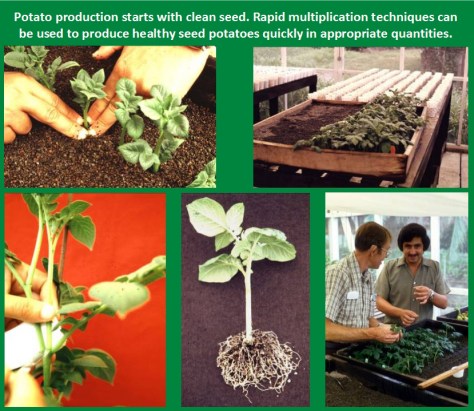

One of the most satisfying aspects of my work at this time was the development and testing of rapid multiplication techniques, so important to bulk up healthy seed of this crop.

My good friend and seed production specialist colleague Jim Bryan spent a year with me in Costa Rica on this project.

Throughout this period I was, of course, working more on the production side, learning about the issues that farmers, especially small farmers, face on a daily basis. It gave me an appreciation of how the effective use of genetic resources can raise the welfare of farmers and their families through the release of higher productivity varieties, among others.

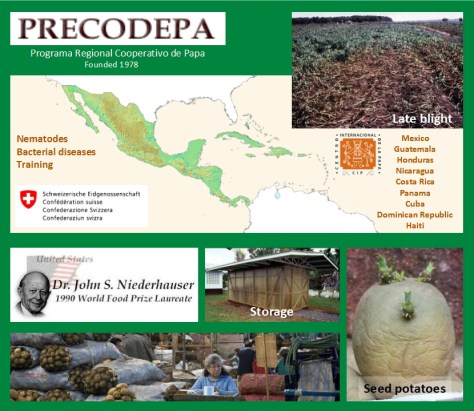

I suppose one activity that particularly helped me to hone my management skills was the setting up of PRECODEPA in 1978, a regional cooperative potato project involving six countries, from Mexico to Panama and the Dominican Republic. Funded by the Swiss, I had to coordinate and support research and production activities in a range of national agricultural research institutes. It was, I believe, the first consortium set up in the CGIAR, and became a model for other centers to follow.

I should add that PRECODEPA went from strength to strength. It continued for at least 25 years, funded throughout by the Swiss, and expanding to include other countries in Central America and the Caribbean.

However, by the end of 1980 I felt that I had personally achieved in Costa Rica and the region as much as I had hoped for and could be expected; it was time for someone else to take the reins. In any case, I was looking for a new challenge, and moved back to Lima (38 years ago today) to discuss options with CIP management.

It seemed I would be headed for pastures new, the southern cone of South America perhaps, even the Far East in the Philippines. But fate stepped in, and at the end of March 1981, Steph, daughter Hannah (almost three) and I were on our way back to the UK. To Birmingham in fact, where I had accepted a Lectureship in the Department of Plant Biology.

The subsequent decade at Birmingham opened up a whole new set of genetic resources opportunities . . .