I’ve just finished reading Roger Osbourne’s very interesting and well written account of the Industrial Revolution in Britain during the 18th century.

I’ve just finished reading Roger Osbourne’s very interesting and well written account of the Industrial Revolution in Britain during the 18th century.

I am particularly interested in the 18th century, turn of the 19th. It was a period of great invention and innovation, set against a backcloth of social change and upheaval, of international conflict, and revolution. It was also a time of increasing economic prosperity in Britain. But ‘revolution’ it was not, at least not in the sense that we most often understand the term, since the start and the development of what we now call the ‘Industrial Revolution’ took place over at least 150 years.

One of the reasons for my interest is that I grew up in the southeast Cheshire – North Staffordshire area, where many of the early developments of the Industrial Revolution were adopted, particularly in coal mining and iron production, as well as textiles. In fact some of the most important areas for industrial innovation, such as Coalbrookdale in Shropshire where Abraham Darby first used coal instead of charcoal in a blast furnace to produce cast iron as early as 1709, or at Cromford, in the Derwent valley north of Derby, where Richard Arkwright established his cotton mill in 1771, were only about 40 miles away to the west and the east of where I grew up.

One of the main points that Osbourne makes up front is the key role that coal made during the Industrial Revolution, initially for heating, and then for mechanical energy from coal-fired steam engines. As early as 1712, a Newcomen atmospheric engine was built to pump water from a mine in Dudley, northwest of Birmingham. Later on in the century, James Watt’s further developments (sponsored by Birmingham entrepreneur Matthew Boulton) of the high pressure steam engine opened up the possibility of not only greater efficiency of the engines themselves, and more economical use of coal, but also the use of steam engines to power machinery. This was widely adopted for the burgeoning textile industries of Lancashire and Yorkshire. But it was Cornishman Richard Trevithick who demonstrated the first use of locomotive power in 1801 and the first steam locomotive on rails in 1804.

In the video below, the Boulton and Watt beam engines powered by steam, built in 1812, are still operational today. A pumping station was built alongside the Kennet & Avon Canal in Wiltshire to lift water to the lock system on the canal. Replaced by electric power today, the old steam engines are fired up from time-to-time, and we visited in 2008 on one of those occasions.

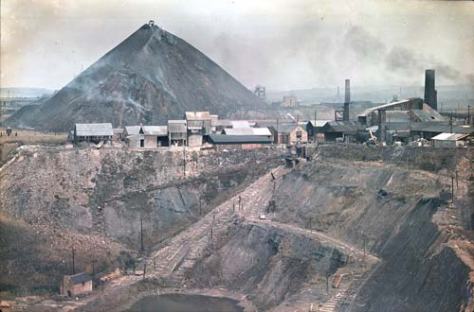

Landowners who had coal under their land made fortunes, particularly in the north-east of England, along the Tyne valley. Vast quantities of coal were shipped out to the metropolis of London, which by 1750 had a population of half a million. We recently visited the ‘stately home’ of one of the coal barons at Seaton Delaval just north of Newcastle upon Tyne. All over the coalfields of the country, the extraction of coal, mostly in deep mines, left a blight on the landscape in the form of tall, conical slag heaps. All over The Potteries – the six towns of Tunstall, Burslem, Hanley, Stoke, Longton and Fenton that comprise Stoke-on-Trent in North Staffordshire – these slag heaps and marl pits (from which clay was extracted for the ceramics industry) dotted and blighted the landscape. And as coal was used to heat houses and fire the bottle ovens in the ceramics industry there was a continuous pall of smoke over the city.

Coal mine and slag heap, probably near Longton.

Copyright: Staffordshire Museum Service.

When we I visited Little Moreton Hall, just south of Congleton in Cheshire, a week ago, our route crossed The Potteries from south to north, I was struck how much the landscape of the area had changed over the past half century. When the coal industry collapsed in recent decades – after Margaret Thatcher saw off the National Union of Mineworkers in the 1980s – and the demand for coal had in fact been declining, many communities were left with blighted landscapes of industrial decline, with these eyesore slag heaps dominating the skyline. In the 1960s I traveled every day from my home in Leek to high school on the south side of the Potteries. And the route we took went past some of the tallest slag heaps near Norton and Cobridge. One of these was actually on fire – the result of spontaneous combustion within the tip, and for years efforts were made to bring it under control.

Today, many of the tips have disappeared and it would be difficult to even spot a disused mine head. That’s because a huge effort, and no doubt huge sums of money, have been spent to rehabilitate these derelict sites. In some places you’d hardly realize that mining had actually gone on there. In the centre of Hanley for instance, Forest Park has been developed at one particular site, and the ‘Cobridge Alps’ have been graded to form a more rolling landscape. Some sites have even become nature reserves. The next two photos illustrate the before and after scenarios, taken at Glebe Colliery in Fenton (courtesy of Steven Birks and the North Staffordshire Potteries web site).

As a botany and geography student in the 1960s I was quite interested in the whole topic of derelict land reclamation. Reclaiming these derelict sites is not straightforward. First they have be graded and slopes stabilized, then plants have to be identified that will actually grow and thrive. I’ve already alluded to the problems of combustion of the coal heaps. But a coal heap is not a particularly hospitable substrate for plants to grow. Even more so if the ‘soil’ is polluted by heavy metals such as copper and zinc that are found in the tips in mining areas, such as Cornwall and the Swansea Valley, where these minerals were extracted or smelting was the predominant industry during the Industrial Revolution. During the first field trip I made as a geography student at Southampton University we visited to derelict land rehabilitation projects in the Swansea Valley. Once I’d moved to Birmingham University in 1970 I took a couple of courses on the relationship of genetics and ecology – genecology, and some of the best examples have to do with the frequency of heavy metal tolerant grasses that have evolved to survive on polluted soils at may of these industrial sites. Seeds can be collected to sow reclaimed sites.

As a botany and geography student in the 1960s I was quite interested in the whole topic of derelict land reclamation. Reclaiming these derelict sites is not straightforward. First they have be graded and slopes stabilized, then plants have to be identified that will actually grow and thrive. I’ve already alluded to the problems of combustion of the coal heaps. But a coal heap is not a particularly hospitable substrate for plants to grow. Even more so if the ‘soil’ is polluted by heavy metals such as copper and zinc that are found in the tips in mining areas, such as Cornwall and the Swansea Valley, where these minerals were extracted or smelting was the predominant industry during the Industrial Revolution. During the first field trip I made as a geography student at Southampton University we visited to derelict land rehabilitation projects in the Swansea Valley. Once I’d moved to Birmingham University in 1970 I took a couple of courses on the relationship of genetics and ecology – genecology, and some of the best examples have to do with the frequency of heavy metal tolerant grasses that have evolved to survive on polluted soils at may of these industrial sites. Seeds can be collected to sow reclaimed sites.

In 1966 I made my first visit to Coalbrookdale. As a high school student in the Lower Sixth (age 17) I attended a weekend residential course at Attingham Park (now a National Trust property) just south of Shrewsbury in Shropshire. The topic was all about industrial derelict land reclamation, and we were treated to a keynote lecture by the eminent Professor of Geography and land use expert, Sir Dudley Stamp (he died about three months later). And I also remember two botanists from Newcastle University, Oliver Gilbert and AW Davison, a lichenologist and bryologist, respectively who lectured about the use of lichens and mosses as indicators of polluted soil. And then we had the tour of Coalbrookdale and Ironbridge – before it became a UNESCO World Heritage Site and on the tourist trail.

In 1966 I made my first visit to Coalbrookdale. As a high school student in the Lower Sixth (age 17) I attended a weekend residential course at Attingham Park (now a National Trust property) just south of Shrewsbury in Shropshire. The topic was all about industrial derelict land reclamation, and we were treated to a keynote lecture by the eminent Professor of Geography and land use expert, Sir Dudley Stamp (he died about three months later). And I also remember two botanists from Newcastle University, Oliver Gilbert and AW Davison, a lichenologist and bryologist, respectively who lectured about the use of lichens and mosses as indicators of polluted soil. And then we had the tour of Coalbrookdale and Ironbridge – before it became a UNESCO World Heritage Site and on the tourist trail.

In the course of just three decades the evidence of the coal mining industry that powered the Industrial Revolution in the 1700s and into the 20th century has all but disappeared from our landscape. Even tracking down photographs of the coal mines and slag heaps has been quite difficult; history has slipped away before our eyes. Nevertheless, our environment is much better now that we do not have to suffer constant exposure to coal smoke. However, what we enjoy today is undoubtedly built upon the innovation and invention that flourished when coal was king.

Two other interesting facts emerged from Roger Osbourne’s book that perhaps I’ll have to look into further. First, how the 18th century inventors relied upon and enforced the patent system to protect their inventions. And second, how many of the industrialists of the time were Nonconformists – Methodists, Baptists, Quakers, and the like. And I haven’t yet touched on the legacy of the potter Josiah Wedgwood and the canal builders of the 18th century such as James Brindley who lived much of his life in my hometown of Leek.