Well, if I count the visit to Plas Newydd on the southern shore of Anglesey, on the way to Holyhead to catch the ferry over to Ireland, Steph and I visited twelve National Trust properties in eight days.

We have wanted to visit Northern Ireland for many years, but until now never really had the opportunity, or we felt that the security situation didn’t make for a comfortable visit. All that has changed. Now retired, we have time on our hands. ‘The Troubles‘ are a thing of the past (fortunately), and the Peace Process in Northern Ireland has transformed the opportunities for that part of the United Kingdom.

Being members of the National Trust, and knowing that there were some splendid houses to see over in Northern Ireland, as well as some Trust-owned landscapes such as the spectacular Giant’s Causeway on the north Antrim coast, this was just the incentive we needed to decide, once and for all, to cross over to the island of Ireland again. We have visited south of the border several times. I first went to Co. Clare in 1968, and Steph and I had holidays there traveling around in 1992 and 1996.

Planning the trip – finding somewhere to stay

For a number of recent holidays, I have used booking.com to search for hotels when I was planning our road trips across the USA. So I used this company this time round when looking for an overnight stay in Holyhead, convenient for the ferry to Ireland early the next morning.

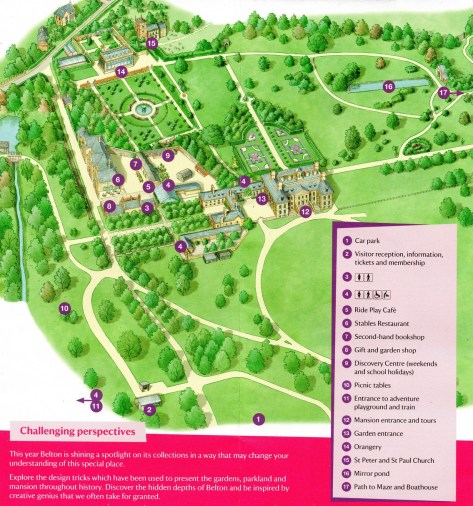

In Northern Ireland we were looking for somewhere central from where it would be a relatively easy drive each day to any part because the National Trust properties we wanted to visit were scattered all over (as shown in the map above). After reading various online reviews (are they always reliable?), and looking for value for money, we chose The Drummeny Guest House in Ardboe, Co. Tyrone (Mid-Ulster council district), on the west shore of Lough Neagh.

Me and Tina Quinn on the morning of our departure from The Drumenny Guest House

What a find! Our hosts, Tina and Damien Quinn, were the best. What a friendly welcome, and hospitality like you would never believe. The reviews on booking.com were all very positive. Were they accurate? Absolutely! In fact, our experience was even better than previous reviewers had described. Such a breakfast (full Irish), and lots of other extras that Tina provided. In fact, staying with Tina and Damien it felt as though we were staying with family, and a week at The Drumenny was better than we ever anticipated. So, if you ever contemplate a Northern Ireland holiday, there’s only one place to head for: The Drumenny Guest House in Ardboe. You won’t be disappointed.

Less than a mile away there’s a good restaurant, The Tilley Lamp, that serves good, simple food, and lots of it. Very convenient.

Day 1: 8 Sep — home to Holyhead, via Plas Newydd (168 miles; map)

Our Northern Ireland trip started just after 09:15, and because of major road works (and almost certain traffic congestion) we decided to travel northwest from Bromsgrove via Kidderminster and Bridgnorth, before joining the A5 south of Shrewsbury. We then continued on the A5 through Snowdonia, and over the Menai Strait to Plas Newydd House and Gardens, just a few miles west of Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantysiliogogogoch.

Home to the Marquesses of Anglesey (descendants of the 1st, who as the Earl of Uxbridge, served alongside the Duke of Wellington at the Battle of Waterloo, and had his leg blown off by a cannonball), Plas Newydd stands on the shore of the Menai Strait that separates Anglesey from mainland Wales.

Day 2: 9 Sep — Dublin to Ardboe, calling at Derrymore House near Newry, and Ardress House (120 miles), Co. Armagh

Our Stena Line Superfast X ferry arrived to Dublin Port on time, just after noon, and we quickly headed north on the M1, crossing into Northern Ireland just south of Newry in Co. Armagh.

Derrymore House lies a few miles west of the A1, and is open for just five afternoons a year. That was a piece of luck that we happened to pass by on one of those days. It’s a late 18th century thatched cottage. The ‘Treaty Room’ is the only room open to the public, and the 1800 Act of Union uniting the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland is supposed to have been drafted there.

Further north, and the route to Ardboe, we also visited Ardress House, built in the 17th century, and embellished in the 18th. It has a traditional farmyard.

We arrived to our guesthouse around 18:00, and enjoyed a meal out that evening at The Tilley Lamp. The best pork chops I’ve ever tasted.

Day 3: 10 Sep — Ardboe Cross, Co. Tyrone, Springhill House, Co. Londonderry and The Argory, Co. Armagh (53 miles)

Sunday morning. We decided to briefly explore the Lough Neagh shore near Arboe, and see one of Ireland’s national monuments, the Ardboe Cross.

Springhill House is a typical 17th ‘Plantation‘ house, showing the history of ten generations of the Lenox-Conyngham family.

The Argory is just 20 miles south of Springhill, and was built in the 1820s and was the home of the MacGeough Bond family, and has remained unchanged since 1900. It has magnificent interiors, particularly the cantilevered staircase.

Day 4: 11 Sep — Florence Court and Crom Castle, Co. Fermanagh (169 miles)

Florence Court is the furthest west of all of the National Trust’s properties, a few miles southwest of Enniskillen in Co. Fermangh. It was the home of the Earls of Enniskillen, and was built in the 18th century. There are beautiful views of the nearby mountains from the front of the house. Inside, where photography is not permitted, the walls and ceilings have some of the finest stucco plaster work I have seen. In 1955 there was a disastrous fire and it’s credit to the National Trust how well they accomplished the refurbishment. Remarkably many of the precious items in the house were saved.

On our route back to Ardboe, we diverted to make a quick visit to the ruins of Crom Castle, on the banks of Upper Lough Erne. There was time for a walk to the ruins from the Visitor Centre before it closed for the day, and approaching showers drenched us. There were some lovely views over the lough to Creighton Tower.

We also saw how convoluted the border is between Northern Ireland and the Republic. Sorting that out during the Brexit negotiations will be a challenge, nightmare even, and so unnecessary. It is an invisible border, and hopefully obstacles will not be put in place by this incompetent Conservative government that will undermine the economic and social progress that Northern Ireland has made in recent years. This story on the BBC website (20 September) has a video of the very road we took back to Ardboe between the counties of Fermanagh (Northern Ireland) and Monaghan (Republic).

Day 5: 12 Sep — Giant’s Causeway and the Antrim coast, Co. Antrim (162 miles)

The Giant’s Causeway has long been on my Bucket List of attractions to visit. And we weren’t disappointed. We had carefully monitored the weather forecasts and chose what we hoped would be the best day of the week. In general it was. The drive north from Ardboe took just under 2 hours. We passed through the small town of Bellaghy, Co. Londonderry, burial site of Nobel Literature Laureate Seamus Heaney. I wish we had stopped.

Although it was not yet 10:30 when we reached the Visitors’ Centre at the Giant’s Causeway, it was already very busy, and just got busier over the three hours we stayed there. There were visitors from all over the world – particularly from China.

It’s a walk of more than a mile down the cliff to the actual Causeway, so we took a leisurely stroll there. But we did take advanatge of the free bus ride (as National Trust members) to go back up the cliff road.

We then headed east along the north Antrim coast, and stopped for a picnic at the Rope Bridge car park where a torrential downpour spoiled the view and prompted us to move on rather than have a wander around. Then we headed down the east coast on a road that hugs the bottom of cliffs along the seashore, before reaching Larne and then heading west around the top of Lough Neagh and home to The Drumenny.

Day 6: 13 Sep — Mount Stewart, Co. Down (127 miles)

On the northeast shore of Strangford Lough, just south of Newtownards, the Mount Stewart estate was purchased in the mid-18th century, and became the home of the Marquesses of Londonderry when the current house was built at the beginning of the 19th century. It has a beautiful formal garden, mostly the work of Lady Edith, wife of the 7th Marquess.

Day 7: 14 Sep — Castle Coole, Co. Fermanagh, Donegal (Republic of Ireland), and the Sperrin Mountains in Co. Londonderry and Co. Tyrone (200 miles)

On Day 7, we headed west once again to visit Castle Coole, situated just outside Enniskillen. We were not able to visit there when we had travelled west on Day 4, as the property had been closed for a special BBC Proms in the Park event.

Castle Coole was built by the 1st Earl Belmore between 1789 and 1797. It’s mostly the design of famous English architect James Wyatt, who also designed much of the interior and even the furniture. Photography is not permitted inside, and I’m unable to show you some of the splendours of this house, particularly the Saloon, which must rank as one of the finest examples of its kind among any of the stately homes in this country. The current Earl Belmore resides in a cottage on the estate.

Leaving Castle Coole, we headed west into the Republic, turning north at Donegal and crossing back into Northern Ireland at Strabane. We decided to cross the Sperrin Mountains, and had the weather been better (much of the journey north of Donegal was in torrential rain), I could have taken some nice photos. But we did have one surprise. Having taken one wrong turn too many when road signs petered out, we stumbled across a Bronze Age site of stone circles and cairns, at Beaghmore. It had stopped raining, everywhere was sparkling in the evening sun, and we enjoyed a half hour walk around the site.

Given the sunshine and showers, conditions just right for the appearance of rainbows. We saw ten throughout the day, some double.

Day 8: 15 Sep — Rowallane Garden and Castle Ward, Co. Down (136 miles)

Just south of Saintfield alongside the A7, Rowallane Garden is a haven of tranquility, about 50 acres, created in the mid-19th century by the Revd. John Moore and his nephew Hugh Armytage Moore. It’s also the headquarters of the National Trust in Northern Ireland.

Then we headed the further 16 miles southeast to Castle Ward on the tip of Strangford Lough. It’s an extraordinary building: Neo-Classical Gothic! The two architectural styles are reflected on the front and rear of the building, and mirrored inside, because, it is said, the 1st Viscount Bangor and his wife could not agree.

The Ward family, originally from Cheshire, settled here in the late 16th century, and there is an old castle on the estate – used in the hit HBO TV series Game of Thrones.

Steph (L) and Clare at Kilmacurragh Botanic Gardens

Day 9: 16 Sep — Arboe, Co. Tyrone to Rathdrum, Co. Wicklow (224 miles)

We travelled south into the Republic, taking a winding route through Co. Monaghan, Cavan, Longford, Westmeath, Offaly, Kildare and Wicklow to spend the night with old IRRI friends Paul and Clare O’Nolan. Paul had been the IT Manager at IRRI; Clare was my scuba dive buddy (video) for several years. On the evening of our arrival, Clare took us on a tour of the Kilmacurragh Botanic Gardens close to where they live on the edge of the Wicklow Mountains.

Day 10: 17 Sep — Rathdrum to Dublin, Holyhead to home (235 miles)

We left the O’Nolans just before noon, and headed north around the M50 to Dublin Port for our 15:10 Stena Superfast X ferry to Holyhead. We disembarked at exactly 19:00, and the drive home to Bromsgrove took four hours. Fortunately the roads were quite quiet and we made reasonably good progress until we were less than 20 miles from home when we were slowed down by major roadworks on the M5 motorway.

Ten days away, 1594 miles covered, twelve National Trust properties visited, seven enormous Irish breakfasts enjoyed. Northern Ireland was everything we hoped for: beautiful landscapes and friendly people. We had delayed our visit there for too long. And the National Trust was our excuse, if one was needed, to make the effort to visit.

All in all, ten days well spent! Here are the detailed posts for the properties:

after a recent visit to the National Trust’s Castle Ward, on the shore of Strangford Lough in Co. Down, Northern Ireland (map). It was built in the 1760s for Bernard Ward, 1st Viscount Bangor. However, the Ward family (originally from Cheshire) owned the estate since the 16th century, and an Old Castle (from about 1590) still stands north of the house.

after a recent visit to the National Trust’s Castle Ward, on the shore of Strangford Lough in Co. Down, Northern Ireland (map). It was built in the 1760s for Bernard Ward, 1st Viscount Bangor. However, the Ward family (originally from Cheshire) owned the estate since the 16th century, and an Old Castle (from about 1590) still stands north of the house. Ward’s son Nicholas succeeded as the 2nd Viscount, but having been declared insane, he died in 1827, unmarried and childless. The title passed to his nephew Edward. The current Viscount Bangor, the 8th, lives in London with his wife, Royal biographer Sarah Bradford, but they have an apartment at Castle Ward for their use. Castle Ward passed to the National Trust after 1950 when the 6th Viscount died, and the estate was accepted in lieu of death duties.

Ward’s son Nicholas succeeded as the 2nd Viscount, but having been declared insane, he died in 1827, unmarried and childless. The title passed to his nephew Edward. The current Viscount Bangor, the 8th, lives in London with his wife, Royal biographer Sarah Bradford, but they have an apartment at Castle Ward for their use. Castle Ward passed to the National Trust after 1950 when the 6th Viscount died, and the estate was accepted in lieu of death duties.

But there is one place, much closer to home, that I wanted to see as long as I can remember. And that place is the

But there is one place, much closer to home, that I wanted to see as long as I can remember. And that place is the

But, as we reached the end of the footpath, we encountered the important ‘Sudbury’ fact. Occupied by the same

But, as we reached the end of the footpath, we encountered the important ‘Sudbury’ fact. Occupied by the same