Although I spent most of my career working on potatoes and rice, my first interest was pulse crops or grain legumes. In fact the first pulse that I studied was the lentil (Lens culinaris Medik.) when I was an MSc student at the University of Birmingham from 1970-1971.

So why the interest in pulses?

It was surely the influence of one of my mentors, Dr Joe Smartt (right) at the University of Southampton where I was awarded my BSc in Environmental Botany and Geography in 1970. A geneticist who had studied groundnuts in Africa and at Southampton was working on Phaseolus beans, Joe taught a second year genetics course, and two in the third or final year, on plant breeding and plant speciation.

It was surely the influence of one of my mentors, Dr Joe Smartt (right) at the University of Southampton where I was awarded my BSc in Environmental Botany and Geography in 1970. A geneticist who had studied groundnuts in Africa and at Southampton was working on Phaseolus beans, Joe taught a second year genetics course, and two in the third or final year, on plant breeding and plant speciation.

He published two seminal texts on pulses in 1976 and 1990.

It was Joe who ignited my interest in plant genetic resources, and encouraged me to apply for a place on the one year MSc course at Birmingham on Conservation and Utilization of Plant Genetic Resources (CUPGR). The course had been launched by the head of the Department of Botany, potato expert, and genetic resources pioneer, Professor Jack Hawkes, with the first intake of students commencing their studies in September 1969. I landed in Birmingham a year later.

My three year undergraduate course at Southampton was a stroll in the park compared to the intensity of that one year MSc course. We had eight months of lectures and practical classes, followed by written examinations at the end of May. Each student also had to complete a piece of independent but supervised research, and present a dissertation for examination in September. In order to take full advantage of the summer months, planning and some initial research began much earlier. First of all for most of us, we had to decide on a topic that was feasible and doable in the allotted time, and assemble the necessary seed samples ready for planting at the most appropriate date.

Almost immediately I decided on three points. First, I wanted to run a project with a taxonomy/natural variation theme. Second, I wanted—if feasible—to work on a pulse species. And finally (which I decided quite quickly after arriving in Birmingham) I wanted to work with Dr Trevor Williams (right) who delivered a brilliant series of lectures on variation in natural populations, among others.

Trevor and I thumbed our way through the Leguminosae (now Fabaceae) section of Flora Europaea, until we came upon the entry for Lens, and the topic for my project leapt off the page: Lens culinaris Medik. Lentil. Origin unknown.

My project had two components:

- An analysis of variation in the then five species of lentil (one cultivated, the others wild species; the taxonomy has changed subsequently) from herbarium specimens borrowed from several herbaria in Europe. I also spent a week in the Herbarium at Kew Gardens in London taking measurements from their complete set of lentil specimens.

- A study of variation in Lens culinaris from living plants, with seeds obtained from Russia (the Vavilov Institute in St Petersburg), from the (then) East German genebank in Gatersleben, and from the agricultural research institute in Madrid.

With the guidance of another member of the Botany department staff, Dr Herb Kordan, I made chromosome preparations and counts of all the Lens culinaris samples I’d obtained, confirming they were all diploid with 2n=2x=14 chromosomes. In the process, we developed a simple but effective technique for making chromosome squash preparations, and this led to my first ever publication in 1972. Just click on the title below (and others in this post) to read the full text.

In September 1971, I submitted my dissertation, Studies in the genus Lens Miller with special reference to Lens culinaris Medik. (which was examined by Professor Norman Simmonds who was the course External Examiner), and the degree was awarded.

I proposed that the wild progenitor of the cultivated lentil was Lens orientalis (Boiss.) Hand.-Mazz., a conclusion reached independently by Israeli botanist Daniel Zohary in a paper published the following year.

In 1971-1972, Carmen Kilner (née Sánchez) continued with the lentil studies at Birmingham, leading to a publication in SABRAO Journal in 1974. Our paper added further evidence to confirm the status of Lens orientalis.

When I began my lentil project, I had ideas to extend it to a PhD were the funding available. However, in February 1971 Jack Hawkes had just returned from a potato collecting mission to Bolivia, and told me about an exciting opportunity to spend a year in Peru at the newly-founded International Potato Center (CIP), from September that same year. My departure to Peru was delayed until January 1973, so I began a PhD on potatoes with Jack in the meantime. And with that move to potatoes, I assumed that any future work with pulses was more or less ruled out. However, from April 1981 I was appointed Lecturer in Plant Biology at Birmingham, and needed to develop a number of research areas. Would pulses figure in those plans?

While I wanted to continue projects on potatoes at Birmingham, I also decided to return partially to my first interest: pulses. And while I never had major grants in this area, I did supervise graduate students for MSc and PhD degrees who worked on a range of grain and forage legume/pulse species. Here I highlight the work of three students. There may have been more who worked on pulses, but after four decades I can’t remember those details.

Almost immediately after returning to Birmingham, I discovered (by looking through Flora Europaea once again) that the origin of the grasspea, Lathyrus sativus, was unknown. The grasspea is a distant relative of the ornamental sweetpea, Lathyrus odoratus, one of my favorite flowers since I was a small boy. My grandfather used to grow a multitude of sweetpeas in his cottage garden in Derbyshire. Anyway, I set about assembling a large collection of seed samples (or accessions) of grasspea and wild Lathyrus species from agricultural centers and botanic gardens worldwide.

Almost immediately after returning to Birmingham, I discovered (by looking through Flora Europaea once again) that the origin of the grasspea, Lathyrus sativus, was unknown. The grasspea is a distant relative of the ornamental sweetpea, Lathyrus odoratus, one of my favorite flowers since I was a small boy. My grandfather used to grow a multitude of sweetpeas in his cottage garden in Derbyshire. Anyway, I set about assembling a large collection of seed samples (or accessions) of grasspea and wild Lathyrus species from agricultural centers and botanic gardens worldwide.

The academic year September 1981-September 1982 was my first full year at Birmingham. Among the CUPGR intake was a Malaysian student, Abdul bin Ghani Yunus (right), who asked me to supervise his MSc research project. I persuaded him to tackle a study of variation in the grasspea and its wild relatives, much along the lines I had approached lentil a decade earlier.

The academic year September 1981-September 1982 was my first full year at Birmingham. Among the CUPGR intake was a Malaysian student, Abdul bin Ghani Yunus (right), who asked me to supervise his MSc research project. I persuaded him to tackle a study of variation in the grasspea and its wild relatives, much along the lines I had approached lentil a decade earlier.

We published this paper in 1984, and I guess it heralded what would become, a several decades later, an international collaborative effort to improve the grasspea and make it safer for human consumption.

Ghani returned to Malaysia, and I didn’t hear from him for several years. Then, in 1987, he contacted me to say he’d secured a Malaysian government grant to study for his PhD and would like to return to Birmingham. But to work on a tropical species, the name of which I cannot remember.

I persuaded him that would not really be feasible in Birmingham as we didn’t have the glasshouse space available, and it would be hit or miss whether we would be able to grow it successfully. I suggested it would be better to carry on his Lathyrus work from where he left off. And that’s what he did, successfully submitting his thesis in 1990 from which these papers were published.

Among the 1986 CUPGR intake was a student from Mexico, José Andrade-Aguilar (right) who was keen to attempt a pre-breeding study in Phaseolus beans, specifically trying to cross the tepary bean, Phaseolus acutifolius A. Gray with the common bean, Phaseolus vulgaris L.

José published two papers from his dissertation.

This next paper (for which I no longer have a copy) described how pollinations in Phaseolus species could be made more successful.

Then, in 1987, a student from Spain, Javier Francisco-Ortega (right, actually from Tenerife in the Canary Islands) joined the course, and he and I worked closely on his MSc and PhD projects until I left Birmingham to join IRRI in the Philippines in July 1991.

Javier was an extraordinary student: hard-working, focused, and very productive. After completing his PhD in 1992, he took two postdoctoral fellowships in the USA (at Ohio State University and the University of Texas at Austin) before joining the faculty of the Department of Biological Sciences at Florida International University in 1999, where he has been Professor in Plant Molecular Systematics since 2012.

For his 1988 MSc dissertation, Javier studied the variation in Lathyrus pratensis L., using multivariate analysis, and publishing this paper some years later.

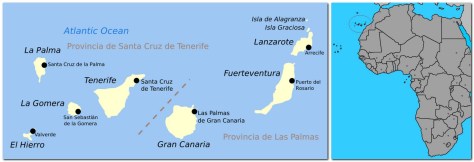

Then, having successfully completed his MSc, and being awarded a second Spanish government scholarship, Javier began a PhD project to study the ecogeographical variation in an endemic forage legume from the Canary Islands, Chamaecytisus proliferus (L. fil.) Link., known locally as tagasaste or escobón, depending whether it is cultivated or a purely wild type.

With a special grant from the International Board for Plant Genetic Resources (IBPGR, now Bioversity International) in Rome, Javier returned to the Canary Islands in the summer of 1989 to survey populations and collect seeds from as many provenances as possible across all the islands, and I joined him there for several weeks.

Collecting escobón (Chamaecytisus proliferus) in Tenerife in 1989

After I left Birmingham, my colleague Professor Brian Ford-Lloyd took over supervision of Javier’s research, seeing it through to completion in 1992.

Together we published these papers from his research on tagasaste and escobón.

Once I was in the Philippines, I forgot completely about legume species, apart from contributing to any of the papers that were published after I’d left Birmingham.

One aspect that is particularly gratifying however is seeing the work Ghani Yunus and I did on Lathyrus still being cited in the literature as efforts are scaled up to improve grasspea lines.