I’m a contented atheist. And have been since I was nineteen. However, I was baptized a Catholic, but never practiced until my family moved to Leek in 1956.

A little background. My mother’s family were Irish Catholics. My father’s parents were Methodist. My parents were married at St. Joseph’s Roman Catholic Church, Epsom, Surrey in November 1936. But as I grew up in Congleton (where I was born in 1948), I have only one recollection of ever having stepped inside the Church of St Mary on West Road. I remember my mother once telling me about an incident at the church, maybe when my sister took her First Communion. Apparently, the parish priest told my mother that my father, a Protestant, was not welcome in the church. No ecumenism in those post-war days. So until we moved to Leek in 1956, I can never remember going to Mass.

St Mary’s Church on Compton in the 1950s/60s, from the bottom of St Edward Street where we lived.

Things changed after the move to Leek, and we started to attend Mass at St Mary’s Catholic church. I even trained as an altar boy, alongside Michael Oliver (brother of Kevin, whose father kept a sweet shop on Broad Street). Not infrequently I’d accompany one of the priests to say Mass in Ipstones (at a pub there) or St Edward’s Hospital in Cheddleton. I joined the cub scouts, 5th Leek St Mary’s, run by Mr Kelsall, who we called ‘Sir’ instead of ‘Akela’.

The parish priest was Fr Clavin – liked by many who came in contact with him. Fr Thornton was the curate when we moved to Leek, but he was soon replaced by another younger priest, on the left of the photo below. This photo was taken on the occasion of Fr Clavin’s Jubilee (with a young Gerald Grant on the right).

My elder brother Edgar and I were also enrolled in the local Catholic primary school, St Mary’s, on the corner of Broad Street (the A53) and Cruso Street. Being two years older (and three academic years ahead), Edgar attended St Mary’s for just one year. I, on the other hand, continued my education there until July 1960 when I secured a place to attend the Catholic grammar school, St Joseph’s College, in Trent Vale, Stoke-on-Trent, which entailed a round trip of 28 miles. That became my daily term-time routine for the next seven years.

April 1956. I was 7½.

New town, new friends, new school . . . and NUNS!

I think I must have shed a few tears that first day at school. I was so bewildered. I’d never seen a nun before, and they looked so intimidating in their long black habits, white wimples leaving just their faces exposed, and long black veils typical of the Sisters of Loreto, who came to Leek in 1860 to teach children of the parish. The last nuns left in 1980, and their convent behind the church was sold for development.

St Mary’s Infants School, Selbourne Road in the 1960s

The headmistress, Mother Michael seemed quite pleasant and welcoming, but she left after about a year. In the four years I spent at St Mary’s my teachers were Mother Bernadine, Mother Elizabeth (who became headmistress) and, in my last year, Mr Smith (the first male teacher at the school). Sister (later Mother) Martin and Mother Vincent de Paul were other teachers who I remember.

My wife still uses a woven needle/pin case that I made during my time at St Mary’s (helped by one of the teachers).

So what’s all this about losing my religion? Well, a few days ago, I posted a query on the closed group Facebook page about Leek to which I belong. I was researching some information (and photographs) for a blog post I intend publishing a little later this year. While my query yielded few photos, I was surprised at the number of people who joined the conversation. And for many, their years at St Mary’s were not the happiest.

I always saw the nuns as quite strict. One of them often used the edge of a steel-edged ruler to rap any miscreant on the knuckles. It didn’t take much to be viewed as a miscreant, as the Facebook commentaries from former pupils indicate.

Some were clearly profoundly unhappy at St Mary’s, others not. Some have recounted being caned in front of the whole school, even for attending a wedding at a non-Catholic church! All in all, I was quite horrified at these memories of what seem like gratuitous violence perpetrated on 5-11 year-olds. The situation for several was so dire, apparently, that they were moved by their parents to another non-Catholic school in the town.

I never saw any canings, or at least I don’t remember the cane being administered. Until some of the Facebook group members mentioned this, it didn’t form part of my memory narrative. The ruler I certainly do remember and was the recipient on at least one occasion.

On the whole, my memories of just over four years at St Mary’s are neither positive nor negative. As one group member stated overnight, we survived. But was that sufficient?

Things have changed. Take a look at the St Mary’s today; it appears to be a thriving and nurturing community.

Corporal punishment was a daily occurrence at St Joseph’s, especially for pupils younger than sixteen. Punishments were meted out almost every lesson, even for slight misdemeanors.

The school, for boys only, had been founded by Irish Christian Brothers in the 1930s. I guess that when I first attended the Brothers were about a fifth of the teaching staff. Or maybe I exaggerate. Certainly walking around in their long black cassocks and dog collars they were a highly identifiable presence who brooked no dissension.

Today the Christian Brothers are no longer associated with St Joseph’s. It’s also co-educational, and has a thriving Sixth Form that attracts students from the wider community, Catholics and non-Catholics alike.

In 1960, the headmaster was Bro. Henry Wilkinson (for a couple of years) and thereafter until I left in 1967, Bro. O’Keefe. Bro. Wilkinson regularly used a tannoy to broadcast to every classroom throughout the school, which was quickly dismantled after O’Keefe took the reins.

Every teacher was permitted to physically punish any pupil, and used a leather strap (apparently manufactured in Ireland), maybe almost 18 inches long, of at least two layers of leather sewed together.

The Brothers had a special pocket in the side of their cassocks to hold the strap. Usually, a boy would hold out one of both hands, palm upwards, and receive maybe a couple of strokes. It hurt! It also depended on which teacher was administering the strap. Some were more ‘effective’ than others. During my first four years at St Joseph’s I received my fair share of strappings, and there was a memorable one during Year 4.

My home class teacher was Mr Joyce (first name unknown or not remembered) who taught French. During Year 3 I had represented the school in an inter-school quiz broadcast to the local hospitals. We lost in the Final to a local girls’ grammar school!

Anyway, one afternoon, Mr Joyce explained that he would hold a quiz to identify promising candidates for the next season’s team. Since I’d already participated, I didn’t take this seriously, and started chatting with the person next to me. We had double desk. Joyce warned me twice to stop talking, but I persisted. On the third warning, he took out his strap, told me to hold out my hand, reached across the desk, and hit me twice across the palm on that fleshy part just below the thumb.

Yes, it hurt but not unduly. However, as I reached for my pen, I suddenly felt dizzy, and the next thing I found myself trying to drag myself off the floor. I’d passed out, and as I fell off my seat, hit my head on the wall to the side. My classmates were shocked. Needless to say, Mr Joyce never touched me again.

We took corporal punishment for granted. Did it have any lasting effect? Probably not for the majority of pupils. But you can never deny that for some of us, it was unduly cruel.

However, it was this flagrant recourse to corporal punishment that lead to me rejecting Catholicism, indeed any formal religion.

When I was in the Upper Sixth (the year immediately prior to heading off to university), Brother Baylor joined the staff (maybe a year earlier). But I’d had no contact with him until then. Anyway, he took us for a formal religion study period once or twice a week. On this particular day, in he came to the classroom and, struggling to peer over his desk (he was a tiny man), told us that we would be doing some Bible studies that day. And, removing his leather strap from its ‘holster’, and lightly tapping it across his hand, told us in a threatening tone, that we would believe else he would strap us.

It was like a light bulb going off in my head. I realized that if a ‘man of God’ had to make threats such as this, there couldn’t be much to sustain the foundation of his beliefs. And from that day I refused to attend Sunday Mass; I went through the motions at school as there were services we had to attend. I’ve not been to Mass since, and never will. The Catholic Church lost one of its flock. I guess I started out as agnostic, but this has become hardened over the years into contented atheism.

As I mentioned earlier, I was quite horrified to read those sad commentaries about St Mary’s. It’s not a situation I recognize since I did not experience it. It’s as though the nuns had Jekyll and Hyde personalities. That does not however diminish the impact of those unhappy years on some members of the St Mary’s community in the 1950s and 60s.

This feedback comes at a time when the Catholic Church is under ever closer scrutiny not only about child sex abuse, but also wider abuse of children for which some of the incidents related on that Facebook page might legitimately be considered. If not abuse as such, it was certainly bordering on abuse in my opinion. ‘Official’ violence against small children would not be tolerated in schools today. Yes, it was another era but that should not, and cannot, excuse such behavior.

I moved on. I’ve had a fruitful career and happy life. But a simple Facebook request has brought so many memories flooding back, not only for me but all those who read it, that I could not pass another day without committing my thoughts in this post.

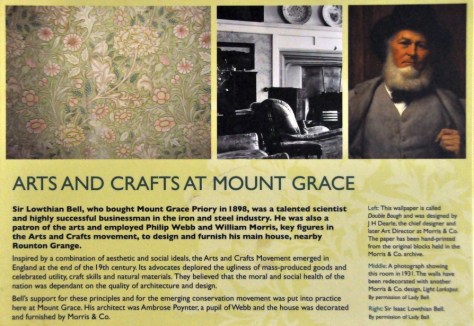

Sitting atop 136 m Penshaw Hill, dominating the surrounding landscape and visible for miles, Penshaw Monument is quite an icon in the northeast of England, on the southwest outskirts of Sunderland (map).

Sitting atop 136 m Penshaw Hill, dominating the surrounding landscape and visible for miles, Penshaw Monument is quite an icon in the northeast of England, on the southwest outskirts of Sunderland (map).

Nestling under the Cleveland Hills in North Yorkshire, about half way between Thirsk and Middlesbrough along the A19 (

Nestling under the Cleveland Hills in North Yorkshire, about half way between Thirsk and Middlesbrough along the A19 (

I was searching YouTube the other day for videos about the recent 5th International Rice Congress held in Singapore, when I came across several on the

I was searching YouTube the other day for videos about the recent 5th International Rice Congress held in Singapore, when I came across several on the

But it’s Remain supporters who are getting plucked and stuffed.

But it’s Remain supporters who are getting plucked and stuffed. Short-sighted, except one, perhaps.

Short-sighted, except one, perhaps.

materials, among others. You can check the status of the IRRI collection (and many more genebanks in the

materials, among others. You can check the status of the IRRI collection (and many more genebanks in the

In 1981, one of the students attending the one-year

In 1981, one of the students attending the one-year  Today, the

Today, the  Yesterday, I was reminded of that great radio broadcaster,

Yesterday, I was reminded of that great radio broadcaster,  Steph and I took full advantage to walk a stretch of

Steph and I took full advantage to walk a stretch of

I strongly support the demand for a

I strongly support the demand for a

We chose a small studio cottage, suitable for a couple, just north of Helston on the south coast, a round trip of more than 500 miles (including the side trips to a couple of National Trust properties on the way there and back – see

We chose a small studio cottage, suitable for a couple, just north of Helston on the south coast, a round trip of more than 500 miles (including the side trips to a couple of National Trust properties on the way there and back – see

I have the Brexit blues.

I have the Brexit blues.

My son-in-law, Michael, is – like me – a beer aficionado, and keeps a well-stocked cellar of many different beers. It’s wonderful to see how the beer culture has blossomed in the USA, no longer just Budweiser or Coors. I had opportunity to enjoy a variety of beers. Those IPAs are so good, if not a little hoppy sometimes. However, my 2018 favorite was a Czech-style pilsener,

My son-in-law, Michael, is – like me – a beer aficionado, and keeps a well-stocked cellar of many different beers. It’s wonderful to see how the beer culture has blossomed in the USA, no longer just Budweiser or Coors. I had opportunity to enjoy a variety of beers. Those IPAs are so good, if not a little hoppy sometimes. However, my 2018 favorite was a Czech-style pilsener,