That’s a quotation from a poem by Poet Laureate John Dryden, and distant cousin to the family whose home we visited last week. Summer had arrived, and – having prepared a picnic – we headed 50 miles southeast to Canons Ashby in Northamptonshire.

Canons Ashby House and estate was acquired by the National Trust only about 30 years ago. It had been offered to the Trust several decades earlier, but the Dryden family (which continues to have connections with Canons Ashby) was unable to provide the financial support needed to enable the Trust to take on the necessary long-term commitment. That changed around 1980 when the National Trust was able to secure public funds to acquire and restore the house that had already declined into a near terminal state of disrepair.

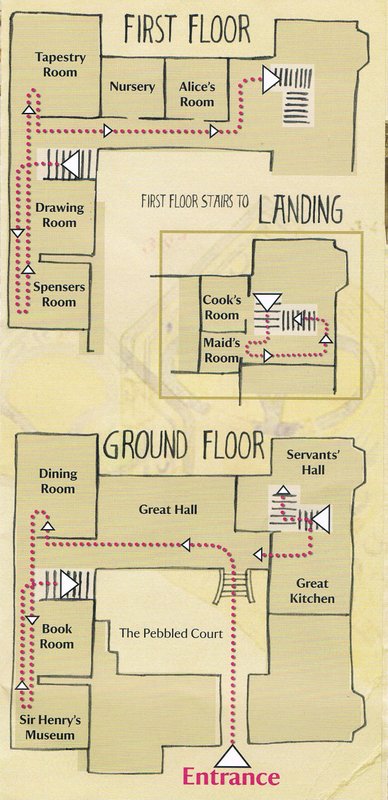

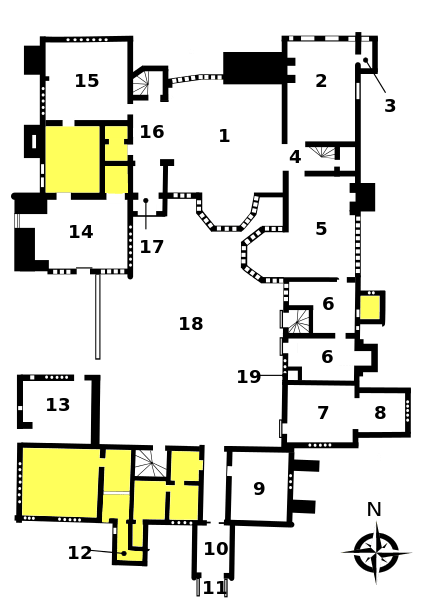

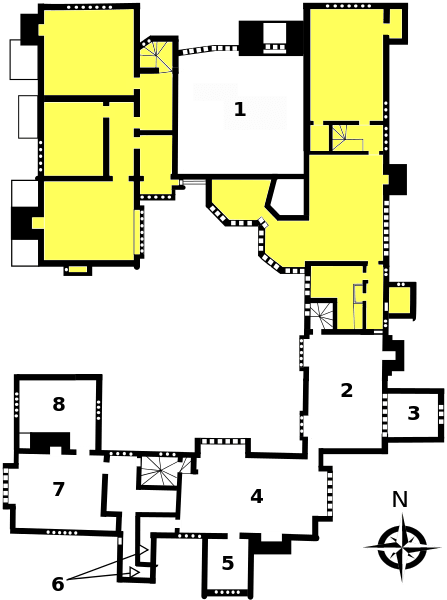

1. Car park; 2. Reception; 3. Toilets; 4. House entrance; 5. Garden entrance; 6. Steps into park; 7. Parkland; 8. Priory Church of St Mary; 9. The Norwell; 10. The Orchard; 11. Site of Medieval Village; 12. The Paddock.

Three decades on and you wouldn’t believe what a transformation has taken place, and Canons Ashby is indeed one of the nicer National Trust properties that we have visited since becoming members at the beginning of 2011.

The 2500 acre estate and house was inherited by Sir Henry Dryden in 1837 (the 8th generation of his family to live at Canons Ashby), when he was just 19. Leaving his studies at Cambridge, he set about rescuing the house from more than 100 years of neglect, and made some extensive alterations to the rooms inside.

But the origins of the estate go much further back. An Augustinian priory was founded there in the 13th century, and the Priory Church of St Mary is all that remains today of a much larger settlement. And from Tudor times, and after the Dissolution of the monasteries, stones from the priory were used in the construction of the original parts of the house. The Priory Church is one of just a handful of privately-owned churches in England. The site of a medieval village lies to the north side of the house (11 on the site plan). Apparently, the Black Death badly affected Canons Ashby in the mid-14th century and more than half of the village died.

The house itself is surrounded by a small formal garden leading southwards towards the Lion Gate through what is now a vegetable garden. Beautifully manicured lawns and flower beds grace the south side of the house, but to the west is a walled garden, the Green Court, planted with yews, which provided the family some degree of privacy from outsiders and servants alike.

An archway (in part of the original Tudor building) leads into the Pebbled Court, and steps leading into the Great Hall. On the ground floor there are several rooms open to visitors: the hall itself, with an impressive display of swords and muskets on the walls and over the fireplace; the paneled dining rooms (with some impressive portraits including Sir John Dryden who erected paneling in many of the rooms in the 18th century); the book room/study, and a small room that was a museum developed by Sir Henry. Above the fireplace in the dining room is a mirror, slightly tilted forwards to enable anyone with their back to the window (but facing the fireplace) to see the garden (Green Court) outside.

On the first floor, two rooms in particular are impressive: the Drawing Room with its fireplace and domed, plastered ceiling; and the Tapestry Room, a bedroom with beautiful tapestries hanging on the walls. In another bedroom, Spensers Room, some of the oak paneling has been removed to reveal the remains of some fine Tudor wall paintings.

Off a long gallery on the north side of the building there is a nursery, and the bedroom of Alice, Sir Henry’s only daughter – who became a well-known photographer who established a dark room in the cellars. Descending gingerly through low-framed doors and winding stairs in the oldest part of the house, there is the Servants’ Hall (once thought to be the original family dining room) and the kitchen (with its incredibly high, vaulted ceiling). The Servants’ Hall is rather intriguing, for a couple of reasons at least. The walls are covered in paneling, brilliantly decorated with coats of arms and escutcheons, some of which seem to indicate a link with Freemasonry (even though the Freemasons as such were not founded for a couple of centuries later). At least one window was bricked up – which previously had a view over the Green Court – so that servants could not watch the family at play.

From Tudor times onwards, the Dryden family were harshly Puritan, and supported Parliament during the Civil Wars of the 1640s. In the Green Court there is a statue of a shepherd boy reputed to have warned the Parliament troops stationed at Canons Ashby about the approach of Royalist forces. It is rather curious, therefore, that a portrait of King Charles I is displayed rather prominently in the dining room.

Canons Ashby is a delightful National Trust property. It feels like a family home, but the centuries of its history just ooze from the woodwork.

Maybe you’re a frequent flyer. Maybe not. How many of the flights you have taken were memorable? I hardly remember one flight from another (unless they were the two occasions when I was invited on to the flight-deck, on LH and EK flights, for the landing at Manila (MNL, RPLL). On the other hand, how many airport experiences – good or bad (mostly bad) – have you experienced?

Maybe you’re a frequent flyer. Maybe not. How many of the flights you have taken were memorable? I hardly remember one flight from another (unless they were the two occasions when I was invited on to the flight-deck, on LH and EK flights, for the landing at Manila (MNL, RPLL). On the other hand, how many airport experiences – good or bad (mostly bad) – have you experienced?

Senatus Populusque Romanus –

Senatus Populusque Romanus –

department then as photographer until we moved to Leek 10 years later. In the meantime, my elder brother Edgar had appeared on the scene in July 1946, followed by me a couple of years later. And 13 Moody Street was a ‘tied’ house, opened by the Chronicle’s proprietors, the Head family. In fact, Mr Lionel Head and his wife, who was editor of the Chronicle, lived next door, at No. 15.

department then as photographer until we moved to Leek 10 years later. In the meantime, my elder brother Edgar had appeared on the scene in July 1946, followed by me a couple of years later. And 13 Moody Street was a ‘tied’ house, opened by the Chronicle’s proprietors, the Head family. In fact, Mr Lionel Head and his wife, who was editor of the Chronicle, lived next door, at No. 15.

Despite dominating ‘England’ for only 400 years or so, the legacy of the Roman invasion and conquest of

Despite dominating ‘England’ for only 400 years or so, the legacy of the Roman invasion and conquest of

In many ways the house itself is quite modest. The ground floor entrance hall, library and oak study are open to the public. Access to the first floor is up a beautiful cantilevered staircase. Several bedrooms can be viewed – some of them still used as guest bedrooms! As the house is still lived in, photography is not permitted inside the house.

In many ways the house itself is quite modest. The ground floor entrance hall, library and oak study are open to the public. Access to the first floor is up a beautiful cantilevered staircase. Several bedrooms can be viewed – some of them still used as guest bedrooms! As the house is still lived in, photography is not permitted inside the house.