A perspective from 25 years ago

In April 1989, Brian Ford-Lloyd, Martin Parry and I organized a workshop on plant genetic resources and climate change at the University of Birmingham. A year later, Climatic Change and Plant Genetic Resources was published (by Belhaven Press), with eleven chapters summarizing perspectives on climatic change and how it might affect plant populations, and its expected impact on agriculture around the world.

We asked whether genetic resources could cope with climate change, and would plant breeders be able to access and utilize genetic resources as building blocks of new and better-adapted crops? We listed ten consensus conclusions from the workshop:

- The importance of developing collection, conservation and utilization strategies for genetic resources in the light of climatic uncertainty should be recognised.

- There should be marked improvement in the accuracy of climate change predictions.

- There must be concern about sea level rises and their impact on coastal ecosystems and agriculture.

- Ecosystems should be preserved thereby allowing plant species – especially crop species and their wild relatives – the flexibility to respond to climate change.

- Research should be prioritized on tropical dry areas as these might be expected to be more severely affected by climate change.

- There should be a continuing need to characterize and evaluate germplasm that will provide adaptation to changed climates.

- There should be an increase in screening germplasm for drought, raised temperatures, and salinity.

- Research on the physiology underlying C3 and C4 photosynthesis should merit further investigation with the aim of increasing the adaptation of C3 crops.

- Better simulation models should drive a better understanding of plant responses to climate change.

- Plant breeders should become more aware of the environmental impacts of climate change, so that breeding programs could be modified to accommodate these predicted changes.

Climate change perspectives today

There is much less scepticism today about greenhouse gas-induced climate change and what its consequences might be, even though the full impacts of climate change cannot yet be predicted with certainty. On the other hand, the nature of weather variability – particularly in the northern hemisphere in recent years – has left some again questioning whether our climate really is warming. But the evidence is there for all to see, even as the sceptics refuse to accept the empirical data of increases in atmospheric CO2, for example, or the unprecedented summer melting of sea ice in the Arctic and the retreat of glaciers in the Alps.

Over the past decade the world has experienced a number of severe climate events – wake-up calls to what might be the normal pattern in the future under a changed climate – such as extreme drought in one region, or unprecedented flooding in another. Even the ‘normal’ weather patterns of Western Europe appear to have become disrupted in recent years leading to increased stresses on agriculture.

Some of the same questions we asked in 1989 are still relevant. However, there are some very important differences today from the situation then. Our understanding of what is happening to the climate has been refined significantly over the past two decades, as the efforts of the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) have brought climate scientists worldwide together to provide better predictions of how climate will change. Furthermore, governments are now taking the threat of climate change seriously, and international agreements like the Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework on Climate Change, which came into force in 2005 and, even with their limitations, have provided the basis for society and governments to take action to mitigate the effects of climate change.

A new book from CABI

It is in this context, therefore, that our new book Plant Genetic Resources and Climate Change was commissioned to bring together, in a single volume, some of the latest perspectives about how genetic resources can contribute to achieving food security under the challenge of a changing climate. We also wanted to highlight some key issues for plant genetic resources management, to demonstrate how perspectives have changed over two decades, and discuss some of the actual responses and developments.

It is in this context, therefore, that our new book Plant Genetic Resources and Climate Change was commissioned to bring together, in a single volume, some of the latest perspectives about how genetic resources can contribute to achieving food security under the challenge of a changing climate. We also wanted to highlight some key issues for plant genetic resources management, to demonstrate how perspectives have changed over two decades, and discuss some of the actual responses and developments.

Food security and genetic resources

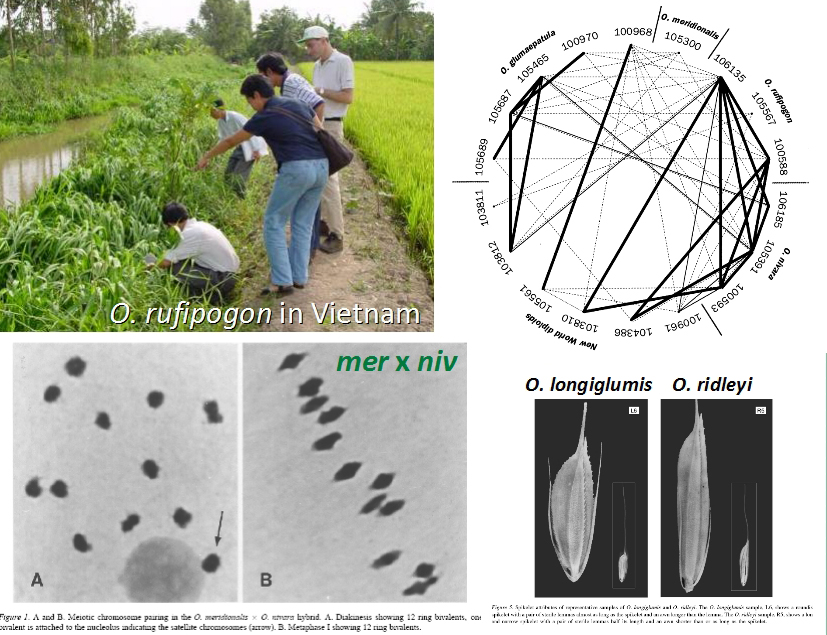

So what has happened during the past two decades or so? In 1990, world population was under 6 billion, but today there are more than 1 billion additional mouths to feed. The World Food Program estimates that there are 870 million people in the world who do not get enough food to lead a normal and active life. Food insecurity remains a major concern. In an opening chapter, Robert Zeigler (IRRI) provides an overview on food security today, how problems of food production will be exacerbated by climate change, and how – in the case of one crop, rice – access to and use of genetic resources have already begun to address many of the challenges that climate change will bring.

Expanding on the plant genetic resources theme, Brian Ford-Lloyd (University of Birmingham) and his co-authors provide (in Chapter 2) a broad overview of important issues concerning their conservation and use, including conservation approaches, strategies, and responses that become more relevant under the threat of climate change.

Climate projections

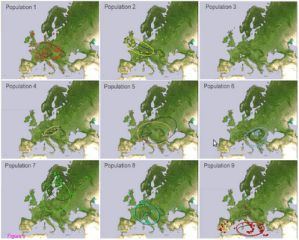

In three chapters, Richard Betts (UK Met Office) and Ed Hawkins (University of Reading), Martin Parry (Imperial College – London), and Pam Berry (Oxford University) and her co-authors describe scenarios for future projected climates (Chapter 3), the effects of climate change on food production and the risk of hunger (Chapter 4), and regional impacts of climate change on agriculture (Chapter 5), respectively. Over the past two decades, development of the global circulation models now permits climate change prediction with greater certainty. And combining these with physiological modelling and geographical information systems (GIS) we now have a better opportunity to assess what the impacts of climate change might be on agriculture, and where.

Sharing genetic resources

In the 1990s, we became more aware of the importance of biodiversity in general, and several international legal instruments such as the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture were agreed among nations to govern access to and use of genetic resources for the benefit of society. A detailed discussion of these developments is provided by Gerald Moore (formerly FAO) and Geoffrey Hawtin (formerly IPGRI) in Chapter 6.

Crop wild relatives, in situ and on-farm conservation

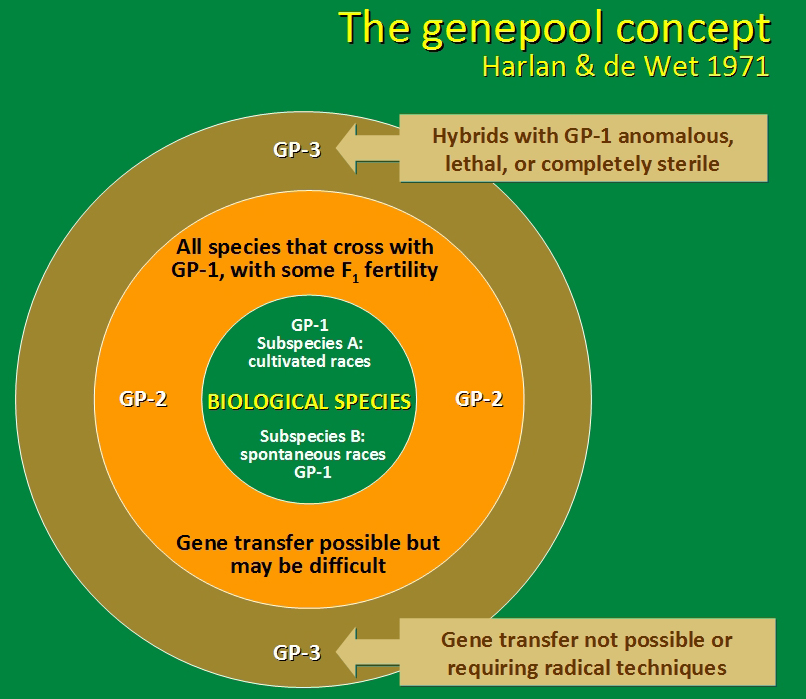

In Chapters 7 and 8, we explore the in situ conservation of crop genetic resources and their wild relatives. Nigel Maxted and his co-authors (University of Birmingham) provide an analysis of the importance of crop wild relatives in plant breeding and the need for their comprehensive conservation. Mauricio Bellon and Jacob van Etten (Bioversity International) discuss the challenges for on-farm conservation in centres of crop diversity under climate change.

Informatics and the impact of molecular biology

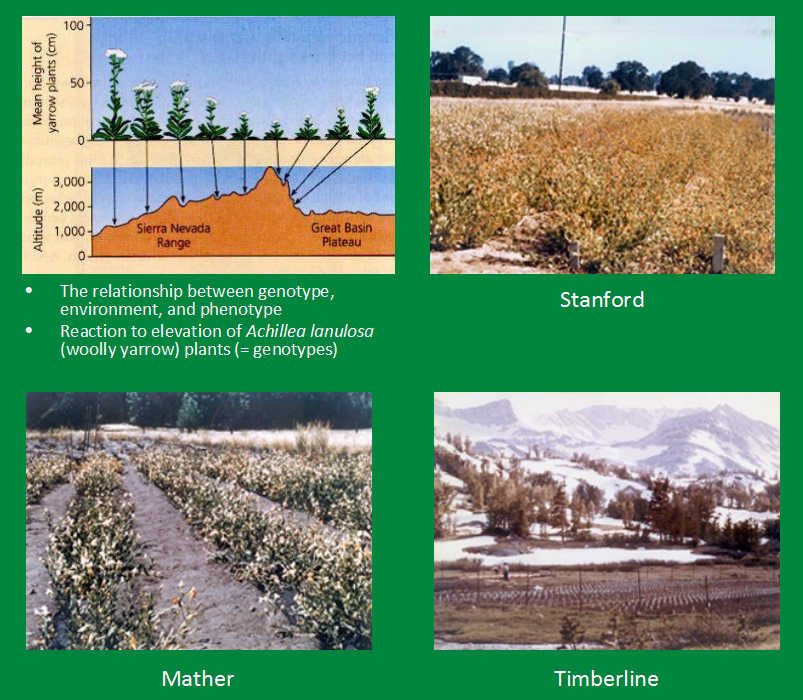

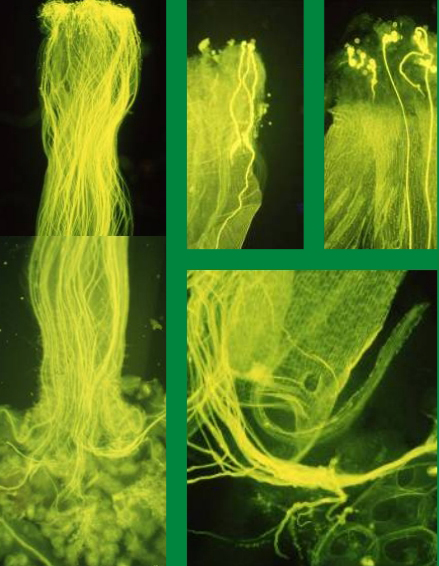

Discussing the data management aspects of germplasm collections, Helen Ougham and Ian Thomas (Aberystwyth University) describe in Chapter 9 several developments in genetic resources databases, and regional projects aimed at facilitating conservation and use. Two decades ago we had little idea of what would be the impact of molecular biology and its associated data today on the identification of useful crop diversity and its use in plant breeding. In Chapter 10, Kenneth McNally (IRRI) provides a comprehensive review of the present and future of how genomics and other molecular technologies – and associated informatics – are revolutionizing how we study and understand diversity in plant species. He also provides many examples of how responses to environmental stresses that can be expected as a result of climate change can be detected at the molecular level, opening up unforeseen opportunities for precise germplasm evaluation, identification, and use. Susan Armstrong (University of Birmingham, Chapter 11) describes how a deeper understanding of sexual reproduction in plants, specifically the processes of meiosis, should lead to better use of germplasm in crop breeding as a response to climate change.

Coping with climate change

In a final series of five chapters, responses to a range of abiotic and biotic stresses are documented: heat (by Maduraimuthu Djanaguiraman and Vara Prasad, Kansas State University, Chapter 12); drought (Salvatore Ceccarelli, formerly ICARDA, Chapter 13); salinity (including new domestications) by William Erskine, University of Western Australia, and his co-authors in Chapter 14; submergence tolerance in rice as a response to flooding (Abdelbagi Ismail, IRRI and David Mackill, University of California – Davis, Chapter 15); and finally plant-insect interactions and prospects for resistance breeding using genetic resources (by Jeremy Pritchard, University of Birmingham, and co-authors, Chapter 16).

Why this book is timely and important

The climate change that has been predicted is an enormous challenge for society worldwide. Nevertheless, progress in the development of scenarios of climate change – especially the development of more reliable projections of changes in precipitation – now provide a much more sound basis for using genetic resources in plant breeding for future climates. While important uncertainty remains about changes to variability of climate, especially to the frequency of extreme weather events, enough is now known about the range of possible changes (for example by using current analogues of future climate) to provide a basis for choosing genetic resources in breeding better-adapted crops. Even the challenge of turbo-charging the photosynthesis of a C3 crop like rice has already been taken up by a consortium of scientists worldwide under the leadership of the International Rice Research Institute in the Philippines.

Unlike the situation in 1989, estimates of average sea level rise, and consequent risks to low lying land areas, are now characterised by less uncertainty and indicate the location and scale of the challenges posed by inundation, by soil waterlogging and by land salinization. Responses to all of these challenges and the progress achieved are spelt out in detail in several chapters in this volume.

We remain confident that research will continue to demonstrate just what is needed to mitigate the worst effects of climate change; that germplasm access and use frameworks – despite their flaws – facilitate breeders to choose and use genetic resources; and that ultimately, genetic resources will be used successfully in crop breeding for climate change thereby enhancing food security.

Would you like to buy a copy?

The authors will receive their page proofs any day now, and we should have the final edits made by the middle of September. CABI expects to publish Plant Genetic Resources and Climate Change in December 2013. Already this book can be found online through a Google search even though it’s not yet published. But do go to the CABI Bookshop – the book has been priced at £85 (or USD160 and €110). If you order online I’m told there is a discount on the list price.

_______________________________________________________

* This post is based on the Preface from the forthcoming CABI book.

My flight from Manila arrived quite late at night, and a vehicle and driver were sent to KL airport to pick me up. On the journey from the airport my driver became quite chatty. He asked where I was from, and when I told him I was working in the Philippines on rice, he replied ‘You must be working at IRRI, then‘ (

My flight from Manila arrived quite late at night, and a vehicle and driver were sent to KL airport to pick me up. On the journey from the airport my driver became quite chatty. He asked where I was from, and when I told him I was working in the Philippines on rice, he replied ‘You must be working at IRRI, then‘ (

I was visiting in connection with the

I was visiting in connection with the

Grown only in the UK, the Bramley is a ‘cooking apple’ that makes the best pies. It produces large, green fruits (in this photo the apples are about 4 inches, 10 cm in diameter, but they can come much larger) that are just too tart to eat raw – well, for me at least. I’m not really sure if there’s a tradition of using special cooking varieties elsewhere, but in many of the countries I’ve visited, dessert apples are used in apple pies, which are somewhat too sweet for my palate.

Grown only in the UK, the Bramley is a ‘cooking apple’ that makes the best pies. It produces large, green fruits (in this photo the apples are about 4 inches, 10 cm in diameter, but they can come much larger) that are just too tart to eat raw – well, for me at least. I’m not really sure if there’s a tradition of using special cooking varieties elsewhere, but in many of the countries I’ve visited, dessert apples are used in apple pies, which are somewhat too sweet for my palate.

Apples were taken to North America in colonial times. Do you know the story of

Apples were taken to North America in colonial times. Do you know the story of

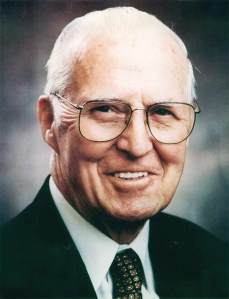

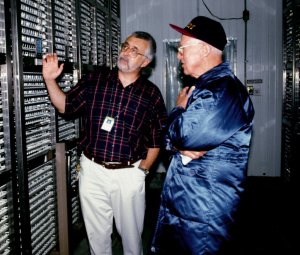

My predecessor at IRRI was Dr Te-Tzu Chang, known to everyone as ‘TT’. He joined IRRI in 1962 and over the years had built the germplasm collection to about 75,000 or so accessions by the time I joined the institute, as well as leading IRRI’s upland rice breeding efforts.

My predecessor at IRRI was Dr Te-Tzu Chang, known to everyone as ‘TT’. He joined IRRI in 1962 and over the years had built the germplasm collection to about 75,000 or so accessions by the time I joined the institute, as well as leading IRRI’s upland rice breeding efforts.

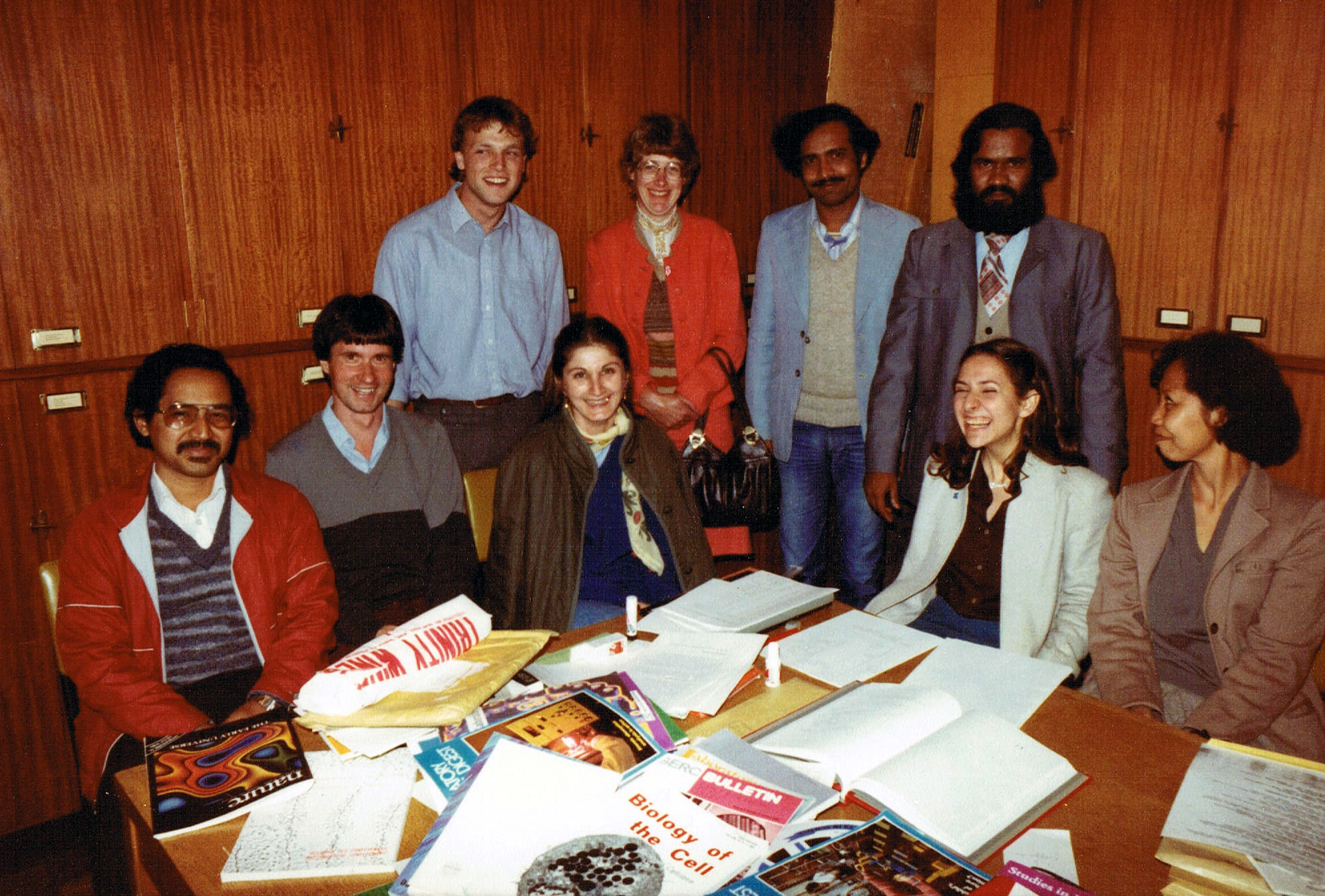

In 1989, my former colleagues at the University of Birmingham, Brian Ford-Lloyd and Martin Parry, and I organized a two-day symposium on genetic resources and climate change. The papers presented were published in Climatic Change and Plant Genetic Resources by Belhaven Press (ISBN 1 85293 102 7), edited by me and the other two.

In 1989, my former colleagues at the University of Birmingham, Brian Ford-Lloyd and Martin Parry, and I organized a two-day symposium on genetic resources and climate change. The papers presented were published in Climatic Change and Plant Genetic Resources by Belhaven Press (ISBN 1 85293 102 7), edited by me and the other two. In a particularly prescient chapter, the late Professor Harold Woolhouse discussed how photosynthetic biochemistry is relevant to adaptation to climate change. Two decades later the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) based in the Philippines is leading a worldwide effort to turbocharge the photosynthesis of rice, by converting the plant from so-called C3 to C4 photosynthesis.

In a particularly prescient chapter, the late Professor Harold Woolhouse discussed how photosynthetic biochemistry is relevant to adaptation to climate change. Two decades later the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) based in the Philippines is leading a worldwide effort to turbocharge the photosynthesis of rice, by converting the plant from so-called C3 to C4 photosynthesis.

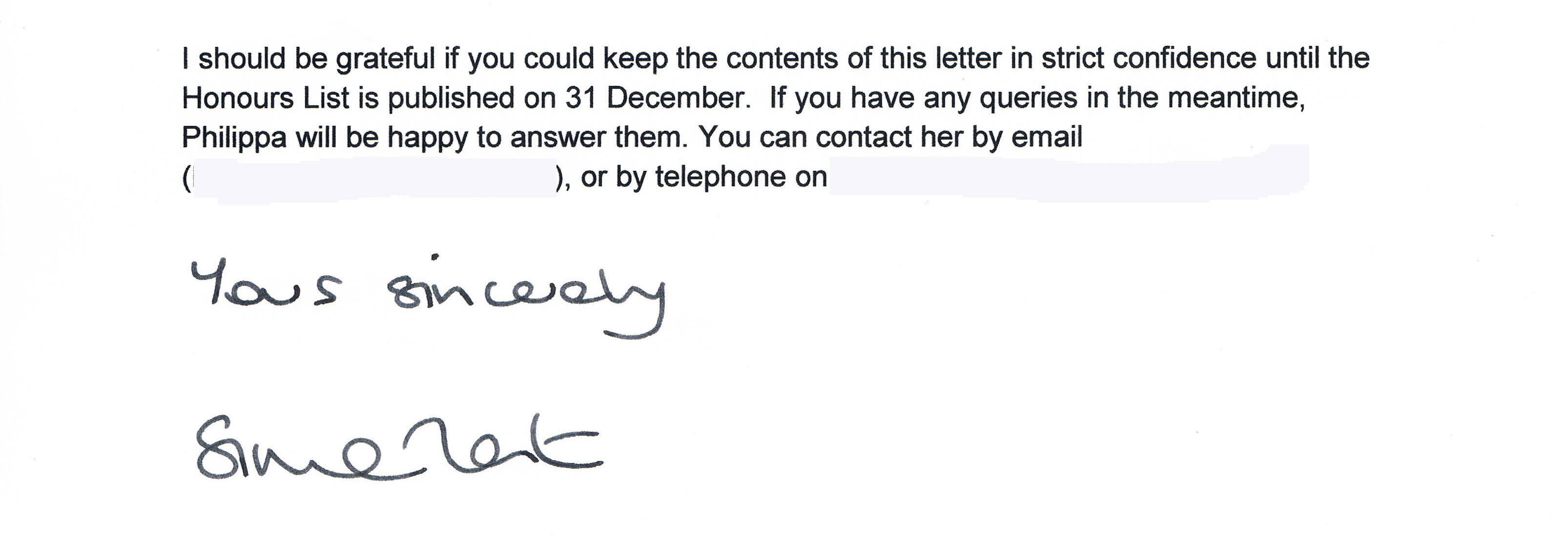

Michael Jackson is the Managing Editor for this book. He retired from the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in 2010. For 10 years he was Head of the Genetic Resources Center, managing the International Rice Genebank, one of the world’s largest and most important genebanks. For nine years he was Director for Program Planning and Communications. He was Adjunct Professor of Agronomy at the University of the Philippines-Los Baños. During the 1980s he was Lecturer in the School of Biological Sciences at the University of Birmingham, focusing on the conservation and use of plant genetic resources. From 1973-81 he worked at the International Potato Center, in Lima, Perú and in Costa Rica. He now works part-time as an independent agricultural research and planning consultant. He was appointed OBE in The Queen’s New Year’s Honours 2012, for services to international food science.

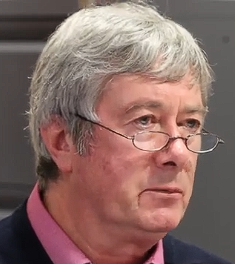

Michael Jackson is the Managing Editor for this book. He retired from the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in 2010. For 10 years he was Head of the Genetic Resources Center, managing the International Rice Genebank, one of the world’s largest and most important genebanks. For nine years he was Director for Program Planning and Communications. He was Adjunct Professor of Agronomy at the University of the Philippines-Los Baños. During the 1980s he was Lecturer in the School of Biological Sciences at the University of Birmingham, focusing on the conservation and use of plant genetic resources. From 1973-81 he worked at the International Potato Center, in Lima, Perú and in Costa Rica. He now works part-time as an independent agricultural research and planning consultant. He was appointed OBE in The Queen’s New Year’s Honours 2012, for services to international food science. Brian Ford-Lloyd is Professor of Conservation Genetics at the University of Birmingham, Director of the University Graduate School, and Deputy Head of the School of Biosciences. As Director of the University Graduate School he aims to ensure that doctoral researchers throughout the University are provided with the opportunity, training and facilities to undertake internationally valued research that will lead into excellent careers in the UK and overseas. He draws from his experience of having successfully supervised over 40 doctoral researchers from the UK and many other parts of the world in his chosen research area which includes the study of the natural genetic variation in plant populations, and agricultural plant genetic resources and their conservation.

Brian Ford-Lloyd is Professor of Conservation Genetics at the University of Birmingham, Director of the University Graduate School, and Deputy Head of the School of Biosciences. As Director of the University Graduate School he aims to ensure that doctoral researchers throughout the University are provided with the opportunity, training and facilities to undertake internationally valued research that will lead into excellent careers in the UK and overseas. He draws from his experience of having successfully supervised over 40 doctoral researchers from the UK and many other parts of the world in his chosen research area which includes the study of the natural genetic variation in plant populations, and agricultural plant genetic resources and their conservation. Martin Parry

Martin Parry

When the late

When the late

Here is the list of University of Birmingham PhD students who worked on potatoes, as far as I can remember. All of them from 1975 (with the exception of Ian Gubb) had also attended the MSc course on genetic resources:

Here is the list of University of Birmingham PhD students who worked on potatoes, as far as I can remember. All of them from 1975 (with the exception of Ian Gubb) had also attended the MSc course on genetic resources: Richard Lester (UK), 1962. Taught at Makerere University in Uganda, before joining the Dept. of Botany at Birmingham in 1969. Retired in 2002, and died in 2006. Studied the biochemical systematics of Mexican wild Solanum species. The species Solanum lesteri is named after him.

Richard Lester (UK), 1962. Taught at Makerere University in Uganda, before joining the Dept. of Botany at Birmingham in 1969. Retired in 2002, and died in 2006. Studied the biochemical systematics of Mexican wild Solanum species. The species Solanum lesteri is named after him.

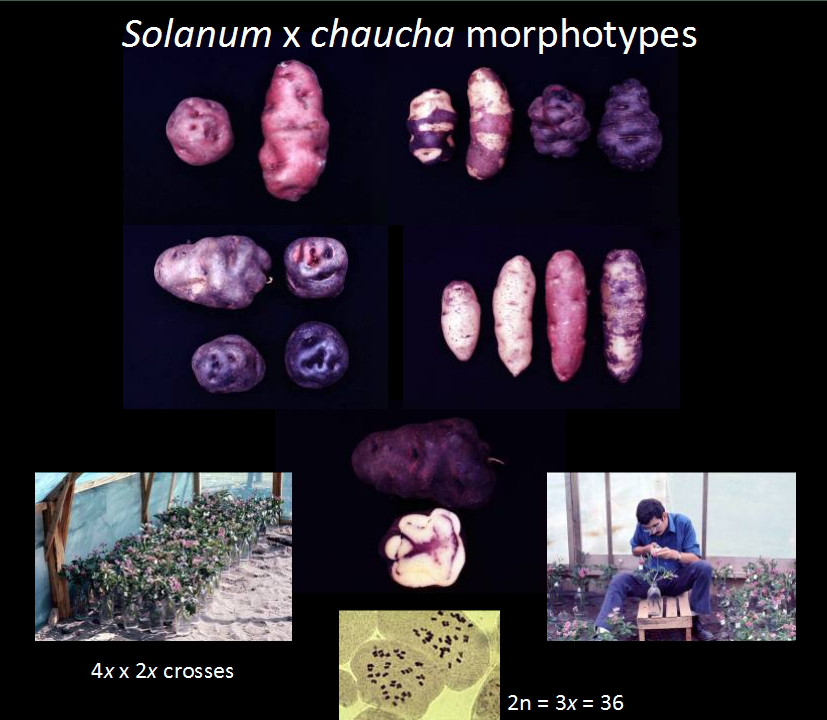

Katsuo Armando Okada (Argentina), 1970 (?). Retired. Was with IBPGR for a while in the 1980s (?) in Colombia. Studied the origin of Solanum x rechei from Argentina.

Katsuo Armando Okada (Argentina), 1970 (?). Retired. Was with IBPGR for a while in the 1980s (?) in Colombia. Studied the origin of Solanum x rechei from Argentina.

David Astley (UK), 1975. Became the curator of the vegetable genebank at Wellesbourne (now the

David Astley (UK), 1975. Became the curator of the vegetable genebank at Wellesbourne (now the

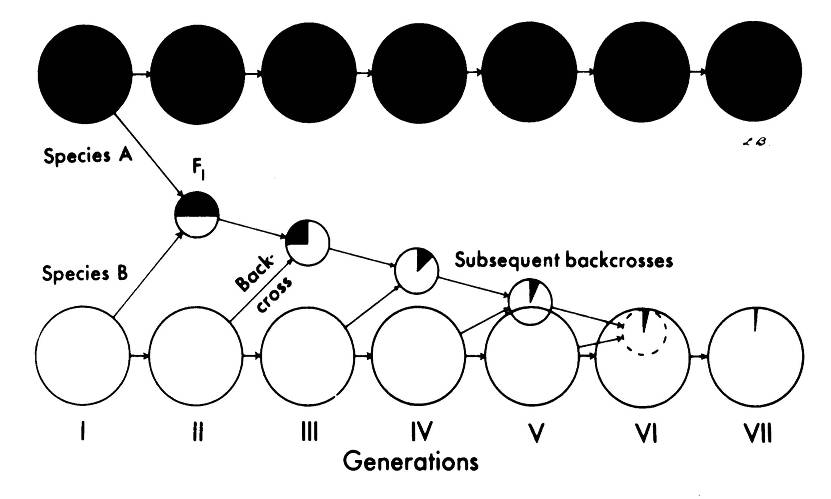

Peter Schmiediche (Germany), 1977. He continued working with CIP as a potato breeder (for resistance to bacterial wilt), and was later CIP’s regional leader based in Indonesia. Now retired and sharing his time between Texas (where his children settled) and his native Berlin. Studied the bitter potatoes Solanum x juzepczukii (3x) and S. x curtilobum (5x). Joint with CIP and Roger Rowe.

Peter Schmiediche (Germany), 1977. He continued working with CIP as a potato breeder (for resistance to bacterial wilt), and was later CIP’s regional leader based in Indonesia. Now retired and sharing his time between Texas (where his children settled) and his native Berlin. Studied the bitter potatoes Solanum x juzepczukii (3x) and S. x curtilobum (5x). Joint with CIP and Roger Rowe. Carlos Arbizu (Peru), 1990. An expert on minor Andean tuber crops, he came from the University of Ayacucho. Spent time working in the germplasm program at CIP. Studied the origin and value of resistance to spindle tuber viroid in Solanum acaule. Joint with CIP and principal virologist Luis Salazar (who gained his PhD while studying at the

Carlos Arbizu (Peru), 1990. An expert on minor Andean tuber crops, he came from the University of Ayacucho. Spent time working in the germplasm program at CIP. Studied the origin and value of resistance to spindle tuber viroid in Solanum acaule. Joint with CIP and principal virologist Luis Salazar (who gained his PhD while studying at the  Susan Juned (UK), 1994. Now a sustainable technology consultant, Sue is an active local government councillor, and has stood for election to parliament on a couple of occasions for the Liberal Democrats. Studied

Susan Juned (UK), 1994. Now a sustainable technology consultant, Sue is an active local government councillor, and has stood for election to parliament on a couple of occasions for the Liberal Democrats. Studied  David Tay (Malaysia), 2000. He worked in Australia and then was Director of the USDA Ornamental Plant Germplasm Center in Columbus, Ohio, but returned to CIP as head of the genetic resources unit in 2007. He’s now left CIP. I think he worked on diploid cultivated species. Joint with CIP. Not sure why his PhD is dated 2000, as he’d been in CIP in the late 70s.

David Tay (Malaysia), 2000. He worked in Australia and then was Director of the USDA Ornamental Plant Germplasm Center in Columbus, Ohio, but returned to CIP as head of the genetic resources unit in 2007. He’s now left CIP. I think he worked on diploid cultivated species. Joint with CIP. Not sure why his PhD is dated 2000, as he’d been in CIP in the late 70s.

Roger Rowe, who had been in charge of the

Roger Rowe, who had been in charge of the  Ms. Genoveva ‘Eves’ Loresto passed away in Cebu on 5 April after a long battle with cancer.

Ms. Genoveva ‘Eves’ Loresto passed away in Cebu on 5 April after a long battle with cancer.

A rather interesting experiment was reported on the

A rather interesting experiment was reported on the

The

The

Brian Ford-Lloyd (right, now Professor of Conservation Genetics and Director of the university Graduate School) joined the department in 1979 and was the course tutor for many years, and contributing lectures in data management, among others.

Brian Ford-Lloyd (right, now Professor of Conservation Genetics and Director of the university Graduate School) joined the department in 1979 and was the course tutor for many years, and contributing lectures in data management, among others.

After I resigned from the university to join IRRI in 1991, Dr Nigel Maxted (right) was appointed as a lecturer, and has continued his work on wild relatives of crop plants and in situ conservation. He has also taken students on field courses to the Mediterranean several times.

After I resigned from the university to join IRRI in 1991, Dr Nigel Maxted (right) was appointed as a lecturer, and has continued his work on wild relatives of crop plants and in situ conservation. He has also taken students on field courses to the Mediterranean several times.

And germplasm collecting was repeated in Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam in Asia, and countries in East and southern Africa including Uganda and Madagascar, as well as Costa Rica in Central America (for wild rices). We invested a lot of efforts to train local scientists in germplasm collecting methods. Long-time IRRI employee (now retired) and genetic resources specialist, Eves Loresto (right), visited Bhutan on several occasions.

And germplasm collecting was repeated in Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam in Asia, and countries in East and southern Africa including Uganda and Madagascar, as well as Costa Rica in Central America (for wild rices). We invested a lot of efforts to train local scientists in germplasm collecting methods. Long-time IRRI employee (now retired) and genetic resources specialist, Eves Loresto (right), visited Bhutan on several occasions.

The genebank now has three storage vaults (one was added in the last couple of years) for medium-term (Active) and long-term (Base) conservation. Rice varieties are grown on the IRRI farm, and carefully dried before storage. Seed viability and health is always checked, and resident seed physiologist, Fiona Hay (right, formerly at the

The genebank now has three storage vaults (one was added in the last couple of years) for medium-term (Active) and long-term (Base) conservation. Rice varieties are grown on the IRRI farm, and carefully dried before storage. Seed viability and health is always checked, and resident seed physiologist, Fiona Hay (right, formerly at the

In early 1974 I travelled to southern Peru with a taxonomist friend from the University of St Andrews, Dr Peter Gibbs (right).

In early 1974 I travelled to southern Peru with a taxonomist friend from the University of St Andrews, Dr Peter Gibbs (right).

The drive south in a small Land Rover – down the coastal desert Panamericana highway, across the Nasca plain, climbing to Arequipa, and even higher to Puno – took three days. After resting up in Puno (next to Lake Titicaca), and getting used to the 3827 m altitude, we set off for Cuyo Cuyo. Dropping down from the altiplano at well over 4000 m, Cuyo Cuyo lies at an altitude of about 3300 m. Below the village the valley drops quickly towards the ceja de la montaña – literally ‘eyebrow of the mountain’ – where the humid air of the rainforests below rises up east-facing valleys to form cloud forest.

The drive south in a small Land Rover – down the coastal desert Panamericana highway, across the Nasca plain, climbing to Arequipa, and even higher to Puno – took three days. After resting up in Puno (next to Lake Titicaca), and getting used to the 3827 m altitude, we set off for Cuyo Cuyo. Dropping down from the altiplano at well over 4000 m, Cuyo Cuyo lies at an altitude of about 3300 m. Below the village the valley drops quickly towards the ceja de la montaña – literally ‘eyebrow of the mountain’ – where the humid air of the rainforests below rises up east-facing valleys to form cloud forest.

Peter and I set up camp, so-to-speak, in the local post office where we could sleep, brew the odd cup of tea (there was a small café in the village where we could eat), and gather our specimens together, including a rudimentary drier for the extensive set of oca herbarium samples that Peter intended to make. But more of that particular story later.

Peter and I set up camp, so-to-speak, in the local post office where we could sleep, brew the odd cup of tea (there was a small café in the village where we could eat), and gather our specimens together, including a rudimentary drier for the extensive set of oca herbarium samples that Peter intended to make. But more of that particular story later. The sides of the Cuyo Cuyo valley are covered with the most wonderful system of agricultural terraces, called andenes, which must have been constructed centuries ago, in Inca times, and have been cultivated ever since. Farmers have different terraces dotted around the valley, and when I was there, at least, farmers were still using a communal rotation system. Thus in one part of the valley the terraces were covered in potatoes (year 1 after a fallow), and oca (years 2 and 3), barley or beans (year 4), or fallow (years 5-8) elsewhere. Sheep are corralled on a terrace prior to planting potatoes, and their urine and dung used as fertilizer. Whether, almost 40 years later, this remains the case I do not know.

The sides of the Cuyo Cuyo valley are covered with the most wonderful system of agricultural terraces, called andenes, which must have been constructed centuries ago, in Inca times, and have been cultivated ever since. Farmers have different terraces dotted around the valley, and when I was there, at least, farmers were still using a communal rotation system. Thus in one part of the valley the terraces were covered in potatoes (year 1 after a fallow), and oca (years 2 and 3), barley or beans (year 4), or fallow (years 5-8) elsewhere. Sheep are corralled on a terrace prior to planting potatoes, and their urine and dung used as fertilizer. Whether, almost 40 years later, this remains the case I do not know.

In the 1960s the world faced a huge challenge: how to feed an ever-increasing population, especially in the poorer, developing countries with large agriculture-based societies.

In the 1960s the world faced a huge challenge: how to feed an ever-increasing population, especially in the poorer, developing countries with large agriculture-based societies.

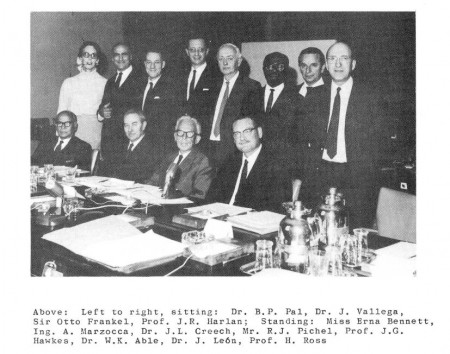

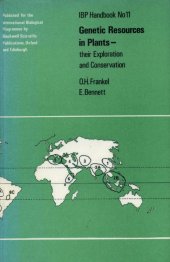

In preparation for Birmingham, I’d been advised to purchase and absorb a book that was published earlier that year, edited by Sir Otto Frankel and Erna Bennett [1] on genetic resources, and dedicated to NI Vavilov. And I came across Vavilov’s name for the first time in the first line of the Preface written by Frankel, and in the first chapter on Genetic resources by Frankel and Bennett. I should state that this was at the beginning of the genetic resources movement, a term coined by Frankel and Bennett at the end of the 60s when they had mobilized efforts to collect and conserve the wealth of diversity of crop varieties (and their wild relatives) – often referred to as landraces – grown all around the world, but were in danger of being lost as newly-bred varieties were adopted by farmers. The so-called Green Revolution had begun to accelerate the replacement of the landrace varieties, particularly among cereals like wheat and rice.

In preparation for Birmingham, I’d been advised to purchase and absorb a book that was published earlier that year, edited by Sir Otto Frankel and Erna Bennett [1] on genetic resources, and dedicated to NI Vavilov. And I came across Vavilov’s name for the first time in the first line of the Preface written by Frankel, and in the first chapter on Genetic resources by Frankel and Bennett. I should state that this was at the beginning of the genetic resources movement, a term coined by Frankel and Bennett at the end of the 60s when they had mobilized efforts to collect and conserve the wealth of diversity of crop varieties (and their wild relatives) – often referred to as landraces – grown all around the world, but were in danger of being lost as newly-bred varieties were adopted by farmers. The so-called Green Revolution had begun to accelerate the replacement of the landrace varieties, particularly among cereals like wheat and rice. Vavilov died of starvation in prison at the relatively young age of 55, following persecution under Stalin through the shenanigans of the charlatan Trofim Lysenko. Lysenko’s legacy also included the rejection of Mendelian genetics in the Soviet Union for many years. Eventually Vavilov was rehabilitated, long after his death, and he was commemorated on postage stamps at the time of his centennial.

Vavilov died of starvation in prison at the relatively young age of 55, following persecution under Stalin through the shenanigans of the charlatan Trofim Lysenko. Lysenko’s legacy also included the rejection of Mendelian genetics in the Soviet Union for many years. Eventually Vavilov was rehabilitated, long after his death, and he was commemorated on postage stamps at the time of his centennial. First,

First,

On a bright, sunny day last November (my birthday, actually) I was outside cleaning the car, when the postman passed by. He handed me several envelopes and my immediate reaction was that this was another load of the usual junk mail. So you can imagine my surprise when I came across one that seemed rather official looking. And I was even more surprised when I read what it had to say – that I had been nominated to become an Officer of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, or OBE, for services to international food science. Well, I was gob-smacked, quite emotional really. I rushed inside to tell Steph – who was equally stunned, and we set to ponder how on earth this had come about. I did some Google detective work, and was able to find out a little more about the

On a bright, sunny day last November (my birthday, actually) I was outside cleaning the car, when the postman passed by. He handed me several envelopes and my immediate reaction was that this was another load of the usual junk mail. So you can imagine my surprise when I came across one that seemed rather official looking. And I was even more surprised when I read what it had to say – that I had been nominated to become an Officer of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, or OBE, for services to international food science. Well, I was gob-smacked, quite emotional really. I rushed inside to tell Steph – who was equally stunned, and we set to ponder how on earth this had come about. I did some Google detective work, and was able to find out a little more about the