Earlier this week, I enjoyed—on catch-up TV—the third episode (about South America) of David Attenborough’s latest series on the BBC, Seven Worlds, One Planet. Here’s a taster of this wonderful series.

Once again, Sir David has treated us to a feast of images from the natural world, accompanied by his typical understated but informative commentary. And, as I was saying to Steph afterwards, cinematic technology such as drones with HD cameras has added a new dimension to natural history storytelling.

Most natural history programs routinely highlight loss of biodiversity (and its causes such as climate change), and Seven Worlds, One Planet is no exception. We live on a species-rich planet. But with so many programs about the natural world appearing on our screens, do we take for granted the diversity of nature and its millions of animal, plant, fungal, and microbial species?

Apart from Seven Worlds, One Plant, a couple of other biodiversity-related items on the radio have caught my attention in recent weeks.

The first, at the beginning of November, was an item on the early morning Today news and current affairs program on BBC Radio 4 (that I listen to in bed as I enjoy my early morning cup of tea) about an initiative to unravel the genetic code of all known 60,000 species of eukaryotes [1] in the United Kingdom.

Known as the Darwin Tree of Life Project (a most appropriate name!) it’s the UK arm of a worldwide initiative, the Earth BioGenome Project (EBP) to sequence the genomes of all 1.5 million known species of animals, plants, protozoa and fungi on Earth. That’s some challenge!

Each day, Charles Darwin would take a stroll along the Sandwalk at the bottom of his garden, where ideas about species and evolution not doubt swirled around his mind.

Why is the Darwin Tree of Life Project only possible now?

As stated on the EBP website: Powerful advances in genome sequencing technology, informatics, automation, and artificial intelligence, have propelled humankind to the threshold of a new beginning in understanding, utilizing, and conserving biodiversity. For the first time in history, it is possible to efficiently sequence the genomes of all known species, and to use genomics to help discover the remaining 80 to 90 percent of species that are currently hidden from science.

But also cost. Since the very first genome was sequenced in 1995 (of a pathogenic Gram-negative bacterium) the costs of sequencing have plummeted making it now economically feasible to even contemplate a project on the scale of the Darwin Tree of Life Project.

The UK component (launched on 1 November) is led by the Wellcome Sanger Institute in Cambridge in collaboration with Natural History Museum in London, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Earlham Institute, Edinburgh Genomics, University of Edinburgh, EMBL-EBI (the European Bioinformatics Institute), and others. It is estimated that the project will take ten years to complete, costing £100 million over the first five years.

Dr Ken McNally

Molecular genetics and genomics have come a long, long way in just a few years. Just read the excellent 2014 analysis [2] by my former IRRI colleague, molecular geneticist Ken McNally how the latest developments in genomics (and related techniques) could contribute towards the conservation and use of biological diversity. And I’m sure things have progressed since Ken gazed into his ‘omics’ crystal ball just five years ago.

It’s remarkable how the science has accelerated in just a few decades. I completed my PhD under the supervision of Jack Hawkes, one of the world’s leading potato taxonomists and genetic resources conservation pioneer. In the 1960s (with colleagues from the immunology department at the University of Birmingham) he demonstrated that serology [3] could help clarify relationships between wild potato species (genus Solanum) [4].

As a graduate student at Birmingham in the early 1970s, I used a technique known as gel electrophoresis to separate potato tuber proteins, using the resultant patterns (position, and presence or absence) to better understand the relationships of different classes of cultivated potato.

As a graduate student at Birmingham in the early 1970s, I used a technique known as gel electrophoresis to separate potato tuber proteins, using the resultant patterns (position, and presence or absence) to better understand the relationships of different classes of cultivated potato.

Since the 1980s several different classes of molecular markers have been developed, and today—through whole genome sequencing—we can begin to decipher the complex relationship between genetic code and phenotypic and physiological diversity. We are beginning to explain better why species are different and how they are adapted to their environments.

My own research at IRRI and in collaboration with former colleagues Brian Ford-Lloyd, John Newbury, and Parminder Virk at the University of Birmingham in the mid-1990s, used molecular markers to analyse the diversity of rice varieties [5].

Another of the Birmingham-IRRI papers [6] was among the first (if not the first) to show a clear (and predictive) relationship between molecular markers (in this case RAPD markers) and appearance and performance of rice plants in the field.

Much of this rice research was aimed at understanding the diversity within a single species, Oryza sativa, which is grown over millions upon millions of hectares across the world. With hindsight, that research looks quite primitive, even though it was cutting edge at the time. Since the rice genome was first sequenced at the turn of the millennium, things have moved on apace, and more than 3000 genomes have been analysed to understand rice diversity.

Much of this rice research was aimed at understanding the diversity within a single species, Oryza sativa, which is grown over millions upon millions of hectares across the world. With hindsight, that research looks quite primitive, even though it was cutting edge at the time. Since the rice genome was first sequenced at the turn of the millennium, things have moved on apace, and more than 3000 genomes have been analysed to understand rice diversity.

But the Darwin Tree of Life Project will look across species, and hopefully keep a careful track of exactly which specimens/individuals are sequenced.

So, this brings me to the other radio broadcast I mentioned earlier. It was a discussion—about hybridisation between species—in the regular Thursday night In Our Time program, hosted by that doyen of broadcasting, Lord Melvyn Bragg with three biologists: Professor Steve Jones, Emeritus Professor of Human Genetics at University College London; Dr Sandra Knapp, from the Natural History Museum and a specialist in the taxonomy of the nightshade family, Solanaceae (that includes potatoes, tomatoes, eggplants, and many more); and zoologist Dr Nicola Nadeau of The University of Sheffield University. You can listen to that discussion here.

So, this brings me to the other radio broadcast I mentioned earlier. It was a discussion—about hybridisation between species—in the regular Thursday night In Our Time program, hosted by that doyen of broadcasting, Lord Melvyn Bragg with three biologists: Professor Steve Jones, Emeritus Professor of Human Genetics at University College London; Dr Sandra Knapp, from the Natural History Museum and a specialist in the taxonomy of the nightshade family, Solanaceae (that includes potatoes, tomatoes, eggplants, and many more); and zoologist Dr Nicola Nadeau of The University of Sheffield University. You can listen to that discussion here.

I found this discussion particularly interesting because in much of my research on potatoes, various legume species, and rice over many years I studied the relationships between species, and their ability to hybridise.

From the outset, Melvyn Bragg was working from the premise that species are distinct and rarely hybridise. That’s a reasonable point of view to take. After all, we can describe and identify millions of species based on the commonality of appearance (morphology) that individuals of one species share and make them different from other species. Like breeds with like.

Hybrids are less common between different animal species. Breeding behavior is a powerful isolating mechanism between species.

In plants, hybridisation is more common. However, there are many pre- and post-fertilization mechanisms that reduce the potential for hybridisation. It doesn’t matter if one can bring different species into cultivation alongside and successfully produce hybrids. In nature, many species never come into contact with each other because they grow in different habitats (in the same or different geographical regions). If they do grow in close (or relatively close) association, different species may not be reproductively compatible. Pollen from one species may fail to germinate on another or, if germinating, fail to achieve fertilization. Hybrid embryos may fail to develop, or even if hybrid seeds are formed, the plants are weak and fail to survive.

In the fluorescence images below (from pollinations between different tomato species that I used in class experiments with some of my students when I was teaching at Birmingham in the 1980s), a compatible pollination is shown in the images on the left and bottom. The other two images show poor pollen germination and growth in incompatible pollinations. Yet one or two pollen tubes have grown ‘normally’.

So, hybrids do occur, and are often successful in disturbed habitats that do not favor one parent or the other. There is a potential for species to expand their gene pools by exchange of some genetic material—or introgression, as it is called—that I described in one of my first blog posts in 2012.

Thank goodness plants can and do hybridise. As Steve Jones pointed out during the discussion, much of agriculture depends on ancient hybridisations and our ability to exploit cross compatibility between species. Wheat, one of the most important staple crops worldwide, is an ancient hybrid between three grass species. Potatoes evolved following crosses between different species (sometimes with different chromosome numbers) and hybrids were maintained by farmers since potatoes are grown vegetatively from tubers, not from seeds. Once a hybrid is formed then it can be maintained indefinitely through tubers.

Through hybridisation between cultivated varieties and wild species important characteristics or traits such as disease resistance can be added to the crops that farmers grow.

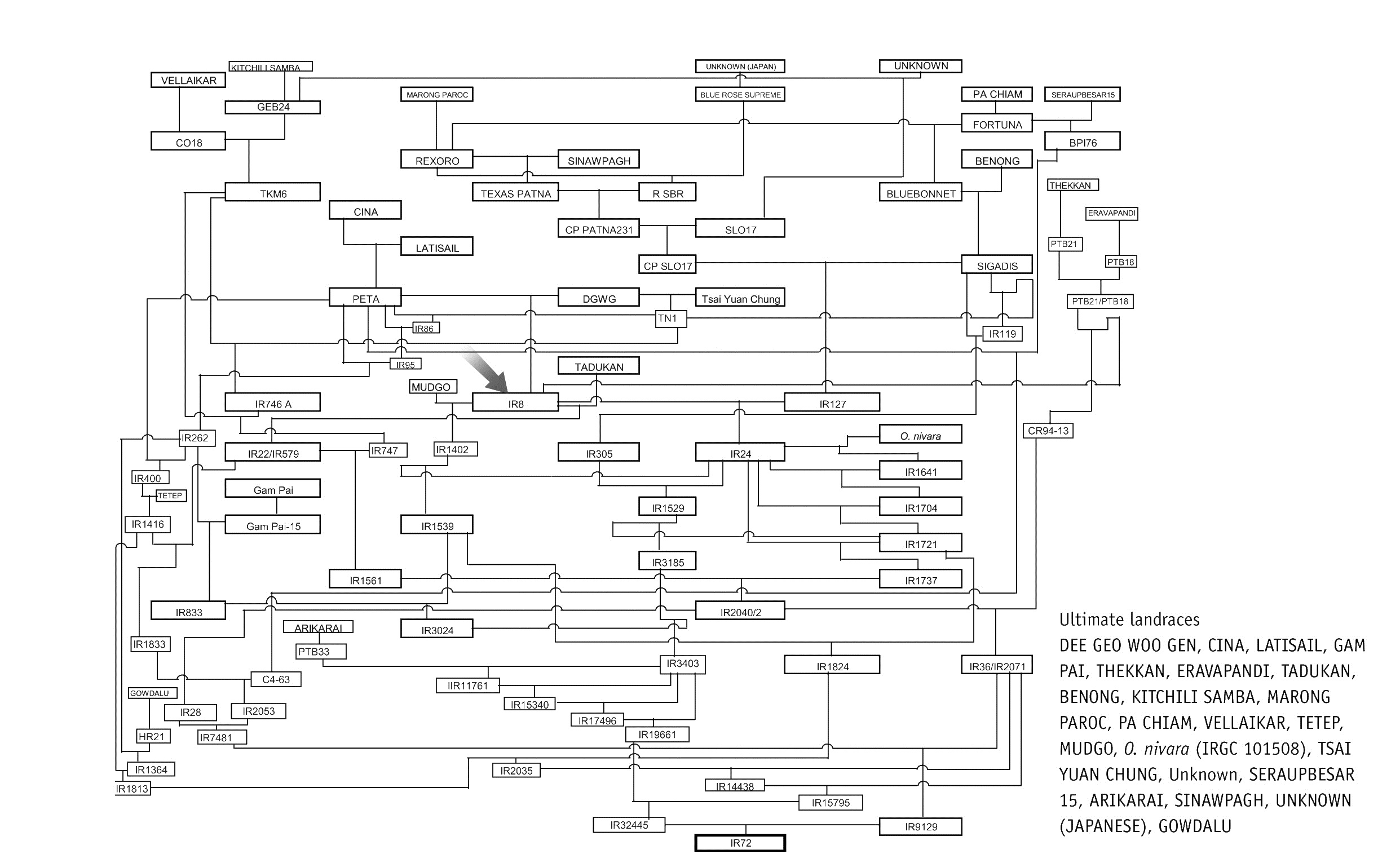

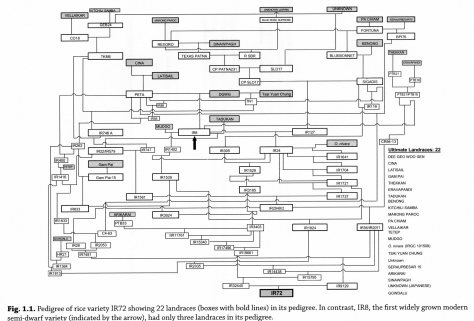

Just take this example from rice, showing the pedigree of the variety IR72 that was released in 1990. Many landrace varieties were crossed to produce this variety. But also very importantly, a wild rice, O. nivara (a close relative of O. sativa with which it crosses easily, and in the same genepool – see diagram below) was the source of resistance to grassy stunt virus, and it was this resistance that made IR72 such a successful variety.

One of the most important biodiversity initiatives in recent years has been the Crop Wild Relatives Project, started in 2011, managed by the Crop Trust with the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and many partners around the world. It is funded by the Government of Norway.

The project has a number of priorities including collection of crop wild relatives and their conservation around the world. But also evaluation and pre-breeding, exactly the same type of approach I used in my own studies on species relationships. This research aims to determine the gene pools (GP on the diagram below) of crops and their wild relatives (a concept developed by Jack Harlan and JMJ de Wet in 1971 [7]), and provides plant breeders with useful and important information about the value of different wild species, and what traits can be exploited for greater adaptation.

The project has a number of priorities including collection of crop wild relatives and their conservation around the world. But also evaluation and pre-breeding, exactly the same type of approach I used in my own studies on species relationships. This research aims to determine the gene pools (GP on the diagram below) of crops and their wild relatives (a concept developed by Jack Harlan and JMJ de Wet in 1971 [7]), and provides plant breeders with useful and important information about the value of different wild species, and what traits can be exploited for greater adaptation.

These are exciting times for the collection, conservation, evaluation, and use of the many species of crop wild relatives. With regular access to this valuable germplasm in genebanks around the world, and data on how they can be hybridised, and with the additional information about plant genomes, then plant breeders can begin to use these species more strategically, even using GM approaches. However, the cultivation of GM crops is banned in many countries including the countries of the European Union (one of the biggest mistakes the European Union has collectively made), even though these GM technologies can significantly reduce the time and effort required to transfer useful traits from one species into another.

Scientists have many tools in the plant breeding toolbox. It all starts with a seed, collected from nature, studied in the laboratory, and conserved in genebanks. There’s hope yet.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

[1] Eukaryotic species are defined as organisms whose cells have a nucleus enclosed within membranes, unlike prokaryotes, which are unicellular organisms that lack a membrane-bound nucleus, mitochondria or any other membrane-bound organelle (Bacteria and Archaea).

[2] McNally, KL. 2014. Exploring ‘omics’ of genetic resources to mitigate the effects of climate change. In: M Jackson, B Ford-Lloyd and M Parry (eds.) Plant Genetic Resources and Climate Change. CABI climate change series 4, CABI Wallingford.

[3] See Hawkes, JG (ed.) 1968. Chemotaxonomy and Serotaxonomy. Systematics Association and Academic Press, London. pp. 299.

[4] Hawkes published several immunological studies in the mid- to late 60s on North American and Mexican species of potato, with Richard Lester, one of his PhD students (and later Lecturer in the Department of Plant Biology at Birmingham).

[5] Virk, P.S., B.V. Ford-Lloyd, M.T. Jackson & H.J. Newbury, 1995. Use of RAPD for the study of diversity within plant germplasm collections. Heredity 74, 170-179. PDF

[6] Virk, P.S., B.V. Ford-Lloyd, M.T. Jackson, H.S. Pooni, T.P. Clemeno & H.J. Newbury, 1996. Predicting quantitative variation within rice using molecular markers. Heredity 76, 296-304. PDF

[7] Harlan, JR and JMJ de Wet, 1971. Toward a rational classification of cultivated plants. Taxon 20, 509-517.

The most celebrated of the family was Alexander (born in 1830) who traveled extensively and built

The most celebrated of the family was Alexander (born in 1830) who traveled extensively and built

After I’d posted this story, David Thompson left the comment below, to which I have just replied. And he rightly raises the spectre of

After I’d posted this story, David Thompson left the comment below, to which I have just replied. And he rightly raises the spectre of

Well, more of a nightmare, actually.

Well, more of a nightmare, actually.

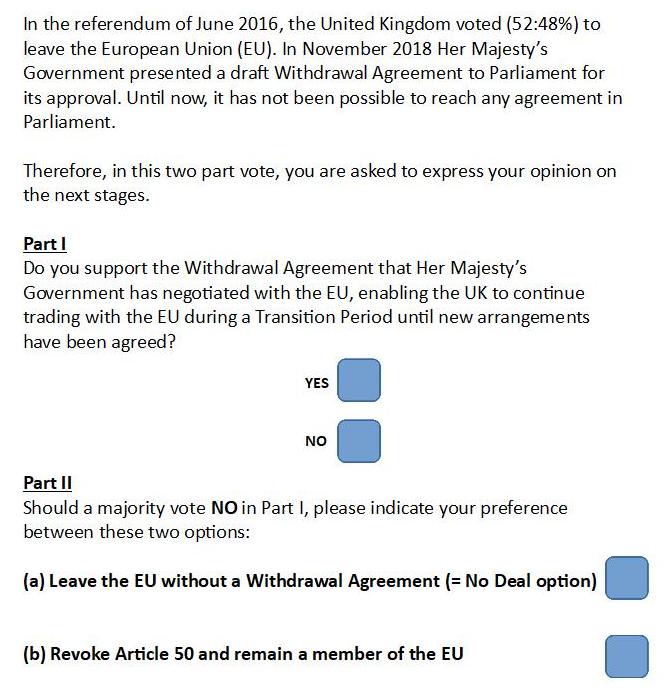

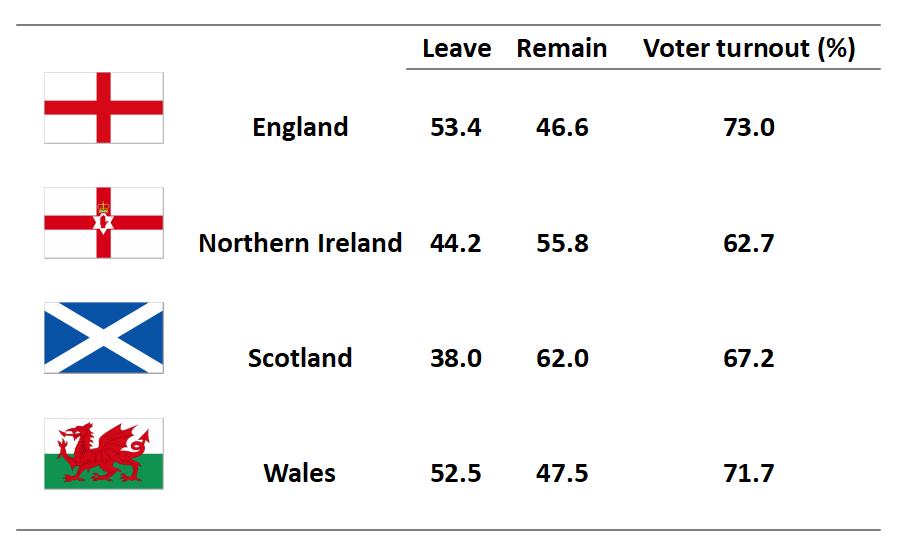

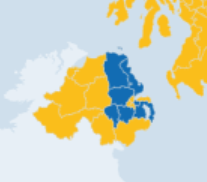

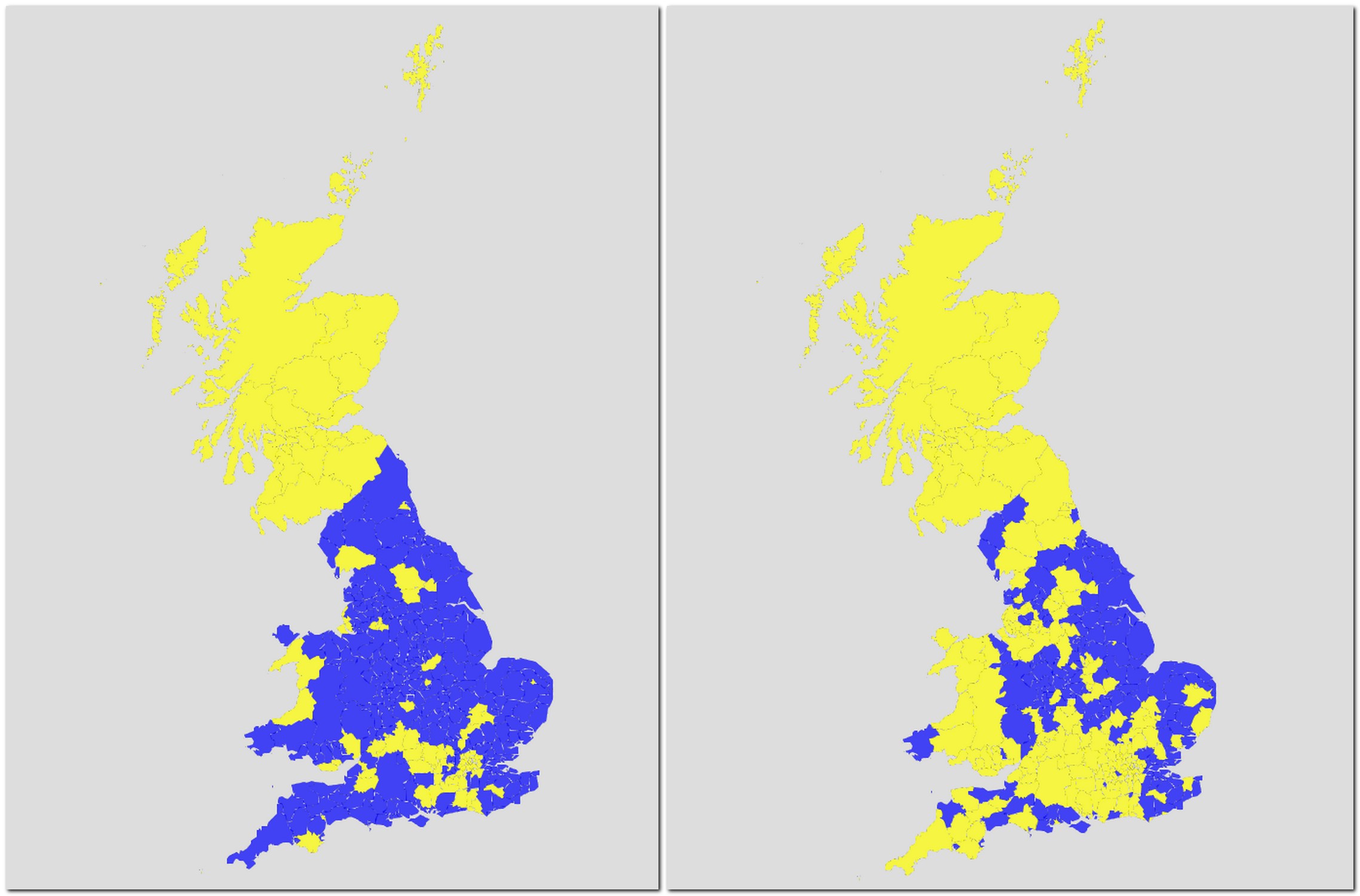

Tick tock. Tick tock. We are inching inexorably towards the UK’s departure from the European Union (EU).

Tick tock. Tick tock. We are inching inexorably towards the UK’s departure from the European Union (EU). Many seem almost insoluble, given the almost even split in opinion (in 2016) among the nation’s voters, and the parliamentary deadlock that currently blights the House of Commons. Party before nation!

Many seem almost insoluble, given the almost even split in opinion (in 2016) among the nation’s voters, and the parliamentary deadlock that currently blights the House of Commons. Party before nation!

With just 32 days before the UK is due to leave the European Union (EU), potentially crashing out without a deal if the Withdrawal Agreement negotiated over many months with the EU is once again rejected by Parliament, Theresa May has again kicked the ‘Brexit can’ down the road. Parliament will not hold a ‘

With just 32 days before the UK is due to leave the European Union (EU), potentially crashing out without a deal if the Withdrawal Agreement negotiated over many months with the EU is once again rejected by Parliament, Theresa May has again kicked the ‘Brexit can’ down the road. Parliament will not hold a ‘

Brexiteers (predominantly Tory English MPs) continue to see a role and influence of the UK projecting ‘neo-colonialist’ power (‘lethality’ even) far beyond what this small island nation with a shrinking economy can hope, or should ever again aspire, to achieve. Just take the

Brexiteers (predominantly Tory English MPs) continue to see a role and influence of the UK projecting ‘neo-colonialist’ power (‘lethality’ even) far beyond what this small island nation with a shrinking economy can hope, or should ever again aspire, to achieve. Just take the

But it’s Remain supporters who are getting plucked and stuffed.

But it’s Remain supporters who are getting plucked and stuffed. Short-sighted, except one, perhaps.

Short-sighted, except one, perhaps.

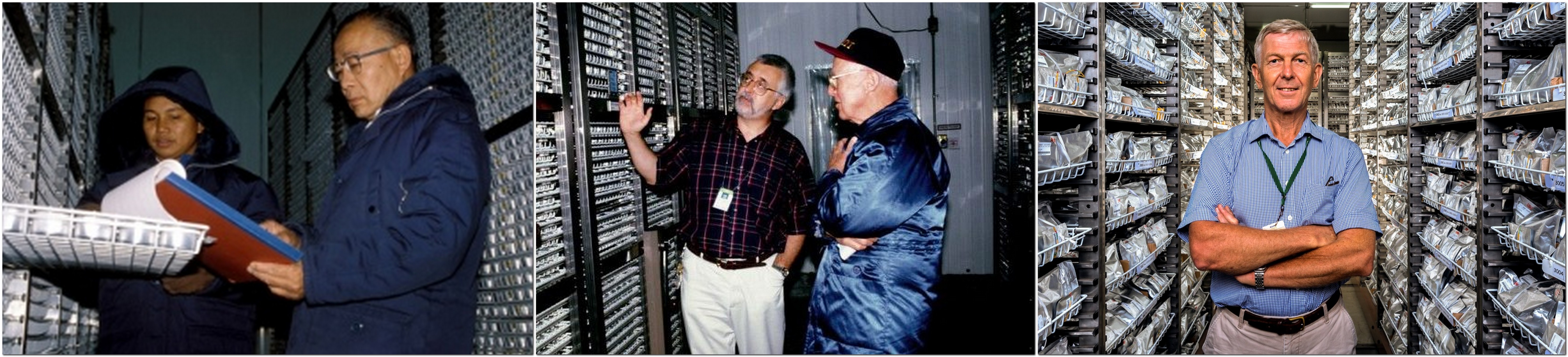

materials, among others. You can check the status of the IRRI collection (and many more genebanks in the

materials, among others. You can check the status of the IRRI collection (and many more genebanks in the

I have the Brexit blues.

I have the Brexit blues.

But in many of the poorest countries of the world, development aid from the UK and other countries has brought about real change, particularly in the agricultural development arena, one with which I’m familiar, through the work carried out in

But in many of the poorest countries of the world, development aid from the UK and other countries has brought about real change, particularly in the agricultural development arena, one with which I’m familiar, through the work carried out in

Our accession to the EEC came a decade after the President of France, Charles de Gaulle famously failed to back the UK’s application to become a member stating that the British government lacks commitment to European integration. In November 1967, he vetoed the UK’s application a second time.

Our accession to the EEC came a decade after the President of France, Charles de Gaulle famously failed to back the UK’s application to become a member stating that the British government lacks commitment to European integration. In November 1967, he vetoed the UK’s application a second time. One of the most important strategic decisions we took was to locate one staff member, Dr Seepana Appa Rao, in

One of the most important strategic decisions we took was to locate one staff member, Dr Seepana Appa Rao, in  The leader of the Lao-IRRI Project was Australian agronomist, Dr John Schiller, who had spent about 30 years working in Thailand, Cambodia and Laos, and whose untimely death was announced just yesterday¹.

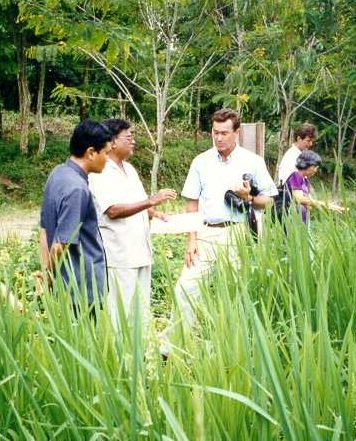

The leader of the Lao-IRRI Project was Australian agronomist, Dr John Schiller, who had spent about 30 years working in Thailand, Cambodia and Laos, and whose untimely death was announced just yesterday¹. Until Appa Rao moved to Laos, very little germplasm exploration had taken place anywhere in the country. It was a total germplasm unknown, but with excellent collaboration with national counterparts, particularly Dr Chay Bounphanousay (now a senior figure in Lao agriculture), the whole of the country was explored and more than 13,000 samples of cultivated rice collected from the different farming systems, such as upland rice and rainfed lowland rice. A local genebank was constructed by the project, and duplicate samples were sent to IRRI for long-term storage as part of the International Rice Genebank Collection in GRC. Duplicate samples of these rice varieties were also sent to the

Until Appa Rao moved to Laos, very little germplasm exploration had taken place anywhere in the country. It was a total germplasm unknown, but with excellent collaboration with national counterparts, particularly Dr Chay Bounphanousay (now a senior figure in Lao agriculture), the whole of the country was explored and more than 13,000 samples of cultivated rice collected from the different farming systems, such as upland rice and rainfed lowland rice. A local genebank was constructed by the project, and duplicate samples were sent to IRRI for long-term storage as part of the International Rice Genebank Collection in GRC. Duplicate samples of these rice varieties were also sent to the

I first met John in November 1991, a few months after I’d joined IRRI. He and I were part of a group of IRRI scientists attending a management training course, held at a beach resort bear Nasugbu on the west coast of Luzon, south of Manila. The accommodation was in two bedroom apartments, and John and I shared one of those, so I got to know him quite well.

I first met John in November 1991, a few months after I’d joined IRRI. He and I were part of a group of IRRI scientists attending a management training course, held at a beach resort bear Nasugbu on the west coast of Luzon, south of Manila. The accommodation was in two bedroom apartments, and John and I shared one of those, so I got to know him quite well.

That’s what the

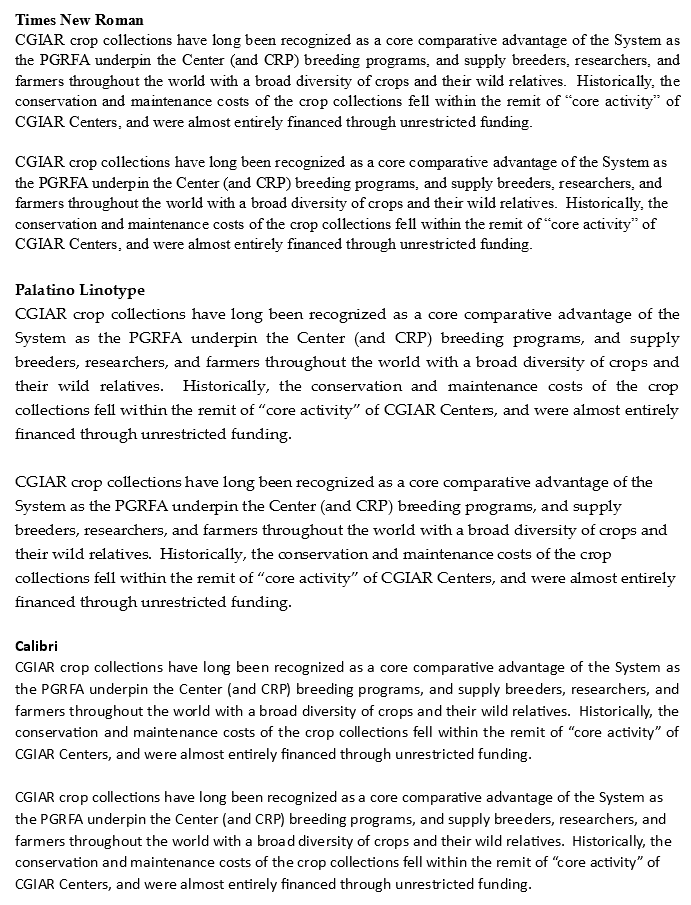

That’s what the Sans Serif typefaces have become more popular in recent years, no doubt because of the Microsoft default font decision, although until the release of Calibri,

Sans Serif typefaces have become more popular in recent years, no doubt because of the Microsoft default font decision, although until the release of Calibri,