Vindictive and vengeful, certainly.

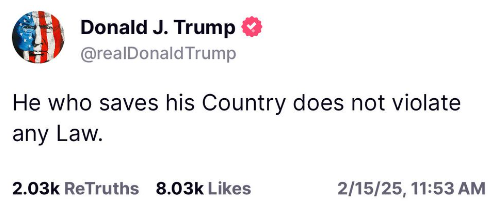

Emboldened by Donald Trump, ‘Department of Government Efficiency‘ or DOGE lead, Elon Musk – the world’s richest man – has taken a chainsaw (his words) to the departments, institutions, and agencies of the US federal government in a cruel and callous not to say careless way over the past few weeks since Trump’s inauguration on 20 January.

Elon Musk wielding a chainsaw at the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) at the Gaylord National Resort Hotel And Convention Center on 20 February 2025 in Oxon Hill, Maryland.

That’s not to deny that inefficiencies can be found and budgetary savings made in any government, and I’m sure the US federal government is no different from any other. But to proceed, as Musk and his acolytes have, is causing possibly irreparable damage on a daily basis, thousands of federal employees are losing their jobs, and this ‘downsizing’ has been effected in, it seems, an indiscriminate way. Last in, first out, and hang the consequences.

As billionaire entrepreneur Mark Cuban posted on Bluesky (@mcuban.bsky.social) a few hours ago:

As billionaire entrepreneur Mark Cuban posted on Bluesky (@mcuban.bsky.social) a few hours ago:

Ready Aim Fire is a lousy way to govern.

Has it only been five weeks? It feels more like five years. And already the harm is being done, supported by some of probably the most incompetent and least qualified departmental secretaries (RFK Jr at Health and Pete Hegseth at Defense come immediately to mind, but there are many others, although yesterday Musk declared that Trump’s Cabinet was the most qualified of all time).

Certainly it looks like Musk is on some sort of ego trip. Or perhaps an over-enthusiastic substance-fuelled trip, as Musk has himself acknowledged his use of the same.

I’m not going to comment of the long list of agencies that DOGE has gone after, and having done the damage has had to roll back some of his actions, not entirely with success.

But I would like to comment on two areas that I do have some experience in, and have had contact over the years, directly and indirectly.

It’s beyond comprehension that, seemingly on a whim, DOGE abolished the world’s biggest (although not meeting the UN target of 0.7% of Gross National Income or GNI) and perhaps most important development agency, the United States Agency for International Development or USAid (now subsumed into the State Department).

It’s beyond comprehension that, seemingly on a whim, DOGE abolished the world’s biggest (although not meeting the UN target of 0.7% of Gross National Income or GNI) and perhaps most important development agency, the United States Agency for International Development or USAid (now subsumed into the State Department).

Here’s how USAid compared to other foreign government development aid agencies:

Donald Trump and Elon Musk have hit foreign aid harder and faster than almost any other target in their push to cut the size of the federal government. Both men say USAid projects advance a liberal agenda and are a waste of money. (The Guardian, 27 February 2025).

Seems like charity begins at home. Except that the savings won’t be passed on to Mr and Mrs Average American. Wait for the tax cuts for the already rich.

Those cuts at USAid immediately affected humanitarian, health, and agricultural support programs around the world, as personnel were recalled to the US (I have a number of close friends who worked for USAid in the US or abroad), and an immediate ban on further program expenditures implemented. But it’s not just overseas that USAid’s demise will be felt. USAid was a huge purchaser of home-grown grains for donation to the World Food Program or directly to nations suffering food shortages. US farmers will reap the harvest of Musk’s misguided ‘efficiencies’.

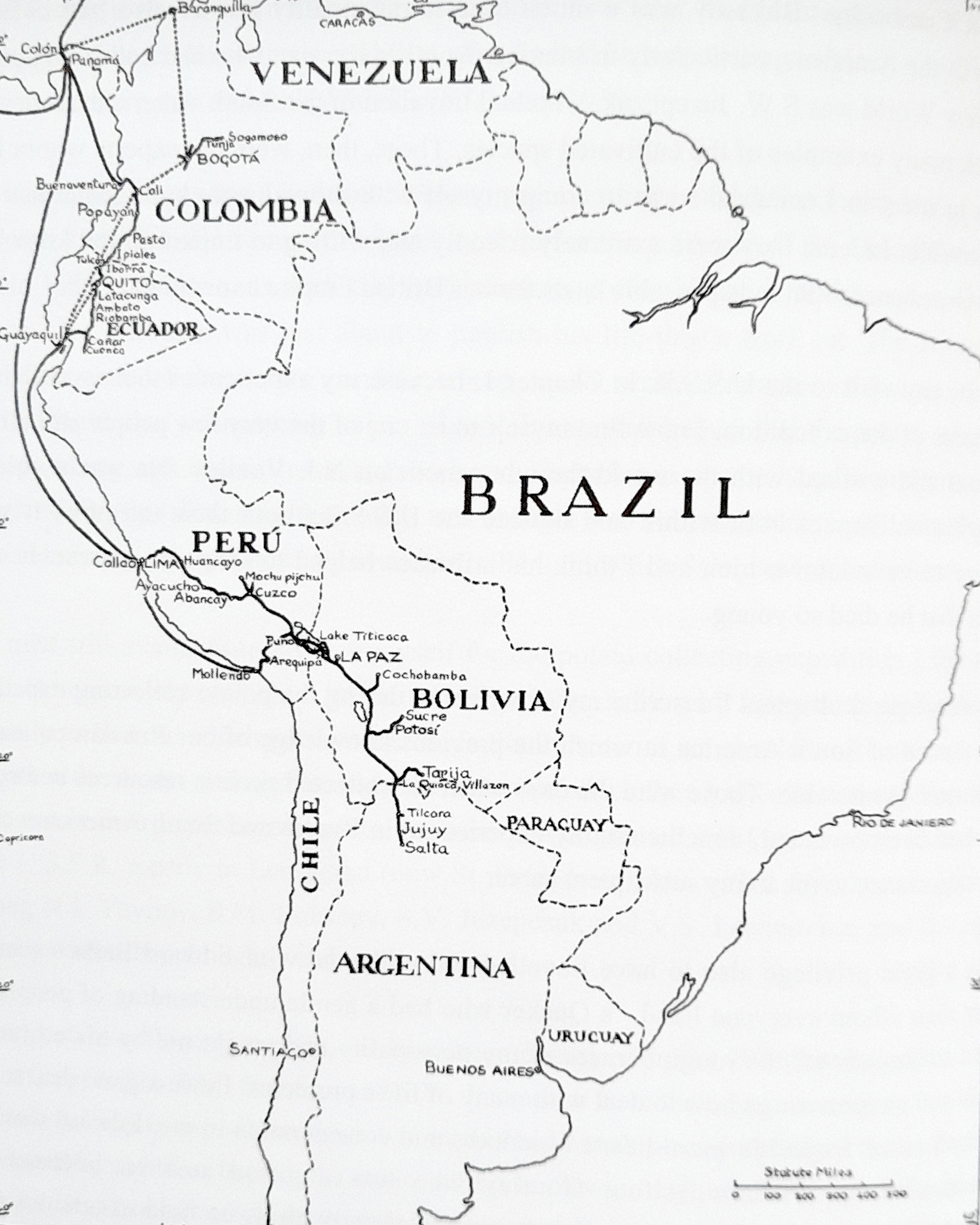

For almost 30 years I worked at two (of 14) centers—the International Potato Center (CIP) and the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI)—of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research or CGIAR.

For almost 30 years I worked at two (of 14) centers—the International Potato Center (CIP) and the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI)—of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research or CGIAR.

For 2025, the CGIAR had a proposed budget of around USD1 billion, funded through a consortium of donor agencies, and various funding mechanisms. In the past, USAid was one of the largest and most important supporters of the CGIAR. Termination of its funding, if indeed this is what is about to happen, will severely impact how the research centers can continue to operate effectively, and I fear that programs will be cut, and staff let go [1].

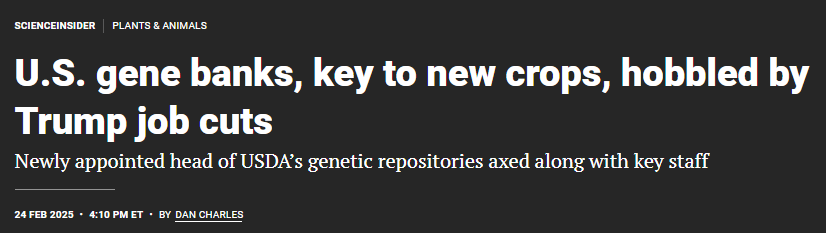

The other area of concern with regard to the Trump/Musk attack on federal agencies relates to the long-term safety of the nation’s genetic resources collections managed by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA).

In this recent article in Science (just click on the headline below to open) the range of cuts is described and the pushback from agribusiness.

Plant breeder Neha Kothari (right) was hired in October 2024 to streamline and improve the department’s vast collections of seeds and living crops that are key to developing improved  varieties. But on 13 February she, like tens of thousands of other recent hires across the government still in probationary status, was dismissed from her job. [2]

varieties. But on 13 February she, like tens of thousands of other recent hires across the government still in probationary status, was dismissed from her job. [2]

The entire gene bank network felt the chainsaw wielded by Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency. About 30 employees—10% of its total staff—were terminated, according to an informal survey by some retired USDA scientists. An additional 10 vacant positions have been frozen or rescinded, and a similar number took Musk’s offer last month to resign immediately but remain on the federal payroll through September.

When I started my career in genetic resources conservation 55 years ago, there was a vision and hope that one day the global system of genebanks would be properly funded. Now, with funding  from the Crop Trust, that vision is being realised. And just as the genebank system is being stabilised, DOGE’s attack on the USDA’s germplasm system is unprecedented as well as a totally misguided action by incompetent DOGE staff who, it seems across a wide range of sectors, simply do not have the knowledge, expertise, or experience to make the sorts of ‘chainsaw’ decisions they are inflicting on the federal government.

from the Crop Trust, that vision is being realised. And just as the genebank system is being stabilised, DOGE’s attack on the USDA’s germplasm system is unprecedented as well as a totally misguided action by incompetent DOGE staff who, it seems across a wide range of sectors, simply do not have the knowledge, expertise, or experience to make the sorts of ‘chainsaw’ decisions they are inflicting on the federal government.

Which brings me on to a final point. There’s something particularly obscene that the world’s richest man is holding sway over the lives of hundreds of thousands of federal employees (and the nation at large) even while his own companies receive federal grants and contracts reported to be in excess of USD13 billion. I wonder if he’s going after those agencies from which he receives such business largesse? Talk about conflict of interest.

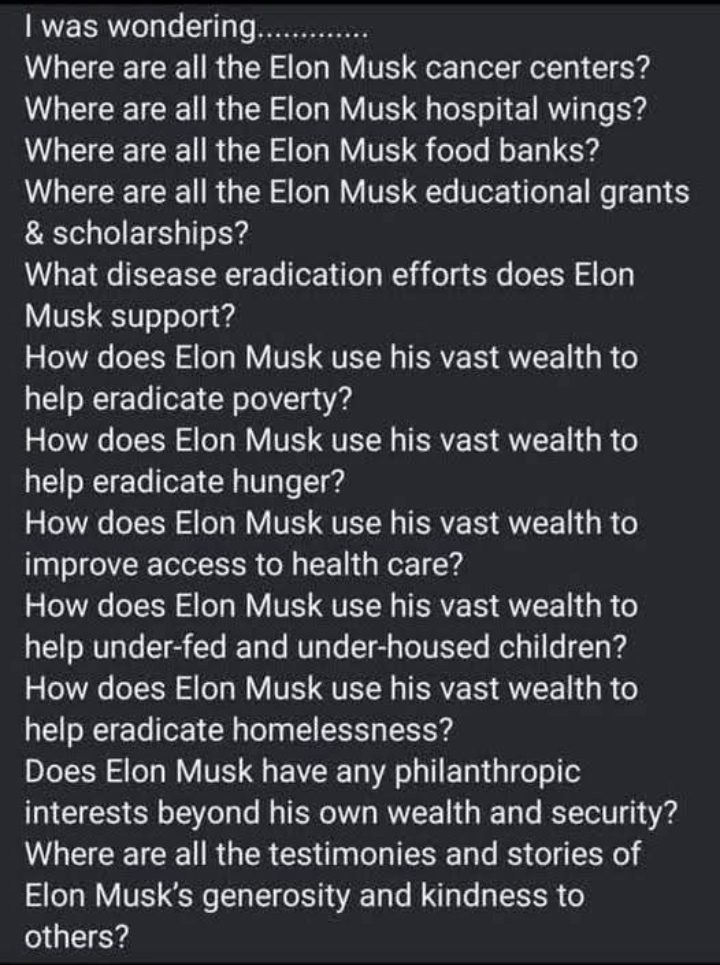

I came across this list of questions about Musk and his wealth which someone posted on Bluesky recently:

Says so much. Just to put Musk’s wealth into perspective. If he was to give away USD1 million a day, it would take over 1000 years to disburse the lot! As far as anyone can tell, Musk has not engaged in any (or very little – I stand to be corrected) philanthropic endeavours.

With his wealth, he could fund the Crop Trust and global genebank activities in perpetuity with just a USD1 billion donation. Loose change for him.

Click here to read the Crop Trust Annual Report for 2023 which explains just how its funding is used to preserve and use the world’s crop genetic heritage.

Not all billionaires are like Musk. At least two billionaires, Bill Gates (with ex-wife Melinda) and Warren Buffet put their money where their mouths are in setting up the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (now the Gates Foundation) that has funded many humanitarian efforts globally, at USD7.7 billion in 2023. While the GF has come in for criticism on several levels, there’s no doubt that its programs have brought about or facilitated real change. Where does Musk stand in this respect? Invisible!

[1] In a news conference a couple of days ago, UK Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer announced an increase in the nation’s defence budget – at the expense of the overseas aid and development budget. That had already been cut under the previous Conservative government in 2021 from the UN target of 0.7% of GNI (enshrined in law in 2015). The aid budget has been slashed to 0.3% of GNI. The UK is an important donor to the CGIAR, and this reduction is a double whammy (along with USAid) for future CGIAR prospects.

[2] Update from Science, 24 February, 5:35 pm: Science has learned that USDA is reinstating Neha Kothari as leader of the department’s national program on plant genetic resources. Kothari joins several other top-tier government scientists whose firings have been reversed, but so far there is no indication that USDA has reinstated other fired germplasm system staff. Academic leaders and representatives from the agricultural industry had criticized Kothari’s dismissal.

Memories. Powerful; fleeting; joyful; or sad. Sometimes, unfortunately, too painful and hidden away in the deepest recesses of the mind, only to be dragged to the surface with great reluctance.

Memories. Powerful; fleeting; joyful; or sad. Sometimes, unfortunately, too painful and hidden away in the deepest recesses of the mind, only to be dragged to the surface with great reluctance.

I grew up believing that—despite the suitability or not of the occupant—one should respect the office of a Prime Minister or President.

I grew up believing that—despite the suitability or not of the occupant—one should respect the office of a Prime Minister or President.

And he unleashed mad dogs in the form of Elon Musk and his cohort of employees from the so-called ‘Department for Government Efficiency’ (DOGE) with, it seems, carte blanche authority to do whatever he pleases.

And he unleashed mad dogs in the form of Elon Musk and his cohort of employees from the so-called ‘Department for Government Efficiency’ (DOGE) with, it seems, carte blanche authority to do whatever he pleases.

It was about the

It was about the

Among the species identified in the course of Jack’s dissertation research was Solanum ballsii from northern Argentina, which he dedicated to EK Balls in a formal description in 1944. However, in his 1963 revised taxonomy of the tuber-bearing Solanums (potatoes), Jack (with his Danish colleague Jens Peter Hjerting, 1917-2012) recognized Solanum ballsii simply as a subspecies of Solanum vernei, a species which has since provided many important sources of resistance to the potato cyst nematode.

Among the species identified in the course of Jack’s dissertation research was Solanum ballsii from northern Argentina, which he dedicated to EK Balls in a formal description in 1944. However, in his 1963 revised taxonomy of the tuber-bearing Solanums (potatoes), Jack (with his Danish colleague Jens Peter Hjerting, 1917-2012) recognized Solanum ballsii simply as a subspecies of Solanum vernei, a species which has since provided many important sources of resistance to the potato cyst nematode.

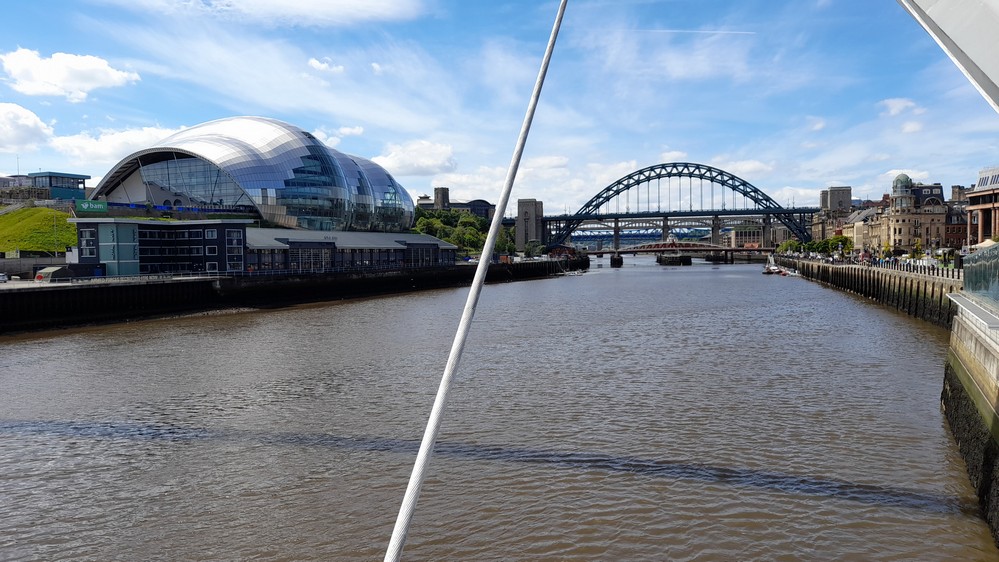

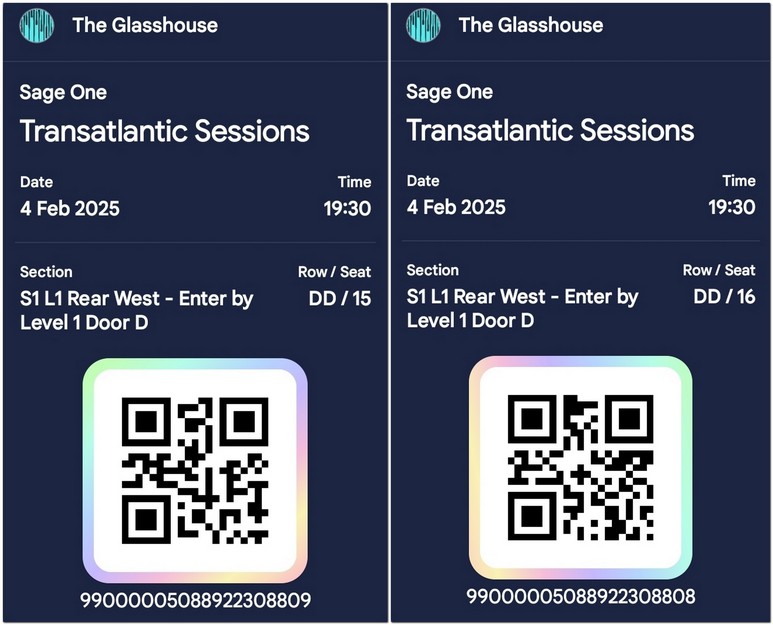

Before those two concerts it must have been almost 30+ years since I’d attended any live concert, while I was still at university.

Before those two concerts it must have been almost 30+ years since I’d attended any live concert, while I was still at university.