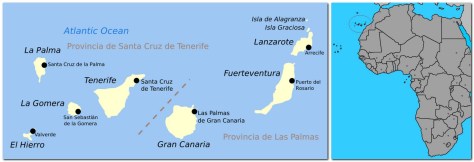

Lying off the Atlantic coast of northwest Africa by less than 600 miles, the Canary Islands archipelago comprises seven large islands, and a small group of islets off the north coast of Lanzarote, the island that lies furthest east and north. Volcanic in origin, and arid for the most part, their flora comprises many interesting endemic species found only on the Atlantic islands of Macaronesia.  I’ve visited the Canaries twice, both in the 1980s, to collect plant germplasm (and also take a family holiday). Both expeditions were funded by the International Board for Plant Genetic Resources (IBPGR, now Bioversity International, based in Rome, Italy). So, as someone who studied potatoes and rice (and some legumes) most of my career, how did I become involved with collecting germplasm in the Canaries?

I’ve visited the Canaries twice, both in the 1980s, to collect plant germplasm (and also take a family holiday). Both expeditions were funded by the International Board for Plant Genetic Resources (IBPGR, now Bioversity International, based in Rome, Italy). So, as someone who studied potatoes and rice (and some legumes) most of my career, how did I become involved with collecting germplasm in the Canaries?

Brian Ford-Lloyd

Searching for beets

After leaving the International Potato Center in March 1981, I arrived at The University of Birmingham to begin my decade-long teaching career as Lecturer in Plant Biology from 1 April. Almost immediately, my colleague and fellow lecturer, Brian Ford-Lloyd (who retired a few years back as Emeritus Professor of Plant Conservation Genetics) invited me to join him on a collecting trip to the Canaries to look for wild relatives of beets (Beta spp.) that would contribute to an IPBGR global initiative on beet germplasm.

Now while I had my own experiences of germplasm collecting of cultivated (and some wild) potatoes in the Andes of South America between 1973 and 1976, I had no experience of beets whatsoever. Brian was keen to have me along on the trip because I did have one very important skill: I spoke (quite) fluent Spanish, and he expected that our Canarian counterparts would speak little English (which turned out to be more or less correct). So, not only would I be an experienced pair of germplasm hands, I could also be interpreter-in-chief.

Fortunately the dates for the trip coincided with my personal timetable then. Having arrived back in the UK at the end of March, my wife Steph (and daughter Hannah) stayed with her parents in Essex while I settled into my new job at the university, and while we house hunted. By the time Brian and I headed off to the Canaries in June, we’d bought our house, but moving in was not scheduled until the first or second weeks of July. So this was a great opportunity for me to join Brian.

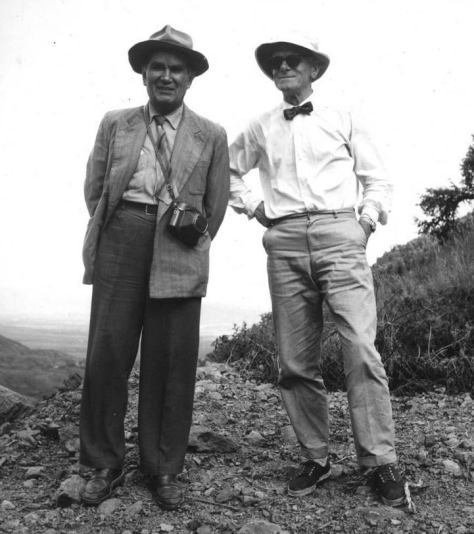

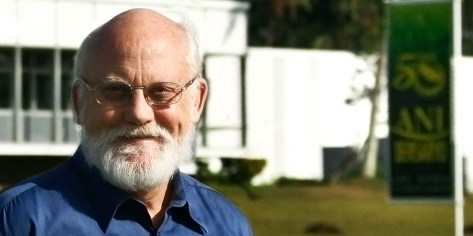

Trevor Williams

Brian completed his PhD in 1973 under the supervision of Trevor Williams, submitting a thesis on the biosystematics of the genus Beta. As part of that research he made a collecting trip throughout Turkey in the early 1970s; and subsequently he maintained his research interest and activity in beets. Collecting in the Canaries was part of an IBPGR global initiative on beets.

Our particular interest there was a group of three beet species of Beta Sect. Patellares (I’m not sure if, or how, the taxonomy of Beta has changed in the intervening years) native to the archipelago, little represented at that time in different germplasm collections. Beets were reported from a range of localities throughout the islands, most often around the coasts or in ruderal habitats, but rarely inland (except in Fuerteventura) where the terrain is too high. In any case, this beet germplasm was considered under threat of genetic erosion, and had to be collected before habitats were lost through expansion of tourist resorts and holiday homes. Brian tells me he has been back to some of the sites where we collected and they have indeed been lost in this way.

Arnoldo Santos-Guerra

Travelling to the Canaries from Elmdon Airport (now Birmingham Airport) via London and Madrid, our first stop was Gran Canaria, staying for a couple of nights at the Jardín Botánico Canario Viera y Clavijo, where British botanist Dr David Bramwell was the director (and his wife Zoë, an acclaimed botanical artist). Those first days were essentially to find our feet, take some advice from David on where best to collect, before heading off to the island of Fuerteventura, the next island east from Gran Canaria, where we would meet our local expert and collaborator, Dr Arnoldo Santos-Guerra of the Centro Regional de Investigación y Tecnología Agrarias, Tenerife. For the collections in Tenerife, La Palma, and La Gomera we were joined by Arnoldo’s colleague, Lic. Manuel Fernández-Galván.

In all, we collected 93 samples of beets from 52 locations on five islands: Gran Canaria, Fuerteventura, Tenerife, La Palma, and La Gomera. Afterwards we published a trip report¹ in the FAO/IBPGR Plant Genetic Resources Newsletter.

On Tenerife, La Palma, and particularly La Gomera, there are precipitous inclines from the main roads down to the ocean’s edge. Deeply dissected landscapes ensure that wild beet populations are isolated from one another, even over relatively short distances as the cliff coastlines project into the ocean, with coves and beaches in between, where beets were often found. Therefore our ability to collect beet samples was quite often dependent entirely upon accessibility to the beach. The photos below were taken in Fuerteventura, Tenerife, and La Gomera. In some of them you can see the level of urbanization, almost 40 years ago, in many localities that were suitable environments for wild beets. The housing and tourist developments must be many times greater today.

But the actual process of collecting was not difficult at all, and seeds were often sampled from most if not all plants in some populations. Wild beets have a prostrate habit, and the ‘seeds’ were often found, in abundance, underneath the living plants. It was then just a question of scooping up handfuls of the seeds into a collecting bag, and annotating the collecting information appropriately.

I say ‘seeds’, but the morphology of beets is a little more complex than that. Actually what we collected were small fruits with a hard pericarp, with several joined together to form multigerm seedballs. Modern sugar beet varieties are monogerm, a trait discovered in a wild beet species, in the former Soviet Union (Ukraine, in fact) during the 1930s . Because of their impermeability to moisture, and also due to the arid environments in which these beets species grew, we were confident that we were collecting viable seeds. In fact, as Brian explained to me, beet seeds are quite difficult to germinate.

On our return to Birmingham, the seeds were added to the Birmingham Beta Collection that Brian curated, and other collections that are part of the World Beta Network. One recipient was Lothar Frese in Germany, now at the Julius Kühn-Institut in Quedlinburg. This germplasm has been used in a variety of studies looking at disease resistance such as Cercospora leaf spot resistance in B. procumbens in particular, and there has been much work since in terms of genetic mapping for resistance. After Brian retired, his beet collection was passed to the Genetic Resources Unit at the Warwick Crop Centre for safe storage.

A beet -‘bean’ linkage

In addition to beets, we collected 11 samples of other crops, among which was just one sample of a shrub or tree fodder legume, tagasaste, from La Palma, classified botanically as Chamaecytisus palmensis, and cultivated by many farmers. In our trip report, referred to above, we commented that the species did seem to be quite variable and, given its wider potential as a fodder legume, we suggested that it would warrant further study.

Javier Francisco-Ortega

And that was the last I thought about tagasaste until six years later when a young Spanish student from Tenerife, Javier Francisco-Ortega, enrolled on the genetic resources MSc course at Birmingham. Thirty years ago this month! I supervised Javier’s MSc dissertation on chromosome variation in Lathyrus pratensis, one of around 150 species in a genus that also contains the commonly-grown garden sweetpea, L. odoratus, and the edible grasspea L. sativus that was one of my research interests during the 1980s.

Anyway, to cut a long story short, Javier was an outstanding student, and began a PhD project with me in October 1988 on the ecogeography of the tagasaste complex, now classified taxonomically as C. proliferus. Only the forms from La Palma are popularly known as tagasaste (the ‘C. palmensis‘ we’d seen in La Palma in 1981), whereas those from the rest of the archipelago are commonly called escobón.

Tagasaste is the only form which is broadly cultivated in the Canary Islands and, since the late 19th century, also in New Zealand and Australia (particularly as fodder for sheep and goats). It has also become naturalized in Australia (South Australia, New South Wales, Victoria and Tasmania), Java, the Hawaiian Islands, California, Portugal, North Africa, Kenya, Tanzania and South Africa.

When I resigned from the university in June 1991 to join the International Rice Research Institute in the Philippines, supervision of Javier’s PhD passed to Brian.

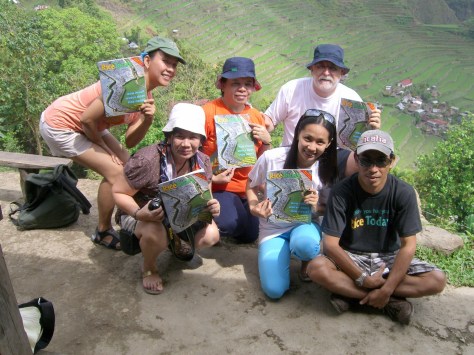

In Spring and Summer 1989, and with funding from IBPGR, Javier began a systematic survey of 184 tagasaste and escobón populations throughout the archipelago (all islands except Fuerteventura and Lanzarote which are too dry), taking herbarium samples from each for morphological study, and revisited later to collect seeds. I joined Javier in July to assist with the collection of seeds from the Tenerife populations. Our trip report² was published in Plant Genetic Resources Newsletter in 1990. Arnoldo Santos-Guerra and Manuel Fernández-Galván were also contributors to this work.

Escobón populations are found commonly growing in gullies among pine forests, and appear to thrive here where there is the ever-present expectation (and danger) of forest fires. Indeed periodic burning appears to support the maintenance of escobón populations. These photos show the habitats of escobón populations in Tenerife, and Javier and myself making collections.

While more common in La Palma, farmers in Tenerife grow a few bushes of tagasaste in their terraces (seen on the right edge of the field in the picture below) on the north-facing slopes of the Teide volcano sloping down to the Atlantic.

We deposited duplicate seed samples in the Spanish national genebank in Madrid, and also in Tenerife. Javier took seeds back to Birmingham for further study, especially for analysis of molecular variation. Besides his PhD thesis, submitted successfully in 1992, his research led to several other scientific papers on morphological variation, phytogeography, ecogeographical characterization, genetic diversity, and the history of origin and distribution.

After he completed his PhD at Birmingham, Javier took postdoctoral fellowships at Ohio State University and the University of Texas at Austin before returning to Tenerife for a couple of years. In 1999 he was appointed Assistant Professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at Florida International University in Miami. He became Full Professor in 2012. He also has a joint appointment at the Fairchild Tropical Garden just south of Miami, as head of the Fairchild Plant Molecular Systematics Laboratory, with a special interest in cycads and palms, as well as an abiding interest in island floras. He has maintained his links with Arnoldo Santos-Guerra and David Bramwell.

In this video, Javier talks about his interests and the impact of his botanical research.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

¹ Ford-Lloyd, B.V., M.T. Jackson & A. Santos Guerra, 1982. Beet germplasm in the Canary Islands. Plant Genetic Resources Newsletter 50, 24-27.

² Francisco-Ortega, F.J., M.T. Jackson, A. Santos-Guerra & M. Fernández-Galván, 1990. Genetic resources of the fodder legumes tagasaste and escobón (Chamaecytisus proliferus (L. fil.) Link sensu lato) in the Canary Islands. Plant Genetic Resources Newsletter 81/82, 27-32.

Well, the short answer is that at the end of October, the last member of my original DPPC team, Zeny Federico, will retire. Others have retired already, moved on to bigger and better things, or moved to other positions in the institute. It’s the end of an era! DPPC no longer exists. Shortly after I retired it changed its name to DRPC—Donor Relations and Project Coordination, and is to become the IRRI Portfolio Management Office (IPMO).

Well, the short answer is that at the end of October, the last member of my original DPPC team, Zeny Federico, will retire. Others have retired already, moved on to bigger and better things, or moved to other positions in the institute. It’s the end of an era! DPPC no longer exists. Shortly after I retired it changed its name to DRPC—Donor Relations and Project Coordination, and is to become the IRRI Portfolio Management Office (IPMO).

And that person was Corinta Guerta, a soil chemist and Senior Associate Scientist working on the adaptation of rice varieties to problem soils. A soil chemist, you might ask? When discussing my new role with Ron Cantrell in early 2001, I’d already mentioned Corinta’s name as someone I would like to try and recruit. What in her experience would qualify Corints (as we know her) to take up a role in donor relations and project management?

And that person was Corinta Guerta, a soil chemist and Senior Associate Scientist working on the adaptation of rice varieties to problem soils. A soil chemist, you might ask? When discussing my new role with Ron Cantrell in early 2001, I’d already mentioned Corinta’s name as someone I would like to try and recruit. What in her experience would qualify Corints (as we know her) to take up a role in donor relations and project management?

When Corints and I interviewed Eric, he quickly understood the essential elements of what we wanted to do, and had potential solutions to hand. Potential became reality! I don’t remember exactly when Eric joined us in DPPC. It must have been around September or October 2001, but within six months we had a functional online grants management system that already moved significantly ahead of where the CIAT system has languished for some time. Our system went from strength to strength and was much admired, envied even, among professionals at the other centers who had similar remits to DPPC.

When Corints and I interviewed Eric, he quickly understood the essential elements of what we wanted to do, and had potential solutions to hand. Potential became reality! I don’t remember exactly when Eric joined us in DPPC. It must have been around September or October 2001, but within six months we had a functional online grants management system that already moved significantly ahead of where the CIAT system has languished for some time. Our system went from strength to strength and was much admired, envied even, among professionals at the other centers who had similar remits to DPPC.

Come October 2015, Yeyet decided to seek pastures new, and joined

Come October 2015, Yeyet decided to seek pastures new, and joined

Nominally the ‘junior’ in DPPC, Vel very quickly became an indispensable member of the team, taking on more responsibilities related to data management. She has a degree in computer science. However, just a month or so back, an opportunity presented itself elsewhere in the institute, and Vel moved to the Seed Health Unit (SHU) as the Material Transfer Agreements Controller. As the SHU is responsible for all imports and exports of rice seeds under the terms of the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture using Material Transfer Agreements, Vel’s role is important to ensure that the institute is compliant under its agreement with FAO for the exchange of rice germplasm. Vel married Jason a few years back, and they have two delightful daughters.

Nominally the ‘junior’ in DPPC, Vel very quickly became an indispensable member of the team, taking on more responsibilities related to data management. She has a degree in computer science. However, just a month or so back, an opportunity presented itself elsewhere in the institute, and Vel moved to the Seed Health Unit (SHU) as the Material Transfer Agreements Controller. As the SHU is responsible for all imports and exports of rice seeds under the terms of the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture using Material Transfer Agreements, Vel’s role is important to ensure that the institute is compliant under its agreement with FAO for the exchange of rice germplasm. Vel married Jason a few years back, and they have two delightful daughters. Inspector General at FAO in Rome for six years from February 2010), and whose office was just down the corridor from mine, we decided to develop a bottom-up approach, but needed a safe pair of hands to manage this full-time. So we hired Alma Redillas Dolot as a consultant, and she stayed with DPPC for a couple of years before joining the IAU.

Inspector General at FAO in Rome for six years from February 2010), and whose office was just down the corridor from mine, we decided to develop a bottom-up approach, but needed a safe pair of hands to manage this full-time. So we hired Alma Redillas Dolot as a consultant, and she stayed with DPPC for a couple of years before joining the IAU.

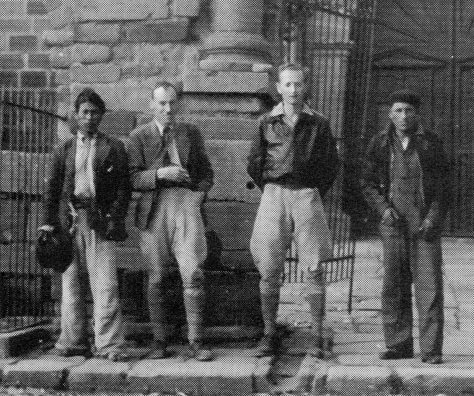

The first week of October 1967. 50 years ago, to the day and date. Monday 2 October.

The first week of October 1967. 50 years ago, to the day and date. Monday 2 October.

I had a room on the sixth floor, with a view overlooking Woodmill Lane to the west, towards the university, approximately 1.2 miles and 25 minutes away on foot. In the next room to mine, or perhaps two doors away, I met John Grainger who was also signed up for the same course as me. John had grown up in Kenya where his father worked as an entomologist. Now that sounded quite exotic to me.

I had a room on the sixth floor, with a view overlooking Woodmill Lane to the west, towards the university, approximately 1.2 miles and 25 minutes away on foot. In the next room to mine, or perhaps two doors away, I met John Grainger who was also signed up for the same course as me. John had grown up in Kenya where his father worked as an entomologist. Now that sounded quite exotic to me.

Rice is such a fascinating crop you might want to understand a little more. And there’s no better source than Rice Today, a magazine launched by the

Rice is such a fascinating crop you might want to understand a little more. And there’s no better source than Rice Today, a magazine launched by the

I am leading the evaluation of an international genebanks program, part of the portfolio of the

I am leading the evaluation of an international genebanks program, part of the portfolio of the

I’m a bit of a news junkie, so I’ve been avidly following presidential election campaigns in three countries in online newspapers and on social media.

I’m a bit of a news junkie, so I’ve been avidly following presidential election campaigns in three countries in online newspapers and on social media. Back home in my digs¹, I was taking it easy, feeling sorry for myself, with a very sore mouth indeed. I’d been listening to a folk music program on the radio. I don’t remember the actual details. What I do remember very clearly about that afternoon, however, was listening to what must have been a pre-release of a beautiful track, Lovely on the water, from the second album (

Back home in my digs¹, I was taking it easy, feeling sorry for myself, with a very sore mouth indeed. I’d been listening to a folk music program on the radio. I don’t remember the actual details. What I do remember very clearly about that afternoon, however, was listening to what must have been a pre-release of a beautiful track, Lovely on the water, from the second album (

Now Steeleye Span only formed in 1969, but two of the members were Tim Hart and Maddy Prior who sang at the Folk Club quite frequently over the three years I was in Southampton. They were quite popular on the folk circuit, and had released two well-received

Now Steeleye Span only formed in 1969, but two of the members were Tim Hart and Maddy Prior who sang at the Folk Club quite frequently over the three years I was in Southampton. They were quite popular on the folk circuit, and had released two well-received

And it wasn’t long before his presence was felt. It’s not inappropriate to comment that IRRI had lost its way during the previous decade for various reasons. There was no clear research strategy nor direction. Strong leadership was in short supply. Bob soon put an end to that, convening an international expert group of stakeholders (rice researchers, rice research leaders from national programs, and donors) to help the institute chart a perspective for the next decade or so. In 2006 IRRI’s Strategic Plan (2007-2015),

And it wasn’t long before his presence was felt. It’s not inappropriate to comment that IRRI had lost its way during the previous decade for various reasons. There was no clear research strategy nor direction. Strong leadership was in short supply. Bob soon put an end to that, convening an international expert group of stakeholders (rice researchers, rice research leaders from national programs, and donors) to help the institute chart a perspective for the next decade or so. In 2006 IRRI’s Strategic Plan (2007-2015),