I opened my email this morning to find one with the sad news that Richard Sawyer, the first Director General of the International Potato Center (CIP) had died at his home in North Carolina on 9 March. He was 93, just a week short of his 94th birthday.

I opened my email this morning to find one with the sad news that Richard Sawyer, the first Director General of the International Potato Center (CIP) had died at his home in North Carolina on 9 March. He was 93, just a week short of his 94th birthday.

Richard was my first boss from January 1973 when I joined the International Potato Center (CIP) as an associate taxonomist in Lima, Perú. In fact, Richard was one of the first Americans I had ever met, and it was quite an eye-opener, as a young British graduate, to be working for an organization led by an American.

I first met Richard in early summer 1971 or thereabouts, while I was a graduate student at the University of Birmingham. My major professor, and head of the Department of Botany at the university was renowned potato taxonomist Jack Hawkes. Jack had made a collecting expedition for wild potatoes to Bolivia in the first couple months of 1971. And his trip was supported by the USAID-funded North Carolina State University – Peru potato project. Richard had been in Lima since 1966 as head of that mission. I believe that Jack stayed in Lima with Richard and his wife, and had the opportunity to discuss with Richard how the recently-founded MSc course on Conservation and Utilization of Plant Genetic Resources could support the genetic resources activities at what would soon become the International Potato Center. Richard wanted to send a young Peruvian scientist (Zosimo Huaman) for training at Birmingham, but wondered if Jack had anyone in mind who could accept a one-year assignment in Peru while Zosimo was away in Birmingham studying for his MSc degree.

During a visit to meet with potential donors for the fledgling CIP in the UK, Richard came up to Birmingham from London to discuss some more about training possibilities, and the one-year assignment. And Jack invited me to meet Richard. I remember quite clearly entering Jack’s office, and my first impression of Richard Sawyer. “Good grief,” I thought to myself, “I’ve come to meet Uncle Sam!” At that time, Richard sported a goatee beard and, to my mind, was the spitting image of ‘Sam’.

I eventually moved to Lima in January 1973, and spent the next eight happy and scientifically fruitful years with CIP in Perú and Central America.

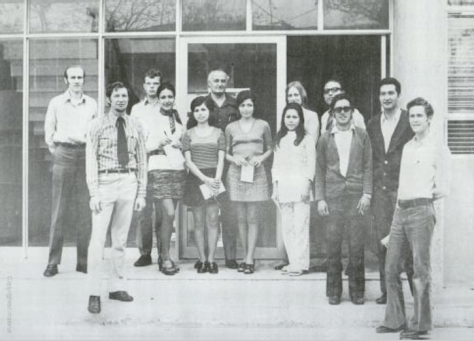

CIP staff in 1972, taken a few months before I joined the center. L to r: Ed French, Richard Sawyer, John Vessey, ??, Rosa Rodriguez, Carlos Bohl, Sr., Haydee de Zelaya, Rosa Mendez, Heather ??, Oscar Gil, Javier Franco, Luis Salazar, David Baumann

A family man. There are several things I remember specially about Richard. When I joined CIP he had recently remarried, and was devoted to his young wife Norma who was expecting their son Ricardo Jr. The Sawyers hosted a cocktail at their San Isidro apartment during that first week I was in Lima for the participants of a potato genetic resources and taxonomy planning workshop. Almost the whole staff of CIP had been invited – we were so few that everyone could easily fit into their apartment.

During that workshop we traveled to Huancayo to see the germplasm collection, and Richard drove one of the vehicles himself. Staying at the Turista hotel in the center of Huancayo, we spent that first night drinking pisco sours and playing dudo for a couple of hours.

Richard practiced what he preached. He was very supportive of CIP scientists and their families, and always encouraged his staff to maintain a healthy balance between work and home. At 4 pm each day he was the first out of the office and on to the frontón court; he was very competitive.

A TPS incident. I remember one (potentially disastrous) incident, in about 1978 or 1979, during the annual review meeting held in Lima, and in which all staff from around the world also participated. I came down to Lima from Costa Rica where I was leading CIP’s Region II Program (Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean). After several presentations about the emerging technology of true potato seed (TPS) during the first couple of days, the then Director of Research, Dr Ory Page from Canada, opened the floor for general comments and questions. I’d been storing up some comments and, nothing venture, nothing gained, stuck my hand up and began to make several critical comments about the TPS program and how it was not currently applicable to the farmers of Central America.

Well, as they say, the ‘proverbial’ hit the fan. Richard was seated immediately in front of me, among the CIP staff. He turned on me, and gave me a public dressing down. I decided not to accept this quietly, and responded as vigorously. As tempers began to fray, the Chair of the CIP Board Program Committee, British scientist Dr Glyn Burton, suspended the meeting. Richard stormed out to his office, followed by Dr Ken Brown, head of Regional Research and my immediate boss who was upset at Richard’s reaction. Several colleagues came up to me during the enforced break, and while they might have concurred with my point of view, felt that I had burned my bridges at CIP, and was likely to lose my job.

Far from it. A couple of days later, Richard came looking for me and apologized for how he’d behaved towards me; he told me that I’d had every right to question aspects of CIP’s research. I think this whole incident strengthened the relationship I had with Richard, and he was very supportive. It also indicated to me that Richard was a supremely confident person, and a strong leader.

Moving on. In 1980, a teaching position opened at the University of Birmingham. I was keen to apply, but felt I had to discuss the various options first. Ken Brown advised me to talk directly with Richard, and it was fortunate that I was already back in Lima, having left Costa Rica in November just before the Birmingham position was announced. Richard strongly encouraged me to apply for the Birmingham lectureship, but at the same time offering me a new five-year contract with CIP should I fail with my application. Now that was, as you can imagine, an unbelievable way to approach a job interview. I was offered the position and resigned from CIP in March 1981 to return to the UK.

But that wasn’t the end of my relationship with CIP. The UK Department for International Development (then the Overseas Development Institute) supported my research project with CIP on TPS of all things during the 1980s. And I also carried out a couple of consultancies for CIP, the more significant being an evaluation of a Swiss-funded seed potato project in Perú, during which I always had the opportunity to meet with Richard. He was always interested in what I was up to and how the family was getting on. After all, my wife Stephanie had also personally been offered a position at CIP by Richard from July 1973.

Richard’s legacy. There are so many things I could point out, but three come most readily to my mind:

- Richard was a compassionate individual, very supportive of his staff and their families. But having a clear vision, he could also be determined and make the tough decisions. This served CIP extremely well during his tenure.

- He placed the conservation of the germplasm collection and its use at the heart of CIP’s strategy and research. Later this was expanded to include sweet potatoes and several ‘minor’ Andean tuber crops. Focusing only on potato for the first decade enabled CIP to establish and maintain a strong research program, that had the strong foundation for expansion into other tuber crops.

- His vision of regional research and collaboration with potato researchers around the world – and the use of CIP funding to support these scientists as part of CIP’s core research program – was not always appreciated around the CGIAR in the early 1970s. It was innovative, and CIP was able to have an early impact on and bring new technologies to potato programs and systems right around the world. The establishment of PRECODEPA in 1978 was one of these important initiatives. Not only did Richard persevere, but he showed that this model of collaboration was one applicable to other centers and their mandate crops. It is the modus operandi today.

It is always sad when a colleague and friend passes away. While we – his family, friends and former colleagues – mourn his passing, let us also celebrate a life of service to international agriculture by this extraordinary individual. It has been my privilege to count Richard Sawyer as a friend and mentor. My life has certainly been profoundly changed by knowing and working with him.

Deepest condolences to his wife Norma, son Ricardo Jr., his daughters from his first marriage, and all his family.

Humble? Boiled, mashed, fried, roast, chipped or prepared in many other ways, the potato is surely the King of Vegetables. And for 20 years in the 1970s and 80s, potatoes were the focus of my own research.

Humble? Boiled, mashed, fried, roast, chipped or prepared in many other ways, the potato is surely the King of Vegetables. And for 20 years in the 1970s and 80s, potatoes were the focus of my own research.

![Jörg Hempel [CC BY-SA 3.0 de (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/deed.en)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://mikejackson1948.blog/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/dryas_octopetala_lc0327.jpg?w=200&h=267)

![By Sami Keinänen (www.flickr.com) [CC BY-SA 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://mikejackson1948.blog/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/guinness.jpg?w=97&h=150) But all work and no play makes Jack(son) a dull boy. We had plenty of opportunity of letting our hair down. Every day when we returned from the field we were pleased to see a line of pints of Guinness that had already been poured in readiness for our arrival, around 5 pm. In the evening – besides enjoying a few more glasses of Guinness – we enjoyed dancing to a resident fiddler, Joseph Glynn, and a young barmaid who played the tin whistle. Since I had spent the previous year learning folk dancing, I organized several impromptu ceilidhs.

But all work and no play makes Jack(son) a dull boy. We had plenty of opportunity of letting our hair down. Every day when we returned from the field we were pleased to see a line of pints of Guinness that had already been poured in readiness for our arrival, around 5 pm. In the evening – besides enjoying a few more glasses of Guinness – we enjoyed dancing to a resident fiddler, Joseph Glynn, and a young barmaid who played the tin whistle. Since I had spent the previous year learning folk dancing, I organized several impromptu ceilidhs.

Sponsored by the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), the 4th International Rice Congress brought together rice researchers from all over the world. Previous congresses had been held in Japan, India and last time, in 2010, in Hanoi, Vietnam (for which I also organized the science conference). This fourth congress, known as IRC2014 for short, had three main components:

Sponsored by the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), the 4th International Rice Congress brought together rice researchers from all over the world. Previous congresses had been held in Japan, India and last time, in 2010, in Hanoi, Vietnam (for which I also organized the science conference). This fourth congress, known as IRC2014 for short, had three main components:

Way back at the beginning of 2013 IRRI management asked me if I would like to organize the science conference in Bangkok, having taken on that role in 2009 before I retired from IRRI and for six months after I left. From May 2013 until IRC2014 was underway, I made four trips to the Far East, twice to Bangkok and three times to IRRI. We formed a

Way back at the beginning of 2013 IRRI management asked me if I would like to organize the science conference in Bangkok, having taken on that role in 2009 before I retired from IRRI and for six months after I left. From May 2013 until IRC2014 was underway, I made four trips to the Far East, twice to Bangkok and three times to IRRI. We formed a

What does 2015 hold in store?

What does 2015 hold in store?

In 1976, the USA celebrated its bicentennial. Jimmy Carter was elected the 39th President in November that year and took office on 20 January 1977. During his first overseas trip as president, Carter visited the UK, and on Friday 6 May he made a special visit to Washington Old Hall, flying into Newcastle International Airport (known as Woolsington Airport then) on Air Force One (a Boeing 707), in the company of UK Prime Minister Jim Callaghan. Click

In 1976, the USA celebrated its bicentennial. Jimmy Carter was elected the 39th President in November that year and took office on 20 January 1977. During his first overseas trip as president, Carter visited the UK, and on Friday 6 May he made a special visit to Washington Old Hall, flying into Newcastle International Airport (known as Woolsington Airport then) on Air Force One (a Boeing 707), in the company of UK Prime Minister Jim Callaghan. Click

Clickety click? You play bingo, don’t you? It’s the 66 ball.

Clickety click? You play bingo, don’t you? It’s the 66 ball.

While I knew that Lynne spent most of his time producing hit albums for other musicians, and writing new material, I hadn’t realized how unpopular ELO had become since their heyday in the 70s. Apparently

While I knew that Lynne spent most of his time producing hit albums for other musicians, and writing new material, I hadn’t realized how unpopular ELO had become since their heyday in the 70s. Apparently