It was World Book Day yesterday, to promote reading for pleasure, offering every child and young person the opportunity to have a book of their own.

It was World Book Day yesterday, to promote reading for pleasure, offering every child and young person the opportunity to have a book of their own.

The rationale behind World Book Day is that ‘Reading for pleasure is the single biggest indicator of a child’s future success – more than their family circumstances, their parents’ educational background or their income’.

And, the BBC announced that it was reviving its 500 Words story competition for children.

There are so many people writing wonderfully for children nowadays. I can’t say that was the case when I was growing up in the 1950s. No Harry Potter then. No Roald Dahl either. But there was an author who, in her day, was just as popular as JK Rowling, and remains so.

Born in November 1948, I started school around September 1953 just before my fifth birthday, or maybe in the following January.

Born in November 1948, I started school around September 1953 just before my fifth birthday, or maybe in the following January.

My first school was Mossley Church of England primary school just south of Congleton in Cheshire. I was seven in 1956 when we moved to Leek, 12 miles southeast of Congleton and I joined St Mary’s Roman Catholic primary. I must have been reading quite satisfactorily by then as I don’t recall any of the teachers commenting negatively on my reading ability. Funnily enough I don’t have any memories of my parents reading to me, although I’m sure they must have.

Like most other children in the 1950s my first reading primers were the Dick and Dora books (or similar), with their dog Nip and cat Fluff. I haven’t yet found information about the publishers or how many primers were produced. Here’s an example of what we worked with.

They were used to teach reading using the whole-word or look-say method (also called sight reading). There were equivalents in the USA (Dick and Jane) and in Australia, the Dick and Dora books were still being used as late as 1970.

The other books that figured significantly in my early reading were the Ladybird Books, first published over 100 years ago and still popular today. So many to choose from. They were also a favorite of my daughters in the 1980s.

They have been referred to as ‘literary time capsules‘.

I joined the public library in Leek, and it was then that I first encountered the stories by prolific author Enid Blyton.

Born in 1897, and publishing her first book in 1922, Enid Blyton went on to write around 700 books and about 2000 short stories as well as poems and magazine articles right up to her death in 1968.

Born in 1897, and publishing her first book in 1922, Enid Blyton went on to write around 700 books and about 2000 short stories as well as poems and magazine articles right up to her death in 1968.

Among her many successes were the Toyland stories featuring Noddy and Big Ears, and a host of other characters, some of which like Golliwog are no longer considered acceptable. These stories still remain popular with young children, and even made into cartoons that can be watched on YouTube.

Among her many successes were the Toyland stories featuring Noddy and Big Ears, and a host of other characters, some of which like Golliwog are no longer considered acceptable. These stories still remain popular with young children, and even made into cartoons that can be watched on YouTube.

But it was Blyton’s stories for older children that gripped me: the Famous Five series (21 books between 1942 and 1963), the Secret Seven (15 books between 1949 and 1963), and the Adventure series (8 books between 1944 and 1955).

Each of these books had a group of child characters who had exciting adventures, mainly during their school holidays. Treasure, possible crime, even espionage. And, in the ‘Adventure’ series, a cockatoo named Kiki.

Recently, there has been an initiative to revise some of the language and terms used in her books, to make them more acceptable to 21st century children. The same is happening to the works of Roald Dahl, to much controversy. Besides these there were my weekly Swift comic (and my elder brothers’ Eagle) and the Annuals published around Christmas time.

In addition to the Blyton stories, there is one that has remained firmly in my mind. And although I don’t remember the whole of the narrative in detail, it still holds a special place in my list of children’s book.

Written by Denys Watkins-Pitchford (under the pseudonym ‘BB’) in 1955, The Forest of Boland Light Railway tells the tale of a community of gnomes who build a steam locomotive to transport miners to work, and return with larger quantities of gold. Everything goes well until a group of wicked goblins decide to steal the train and put the railway out of business.

If you ever get the chance to find a copy (that are selling on secondhand books websites for a small fortune) I’m sure you would enjoy it even as an adult.

Watkins-Pitchford, a well-known naturalist, published 60 books between 1922 and 1990, not all of them children’s books. And I never came across one, The Little Grey Men, for which he won the 1942 Carnegie Medal for British children’s books.

Anyway, it’s interesting (for me at least) how an event like World Book Day 2023 stirred up so many memories from almost 70 years ago.

I spend much of my free time nowadays with my nose inside an book. A few years I came across the works of Charles Dickens in a serious way, having despised them as compulsory reading while at school. What a revelation they turned out to be.

2020 started where 2019 had ended – half way through George Eliot’s Middlemarch (published 1871-1872). That was a bit of a struggle in places, but I finally got there. And, on reflection, I did quite enjoy it.

2020 started where 2019 had ended – half way through George Eliot’s Middlemarch (published 1871-1872). That was a bit of a struggle in places, but I finally got there. And, on reflection, I did quite enjoy it.

That got me into

That got me into

During the pandemic I had expected to read more. But by the beginning of May I’d run out of steam. So it took me almost two months to finish re-reading Adrian Goldsworthy’s Caesar. It was fascinating to understand something about perhaps the greatest Roman (often based on his own words, as he was a prolific writer, ever keen to make sure his place in history was secure). I bought this book around 2007, and first read it while I was working in the Philippines.

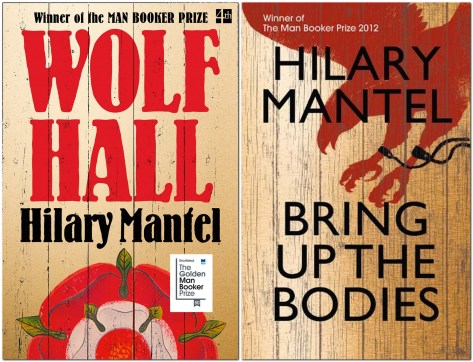

During the pandemic I had expected to read more. But by the beginning of May I’d run out of steam. So it took me almost two months to finish re-reading Adrian Goldsworthy’s Caesar. It was fascinating to understand something about perhaps the greatest Roman (often based on his own words, as he was a prolific writer, ever keen to make sure his place in history was secure). I bought this book around 2007, and first read it while I was working in the Philippines. Anyway, I eventually finished Tess and on 30 September the sale of our house went through and we moved north. Settling into our new home (a rental for six months until we found a house to buy – which we have), we registered with the local North Tyneside library, just ten minutes from home. And there, on the new books shelf was Hilary Mantel’s magnum opus, and the last in her Thomas Cromwell trilogy,

Anyway, I eventually finished Tess and on 30 September the sale of our house went through and we moved north. Settling into our new home (a rental for six months until we found a house to buy – which we have), we registered with the local North Tyneside library, just ten minutes from home. And there, on the new books shelf was Hilary Mantel’s magnum opus, and the last in her Thomas Cromwell trilogy,  I finished The Mirror & the Light just before we went into our second national lockdown at the beginning of November, so I hurriedly returned it to the library, and searched for a couple of local histories. The first of these was Tyneside – A History of Newcastle and Gateshead from Earliest Times, by Alistair Moffat and George Rosie, published in 2005 (and made into a TV documentary, which I haven’t seen).

I finished The Mirror & the Light just before we went into our second national lockdown at the beginning of November, so I hurriedly returned it to the library, and searched for a couple of local histories. The first of these was Tyneside – A History of Newcastle and Gateshead from Earliest Times, by Alistair Moffat and George Rosie, published in 2005 (and made into a TV documentary, which I haven’t seen). Next, I picked up A Man Most Driven, by Peter Firstbrook, about ‘Captain John Smith, Pocahontas and the Founding of America’ in the early seventeenth century. Now, I’d heard about

Next, I picked up A Man Most Driven, by Peter Firstbrook, about ‘Captain John Smith, Pocahontas and the Founding of America’ in the early seventeenth century. Now, I’d heard about  I then turned my attention to local Newcastle history once again, by former Northumberland county court judge and one-time MP for Newcastle Central from 1945-1951), Lyall Wilkes called Tyneside Portraits. It’s a short anthology of eight men who contributed to the artistic and cultural life of Newcastle since the seventeenth century, as well as its physical appearance through the buildings they designed and built. Among them was

I then turned my attention to local Newcastle history once again, by former Northumberland county court judge and one-time MP for Newcastle Central from 1945-1951), Lyall Wilkes called Tyneside Portraits. It’s a short anthology of eight men who contributed to the artistic and cultural life of Newcastle since the seventeenth century, as well as its physical appearance through the buildings they designed and built. Among them was

This was the third and last book I had borrowed from the local library before the most recent pandemic lockdown and then Tier 3 restrictions locally. The library has not yet re-opened and I was unable to replace these books. So it was back to the Kindle and a touch of Rudyard Kipling once again:

This was the third and last book I had borrowed from the local library before the most recent pandemic lockdown and then Tier 3 restrictions locally. The library has not yet re-opened and I was unable to replace these books. So it was back to the Kindle and a touch of Rudyard Kipling once again: