I’m not sure why or precisely when I developed an interest in the American Civil War. A devastating war (the bloodiest in American history¹), a continent away, with which we had no family connections that I’m aware of, although any on the Irish side of my family who emigrated to the United States in the 1840s and subsequently (as a consequence of the Irish Potato Famine) may well have become involved in the fighting. I just don’t know.

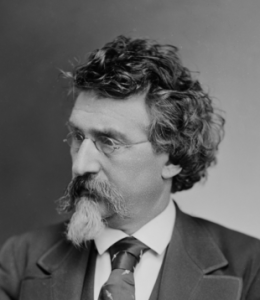

In my early teens, I saw an exhibition of photographs of the Civil War by celebrated American photographer Matthew Brady (right, taken in 1875). Perhaps he was the first photojournalist. And while there are images from earlier wars (such as the Crimean War, from October 1853 to March 1856), I guess the American Civil War was the first to be documented so extensively in this medium.

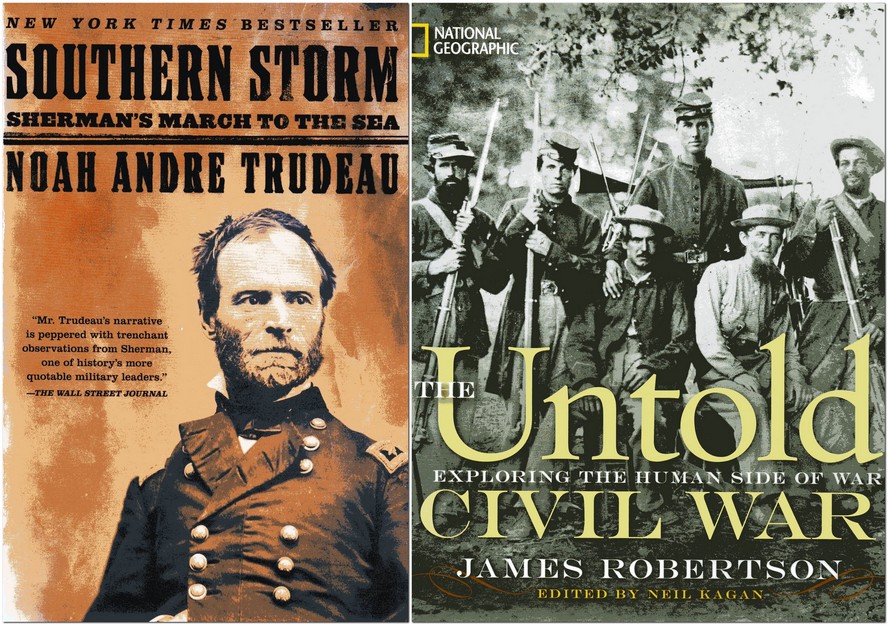

These are just a few archival images that illustrate the National Geographic’s The Untold Civil War, by James Robertson, published in 2011.

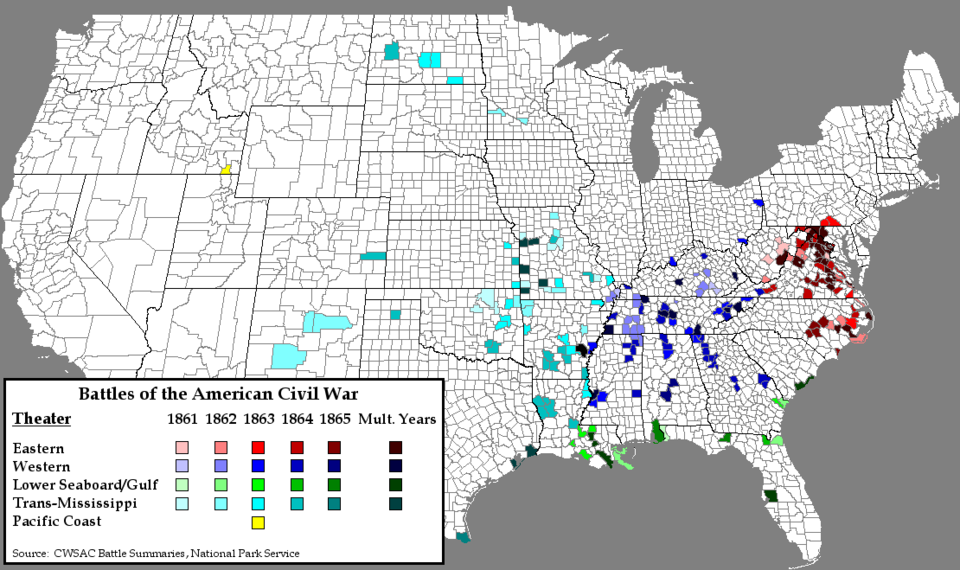

Also, another aspect that caught my attention was the role that the railways played in moving troops and materiel in the various theaters where the war was contested. Again, this was probably a first in terms of the extensive and critical role of railways in any conflict. And the wireless of course, which permitted ‘rapid’ communications about the state of the conflict, provided the lines hadn’t been cut. Like the railways, the lines were frequently targeted.

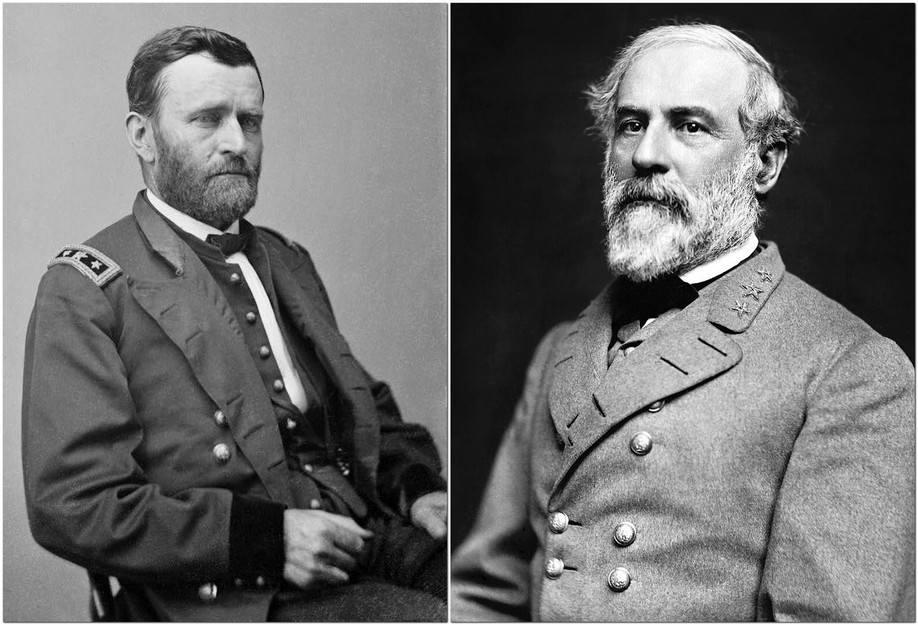

A war that ended 160 years ago, but started on 12 April 1861 when Confederate forces bombarded Fort Sumter (in South Carolina), and which ended to all intents and purposes almost exactly four years later on 9 April 1865 when Confederate General Robert E Lee (right below) surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia to Union General Ulysses S Grant (left) at Appomattox Courthouse in Virginia.

On 18 December 1865, the 13th Amendment to the US Constitution was proclaimed, abolishing slavery and involuntary servitude, once and for all. And with it the root cause for secession and war four years earlier. But, as we know, the abolition of slavery and emancipation of slaves did not correct the ingrained racism that did not die away and continues to this day, despite legislation conferring civil rights and the like.

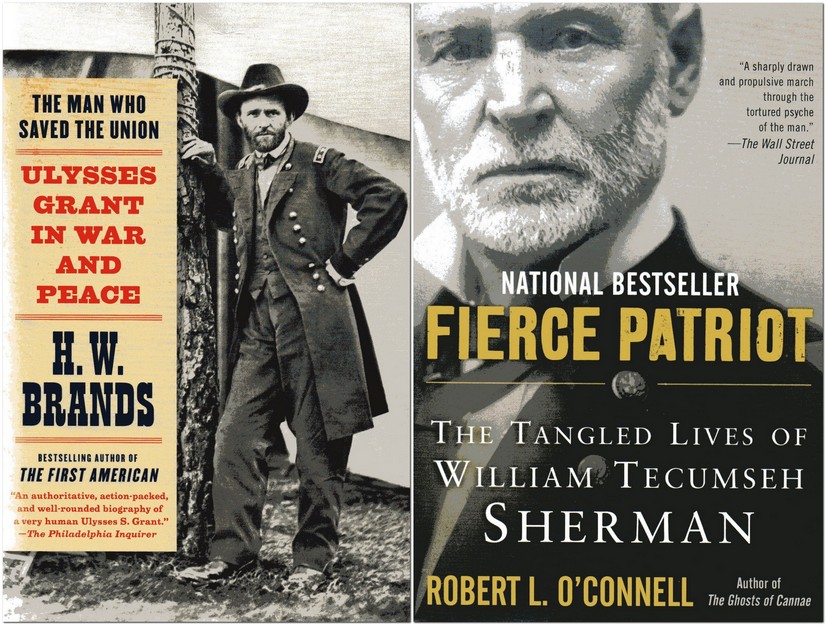

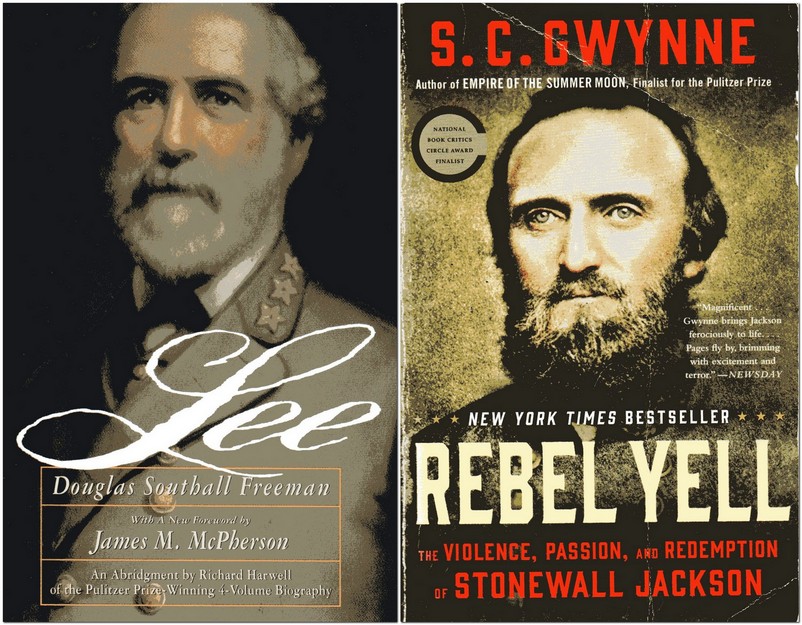

Over the past decade I purchased (from Half Price Books in St Paul) several books² (accounts and biographies) about the war, while visiting family in Minnesota.

And it was one of these, April 1865: The Month that Saved America (first published in 2001) by acclaimed author and historian Jay Winik that I decided to read for a second time, and took it with me on our latest trip to Minnesota in May.

And it was one of these, April 1865: The Month that Saved America (first published in 2001) by acclaimed author and historian Jay Winik that I decided to read for a second time, and took it with me on our latest trip to Minnesota in May.

Winik highlights three events that all occurred within a fortnight. First there was the evacuation and fall of the Confederate capital of Richmond between 2-4 April.

Second, with the writing on the wall, Lee surrendered to Grant on 9 April in the McLean house at Appomattox Courthouse.

Lee signs the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia, witnessed by Ulysses S Grant and his officers.

The surrender terms were quite favourable to the Confederates, but there was a lingering fear that undefeated troops would take to the mountains and wage guerrilla war for decades. However, Confederate General Joseph E Johnston surrendered his large army to William Tecumseh Sherman at Bennett Place in North Carolina on 26 April. Fighting overall in the Civil War came to an end by the end of May 1865.

And third, was the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln on 14 April (he actually died the following day). This had major ramifications for the post-bellum rapprochement that Linclon had long envisaged, and with the ascendancy of his Vice President Andrew Johnson to the highest office, there was no certainty that a lasting peace would prevail.

Not all reviewers agree with Winik’s interpretation that April 1865 was so crucial. Events earlier in the same year, and perhaps since the Confederate defeat at Gettysburg in 1863 meant that the Confederacy was always destined to fail.

But April 1865 is an easy read. One aspect that I really appreciated were the vignettes of the main protagonists that Winik interspersed with the main chronology of events. It’s remarkable that the Confederates were as successful on the battlefield over the course of the war, albeit their cause ultimately ending in failure, given the jealousies between many of their general officers. I guess most soldiers who reach general rank must have pretty big egos.

Over the course of our road trips across the USA, Steph and I have taken the opportunity of visiting several historical sites connecting with the Civil War.

In 2017, we drove from Georgia to Minnesota, taking in Savannah (the destination of Sherman’s March to the Sea in November and December 1864, and through the Appalachians, and crossing (as we did in 2019) much of the region in Virginia and West Virginia in particular where many of the battles were fought.

In 2019, on a trip that took in many northeast and Atlantic states, we visited both the Gettysburg battlefield site and Appomattox Court House.

In 2018, travelling from Maine to Minnesota, we passed through Ohio, the birthplace of two of the most famous generals of the Civil War: Grant (in Point Pleasant) and Sherman (in Lancaster); and the boyhood home—in Somerset—of Philip Sheridan (who was born in Albany, NY, but grew up in Ohio).

The mural of Sherman on the wall of the Glass Museum in Lancaster that I illustrated in that post is no longer there. It has been whitewashed over!

I’ve just completed an abridged biography (see below, down from four volumes) of General Lee. Rather tough going, I must say, with so much miniscule detail rather than a broader horizon to explore.

¹Over 620,000 killed. In fact, more soldiers died from post combat infection of wounds or from diseases like dysentery and measles that spread like wildfire through camps. See this link for a breakdown of the statistics.

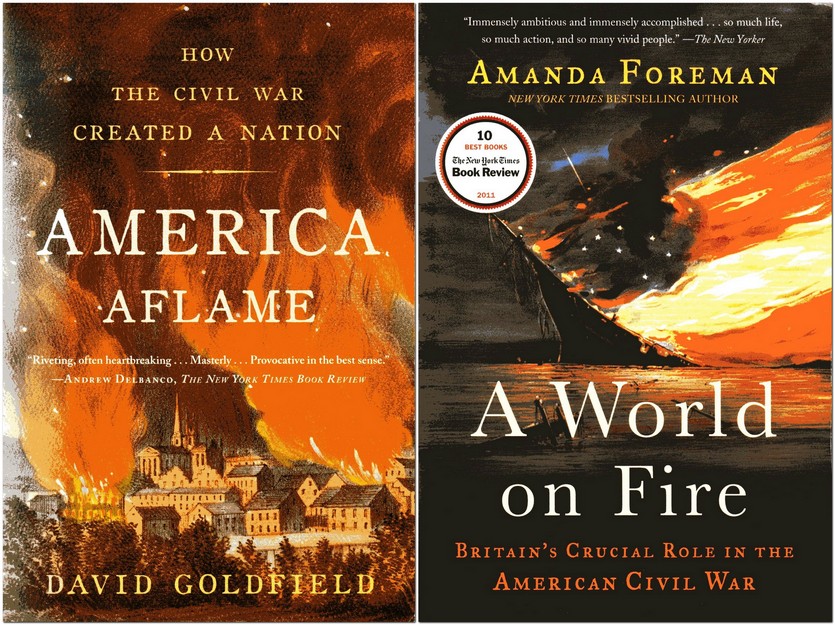

² Here are the books about the Civil War that I have read: