Almost 2000 years.

English Heritage preserves several important sites in Cornwall, and during our week long break there, we got to visit four that span about 2000 years of British history, from the Roman occupation of these islands, through the Dark Ages, the 12th century under the Normans, and from the Tudors until the Second World War:

- Chysauster Ancient Village, on the Land’s End Peninsula

- Tintagel Castle, on Cornwall’s north coast

- Restormel Castle, near Bodmin

- Pendennis Castle, overlooking Carrick Roads near Falmouth

Chysauster Ancient Village (pronounced ‘chy-soyster’, with ‘ch’ as in church)

Sylvester’s House. That’s what Chysauster means; ‘chy’ is Cornish for house or home. But whether Sylvester ever lived there and who he was I guess we’ll never know. Because the remains of this Iron Age village date from Romano-British times, some 1800-2000 years ago.

The Romans never really penetrated into Cornwall, apparently. Thus Chysauster, with its unique courtyard houses (found only in Cornwall and the Scilly Isles), is a very important site in the nation’s history. Courtyard houses are found in several locations, but the village at Chysauster is one of the best preserved.

As I walked on to the site I had this feeling that the village had once been a thriving community. I could imagine children playing among the houses, smoke rising from each roof. A busy place.

We spent about an hour walking from one building to the next, fascinated by the layout of each house with its rooms off the central courtyard, and even a backdoor.

Take a look at more photos here. This is the link to English Heritage.

Tintagel Castle

Did King Arthur live here? Did he even exist? Whatever the truth of the myth, Tintagel Castle will forever be linked with his name. It’s certainly an iconic site jutting out into the North Atlantic, battered constantly by winds and storms. It was quite windy on the day of our visit, but thankfully dry.

Did King Arthur live here? Did he even exist? Whatever the truth of the myth, Tintagel Castle will forever be linked with his name. It’s certainly an iconic site jutting out into the North Atlantic, battered constantly by winds and storms. It was quite windy on the day of our visit, but thankfully dry.

Click here to download a phased plan of the castle, which shows its occupation over almost a thousand years.

Geoffrey of Monmouth has a lot to answer for, because much of what we ‘know’ of our history prior to the 12th century is a mixture of fact and fiction that he wrote in his History of the Kings of Britain.

Among the many myths that he conjured up is the tale of King Arthur and his links with Tintagel Castle where, claimed Geoffrey, Arthur was conceived.

Tintagel Castle was once home to a thriving community of more than 300 persons. But since much of its history derives from the so-called Dark Ages (the period between the exodus of the Romans in the 5th century AD and the arrival of the Normans in the 11th). Tintagel Castle island is dotted with the remains of many houses.

Tintagel Castle was once home to a thriving community of more than 300 persons. But since much of its history derives from the so-called Dark Ages (the period between the exodus of the Romans in the 5th century AD and the arrival of the Normans in the 11th). Tintagel Castle island is dotted with the remains of many houses.

We arrived at Tintagel just before 09:30. I wanted to be sure of a parking place knowing that it can become very busy. The castle opened at 10:00, so we took a slow walk down to the entrance, about half a mile, and quite steep in places. We opted for the Land Rover ride (at £2 each) back up to the car park after our visit.

The cafe was just opening, so we enjoyed a quick coffee before registering for our visit, and getting some wise advice about how to tackle the site. There are lots (and I mean lots) of steps at Tintagel, some very steep indeed. The person on the ticket counter advised us to enter the site through the upper entrance (just before 1), and straight into the mainland courtyards (3 and 4) that overlook the main entrance and island courtyard and Great Hall (6).

There is a set of extremely steep steps down the cliff to then cross a bridge and climb into the main ruins. The walk up to the upper entrance and courtyards was certainly gentler than had we visited the main island first then returned to view the courtyards (and climb that set of stairs) as we saw many other visitors doing later one. And by visiting the courtyards first, we had a panorama over the island ruins to get our bearings.

Check out the full album of photographs. It takes about an hour and a half to walk round the ruins and appreciate everything that Tintagel has to offer. The views over the cliffs, north and south down the coast are typical Cornwall, and you’re left wondering how a community managed to survive for so long in this rather desolate spot.

Restormel Castle

Moving forward to the 12th century, Restormel is a Norman castle alongside the River Fowey in Lostwithiel. Its circular shell keep is unusual (the round tower at Windsor Castle is also a shell keep), built on a mound surrounded by a dry (and quite deep) ditch. The ruins are remarkably well preserved, and in addition to wandering through the various rooms at ground level, English Heritage has provided access to the battlements, from which there is a good panoramic view over the surrounding countryside.

You can read a detailed history of Restormel here.

Pendennis Castle

Guarding the approaches to Falmouth, Pendennis Castle has proudly stood on a peninsula overlooking Carrick Roads since the time of Henry VIII in the sixteenth century. And it remained an important fortress right up to the Second World War when guns were installed to combat any threat from German naval vessels.

Across the estuary is another Tudor fortress, St Mawes Castle, a mirror image of Pendennis. During Tudor times, the guns from each could reach half way across the estuary, this protecting Falmouth and its harbor from both sides.

In July 2016 we visited Calshot Castle, that guards the approaches to The Solent near Southampton, and is another of Henry VIII’s coastal fortresses.

Pendennis has a fine collection of cannons inside and also on the battlements, as well as the Second World War guns at Half Moon Battery.

The castle is not just the round tower. There are extensive 18th century barracks and parade grounds enclosed within major earthworks, ramparts constructed during the reign of Elizabeth I.

Check out more photos here.

These are the other four stories in this Cornwall series:

Kernow a’gas dynergh – Welcome to Cornwall (1): The journey south . . . and back

Kernow a’gas dynergh – Welcome to Cornwall (2): Coast to coast

Kernow a’gas dynergh – Welcome to Cornwall (4): An impressive horticultural legacy

Kernow a’gas dynergh – Welcome to Cornwall (5): Magnificent mansions

We chose a small studio cottage, suitable for a couple, just north of Helston on the south coast, a round trip of more than 500 miles (including the side trips to a couple of National Trust properties on the way there and back – see

We chose a small studio cottage, suitable for a couple, just north of Helston on the south coast, a round trip of more than 500 miles (including the side trips to a couple of National Trust properties on the way there and back – see

My son-in-law, Michael, is – like me – a beer aficionado, and keeps a well-stocked cellar of many different beers. It’s wonderful to see how the beer culture has blossomed in the USA, no longer just Budweiser or Coors. I had opportunity to enjoy a variety of beers. Those IPAs are so good, if not a little hoppy sometimes. However, my 2018 favorite was a Czech-style pilsener,

My son-in-law, Michael, is – like me – a beer aficionado, and keeps a well-stocked cellar of many different beers. It’s wonderful to see how the beer culture has blossomed in the USA, no longer just Budweiser or Coors. I had opportunity to enjoy a variety of beers. Those IPAs are so good, if not a little hoppy sometimes. However, my 2018 favorite was a Czech-style pilsener,

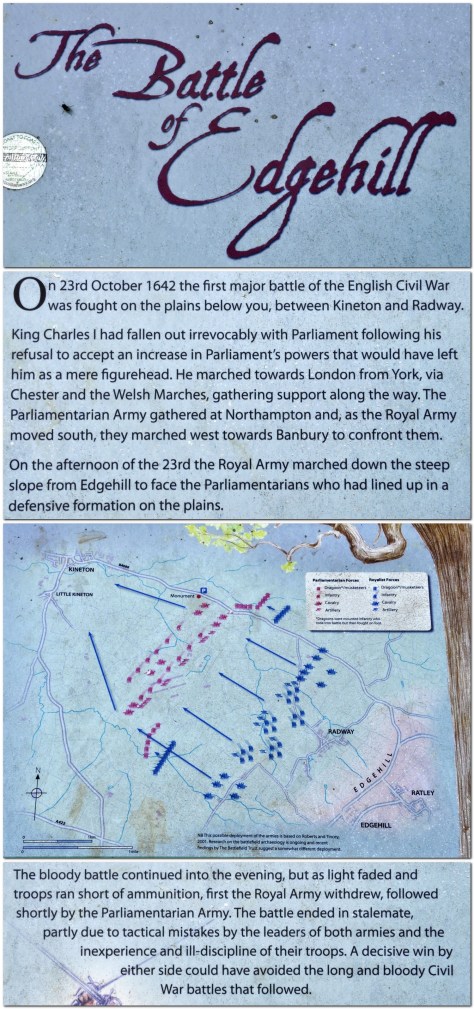

Despite its incredibly bloody outcomes and destructive consequences, the American Civil War, 1861-65 holds a certain fascination. To a large extent, it was the first war to be extensively documented photographically, many of the images coming from the lens of

Despite its incredibly bloody outcomes and destructive consequences, the American Civil War, 1861-65 holds a certain fascination. To a large extent, it was the first war to be extensively documented photographically, many of the images coming from the lens of

takes some getting used to. I now understand that unless it specifically states not to turn, it’s OK to make that turn. Not something we’re used to in the UK. Red means red! And also, having to be aware that if you turn right on a red light, there may be pedestrians crossing as they will have right of way.

takes some getting used to. I now understand that unless it specifically states not to turn, it’s OK to make that turn. Not something we’re used to in the UK. Red means red! And also, having to be aware that if you turn right on a red light, there may be pedestrians crossing as they will have right of way.

I’m almost 70, yet, when buying a couple of cases of beer at Target in St Paul recently, I was asked for my ID! Fortunately the lady at the checkout was from Scandinavia (and had lived in the UK for several years) so recognized my UK photo driving licence. She told me that normally it would have to be a US or Canadian driving licence or passport. Good grief, 70 years old and having to present a passport just to buy a beer! And then there was $2.36 sales tax to add to the offer of $25 for two cases that had attracted my attention.

I’m almost 70, yet, when buying a couple of cases of beer at Target in St Paul recently, I was asked for my ID! Fortunately the lady at the checkout was from Scandinavia (and had lived in the UK for several years) so recognized my UK photo driving licence. She told me that normally it would have to be a US or Canadian driving licence or passport. Good grief, 70 years old and having to present a passport just to buy a beer! And then there was $2.36 sales tax to add to the offer of $25 for two cases that had attracted my attention.

Just north of the state line we took a short detour to

Just north of the state line we took a short detour to

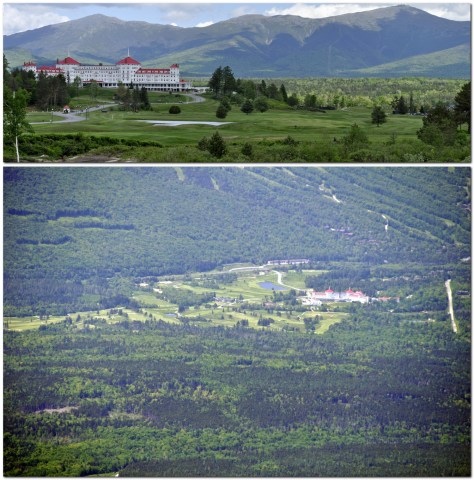

There was a glorious view south from Whitcomb Summit, and some miles further on, just short of North Adams, there is a spectacular view north into southern Vermont, reminding us of the views we saw when exploring the

There was a glorious view south from Whitcomb Summit, and some miles further on, just short of North Adams, there is a spectacular view north into southern Vermont, reminding us of the views we saw when exploring the

It’s not my intention here to provide a detailed history of Rievaulx Abbey. English Heritage owns and manages the site, and a detailed history of Rievaulx’s founding and growth can be found on its

It’s not my intention here to provide a detailed history of Rievaulx Abbey. English Heritage owns and manages the site, and a detailed history of Rievaulx’s founding and growth can be found on its

So, with much more inclement weather forecast, Steph and I decided that we’d better take advantage of yesterday’s decent weather and head out for a walk, and visit yet another National Trust property:

So, with much more inclement weather forecast, Steph and I decided that we’d better take advantage of yesterday’s decent weather and head out for a walk, and visit yet another National Trust property:

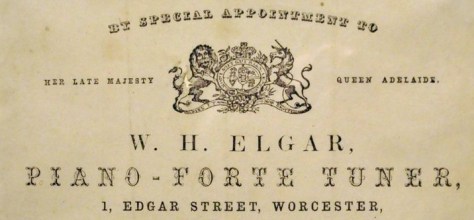

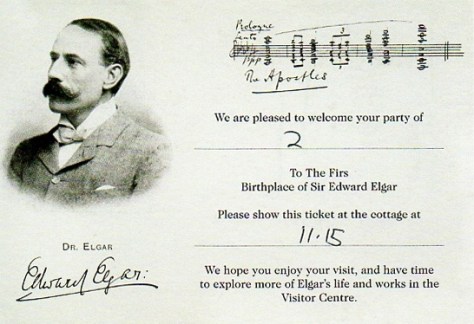

Elgar was born in June 1857 in a small cottage, The Firs, in the village of

Elgar was born in June 1857 in a small cottage, The Firs, in the village of