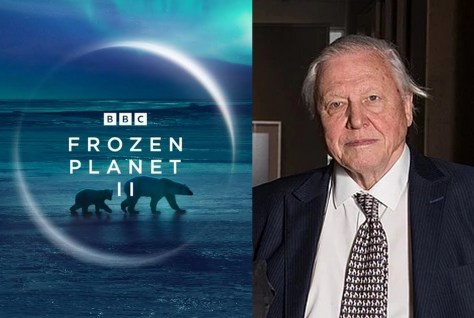

Tomorrow, 22 October, BBC1 will air Sir David Attenborough‘s next blockbuster 8-part series, Planet Earth III¹, just a year after his last series Frozen Planet II was broadcast.

Planet Earth III? From what I have seen in the trailer for the series, perhaps this should—once again—be titled [Animal] Planet Earth III.

There’s no doubt that the filming is spectacular, the ‘stories’ riveting. As one of the cinematographers has written, [the series] is set to be the most ambitious natural history landmark series ever undertaken by the BBC. It will take audiences to stunning new landscapes, showcase jaw-dropping newly-discovered behaviors, and follow the intense struggles of some of our planet’s most amazing animals (my underlining emphasis).

It’s not very likely that the series will feature plants much, if at all. Are plants being short-changed yet again? Of course there are many programs on television about gardening. But these don’t count, in my opinion, towards any greater understanding of and knowledge about plants and their uses.

That’s not to say that the BBC (or Sir David) have completely ignored plants. In January 2022, his five episode The Green Planet series was broadcast. It was, for me however, a bit like the curate’s egg²: good in parts.

And you have to go way back to 2003 for his The Private Life of Plants series, described as a study of the growth, movement, reproduction and survival of plants.

Before that, I can only think of Geoffrey Smith‘s World of Flowers double series, broadcast on BBC2 in 1983 and 1984, and apparently attracting an audience of over five million.

Before that, I can only think of Geoffrey Smith‘s World of Flowers double series, broadcast on BBC2 in 1983 and 1984, and apparently attracting an audience of over five million.

Who said there was no appetite for programs about plants? These programs weren’t your run-of-the-mill gardening programs. No, in each program Smith highlighted the origin and development of different groups of plant species commonly grown in British gardens.

Furthermore, conservation for many relates to animals. This is something my former Birmingham colleague Brian Ford-Lloyd and I wrote back in 1986.

So what has brought about this latest concern of mine? Well, I first came across the announcement for Planet Earth III‘s imminent broadcast on the same day recently that I subscribed to a new plant-based blog: Plant Cuttings. And there, on the home page, was the blog’s goal for all to see: to reduce plant blindness.

The blog is the creation of Mr P Cuttings (aka Dr Nigel Chaffey, a former senior lecturer in botany at Bath Spa University, and a self proclaimed freelance plant science communicator), and is dedicated to all those who find fascination in plants (and how they are used by people). You can find more about the rationale for and antecedents of Plant Cuttings here. It’s a continuation of the series of articles he published in Annals of Botany, the last one, Check beneath your boots . . ., being published in 2019 (also about ‘plant blindness’).

Unfortunately, plants are often seen as boring, especially by high school students who we need to attract to the plant sciences if the discipline (in all its aspects) is to thrive. Thus this initiative by PlantingScience, a Student-Teacher-Scientist partnership in the USA that was founded in 2005 by the Botanical Society of America.

Let me wish Nigel all the best as he develops this new Plant Cuttings blog. I’m very much in accord with his goals. After all, much of my career in the plant sciences has focused on the origin of the plants that feed us, how they can preserved for posterity in genebanks, and used to increase crop productivity.

So what sparked my interests in plants and human societies?

While a high school student, I first thought I’d become a zoologist. But I saw the light and my interests turned towards plants, and I took a botany degree (combined with geography) in the late 1960s at the University of Southampton.

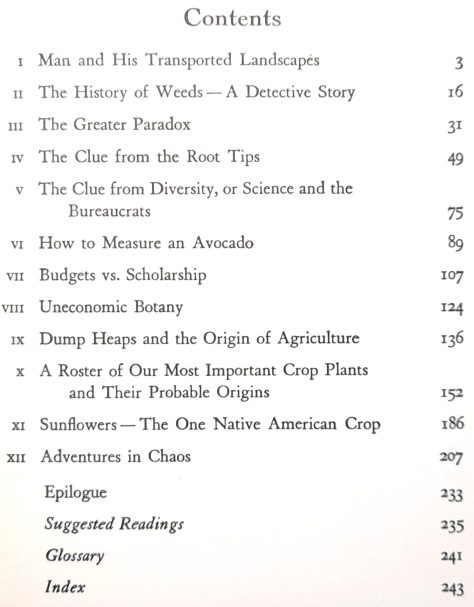

One of the books that I read was first published in 1952 (I have the 1969 reprint) by American botanist Edgar Anderson. He wrote it for readers with little technical understanding of plants. After 70 years it has stood the test of time, and I thoroughly recommend anyone who has the slightest interest of the relationships between humans and plants to delve into Plants, Man & Life.

Thus I’ve been fascinated for decades about the beginnings of agriculture and how humans domesticated wild plants, and where, and to what uses they have put the myriad of varieties that were developed. My own expertise in conservation of genetic resources has permitted me to explore the Andes of Peru to find many different varieties of potato, the foundation on which Andean civilizations such as the Incas became successful.

Collecting potatoes from a farmer in northern Peru, May 1974.

A graduate student of mine worked out the probable origin of the grasspea, a famine crop in some parts of the world. And I’ve managed the largest genebank for rice in the world (rice feeding half the world’s population every day), and with my colleagues expanded our knowledge of the relationships of cultivated rices to their wild ancestors. I directed a five year program in the mid-1990s to collect cultivated rices from many countries in Asia and Africa, especially from the Lao PDR.

These are just three examples from all the plants which societies use and depend on. So many more, and so many fascinating stories of how civilization and agriculture developed.

Just recently, on holiday in North Wales, my wife and I came across the site of about 20 hut circles on the northwest tip of Anglesey, dating back to the Iron Age, some 2500 years ago.

What is particularly fascinating for me is that there is good evidence that crops like wheat, barley, and oats among others were being cultivated there 3000 years earlier. That’s about 4500 years after these crops were first domesticated in the Near East in Turkey and along the river valleys of the Tigris and Euphrates. In the intervening years, these crops were carried across Europe by migrating peoples as they headed west until they became staples on the far west of mainland Britain. The domestication and expansion of these crops is also the story of those societies.

Plants are definitely not boring. Botany opens up a host of career opportunities. Today we need to harness the whole range of plant sciences, from molecule to field, to understand and use all the genetic diversity that is safely conserved in genebanks around the world, and backed up in many cases in the Svalbard Global Seed Vault. We now have so many more tools, particularly molecular ones, at our fingertips to study plants.

Be sure to follow Plant Cuttings to find out more about the joy of plants and their value to humankind. I trust many more generations will be proud to say they became botanists (or, at the very least, took up one of the allied plant sciences).

¹I watched the first episode of Planet Earth III on BBC IPlayer catch up. Verdict: stunning photography but boring content, seemingly a rehash of so many nature programs. All animals. However, at 97, Sir David Attenborough is a remarkable presenter.

² A curate’s egg is something described as partly bad and partly good.

To most people the word ‘conservation’ conjures up visions of lovable cuddly animals like giant pandas on the verge of extinction. Or it refers to the prevention of the mass slaughter of endangered whale species, under threat because of human’s greed or short-sightedness. Comparatively few people however, are moved to action or financial contribution by the idea of economically important plant species disappearing from the face of the earth. Precious orchids with undoubted aesthetic appeal, or the vegetation of the Amazonian rain forest, where sheer vastness cannot fail to impress, may attract deserved attention. But plant genetic resources [or plant biodiversity as a whole, I would hasten to add] make little impression on the heart even though their disappearance could herald famine on a greater scale than ever seen before, leading to ultimate world-wide disaster.

To most people the word ‘conservation’ conjures up visions of lovable cuddly animals like giant pandas on the verge of extinction. Or it refers to the prevention of the mass slaughter of endangered whale species, under threat because of human’s greed or short-sightedness. Comparatively few people however, are moved to action or financial contribution by the idea of economically important plant species disappearing from the face of the earth. Precious orchids with undoubted aesthetic appeal, or the vegetation of the Amazonian rain forest, where sheer vastness cannot fail to impress, may attract deserved attention. But plant genetic resources [or plant biodiversity as a whole, I would hasten to add] make little impression on the heart even though their disappearance could herald famine on a greater scale than ever seen before, leading to ultimate world-wide disaster. For many years, the

For many years, the