There was a germplasm-fest taking place earlier this week, high above the Arctic Circle.

The Svalbard Global Seed Vault celebrated 10 years and, accepting new seed samples from genebanks around the world (some new, some adding more samples to those already deposited) brought the total to more than 1 million sent there for safe-keeping since it opened in February 2008. What a fantastic achievement!

Establishment of the Svalbard Global Seed Vault really does represent an extraordinary—and unprecedented—contribution by the Norwegian government to global efforts to conserve plant genetic resources for food and agriculture. Coinciding with the tenth anniversary, the Norwegian government also announced plans to contribute a further 100 million Norwegian kroner (about USD13 million) to upgrade the seed vault and its facilities. Excellent news!

An interesting article dispelling a few myths about the vault was published in The Washington Post on 26 February.

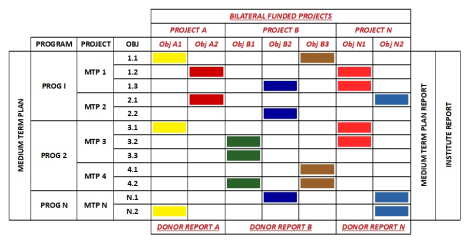

The CGIAR genebank managers also met in Svalbard, and there was the obligatory visit to the seed vault.

Genebank managers from: L-R front row: ICRAF, Bioversity International, and CIAT, CIAT; and standing, L-R: CIMMYT, ILRI, IITA, ICRISAT, IRRI, ??, CIP, ??, Nordgen, ICRAF

Several of my former colleagues from six genebanks and Cary Fowler (former director of the Crop Trust) were recognized by the Crop Trust with individual Legacy Awards.

Crop Trust Legacy Awardees, L-R: Dave Ellis (CIP), Hari Upadhyaya (ICRISAT), Ruaraidh Sackville Hamilton (IRRI), Daniel Debouck (CIAT), Ahmed Amri (ICARDA), Cary Fowler (former Director of the Crop Trust). and Jean Hanson (ILRI). Photo courtesy of the Crop Trust.

This timely and increased focus on the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, celebrities getting in on the act, and HRH The Prince of Wales hosting (as Global Patron of the Crop Trust) a luncheon and meeting at Clarence House recently, help raise the profile of safeguarding genetic diversity. The 10th anniversary of the Svalbard vault was even an item on BBC Radio 4’s flagship Today news program this week. However, this is no time for complacency.

We need genebanks

The management and future of genebanks have been much on my mind over the past couple of years while I was leading an evaluation of the CGIAR’s research support program on Managing and Sustaining Crop Collections (otherwise known as the Genebanks CRP, and now replaced by its successor, the Genebank Platform). On the back of that review, and reading a couple of interesting genebank articles last year [1], I’ve been thinking about the role genebanks play in society, how society can best support them (assuming of course that the role of genebanks is actually understood by the public at large), and how they are funded.

Genebanks are important.  However, don’t just believe me. I’m biased. After all, I dedicated much of my career to collect, conserve, and use plant genetic resources for the benefit of humanity. Genebanks and genetic conservation are recognized in the Zero Hunger Goal 2: End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture of the United Nation’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals.

However, don’t just believe me. I’m biased. After all, I dedicated much of my career to collect, conserve, and use plant genetic resources for the benefit of humanity. Genebanks and genetic conservation are recognized in the Zero Hunger Goal 2: End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture of the United Nation’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals.

There are many examples showing how genebanks are the source of genes to increase agricultural productivity or resilience in the face of a changing climate, reduce the impact of diseases, and enhance the nutritional status of the crops that feed us.

In the fight against human diseases too I recently heard an interesting story on the BBC news about the antimicrobial properties of four molecules, found in Persian shallots (Allium hirtifolium), effective against TB antibiotic-resistance. There’s quite a literature about the antimicrobial properties of this species, which is a staple of Iranian cuisine. Besides adding to agricultural potential, just imagine looking into the health-enhancing properties of the thousands and thousands of plant species that are safely conserved in genebanks around the world.

Yes, we need genebanks, but do we need quite so many? And if so, can we afford them all? What happens if a government can longer provide the appropriate financial support to manage a genebank collection? Unfortunately, that’s not a rhetorical question. It has happened. Are genebanks too big (or too small) to fail?

Too many genebanks?

According to The Second Report on The State of the World’s Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture published by FAO in 2010, there are more than 1700 genebanks/genetic resources collections around the world. Are they equally important, and are their collections safe?

Fewer than 100 genebanks/collections have so far safeguarded their germplasm in the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, just 5% or so, but among them are some of the largest and most important germplasm collections globally such as those in the CGIAR centers, the World Vegetable Center in Taiwan, and national genebanks in the USA and Australia, to name but a few.

I saw a tweet yesterday suggesting that 40% of the world’s germplasm was safely deposited in Svalbard. I find figure that hard to believe, and is more likely to be less than 20% (based on the estimate of the total number of germplasm accessions worldwide reported on page 5 of this FAO brief). I don’t even know if Svalbard has the capacity to store all accessions if every genebank decided to deposit seeds there. In any case, as explained to me a couple of years ago by the Svalbard Coordinator of Operation and Management, Åsmund Asdal, genebanks must meet several criteria to send seed samples to Svalbard. The criteria may have been modified since then. I don’t know.

First, samples must be already stored at a primary safety back-up site; Svalbard is a ‘secondary’ site. For example, in the case of the rice collection at IRRI, the collection is duplicated under ‘black-box’ conditions in the vaults of the USDA’s National Lab for Genetic Resources Preservation in Fort Collins, Colorado, and has been since the 1980s.

The second criterion is, I believe, more difficult—if not almost impossible—to meet. Apparently, only unique samples should be sent to Svalbard. This means that the same sample should not have been sent more than once by a genebank or, presumably, by another genebank. Therein lies the difficulty. Genebanks exchange germplasm samples all the time, adding them to their own collections under a different ID. Duplicate accessions may, in some instances, represent the bulk of germplasm samples that a genebank keeps. However, determining if two samples are the same is not easy; it’s time-consuming, and can be expensive. I assume (suspect) that many genebanks just package up their germplasm and send it off to Svalbard without making these checks. And in many ways, provided that the vault can continue to accept all the possible material from around the world, this should not be an issue. It’s more important that collections are safe.

Incidentally, the current figure for Svalbard is often quoted in the media as ‘1 million unique varieties of crops‘. Yes, 1 million seed samples, but never 1 million varieties. Nowhere near that figure.

In the image below, Åsmund is briefing the press during the vault’s 10th anniversary.

Svalbard is a very important global repository for germplasm, highlighted just a couple of years ago or so when ICARDA, the CGIAR center formerly based in Aleppo, Syria was forced to relocate (because of the civil war in that country) and establish new research facilities—including the genebank—in Lebanon and Morocco. Even though the ICARDA crop collections were already safely duplicated in other genebanks, Svalbard was the only location where they were held together. Logistically it was more feasible to seek return of the seeds from Svalbard rather than from multiple locations. This was done, germplasm multiplied, collections re-established in Morocco and Lebanon, and much has now been returned to Svalbard for safe-keeping once again. The seed vault played the role that was intended. To date, the ICARDA withdrawal of seeds from Svalbard has been the only one.

However, in terms of global safety of all germplasm, blackbox storage at Svalbard is not an option for all crops and their wild relatives. Svalbard can only provide safe storage for seeds that survive low temperatures. There are many species that have short-lived seeds that do not tolerate desiccation or low temperature storage, or which reproduce vegetatively, such as potatoes through tubers, for example. Some species are kept as in vitro or tissue culture collections as shown in the images below for potatoes at CIP (top) or cassava at CIAT (below).

Some species can be cryopreserved at the temperature of liquid nitrogen, and is a promising technology for potato at CIP.

I believe discussions are underway to find a global safety back-up solution for these crops.

How times have changed

Fifty years ago, there was a consensus (as far as I can determine from different publications) among the pioneer group of experts (led by Sir Otto Frankel) that just a relatively small network of international and regional genebanks, and some national ones, was all that would be needed to hold the world’s plant genetic resources. How times have changed!

Sir Otto Frankel and Ms Erna Bennett

In one of the first books dedicated to the conservation and use of plant genetic resources [2], Sir Otto and Erna Bennett wrote: A world gene bank may be envisaged as an association of national or regional institutions operating under international agreements relating to techniques and the availability of material, supported by a central international clearing house under the control of an international agency of the United Nations. Regional gene banks which have been proposed could make a contribution provided two conditions are met—a high degree of technical efficiency, and unrestricted international access. It is of the greatest importance that both these provisos are secured; an international gene bank ceases to fulfil its proper function if it is subjected to national or political discrimination. In the light of subsequent developments, this perspective may be viewed as rather naïve perhaps.

Everything changed in December 1993 when the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) came into force. Until then, plant genetic resources for food and agriculture had been viewed as the ‘heritage of mankind’ or ‘international public goods’. Individual country sovereignty over national genetic resources became, appropriately, the new norm. Genebanks were set up everywhere, probably with little analysis of what that meant in terms of long-term security commitments or a budget for maintaining, evaluating, and using these genebank collections. When I was active in genebank management during the 1990s, and traveling around Asia, I came across several examples where ‘white elephant’ genebanks had been built, operating on shoe-string budgets, and mostly without the resources needed to maintain their collections. It was not uncommon to come across genebanks without the resources to maintain the integrity of the cold rooms where seeds were stored.

Frankel and Bennett further stated that: . . . there is little purpose in assembling material unless it is effectively used and preserved. The efficient utilization of genetic resources requires that they are adequately classified and evaluated. This statement still has considerable relevance today. It’s the raison d’être for genetic conservation. As we used to tell our genetic resources MSc students at Birmingham: No conservation without use!

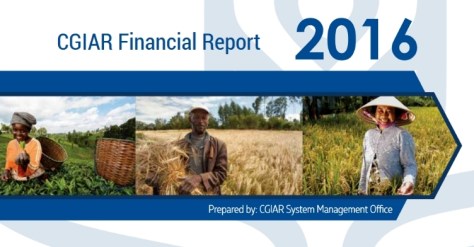

The 11 genebanks of the CGIAR meet the Frankel and Bennet criteria and are among the most important in the world, in terms of: the crop species and wild relatives conserved [3]; the genebank collection size (number of accessions); their remarkable genetic diversity; the documentation and evaluation of conserved germplasm; access to and exchange of germplasm (based on the number of Standard Material Transfer Agreements or SMTAs issued each year); the use of germplasm in crop improvement; and the quality of conservation management, among others. They (mostly) meet internationally-agreed genebank standards.

For what proportion of the remaining ‘1700’ collections globally can the same be said? Many certainly do; many don’t! Do many national genebanks represent value for money? Would it not be better for national genebanks to work together more closely? Frankel and Bennett mentioned regional genebanks, that would presumably meet the conservation needs of a group of countries. Off the top of my head I can only think of two genebanks with a regional mandate. One is the Southern African Development Community (SADC) Plant Genetic Resource Centre, located in Lusaka, Zambia. The other is CATIE in Turrialba, Costa Rica, which also maintains collections of coffee and cacao of international importance.

The politics of genetic conservation post-1993 made it more difficult, I believe, to arrive at cooperative agreements between countries to conserve and use plant genetic resources. Sovereignty became the name of the game! Even among the genebanks of the CGIAR it was never possible to rationalize collections. Why, for example, should there be two rice collections, at IRRI and Africa Rice, or wheat collections at CIMMYT and ICARDA? However, enhanced data management systems, such as GRIN-Global and Genesys, are providing better linkages between collections held in different genebanks.

Meeting the cost

The International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture provides the legal framework for supporting the international collections of the CGIAR and most of the species they conserve.

The International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture provides the legal framework for supporting the international collections of the CGIAR and most of the species they conserve.

Running a genebank is expensive. The CGIAR genebanks cost about USD22 million annually to fulfill their mandates. It’s not just a case of putting seed packets in a large refrigerator (like the Svalbard vault) and forgetting about them, so-to-speak. There’s a lot more to genebanking (as I highlighted here) that the recent focus on Svalbard has somewhat pushed into the background. We certainly need to highlight many more stories about how genebanks are collecting and conserving genetic resources, what it takes to keep a seed accession or a vegetatively-propagated potato variety, for example, alive and available for generations to come, how breeders and other scientists have tapped into this germplasm, and what success they have achieved.

Until the Crop Trust stepped in to provide the security of long-term funding through its Endowment Fund, these important CGIAR genebanks were, like most national genebanks, threatened with the vagaries of short-term funding for what is a long-term commitment. In perpetuity, in fact!

Until the Crop Trust stepped in to provide the security of long-term funding through its Endowment Fund, these important CGIAR genebanks were, like most national genebanks, threatened with the vagaries of short-term funding for what is a long-term commitment. In perpetuity, in fact!

Many national genebanks face even greater challenges and the dilemma of funding these collections has not been resolved. Presumably national genebanks should be the sole funding responsibility of national governments. After all, many were set up in response to the ‘sovereignty issue’ that I described earlier. But some national collections also have global significance because of the material they conserve.

I’m sure that genebank funding does not figure prominently in government budgets. They are a soft target for stagflation and worse, budget cuts. Take the case of the UK for instance. There are several important national collections, among which the UK Vegetable Genebank at the Warwick Crop Centre and the Commonwealth Potato Collection at the James Hutton Institute in Scotland figure prominently. Consumed by Brexit chaos, and despite speaking favorably in support of biodiversity at the recent Clarence House meeting that I mentioned earlier in this post, I’m sure that neither of these genebanks or others is high on the agenda of Secretary of State for Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), Michael Gove MP or his civil servants. If a ‘wealthy’ country like the UK has difficulties finding the necessary resources, what hope have resource-poorer countries have of meeting their commitments.

However, a commitment to place their germplasm in Svalbard would be a step in the right direction.

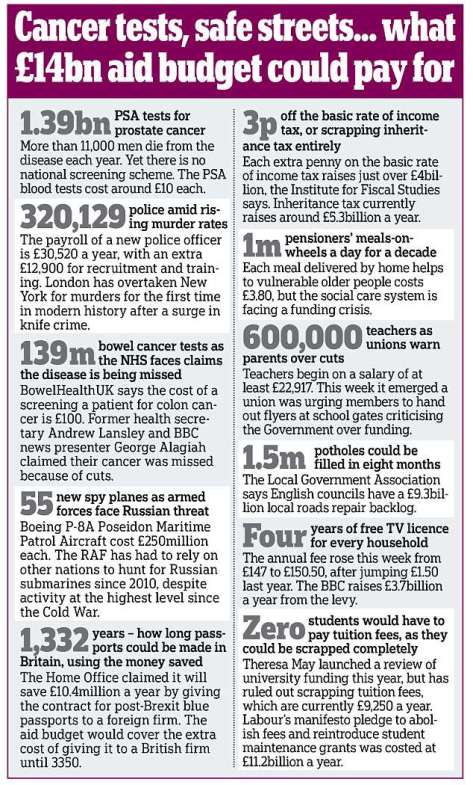

I mentioned that genebanking is expensive, yet the Crop Trust estimates that an endowment of only USD850 million would provide sufficient funding in perpetuity to support the genebanks. USD850 million seems a large sum, yet about half of this has already been raised as donations, mostly from national governments that already provide development aid. In the UK, with the costs of Brexit becoming more apparent day-by-day, and the damage that is being done to the National Health Service through recurrent under-funding, some politicians are now demanding changes to the government’s aid budget, currently at around 0.7% of GDP. I can imagine the consequences for food security in nations that depend on such aid, were it reduced or (heaven help us) eliminated.

On the other hand, USD850 million is peanuts. Take the cost of one A380 aircraft, at around USD450 million. Emirates Airlines has just confirmed an order for a further 36 aircraft!

The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation continues to do amazing things through its generous grants. A significant grant from the BMGF could top-up the Endowment Fund. The same goes for other donor agencies.

Let’s just do it and get it over with.

Then we can get on with the job of not only making all germplasm safe, especially for species that are hard to or cannot be conserved as seeds, but by using the latest ‘omics’ technologies [4] to understand just how germplasm really is the basis of food security for everyone on this beautiful planet of ours.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

[1] One, on the Agricultural Biodiversity Weblog (that is maintained by two friends of mine, Luigi Guarino, the Director of Science and Programs at the Crop Trust in Bonn, and Jeremy Cherfas, formerly Senior Science Writer at Bioversity International in Rome and now a Freelance Communicator) was about accounting for the number of genebanks around the world. The second, published in The Independent on 2 July 2017, was a story by freelance journalist Ashley Coates about the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, and stated that it is ‘the world’s most important freezer‘.

[2] Frankel, OH and E Bennett (1970). Genetic resources. In: OH Frankel and E Bennett (eds) Genetic Resources in Plants – their Exploration and Conservation. IBP Handbook No 11. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford and Edinburgh.

[2] Frankel, OH and E Bennett (1970). Genetic resources. In: OH Frankel and E Bennett (eds) Genetic Resources in Plants – their Exploration and Conservation. IBP Handbook No 11. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford and Edinburgh.

[3] The CGIAR genebanks hold major collections of farmer varieties and wild relatives of crops that feed the world’s population on a daily basis: rice, wheat, maize, sorghum and millets, potato, cassava, sweet potato, yam, temperate and tropical legume species like lentil, chickpea, pigeon pea, and beans, temperate and tropical forage species, grasses and legumes, that support livestock, and fruit and other tree species important in agroforestry systems, among others.

[4] McNally, KL, 2014. Exploring ‘omics’ of genetic resources to mitigate the effects of climate change. In: M Jackson, B Ford-Lloyd and M Parry (eds). Plant Genetic Resources and Climate Change. CABI, Wallingford, Oxfordshire. pp.166-189 (Chapter 10).

William Tecumseh Sherman. Red-haired. Union Major-General in the American Civil War. Outstanding military strategist. Commander of the Army of the Tennessee. Mastermind of the March to the Sea (that culminated in the capture of Savannah, GA) and the Carolinas Campaign, both of which contributed significantly to the end of the Civil War in 1865.

William Tecumseh Sherman. Red-haired. Union Major-General in the American Civil War. Outstanding military strategist. Commander of the Army of the Tennessee. Mastermind of the March to the Sea (that culminated in the capture of Savannah, GA) and the Carolinas Campaign, both of which contributed significantly to the end of the Civil War in 1865.

Despite its incredibly bloody outcomes and destructive consequences, the American Civil War, 1861-65 holds a certain fascination. To a large extent, it was the first war to be extensively documented photographically, many of the images coming from the lens of Mathew Brady.

Despite its incredibly bloody outcomes and destructive consequences, the American Civil War, 1861-65 holds a certain fascination. To a large extent, it was the first war to be extensively documented photographically, many of the images coming from the lens of Mathew Brady.

takes some getting used to. I now understand that unless it specifically states not to turn, it’s OK to make that turn. Not something we’re used to in the UK. Red means red! And also, having to be aware that if you turn right on a red light, there may be pedestrians crossing as they will have right of way.

takes some getting used to. I now understand that unless it specifically states not to turn, it’s OK to make that turn. Not something we’re used to in the UK. Red means red! And also, having to be aware that if you turn right on a red light, there may be pedestrians crossing as they will have right of way.

I’m almost 70, yet, when buying a couple of cases of beer at Target in St Paul recently, I was asked for my ID! Fortunately the lady at the checkout was from Scandinavia (and had lived in the UK for several years) so recognized my UK photo driving licence. She told me that normally it would have to be a US or Canadian driving licence or passport. Good grief, 70 years old and having to present a passport just to buy a beer! And then there was $2.36 sales tax to add to the offer of $25 for two cases that had attracted my attention.

I’m almost 70, yet, when buying a couple of cases of beer at Target in St Paul recently, I was asked for my ID! Fortunately the lady at the checkout was from Scandinavia (and had lived in the UK for several years) so recognized my UK photo driving licence. She told me that normally it would have to be a US or Canadian driving licence or passport. Good grief, 70 years old and having to present a passport just to buy a beer! And then there was $2.36 sales tax to add to the offer of $25 for two cases that had attracted my attention.

Just north of the state line we took a short detour to

Just north of the state line we took a short detour to

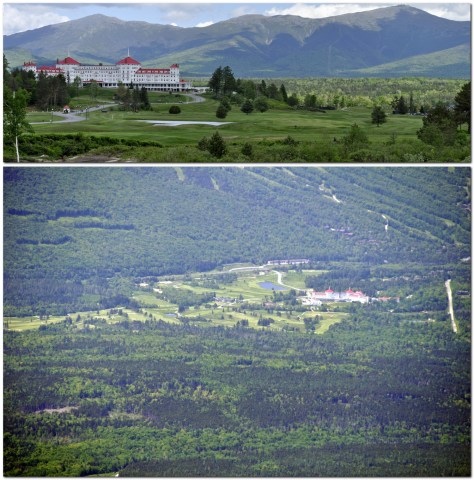

There was a glorious view south from Whitcomb Summit, and some miles further on, just short of North Adams, there is a spectacular view north into southern Vermont, reminding us of the views we saw when exploring the

There was a glorious view south from Whitcomb Summit, and some miles further on, just short of North Adams, there is a spectacular view north into southern Vermont, reminding us of the views we saw when exploring the

The

The  The RHS Malvern Spring Festival is the second in the Society’s 2018 calendar and, set against the magnificent Malvern Hills . . . is packed with flowers, food, crafts and family fun. And yes, we did have fun. So rather than describe what we did and saw, here’s just a selection of the many photos I took during the day.

The RHS Malvern Spring Festival is the second in the Society’s 2018 calendar and, set against the magnificent Malvern Hills . . . is packed with flowers, food, crafts and family fun. And yes, we did have fun. So rather than describe what we did and saw, here’s just a selection of the many photos I took during the day.

It’s not my intention here to provide a detailed history of Rievaulx Abbey. English Heritage owns and manages the site, and a detailed history of Rievaulx’s founding and growth can be found on its

It’s not my intention here to provide a detailed history of Rievaulx Abbey. English Heritage owns and manages the site, and a detailed history of Rievaulx’s founding and growth can be found on its

All four centers are members of the

All four centers are members of the

In 1969, World Bank President Robert McNamara (who had been US Secretary of Defense under Presidents Kennedy and Johnson) wrote to the heads of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) in Rome and the United Nations Development Fund (UNDP) in New York saying: I am writing to propose that the FAO, the UNDP and the World Bank jointly undertake to organize a long-term program of support for regional agricultural research institutes. I have in mind support not only for some of the existing institutes, including the four now being supported by the Ford and Rockefeller Foundations [IRRI, CIMMYT, IITA, and CIAT], but also, as occasion permits, for a number of new ones.

In 1969, World Bank President Robert McNamara (who had been US Secretary of Defense under Presidents Kennedy and Johnson) wrote to the heads of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) in Rome and the United Nations Development Fund (UNDP) in New York saying: I am writing to propose that the FAO, the UNDP and the World Bank jointly undertake to organize a long-term program of support for regional agricultural research institutes. I have in mind support not only for some of the existing institutes, including the four now being supported by the Ford and Rockefeller Foundations [IRRI, CIMMYT, IITA, and CIAT], but also, as occasion permits, for a number of new ones.

And that’s how I got into research management in 2001, when IRRI Director General Ron Cantrell invited me to join the senior management team as

And that’s how I got into research management in 2001, when IRRI Director General Ron Cantrell invited me to join the senior management team as

Soccie Almazan became the curator of the wild rices that had to be grown in a quarantine screenhouse some distance from the main research facilities, on the far side of the experiment station. But the one big change that we made was to incorporate all the germplasm types, cultivated or wild, into a single genebank collection, rather than the three collections. Soccie brought about some major changes in how the wild species were handled, and with an expansion of the screenhouses in the early 1990s (as part of the overall refurbishment of institute infrastructure) the genebank at last had the space to adequately grow (in pots) all this valuable germplasm that required special attention. See the video from 4:30. Soccie retired from IRRI in the last couple of years.

Soccie Almazan became the curator of the wild rices that had to be grown in a quarantine screenhouse some distance from the main research facilities, on the far side of the experiment station. But the one big change that we made was to incorporate all the germplasm types, cultivated or wild, into a single genebank collection, rather than the three collections. Soccie brought about some major changes in how the wild species were handled, and with an expansion of the screenhouses in the early 1990s (as part of the overall refurbishment of institute infrastructure) the genebank at last had the space to adequately grow (in pots) all this valuable germplasm that required special attention. See the video from 4:30. Soccie retired from IRRI in the last couple of years.

Until the Crop Trust stepped in to provide the security of long-term funding through its

Until the Crop Trust stepped in to provide the security of long-term funding through its